Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence

1.1.1 Reasons for Study

1. The main purpose of studying jurisprudence or legal theory is to provide a framework within which students can locate and reflect upon all aspects of their study of law, including its:

(a) origins, history and development

(b) intellectual foundations and justifications

(c) relationship to other academic and practical disciplines, such as:

philosophy

philosophy

social theory

social theory

criminology

criminology

politics

politics

economics.

economics.

(d) role in the interpretation of the ‘black letter’ law subjects (i.e. principles or rules of law which are generally known and free from doubt or dispute) that constitute the bulk of most A-level syllabi and law degrees, such as contract, tort, and crime, studied within a particular (e.g. English or French) legal system.

2. Jurisprudence therefore transcends the boundaries between the various municipal (i.e. national) laws, yet still needs to be distinguished from international law, which may be:

(a) private international law, or conflict of laws, where problems need to be resolved on private matters such as divorce or contract involving different legal jurisdictions, e.g. England and Ghana

(b) public international law, involving issues arising between sovereign states.

3. It can be studied at introductory, intermediate or advanced level, depending on whether the student needs to gain a:

(a) clear bird’s eye view

(b) broad grasp of historical and intellectual trends (e.g. the relationship of natural law to legal positivism)

(c) more detailed grasp of particular concepts (e.g. realism, sociology of law, rights or economic law calculus, or the idea of justice). For all levels this book provides a useful reference and revision tool.

4. This first chapter outlines many of the concepts and ideas that constitute legal theory, which are amplified and explained further in subsequent chapters. Students should find section 1.2 defining jurisprudential theories and language particularly useful.

1.1.2 Meaning of ‘Jurisprudence’

1. The word ‘jurisprudence’ is derived from the Latin juris prudentia, generally meaning knowledge or study of the (social) science of law, although it may mean other things in particular contexts, e.g.:

(a) case law

(b) laws of a particular jurisdiction, e.g. French law

(c) particular ‘families’ of law, e.g. the civil law tradition, derived from Roman law, as compared with the common law tradition descended from English common law.

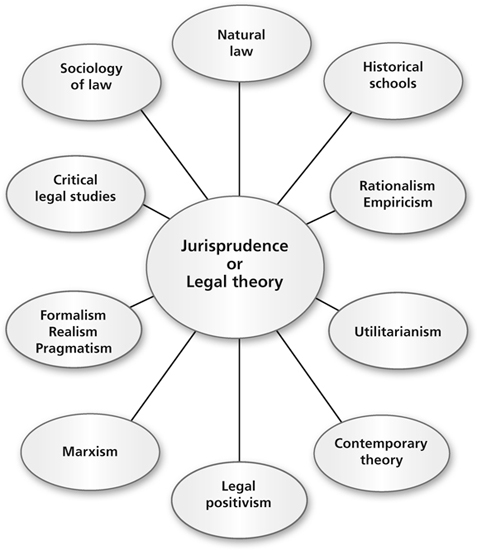

2. However, there are many differing approaches to the theory of law, and although these may often be categorised as indicated below, there is also much blurring of the lines between them, and in some cases hardly any lines to blur.

3. Thus, although no one would be likely to argue that Kelsen (chapter 4) was not a legal positivist or Aquinas (chapter 2) a naturalist, many writers cannot be so neatly pigeon-holed, e.g.:

Fuller (chapter 2) occupies a more ambiguous naturalist position

Fuller (chapter 2) occupies a more ambiguous naturalist position

Hart (chapter 5) adopts a more qualified or perhaps advanced positivist stance

Hart (chapter 5) adopts a more qualified or perhaps advanced positivist stance

Dworkin (chapter 10) has formulated what has been described as a ‘third way’ between natural law and legal positivism

Dworkin (chapter 10) has formulated what has been described as a ‘third way’ between natural law and legal positivism

some writers adopt a radical political stance that is not necessarily clearly rooted within traditional boundaries, e.g. Marxists or sociologists of law

some writers adopt a radical political stance that is not necessarily clearly rooted within traditional boundaries, e.g. Marxists or sociologists of law

others would not see themselves as subscribing to any traditional category, but within their own broad classification (e.g. critical legal studies, realism or historicism) can be just as difficult to pin down

others would not see themselves as subscribing to any traditional category, but within their own broad classification (e.g. critical legal studies, realism or historicism) can be just as difficult to pin down

which ever legal philosophers are being studied, they are usually characterised by subtlety and complexity of language.

which ever legal philosophers are being studied, they are usually characterised by subtlety and complexity of language.

4. Nevertheless, some attempt at classification is needed in order to bring both wood and trees into focus, so after outlining the main categories and general definitions, more detailed consideration is given to some of the principal legal philosophers and their ideas and writings on legal theory.

1. There are a number of broad ways of approaching jurisprudence, so legal theory may be addressed by studying (see section 1.2 for a table of definitions):

(a) analytical and normative jurisprudence

(b) doctrinal theory

(c) policy analysis

(d) comparative explanations and classification

(e) criticism of distinctive bodies of law

(f) comparisons of law with other categories of knowledge

(g) critical theories of law such as race or gender (chapter 11).

2. A variant to such methodologies is to examine legal philosophy by reference to social science and humanity disciplines, some of the more usual including:

(a) history

(b) (moral) philosophy

(c) political science or economy

(d) anthropology and culture.

3. This may be refined to the study of more specific allied conceptual subjects such as:

(a) justice

(b) punishment

(c) rights

(d) obligations

(e) equity

(f) legal personality.

4. The objective of much legal philosophical writing is to provide answers to questions such as:

(a) what is law, and what is its purpose?

(b) how does a legal system operate?

(c) are there sufficient common factors that can be identified to produce a general theory?

(d) is law something that can stand alone, or does it need to be welded to concepts such as justice or morality, or a vaguer notion of the ‘spirit of the people’ (volksgeist), in order to be valid?

(e) stated slightly differently – is there, or should there be, any necessary nexus or connection between law (or a legal system), and subjective or cultural concepts such as rights, obligations or justice? (The important question of the difference between ‘is’ and ‘ought’ is dealt with in the following section.)

5. When legal philosophers commence their studies and write about their theories, the process is often referred to as that particular writer’s ‘project’, thus:

(a) in a study of the relationship between globalisation and legal theory comprising a decade of research and essays, William Twining refers to it as his project, his purpose being to explain the phenomena he discovers and to analyse them in context

(b) Aquinas’s ‘project’ (although in his time he would not have called it such) was to explain the relationship between God’s law and human law, whilst Marx’s was to show that law is historically inevitable and secular.

1.1.4 ‘Is’ and ‘Ought’

1. A crucial distinction that always needs to be borne in mind in jurisprudential discussion is the question of ‘is’ and ‘ought’:

(a) some legal philosophers concern themselves with analysis of what a particular subject is, which involves objective description, explanation and discussion

(b) in other cases the writer will be evaluating the aims and objectives he or she considers a system ought to achieve, inevitably involving consideration of subjective criteria.

2. The impossibility of deriving an ‘is’ conclusion from ‘ought’ premises was highlighted by Hume (section 3.1.4) who pointed out that:

(a) it is not logical to reach conclusions about what ought to happen from facts about what actually is

(b) the consequence of this is that normative or behavioural conclusions cannot follow from statements of fact (see section 3.1.4).

3. This can be demonstrated by a syllogism (see the table in section 1.2 and section 6.3.8 for the definition), the valid form of which is as follows:

(a) all women are human

(b) Ruth is a woman

(c) therefore, Ruth is human.

4. Ethical non-cognitivism, however, leads to a fallacious or false syllogism, e.g.:

(b) Brian is a pig

(c) therefore, Brian ought to have trotters.

5. Although it may be considered very likely that Brian will actually have trotters, it is not valid to conclude that he ought to have them, which is the fallacy or false argument identified by Hume.

6. It should be noted that from an academic point of view it is not conclusively right or wrong, inferior or superior, to write about law as it is or as the writer considers it ought to be, but it is important that the distinction should always be clearly drawn.

7. From the philosophical viewpoint, however, natural lawyers argue that you cannot have a proper legal system that is devoid of religious or moral content, whilst the purer legal positivists would say that law and morals are, or should be, kept distinct and separate.

1.1.5 Natural Law

1. Natural law is the theory that law can only be understood by requiring that extraneous or non-legal matters should be taken into account in determining its meaning and legitimacy.

2. These imported ideas are generally moral elements, and more specifically would link natural law to such considerations as:

(a) religion

(b) morals

(c) rights

(d) reason

(e) justice

(f) conscience.

3. By implication, natural law incorporates the overlap thesis, the ‘overlap’ being the extent to which law and morality should be considered together and treated as part and parcel of each other, although opinion differs markedly as to the extent to which and the ways in which this might occur.

4. At the more intense end of the spectrum are located writers such as Aquinas and Blackstone, who in effect argue (although from different religious viewpoints) that law cannot be law if it does not accord with their notion of what God requires law to be, which inevitably involves questions of external imposition and faith.

6. Natural law may play an unexpected role in the formation of individual legal systems, e.g. canon or Church law was formative as one of the strands that went into (later) common law.

7. Complete legal traditions (as opposed to separate individual state legal systems) may in this sense have a natural law foundation, such as the:

(a) Islamic Shari’a

(b) Jewish Talmud

(c) Hindu laws of Indian origin.

8. Others, adopting a less stringent overlap basis, would only suggest that there should be some minimum moral element in a legal system if it is to carry authority for those who comprise its subjects, thus implying a secular link between law and morality that need not be founded on religion.

9. Some of the more obvious difficulties concerning natural law are that: