Leases

Leases

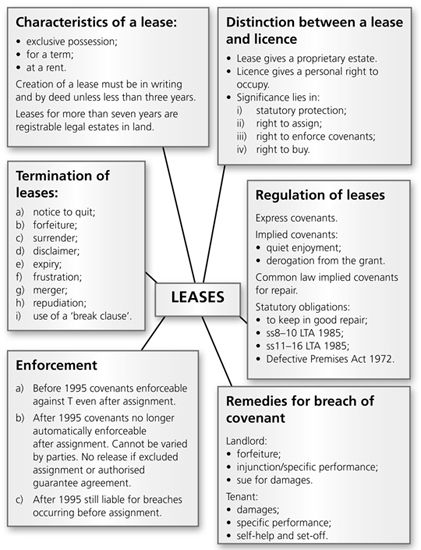

13.1 The Characteristics of a Lease

1. Under s1(1)(b) LPA 1925 the term of years absolute is a legal estate in land and is also a proprietary estate.

2. A lease or tenancy has proved difficult to define and there is no adequate statutory definition.

3. Under Street v Mountford (1985) a lease has three main identifying features:

exclusive possession of land;

exclusive possession of land;

a determinate period;

a determinate period;

rent or other consideration, although this has been doubted in recent decisions.

rent or other consideration, although this has been doubted in recent decisions.

13.1.1 Exclusive Possession

1. This means that the tenant has control over who enters the premises and can exclude everyone, including the landlord.

2. A tenant can still have exclusive possession even if he can be required to vacate the premises for a period each day (Aslan v Murphy (1990)).

3. Sole occupancy of land is not the same as exclusive possession (Westminster City Council v Clarke (1992)). The court will look at the nature of the accommodation when deciding if there is a lease. In Clarke there was no exclusive possession of a room in a council hostel for single men because residents could be required to change rooms at will.

4. A key retained so the landlord can use the premises for his own purposes will negate exclusive possession. However the retention of a key by the landlord does not necessarily mean that there is no exclusive possession if it is solely for access to carry out repairs or for emergencies (Aslan v Murphy (1990)).

5. A lodger does not enjoy exclusive possession (A-G Securities v Vaughan (1990)). Lodgings usually suggest that services are provided, e.g. the collection of rubbish or the cleaning of windows.

6. There will not be exclusive possession if premises are provided by the employer for the better performance of a job. But provision of premises by an employer unconnected with work allows the employee to claim that he/she has exclusive possession (Norris v Checksfield (1991)).

8. There may be exclusive possession even where the landlord does not have a legal estate to support a lease. (In Bruton v London & Quadrant Housing Trust (1999), the landlord had a mere licence but the landlord still had the right to create a lease in favour of the claimant.)

13.1.2 A Determinate Period

1. The maximum duration of the lease must be fixed from the start of the term.

2. Property let for uncertain periods, e.g. for the duration of the war (Lace v Chandler (1944)) will not constitute a lease.

3. A clause allowing the lease to be determined before the expiry of the full term granted will not cause it to fail as a lease.

4. Leases for lives and leases until marriage are statutorily converted into a 90 year term determinable on the death or marriage of the original lessee (s146 LPA 1925).

5. A perpetually renewable lease is converted automatically into a term of 2000 years, determinable only by the lessee.

6. A periodic tenancy can exist as a tenancy because it is regarded as running for the period of the term of tenancy and then it is renewed for a further term (Hammersmith and Fulham LBC v Monk (1992)).

7. A periodic tenancy can still exist as a tenancy even though there is no fixed term of maximum duration.

8. An example of a periodic tenancy: X grants Y a weekly tenancy – the law regards the period of the lease as one week, but renewable with the agreement of the parties at the end of every week.

13.1.3 The Obligation to Pay Rent

1. Historically, this was an essential feature of a lease and it would be implied where it was not expressly included.

2. It was held to be one of the hallmarks of a tenancy in Street v Mountford (1985).

3. Rent need not be adequate and could be in a form other than money, e.g. in kind.

4. Rent must be certain on the date for payment.

5. This has later been disputed in Ashburn Anstalt v Arnold (1989) and also in Westminster C.C. v Clarke (1992). The most recent decision on the issue (Bruton v London & Quadrant Housing Trust (2000)) upholds the principle that rent is not necessary for the creation of a tenancy, although in practice rent is usually payable.

6. A rent review clause can be included which varies the amount to be paid, but if rent can be varied arbitrarily it suggests that a licence exists (Dresden Estates v Collinson (1988)).

13.2 The Distinction Between a Lease and a Licence

1. The main differences between a lease and a licence:

a lease confers a proprietary estate, which gives the tenant an exclusive right of possession;

a lease confers a proprietary estate, which gives the tenant an exclusive right of possession;

a licence does not confer a proprietary estate, but merely gives the licensee personal permission to occupy.

a licence does not confer a proprietary estate, but merely gives the licensee personal permission to occupy.

2. The main similarities between the two are that they both confer a right to exclusive occupation of land in exchange for consideration.

3. The distinction between the two has become less marked in recent years.

13.2.1 The Significance of the Lease/Licence Distinction in Law

1. A tenant can assign his interest in land and the lease is enforceable against the original lessor.

2. If the landlord sells or transfers his interest in land, then the lease is capable of binding the transferee. A lease over seven years will be registrable by the tenant but a lease under seven years will be overriding.

3. A licensee cannot claim statutory protection under the landlord and tenant legislation, e.g. the Rent Act 1977, The Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (business tenants only), although they have some protection under the Housing Act 1985.

4. Residential tenants under long leases may have the right to purchase the freehold.

5. Tenants have the right to enforce repairing covenants in the lease. This right is unavailable to licensees (Landlord and Tenant Act 1985) (Bruton v London & Quadrant Housing Trust (1999)).

6. The Protection from Eviction Act 1977 will protect licensees as well as lessees.

13.2.2 The Parties’ Intentions

1. The tenancy is an agreement between the two parties and is subject to the usual requirements of a valid contract.

2. The courts look at the true intentions of the parties.

3. The court ignores terms used by the parties such as a ‘licence’ or a ‘tenancy’ (Street v Mountford (1985)). This was a key issue in Somma v Hazelhurst (1978) where an agreement with the hallmarks of a lease was upheld as a licence because the parties called it a licence in their agreement. In Bruton v London & Quadrant Housing Trust (2000) Lord Hoffman said ‘the fact the parties use language more appropriate to a different kind of agreement, such as a licence, is irrelevant if upon its true construction it has the identifying characteristics of a lease …’.

4. The courts distinguish between those agreements that are mere shams and those that are genuine transactions.

13.3 The Creation of a Lease

13.3.1 Formalities in the Creation of a Lease

1. Both parties must be legally competent, e.g. a minor cannot hold a legal estate in land.

2. If a minor takes a lease then that will take effect as an equitable estate in land.

3. The subject matter of the lease must be certain.

4. The formalities for the transfer of a legal estate in land must be complied with. The conveyance must be created by deed (s52(1) LPA 1925) and as defined in si LP(MP)A 1989 must be signed, witnessed and declare itself to be a deed.

5. A lease for less than three years does not require writing if it is ‘at the best rent which can be reasonably obtained without taking a fine’ and possession is immediate (a fine means a premium or lump sum of money).

6. Failure to comply with the necessary formalities results in the lease taking effect in equity only.

7. A periodic tenancy can be created orally on the basis that the period is less than three years.

8. An assignment of a term of years (even if the estate was created orally) can only be done in writing (Crago v Julian (1992)).

13.3.2 Registration of the Leasehold Estate