Justification of the Property Model for Protecting Patient Self-determination

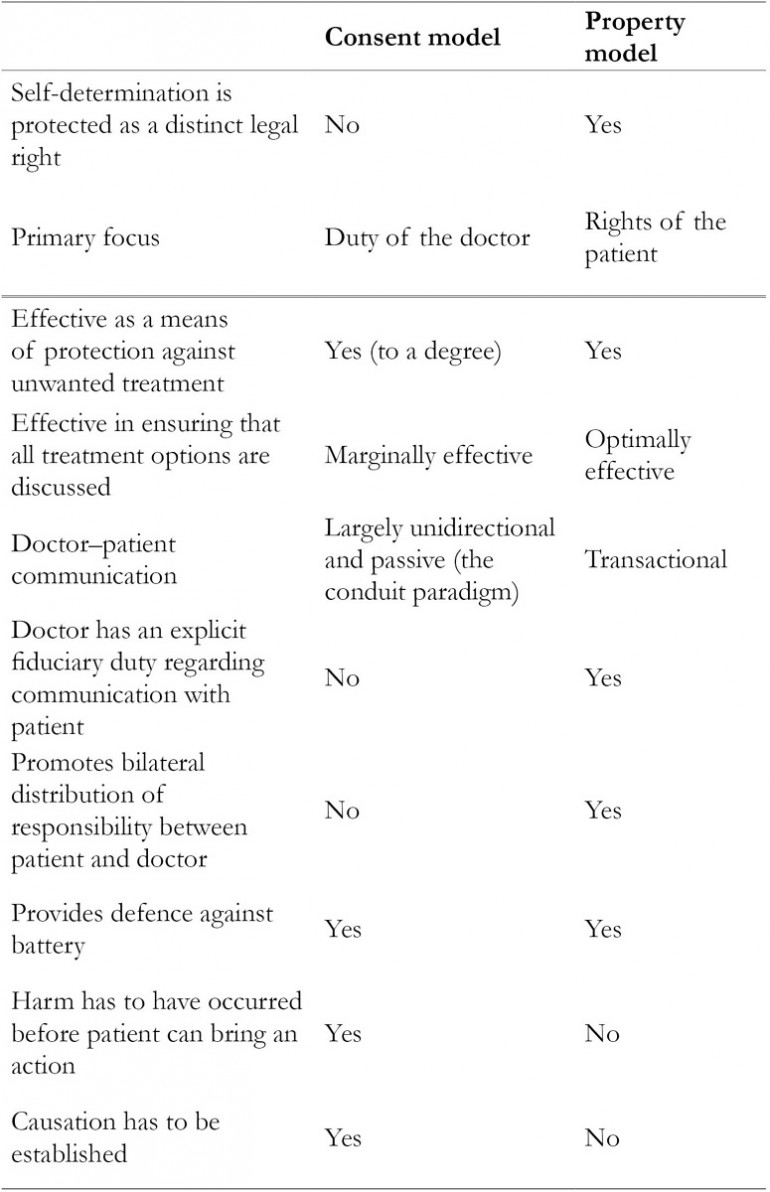

Chapter 9 Part of the imbalance between doctor and patient is due to the patient’s lack of information, and, on one view, it is the function of the law to redress the imbalance by providing patients with the ‘right’ to be given that information, or perhaps more accurately imposing a duty on doctors to provide it.1 In Chapter 3, it was shown that the mechanism by which the law purports to ‘redress the imbalance’2 and uphold the patient’s right to self-determination in medical decision-making is the law of consent. It was also shown that the consent model suffers from a number of weaknesses which limit its suitability for achieving what it is meant to achieve. One of the weaknesses is that, as applied in English courts, consent law protected the interests of a ‘homogenised’ patient rather than those of the index patient.3 By definition, self-determination is referenced to the particular patient in question, not to a hypothetical person. Accordingly, the consent model cannot truly and effectively protect the patient’s right to self-determination. Traditionally, the English courts were not particularly keen on asserting the rights of the patient in medical decision-making; rather, they deferred to medical opinion – which made it difficult for the claimant to establish breach of duty in negligence cases brought against doctors. Gradually, they became more committed to upholding patient self-determination, but their efforts in this regard were hampered by the bluntness of the tool at their disposal – the traditional consent model, which was problematic, not least because the claimant had to establish not only breach of duty but also causation. The inadequacy of this tool in the wake of contemporary judicial thinking became most glaring in Chester v. Afshar where the court resorted to jurisprudential contortions in order to protect the patient’s right to self-determination.4 Had an alternative model been available, the court could have reached the same decision through a more logical, less revisionist and less controversial analysis; one that is capable of being applied consistently in future cases and that does not entail departure from established legal principles of causation. Property analysis is presented as this alternative. The property model holds sacrosanct the patient’s right to self-determination and imposes a duty on doctors to engage proactively with patients in decision-making. This chapter seeks to identify the benefits that could flow from property analysis. With reference to landmark consent cases decided in UK courts – Sidaway,5 Chester and Montgomery – and other case law, the chapter discusses the extent to which the principles (in particular, property analysis) enunciated in this book are consistent with principles espoused by Court of Appeal and House of Lords (Supreme Court) judgments. It will be argued that the property model makes the doctor’s duty to disclose information to the patient an affirmative one, precludes limitations imposed by the objective test applied in consent cases, hybridises the strengths of ‘real consent’6 and ‘informed’ consent, limits reliance on therapeutic privilege and fits with the courts’ apparent shift towards a rights-based approach. Together, these attributes make the property model potentially better suited than the consent model to genuine protection of the patient’s right to self-determination. It must be stressed here that the property model and the consent model are not mutually exclusive models; they have a lot in common but the property model has attributes, outlined above and tabulated below, which make it potentially better suited for what the law aims to achieve. In Chapter 2, the concept of self-determination underpinning my proposition was discussed. It is this concept of self-determination that the law of consent is meant to protect. For the avoidance of doubt it is stressed again that this is different from the notion of the patient having a right to choose or demand treatment regardless of cost, medical indication or other public-interest considerations. It is simply the patient’s right to be the ultimate, informed decision-maker in respect of what should be done to his or her body. In essence, therefore, self-determination is a rights issue. It is about the rights of the patient, and the correlative duties of the doctor. In the property model, the patient’s right to self-determination is regarded as a proprietary right. Traditionally, the law and society at large have regarded proprietary rights as trumping most rights. So from the outset, adopting the property model signals the paramountcy of the patient’s right to self-determination. The stringency with which this right is protected may vary from case to case, as the right is not absolute, but there is a default presumption that this right trumps most others. The theoretical underpinnings of this proprietary right and its structure have been discussed in the last three chapters. Essentially, the patient’s bodily integrity is protected from unauthorised invasion and his/her legitimate expectation to be provided with the relevant information and opportunity to enable him/her to make an informed choice or decision regarding treatment is taken to be a proprietary right. The term ‘proprietary right’ is preferred to ‘property right’ in this book as, despite the arguments outlined in Chapter 6, ‘property’ carries the connotation of tangibility, ownership and commodification. Two essential elements of the property model are now described: the transactional approach to doctor–patient communication and the bilateral distribution of responsibility between doctor and patient. Rights are meaningless without correlative duties, and the property model compels a fiduciary duty for the doctor to communicate effectively with the patient. This communication entails not only the provision of relevant information but also the taking of reasonable steps to ensure that the patient understands the information provided and that an informed decision is made by the patient. For this to happen, the doctor–patient consultation becomes a transactional activity rather than a unidirectional flow of data across a steep informational, and sometimes social, gradient. This transactional activity and the fiduciary duty that underlies it are embedded in medical professionalism as enunciated in Chapter 8 and by medical regulatory bodies. Both judges7 and academicians8 have commented on the doctor’s duty to check that the patient understands. Morland J said: When recommending a particular type of surgery or treatment, the doctor, when warning of the risks, must take reasonable care to ensure that his explanation of the risks is intelligible to his particular patient. The doctor should use language, simple but not misleading, which the doctor perceives from what knowledge and acquaintanceship that he may have of the patient (which might be slight), will be understood by the patient so that the patient can make an informed decision as to whether or not to consent to the recommended surgery or treatment.9 (emphasis mine) In the same vein, the UK Supreme Court judges recently said: ….the doctor’s advisory role involves dialogue, the aim of which is to ensure that the patient understands the seriousness of her condition, and the anticipated benefits and risks of the proposed treatment and any reasonable alternatives, so that she is then in a position to make an informed decision. This role will only be performed effectively if the information provided is comprehensible. The doctor’s duty is not therefore fulfilled by bombarding the patient with technical information which she cannot reasonably be expected to grasp, let alone by routinely demanding her signature on a consent form.10 These observations on the duty of the doctor in respect of the patient’s understanding are not new. A quarter of a century ago, O’Neill asserted that: The onus on practitioners is to see that patients, as they actually are, understand what they can about the basics of their diagnosis and the proposed treatment, and are secure enough to refuse the treatment or to insist on changes.11 This duty tends to be overlooked in the consent model, as the model focuses on the amount of information disclosed rather than on what the patient actually understands (i.e. focus on content rather than the process of communication). If the focus shifts to ensuring that the patient understands what has been said, then clinicians will be legally obliged to pay more attention to communication skills, to the way information is provided and to checking that the patient understands the meaning and implication of the information provided – just as would normally be the case in a property transaction. Other professionals dealing with clients are expected to adopt a similar approach; for example, financial advisers are asked to ‘sense check’ their recommendations against the customer’s original objectives.12 By adopting the transactional, rather than the conduit, approach to consultation, the clinician is more likely to meet Judge Morland’s requirement to ‘take reasonable care’ to facilitate understanding. Along with the duty to take reasonable steps to check the patient’s understanding, the property model imposes an affirmative duty on the doctor to disclose tailored information to the patient. Regarding the doctor’s duty to disclose information, Lord Templeman stated: The duty of the doctor … is to provide the patient with information which will enable the patient to make a balanced judgment if the patient chooses to make a balanced judgment … The court will award damages against the doctor if the court is satisfied that the doctor blundered and that the patient was deprived of information which was necessary for the purposes I have outlined.13 In describing the requirement that the doctor be under a duty to inform his patient of the material risks inherent in the treatment, Lord Scarman (in Sidaway) sought to impose an affirmative duty on the doctor. He made this unequivocal by saying: I think that English law must recognize a duty of the doctor to warn his patient of risk inherent in the treatment he is proposing: and especially so, if the treatment be surgery.14 It appears, however, that there was no juristic basis for this affirmative duty.. Recently, however, the UK Supreme Court has affirmed that: The doctor is … under a duty to take reasonable care to ensure that the patient is aware of any material risks involved in any recommended treatment, and of any reasonable alternative or variant treatments.15 It also asserted: It is … necessary to impose legal obligations, so that even those doctors who have less skill or inclination for communication, or who are more hurried, are obliged to pause and engage in the discussion which the law requires. This may not be welcomed by some healthcare providers; but the reasoning of the House of Lords in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 was no doubt received in a similar way by the manufacturers of bottled drinks.16 To the extent that I have indicated, English law should recognise a duty of the doctor to warn his or her patient of risk inherent in the treatment which he or she is proposing, such that the patient is able to obtain redress in the event that this duty is breached, regardless of whether or not a harm has resulted from the breach. A basis for such an affirmative duty to warn the patient of risks inherent in treatment can be provided by property analysis. Property analysis, as shown in Chapters 6–8, provides a legal as well as an ethical basis for assigning rights to the patient and correlative duties to the doctor. While the doctor’s duty to disclose information should be an affirmative one, the patient also has to take some responsibility for decision-making.17 An example of how this applies is the issue of the patient’s understanding of information provided by the doctor. It has been held that the legal duty of a doctor extends to provision of adequate information but not to ensuring that the patient has understood this information.18 It must be acknowledged that imposing a duty on the doctor to ensure understanding could be both onerous and difficult to enforce. On the other hand, patient self-determination cannot be protected if there is no consideration of what the patient understands. It is submitted that one way of facilitating this is through a bilateral distribution of responsibility. The right to self-determination should carry with it obligations not only on the part of doctor but also on the part of the patient: the patient should take some responsibility for the treatment received, by communicating with the doctor, providing contextual information relevant to his/her decision-making and communicating his/her understanding to the doctor. Unfortunately (for various reasons, a discussion of which is beyond the scope of this book), this does not always happen. Section 2b of the NHS Constitution lists the responsibilities of patients.19 These include the patient’s responsibility to provide accurate information about his/her health, condition and status. The UK Supreme Court also recognised the importance of patients’ responsibilities in the context of modern thinking: [Contemporary legal and social developments] point towards…..an approach to the law which, instead of treating patients as placing themselves in the hands of their doctors (and then being prone to sue their doctors in the event of a disappointing outcome), treats them so far as possible as adults who are capable of understanding that medical treatment is uncertain of success and may involve risks, accepting responsibility for the taking of risks affecting their own lives, and living with the consequences of their choices.20 (emphasis mine) The Court also speculated that this distribution of responsibility could reduce the incidence of litigation: ….in so far as the law contributes to the incidence of litigation, an approach which results in patients being aware that the outcome of treatment is uncertain and potentially dangerous, and in their taking responsibility for the ultimate choice to undergo that treatment, may be less likely to encourage recriminations and litigation, in the event of an adverse outcome, than an approach which requires patients to rely on their doctors to determine whether a risk inherent in a particular form of treatment should be incurred.21 (emphasis mine) It is recognised that in consent discussions ‘[t]he patient can make things impossible by acting on fixed or superstitious opinions or by failing to participate responsibly in her management or its planning’.22 In Sidaway, Lord Scarman said that: a patient may well have in mind circumstances, objectives and values which he reasonably may not make known to the doctor but which may lead him to a different decision from that suggested by purely medical opinion.23 While it is the patient’s prerogative to withhold information about his/her objectives and values from the doctor, it is also reasonable that the patient should take responsibility for the consequences of doing so. The implementation of a model of doctor–patient relationship that is rooted in mutual trust – such as the property model incorporating the collaborative style of consultation adopted in Chapter 2 – will (because of enhanced trust) make it less likely for a patient to withhold from the doctor information that is relevant to his/her decision-making. Also, unless the patient discharges his/her own responsibility, the doctor will have to make an essentially arbitrary assessment of the patient’s informational needs, which is the opposite of what the principle of self-determination seeks to protect. The consent model does not create the right environment for patients to take responsibility in the decision-making process. One study found that at the point of signing a consent form, many patients are unaware that this is meant to be an exercise of their own right; they see it as an exercise to protect the doctor.24 The authors of the study state that: while medical professionals may recognise the desirability of a two-way transaction, it may not operate this way in practice if patients fail to understand that the purpose of the consent process is to respect their autonomy.25 When obligations on both sides are addressed, tension between the patient’s legitimate expectations and the doctor’s duty is eased. This is the essence of a transactional approach to medical consultation. As stated in Chapter 5, a model which takes due account of the communicative transaction leading up to the decision, rather than just focusing on the final decision, will meet the imperatives of cultural sensitivity and uphold the principle of self-determination. The emphasis on both the doctor’s duty and the patient’s responsibility manifests the property model’s primary concern: the relationship between doctor and patient. The consent model does not take full account of the bi-directional dynamics of this relationship, and has appeared to be an impediment to the relationship. The newer, nuanced conceptions of consent have not changed this. Maclean says, for example, that while Manson and O’Neill prioritise consent as communication, they do so primarily by focusing on the obligations of the health-care professional, which in turn means that attention shifts back to disclosure and truthful disclosure rather than to interaction between both parties.26 A fundamental weakness of the consent model is that its starting point is not the patient’s rights but the doctor’s duty. This is reflected in the following observation by Miller: The 1980 case of Chatterton v. Gerson seems to be the first reported opinion to hold that a doctor ‘ought to warn of what may happen by misfortune, however well the operation is done, if there is a real risk of misfortune inherent in the procedure.’ This duty to warn was derived from the physician’s general duty of care, however, rather than from the patient’s right to receive information. The court found that the physician’s duty stemmed from his professional obligation to exercise the care of a responsible doctor in similar circumstances, as set forth in the landmark case of Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee.27 (references omitted) To afford optimal protection to patient self-determination, the starting point has to be the patient’s rights. One of the features of the proposed property model is that it seeks protection of the right to self-determination as a distinct legal right. Affording patient self-determination this degree of protection would be in keeping with Lord Munby’s recent statement that rights issues ‘have to be more than what Brennan J in the High Court of Australia once memorably described as “the incantations of legal rhetoric”’.28 While recognising the importance of patient self-determination, the law has not moved to protect this as a right per se, independent of the outcome of a trespass to this right.29 Schultz argued for the legal recognition of patient self-determination as a distinct legal right.30 She drew a parallel between this argument and other legally protected rights such as the right to reputation. She further argued that legally protecting patient self-determination in this way would reduce rather than expand litigation, for it would promote better communication between doctors and patients. Twerski and Cohen suggest that self-determination could be protected by allowing patients to recover for a violation of their right to make their own informed decision.31 They state the case as follows: The legal system should protect these rights and provide significant recompense for their invasion, rather than continue its single-minded and ill-considered attention to personal injuries allegedly caused by the lack of information.32 Other authors have also called for recognition of infringement of the right to self-determination as an independent cause of action,33 and similar thoughts were expressed (albeit less forcefully) by Lord Hoffman in Chester: The remaining question is whether a special rule should be created by which doctors who fail to warn patients of risks should be made insurers against those risks. The argument for such a rule is that it vindicates the patient’s right to choose for herself. Even though the failure to warn did not cause the patient any damage, it was an affront to her personality and leaves her feeling aggrieved.34 There are two fundamental reasons why patient self-determination should be protected as a distinct right. The first one is that, as Kennedy said, it is of profound importance: … when we consider the duty of the doctor to inform his patients we are concerned with a profoundly important human right: the right to control one’s own destiny by knowing what it is that will be done by way of treatment, so that one may say no, if so minded.35 (emphasis mine) In the same vein, Lord Steyn (in Chester) said: A patient’s right to an appropriate warning from a surgeon when faced with surgery ought normatively to be regarded as an important right which must be given effective protection whenever possible.36 The second reason is that this right originates independently of any harm that the claimant may suffer. As Jackson said: we should remember why it is important to give patients information. Patients need information in order to make informed choices about their care, not in order to protect themselves against medical accidents.37 Where there has been a failure to disclose risks and alternatives, the property model entitles the claimant to a remedy once breach of the duty of care is proven, without any requirement to prove causation. In other words, the property model treats interference with the patient’s right to self-determination as a cause of action in itself, as distinct from harm to the physical well-being of the patient. Arguably, a disadvantage of recognising the patient’s right to make his/her own informed decision as an independent cause of action, not requiring any assessment of harm and its causation, is that damages awarded would be nominal.38 This should not necessarily be the case: it is logical that the compensation for infraction of this right should reflect the reason why it was deemed worthy of special protection, which is that it is ‘a profoundly important human right’.39 This point is emphasised by the use of property analysis to secure the required protection; property rhetoric is powerful. In any case, the quantum of damages is not the key issue – what matters most is the vindication of the right rather than financial recompense. The impact of a requirement to prove causation is illustrated by Lord Bingham’s judgement in Chester. Lord Bingham allowed the appeal, on the ground that the ‘but for’ test was not satisfied: ‘a claimant is not entitled to be compensated, and a defendant is not bound to compensate the claimant, for damage not caused by the negligence complained of’.40 He explains his decision not to allow the appeal by saying that the law should not hold a defendant liable where the defendant’s violation of the claimant’s right to be warned has not been ‘shown to have worsened the physical condition of the claimant’.41 In other words, he stuck to the conventional principle of causation. Unlike the majority, he did not appear prepared to bend this principle. The reason for this could not be that he did not appreciate the importance of the patient’s rights. He recognised this right but appeared to be more concerned about the quantum of damages: The patient’s right to be appropriately warned is an important right, which few doctors in the current legal and social climate would consciously or deliberately violate. I do not for my part think that the law should seek to reinforce that right by providing for the payment of potentially very large damages by a defendant whose violation of that right is not shown to have worsened the physical condition of the claimant.42 In deciding not to go with the majority Lord Bingham, like Lord Bridge, failed to make a clear distinction between the patient’s right to relevant information for informed decision-making (a right which in itself deserves protection) and the occurrence of harm of which the patient had not been warned. Lord Hoffman, who also decided for the defendant on the basis that the ‘but for’ test was not satisfied, appeared to distinguish between physical harm and infringement of personality: The remaining question is whether a special rule should be created by which doctors who fail to warn patients of risks should be made insurers against those risks. The argument for such a rule is that it vindicates the patient’s right to choose for herself. Even though the failure to warn did not cause the patient any damage, it was an affront to her personality and leaves her feeling aggrieved. I can see that there might be a case for a modest solatium in such cases.43 A focus on physical harm detracts from protection of patient self-determination as a fundamental right. If the law truly seeks to protect patient self-determination, then a remedy should be available to the patient whose right has been breached, regardless of whether he/she has suffered demonstrable harm and, in the event that there is such harm, without the burden of proving that this harm would not have occurred but for the breach. Support for the recognition of patient self-determination as a distinct legal right could be drawn from Lord Hope’s assertion that the doctor’s duty was ‘unaffected in its scope by the response which Miss Chester would have given had she been told of these risks’;44 this being the case, the doctor should be liable for any breach of the duty, regardless of what flows or results from the breach. The consent model fails in this regard, except in relation to battery where there is no requirement to prove harm – but battery is, as discussed in Chapter 3, considered an inappropriate form of action in cases relating to non-disclosure of information. Lord Hoffman’s acknowledgement that ‘there might be a case for a modest solatium’45 in cases of affront to personality, however, opens a door by means of which an alternative model could be introduced with the aim of achieving what consent fails to deliver. Recognition of the patient’s right to self-determination as a distinct right would not be unparalleled in jurisprudence; it would be akin to the protection afforded in some jurisdictions to one’s right to honour and dignity.46 In South Africa, for example, personality is a legally recognised interest protected through a modern form of the actio iniuriarum.47 The actio iniuriarum is an action for negligent behaviour that affronts the dignity, reputation or bodily integrity of the claimant.48 Rooted in Roman law, it had by the nineteenth century fallen out of favour in jurisdictions (such as Germany) where it had hitherto featured prominently, but has recently made a comeback.49 As Zimmermann put it, ‘[t]hrown out by the front door, the actio iniurarium has managed to sneak in through the back window – in the guise and under the cover of the general right of personality’.50 It was applied in the Scottish case of Stevens v. Yorkhill NHS Trust in which a mother brought an action against the doctors who, without her consent, had removed (at a post-mortem examination) and retained the brain of her baby.51 Whitty was not cited in Stevens, but had earlier argued that ‘the actio iniuriarum, in its modern form as a doctrine of rights of personality, provides a principled legal framework within which the Scottish post-mortem cases naturally, and indeed historically, belong’.52 For property analysis to establish firm roots, the courts will have to be prepared to give it a chance. Given the courts’ reluctance to recognise property rights to the human body as discussed in Chapter 7, some degree of scepticism is tenable. On the other hand, Lord Scarman’s statement in Sidaway gives a ray of hope: The common law is adaptable: it would not otherwise have survived over the centuries of its existence. The concept of negligence itself is a development of the law by the judges over the last hundred years or so … Unless statute has intervened to restrict the range of judge-made law, the common law enables the judges when faced with a situation where a right recognized by law is not adequately protected, either to extend existing principles to cover the situation or to apply an existing remedy to redress the injustice.53 This leads one to believe that the apex court left the door open for new developments – such as property analysis – but it must be borne in mind that Lord Scarman was one of the more liberal members of the court. For three decades, the seminal UK case regarding the patient’s right to be adequately informed about his or her treatment has been Sidaway, the facts of which were discussed in Chapter 3. Although the court found in favour of the defendant, all of the judges recognised that the claimant had a fundamental right to decide whether to accept or reject any treatment proposed by the doctor. What differed between them was the distance they were prepared to travel in order to protect that right. The more adventurous Lord Scarman travelled the farthest, but even he found in favour of the defendant. Lord Scarman appeared to be well ahead of his time, and was recently described as ‘one of the greatest and most socially sensitive judges of his generation’.54 He narrowed the issues at stake to these questions: Has the patient a legal right to know, and is the doctor under a legal duty to disclose, the risks inherent in the treatment which the doctor recommends? If the law recognizes the right and the obligation, is it a right to full disclosure or has the doctor a discretion as to the nature and extent of his disclosure?55 These questions and the way Lord Scarman addressed them are underpinned by rights-based thinking. He opined that the patient’s right to make his own decision ‘may be seen as a basic human right protected by the common law’56 and went on to say: If, therefore, the failure to warn a patient of the risks inherent in the operation which is recommended does constitute a failure to respect the patient’s right to make his own decision, I can see no reason in principle why, if the risk materialises and injury or damage is caused, the law should not recognize and enforce a right in the patient to compensation by way of damages.57 Lord Scarman acknowledged that in cases relating to informing the patient of the benefits, risks and alternatives of treatment, ‘the court is concerned primarily with a patient’s right’58 and that ‘[t]he doctor’s duty arises from his patient’s right’.59 Still placing the patient’s rights in pole position, he goes on to say: If one considers the scope of the doctor’s duty by beginning with the right of the patient to make his own decision whether he will or will not undergo the treatment proposed, the right to be informed of significant risk and the doctor’s corresponding duty are easy to understand: for the proper implementation of the right requires that the doctor be under a duty to inform his patient of the material risks inherent in the treatment.60 If the law accords primacy to protection of the patient’s rights, and in particular the patient’s right to adequate information and involvement in decision-making, then property analysis is advantageous in so far as it protects the patient’s rights more stringently than the consent model does. Lord Scarman’s view of the patient’s right to make his or her own decision as a basic human right is consistent with the case made above for this right to be protected as a distinct legal interest under the property model. It is also encompassed in the concept, enunciated in Chapter 8, of property rights in the patient’s expectation of sufficient disclosure of information during a medical consultation. The other judges did not adopt the rights-based approach of Lord Scarman. There are a number of reasons for this, as reflected in the judgments. One reason was the then prevalent deference to the medical profession. The other was the prevailing social norm which did not prize individual self-determination in the way that contemporary society does. Lord Diplock held that the Bolam test should be applied.61 In this regard, and in the tone of his judgment, he was diametrically opposite to Lord Scarman. In his view, the doctor’s duty of care had always been and should continue to be ‘treated as single comprehensive duty covering all the ways in which a doctor is called upon to exercise his skill and judgment’,62 and the entirety of this duty of care is subject to the Bolam test. He did not see any reason to distinguish the duty to inform the patient of risks from the more technical aspects of care, and pointed out that even the Bolam case itself included a claim of failure to warn: This general duty is not subject to dissection into a number of component parts to which different criteria of what satisfy the duty of care apply, such as diagnosis, treatment, advice (including warning of any risks of something going wrong however skilfully the treatment advised is carried out). The Bolam case itself embraced failure to advise the patient of the risk involved in the electric shock treatment as one of the allegations of negligence against the surgeon.63 As the duty to warn is not, in Lord Diplock’s view, separable from diagnosis and treatment, expert evidence in this regard should be treated the same way – that is, the professional standard applied: To decide what risks the existence of which a patient should be voluntarily warned and the terms in which such warning, if any, should be given, having regard to the effect that the warning may have, is as much an exercise of professional skill and judgment as any other part of the doctor’s comprehensive duty of care to the individual patient, and expert medical evidence should be treated in just the same way. The Bolam test should be applied.64 This view that the patient should be told not what he/she expects to be told but what the medical profession feel he/she should be told was subsequently followed by the Court of Appeal in two cases.65 In Gold v. Haringey Health Authority the claimant became pregnant and had her fourth child, despite having been sterilised in 1979 at the defendants’ hospital.66 She brought an action in negligence, and alleged that she was not warned of the risk of failure of the sterilisation. The court was told that a substantial body of medical opinion in 1979 would not have informed the patient of the possibility that a sterilisation operation could fail. In spite of this professional opinion, the court found for the claimant. On appeal, the Court of Appeal found in favour of the defendants. This position was, however, strongly criticised by academic commentators who have argued, with good reason, that the duty to inform patients of benefits, risks and alternatives should be separated from the more technical aspects of care such as details of diagnosis and treatment.67 On the other hand, there is some logic in Lord Diplock’s view that the provision of information is part of the duty of care, just as is making a diagnosis or providing safe care. While it is accepted that there is a difference between the strictly technical aspects of care and the discussion of risks, benefits and alternatives, the divergence between the two when it comes to the law (whereby one test is applied to a part of the duty of care but a different test is applied to another component of that duty) only serves to underscore the inadequacy of the consent model – discussion of risks, benefits and alternatives had to be extricated from the duty of care in order for consent to work as a legal means of protecting patient self-determination (otherwise the Bolam test applied). Potentially, this can be avoided by exploring the option of a property model. With the property model, the question of whether Bolam applies to information-giving does not arise; once the proprietary right is breached, the patient is entitled to redress. It could be argued that the shift away from the Bolam test in determining disclosure standards actually started with Sidaway itself. Although Lord Scarman was alone in taking the view that the patient’s right to information trumped professional opinion, three of the other four judges – Lord Bridge, Lord Keith and Lord Templeman – did take small but significant steps in this direction, by advocating a modified Bolam test. Lord Bridge, with whose judgment Lord Keith agreed, invoked the ‘realities of the doctor/patient relationship’ as one reason why a doctrine enforcing the patient’s right to self-determination would be ‘quite impracticable in application’.68

Justification of the Property Model for Protecting Patient Self-determination

The Property Approach to Protecting Self-determination

Effective Communication

The Doctor’s Duty to Disclose Information to the Patient: An Affirmative Duty

Bilateral Distribution of Responsibility

Recognition of Patient Self-determination as a Distinct Legal Right

In the Absence of Physical Harm, the Patient may be Left with Nothing

Personality as a Legally Recognised Interest

Adoption of Property Analysis: Receptivity of the Courts to New Developments

From Sidaway to Chester: The Appellate Courts in Transition

Lord Scarman’s Rights-based Position

Deference to the Medical Profession

The First Steps of Departure from Bolam