Jurisdictional Challenges

JURISDICTIONAL CHALLENGES

9.01 | |

Expanding the Adjudicator’s Jurisdiction During the Adjudication | 9.09 |

(3) When Can a Claim Be Withdrawn or an Adjudication Restarted? |

(1), General Principles

Source and Nature of the Adjudicator’s Jurisdiction

9.01 In the context of adjudication, to refer to the jurisdiction of the adjudicator is to refer to the power of the adjudicator or the scope of the adjudicator’s authority. Any decision reached by an adjudicator who had no jurisdiction to make that decision will not be enforceable. The adjudicator may lack jurisdiction to make any decision at all or, for a variety of reasons that are discussed below, may lack the jurisdiction to make a particular decision. Equally, the adjudicator may have jurisdiction in relation to part of the decision but not in relation to another part. In the latter case if the decision is severable then it may be that only the part of the decision that was made without jurisdiction will be unenforceable.1

9.02 Unlike the courts, an adjudicator has no inherent power to make any binding determination in respect of the rights or obligations of any party. An adjudicator gains such power by virtue of his appointment to adjudicate an identified dispute and the referral of that dispute for determination, but only if the party purporting to appoint the adjudicator is entitled to seek the appointment of an adjudicator to determine that dispute.

9.03 A party has no inherent entitlement to appoint an adjudicator to determine a dispute; any such entitlement only arises by virtue of the appointing party’s contractual arrangements with the party with whom it is in dispute. The entitlement to appoint an adjudicator may arise as the result of an express provision in the contract, or be implied by the operation of s. 108 of the Act if the contract is a ‘construction contract’ within the meaning of s.104.2 The right to appoint an adjudicator may also arise as a result of an ad hoc agreement between parties to resolve that dispute by adjudication.3

9.04 The first step in identifying the jurisdiction of an adjudicator is therefore an examination of the contract between the parties to the dispute. If there is no express adjudication provision and the requirements of s. 104 of the Act are not satisfied then, in the absence of an ad hoc agreement to adjudicate, any adjudicator appointed will have no jurisdiction.

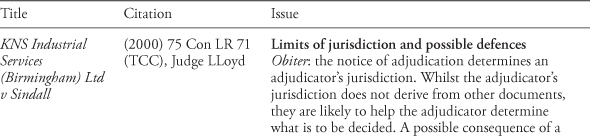

9.05 The second step is to identify the limits of the adjudicator’s jurisdiction, in particular the matters on which the adjudicator has the power to reach a decision and the relief which may be granted. The scope of the adjudicator’s jurisdiction is initially circumscribed by the content of the notice of adjudication.4 In particular the adjudicator may only determine the dispute identified in that notice and may only award the particular relief requested in that notice.5

9.06 It is important to note that, unlike natural justice challenges, if the excess of jurisdiction is made out, it is irrelevant whether or not the other party has suffered prejudice.6

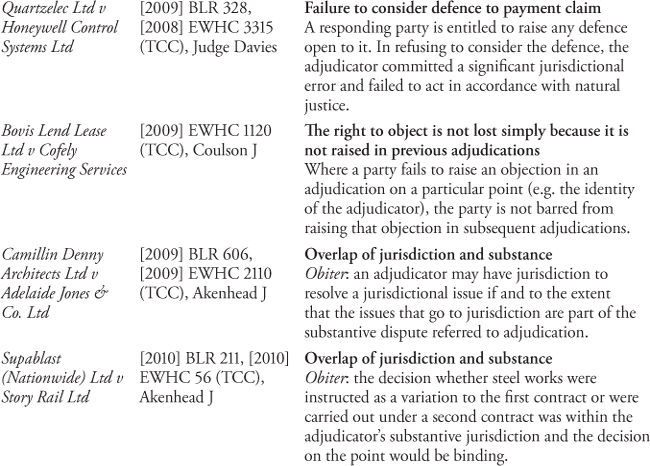

Jurisdiction to Consider any Available Defences Raised

9.07 It is now well settled that the responding party is entitled to raise any defence that is a proper defence in law to the claim being made and the adjudicator is required to consider all defences properly raised.7 It is irrelevant that the circumstances giving rise to the defence are not set out in the adjudication notice or were not raised or ‘in dispute’ prior to the reference to adjudication. It would be ‘absurd’ if the referring party could, through ‘some devious bit of drafting, put beyond the scope of the adjudication’ the responding party’s otherwise legitimate defence to the claim.8 The failure of an adjudicator to consider a valid defence is usually the result of the adjudicator misunderstanding the scope of his or her jurisdiction which may result in a breach of natural justice.9 This topic is discussed in more detail in Chapter 10 at 10.36–10.53.

9.08 The adjudicator’s jurisdiction may therefore be extended as a result of any matters raised by the responding party that necessarily require the adjudicator to determine those matters. For example, a contractor’s notice may be limited to a claim for payment of outstanding sums; that claim may be met with a set-off for the cost of defects or liquidated damages. The adjudicator has jurisdiction to deal with the matters raised in defence,10 even though there was no reference to those defences in the notice of adjudication.11

Expanding the Adjudicator’s Jurisdiction During the Adjudication

9.09 It is also possible for the parties to extend the adjudicator’s jurisdiction by express agreement in the course of the adjudication.

9.10 The adjudicator has no jurisdiction until the dispute has been validly referred.12 Before that time the adjudicator has no power to decide the dispute even though he has been appointed.

Adjudicator’s Investigation of Jurisdiction

9.11 A responding party will on occasion seek to prevent an adjudication proceeding by identifying jurisdictional issues at the outset in the hope that the adjudicator will resign due to not having jurisdiction. Whilst there is no obligation on an adjudicator to enquire into his own jurisdiction13 it may assist the parties if the adjudicator does so to prevent costs being wasted on the adjudication, only for the referring party to discover that it has an unenforceable decision.

9.12 However, unless the adjudication agreement provides14 or the parties agree otherwise, any conclusion the adjudicator reaches in relation to his or her own jurisdiction will not bind the parties. The responding party will therefore be entitled, subject to the question of reservation of rights discussed below, to raise the jurisdictional objection in the courts, either during the adjudication (through a Part 8 application)15 or in defence of enforcement proceedings. However, one exception to this principle was identified in Air Design (Kent) Ltd v Deerglen (Jersey) Ltd (2008)16 where it was found that an adjudicator’s decision on a matter that went to his jurisdiction was binding on the parties where the adjudicator was also required to answer the same question to determine the substantive dispute he had been asked to decide.

9.13 Otherwise, there are three ways in which an adjudicator’s decision on jurisdiction will bind the parties:

1. If the adjudication rules provide that such decisions are binding, then even if the adjudicator’s decision on jurisdiction was wrong in fact or law it will not provide a basis for resisting enforcement.

2. A party may not raise a jurisdictional challenge if, by its communications or conduct, that party conferred power on the adjudicator to make a decision as to jurisdiction.

3. After having raised a jurisdictional objection, or if a potential jurisdictional objection was or should have been reasonably apparent in the course of the adjudication but was not raised, then if the party continues to participate in the adjudication it will only be able to rely on the objection when resisting enforcement if it clearly stated that it reserved its rights to raise the objection later and that its participation in the adjudication was under protest.

Reservation of Rights

9.14 Parties to adjudications must be careful not to inadvertently bestow jurisdiction upon an adjudicator. This may occur when a dispute or an issue is referred to the adjudicator over which he or she does not have jurisdiction, but no adequate objection is taken to it being decided by the adjudicator.17 If a party wants to raise the jurisdictional objection at a later date it may be held to have acquiesced in the adjudicator deciding the point, or to have waived its right to object to an increase in jurisdiction or a particular procedural course. The best way to avoid losing such rights of challenge is via an adequate reservation of rights. A reservation of rights may be either general (e.g. ‘the responding party reserves the right to raise any jurisdictional issues in due course whether previously raised or not’) or specific. Whilst a general reservation of rights is undesirable, it is nevertheless effective.18 However, it is important that any objection and reservation of rights (general or specific) is expressly and consistently maintained throughout the adjudication if a party is to be able to rely on the objection(s) as a challenge to enforcement. If a responding party initially raises both specific and general challenges to the jurisdiction, but later only refers to the specific challenges, it may well be found to have abandoned any general objection and only be permitted to rely on the specific objections that had been maintained.19 Similarly, if a responding party only raises a specific ground that proves unsuccessful, it cannot raise different grounds of objection when seeking to resist enforcement.20

9.15 In order to avoid these difficulties when seeking to resist enforcement on jurisdictional grounds it is suggested that the following steps are taken:

1. Make and maintain a general reservation of rights at each stage of the adjudication and on each occasion that a specific challenge is raised or repeated.

2. Any specific jurisdictional challenge that is identified during the adjudication should be raised with the adjudicator and the referring party.

3. Where a specific challenge is made, the party should expressly state that in making the challenge it does not confer on the adjudicator jurisdiction to make a binding jurisdictional determination and that it reserves its right to raise the specific challenge in any enforcement proceedings that may follow.

4. Maintain any specific objection and reservation of rights at each stage of the adjudication.

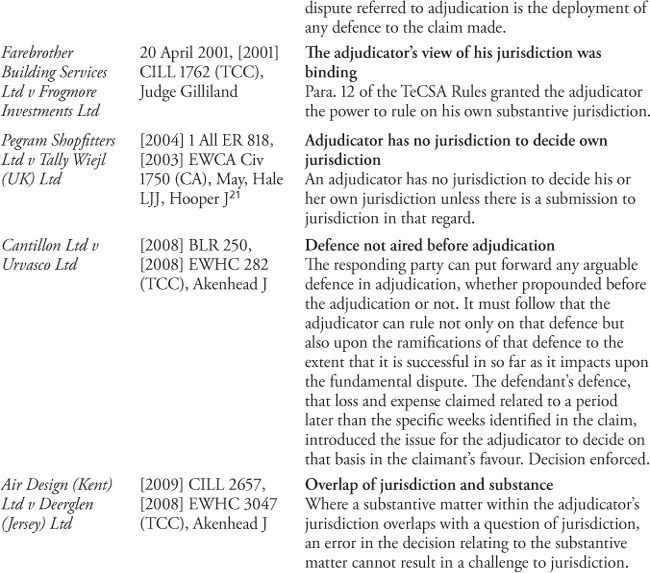

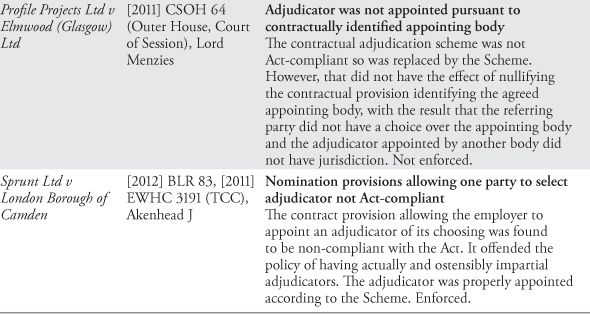

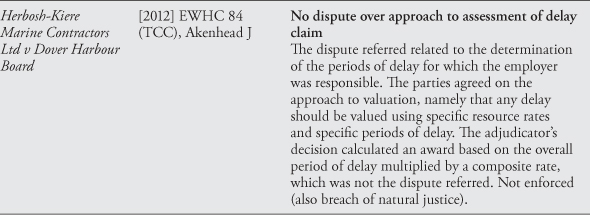

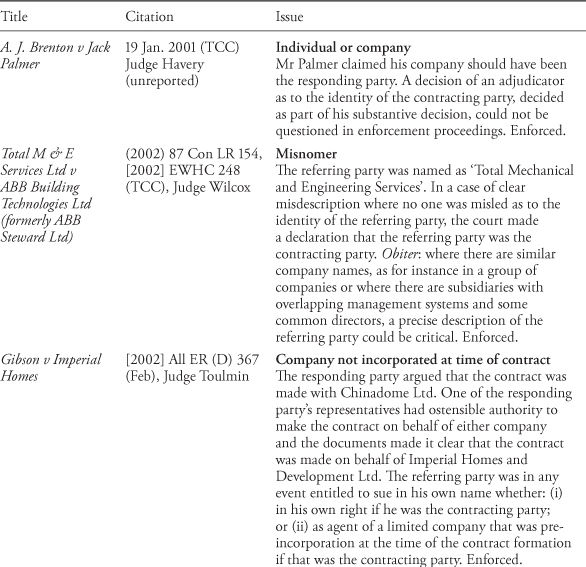

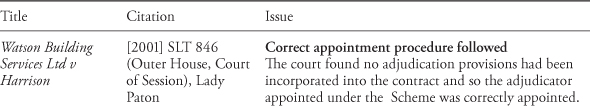

Table 9.1 Table of Cases: General Principles

(2) Matters Giving Rise to Jurisdictional Challenge

9.16 In some cases a jurisdictional issue arises because there was no jurisdiction at the outset, such as where there is no right to adjudicate because the contract is outside the ambit of the Act. Equally, where the matter referred has not crystallized into a ‘dispute’ there will be no jurisdiction to adjudicate upon it. Jurisdictional challenges that fall into this category are considered at 9.18–9.25 below.

9.17 In other situations the jurisdiction issue arises because of something that happens during the adjudication. This is the case where there are errors in the appointment of the adjudicator, where the referral is served outside the strict time limits or where the decision is late. Such situations may result in the adjudicator proceeding with the adjudication when he has no power to do so or making a decision out of time which he has no power to do. This category also includes errors made in the decision itself. Whilst the majority of errors of fact and/or law do not affect the enforceability of an adjudicator’s decision,22 there are certain errors which the courts have deemed are such that ‘they cannot be permitted to stand’23 or that go to the ‘heart’ of the adjudicator’s jurisdiction.24 So, if the adjudicator decides the wrong question, instead of the one actually referred, the resulting decision will be one made without jurisdiction and so unenforceable. Furthermore a procedural mistake by the adjudicator can result in the making of a decision that he or she is not empowered to make, such as making the decision out of time or revising the decision after it is issued in an unauthorized manner.25 Such decisions made without jurisdiction will not be enforceable and will be a nullity.26

No Jurisdiction at the Outset

Not a Construction Contract in Writing

9.18 Where reliance is placed on the Act to establish the initial threshold right to adjudicate, an adjudicator will not have jurisdiction if the requirements of the Act are not met. Consequently, challenges have been made on the basis that the contract in question is not a construction contract within the meaning of ss. 104–6 or is not an agreement in writing within the meaning of s. 107. The reader is referred to Chapters 1 and 2 for a detailed consideration of the relevant principles. However, it should be noted that courts generally adopt a robust approach to challenges based on there being no contract in writing.27

Not a Party

9.19 The responding party may contend that the adjudication was brought by or against the wrong party, with the result that one of the parties to the adjudication was not a party to the underlying contract. Pursuant to s. 108 of the Act, the adjudicator is only empowered to decide disputes arising under the construction contract and that means between the parties to that contract. This is clear from the wording of the Act which says that ‘A party to a construction contract has the right to refer a dispute’.28 There is no jurisdiction to decide a dispute between different parties unless that jurisdiction is otherwise conferred on the adjudicator.

9.20 Such cases turn on the evidence of who the contracting parties were. If that is a question that cannot be decided either way on a summary basis then at the enforcement hearing directions will be given for a full trial of that question.29 If the adjudication is started against a party that is ‘plainly wrong’ then the Court of Appeal has confirmed that the decision will not be enforced.30 However, as can be seen from Table 9.2 below, the majority of decisions have been enforced, with the courts applying the principles developed in relation to arbitration, so that where the party has simply been misnamed in the adjudication and there has been no confusion as to who the parties to the adjudication were, then a ‘wrong party’ challenge will fail. See further at 3.20.

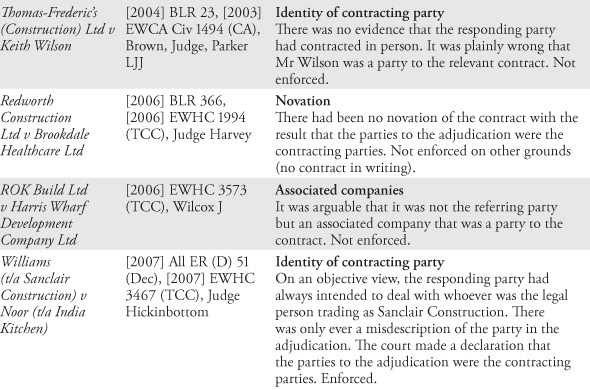

Table 9.2 Table of Cases: Not a Party (shaded entries indicate a successful challenge to enforcement)

No Dispute Crystallized

9.21 To invoke the right to adjudicate under s. 108 of the Act there must be a ‘dispute’ which is capable of being referred to adjudication. An adjudicator has no jurisdiction to determine a claim that has not yet crystallized into a ‘dispute’ unless that power is otherwise conferred.32 Enforcement of a decision may be challenged on the grounds that the matter decided, or part of it, was referred prematurely and the decision was made without jurisdiction. Although once a popular ground of challenge, the guidance given by the courts over the years has narrowed the circumstances within which absence of a dispute may be argued and challenges on this basis are now rarely successful. For a full discussion of this topic see Chapter 3 at 3.29–3.38. Equally there is no jurisdiction to adjudicate a dispute that has previously been compromised by the parties.

More than One Dispute Referred

9.22 As discussed in Chapter 3 at 3.49–3.52, the Act permits the referral of a single dispute to adjudication, although the Scheme for Construction Contracts (the Scheme) says the parties are free to agree to refer more than one dispute as long as both parties consent. Absent specific agreement to confer more than one dispute33 the decision may be challenged on the basis that more than one dispute was referred. To avoid this danger, the adjudication notice should be worded so that what is being referred is a single dispute. Consistent with the courts’ general approach of supporting the intention of Parliament by enforcing adjudication decisions wherever possible, the courts have given a broad interpretation to what comprises a single dispute and have usually construed adjudication notices as containing one dispute even though a number of different issues, or component parts of that dispute, are identified in the notice. Where more than one dispute is decided, it may be possible to sever the decision and enforce only the part made with jurisdiction. The subject of severance is discussed in Chapter 7 at 7.73–7.81.

Dispute Does Not Arise under the Contract

9.23 The wording of s. 108(1) of the Act is clear: it permits the referral to adjudication of disputes ‘arising under the contract’. The Scheme includes the same wording. It is therefore legitimate to challenge enforcement of a decision on the ground that the dispute decided did not ‘arise under’ the contract. As to the meaning of this expression and a discussion of cases in which it has been considered, see Chapter 3 at 3.10–3.14. It has also been held that there is no jurisdiction for an adjudicator to decide a dispute which concerns the taking of a single account as anticipated by r. 4.90 of the Insolvency Rules.34

Dispute under Multiple Contracts or Side Agreements

9.24 Where the dispute decided by an adjudicator arose under more than one contract the decision may be vulnerable to a jurisdictional challenge. Equally if the dispute arises wholly or in part under a side agreement it may not be a dispute that arises under the contract, which contains the adjudication agreement. This subject is discussed in Chapter 3 at 3.15–3.19.

Dispute Decided in Previous Adjudication

9.25 An adjudicator’s decision on a dispute is binding until finally determined in legal or arbitration proceedings or by agreement of the parties.35 The effect of this is to prevent successive adjudications on the same or substantially the same dispute. Thus an adjudicator has no jurisdiction to determine a dispute that has previously been decided in a different adjudication (whether by the same or a different adjudicator). This is often referred to as the rule against ‘double jeopardy’ and is discussed in Chapter 6 at 6.63–6.69.

Jurisdiction Issues Arising During Adjudication

9.26 In general, as discussed in Chapter 10, procedural errors in a validly constituted adjudication will not result in an unenforceable decision. However, certain procedural errors have been found to deprive the adjudicator of jurisdiction. In particular, an adjudicator will only have jurisdiction to decide the dispute referred if the adjudicator has been properly appointed in accordance with either any express adjudication rules or the Scheme, the dispute has been properly referred within the relevant time limits, and the decision has been provided in accordance with the applicable rules. Each of these aspects is considered in the sections below.

Errors in Appointment of Adjudicator

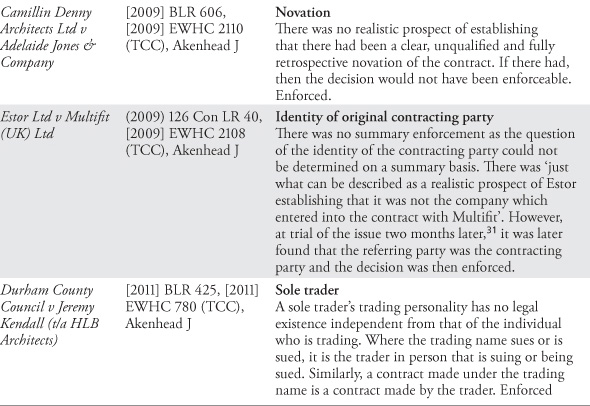

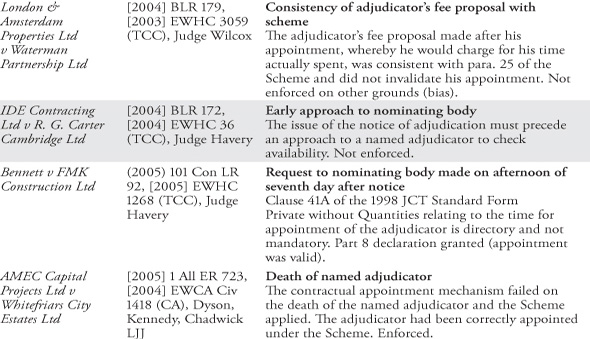

9.27 If an adjudicator has been appointed other than in accordance with an express contractual provision (if such exists), or the Scheme, then the appointment will be invalid and the adjudicator will have no jurisdiction. Each case will turn on its own particular facts, but as can be seen from the case summaries in Table 9.3, appointments have been found to be invalid as a result of the referring party applying to the wrong nominating body36 or an adjudicator being appointed who is not the named adjudicator.37

9.28 The timing of the request for appointment may also be critical. Under the Scheme, a request to a named adjudicator or nominating body is to be made ‘following the giving of a notice of adjudication…’.38 In both IDE Contracting v R. G. Carter Cambridge Ltd (2004)39 and Vision Homes Ltd v Lancsville Construction Ltd (2009),40 that Scheme provision was found to be strict, so that an approach to a nominating body or a named adjudicator (even to check availability), cannot be made prior to the issue of the notice of adjudication, however close in time the notice may have followed. Whether the same is true under a contractual appointment provision will turn on the interpretation of the contract in question. For example, it is not essential under the JCT adjudication provisions that the notice of adjudication is issued before a request is made to the nominating body.41

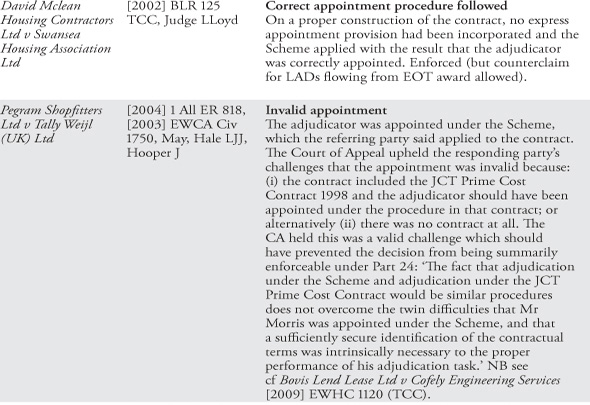

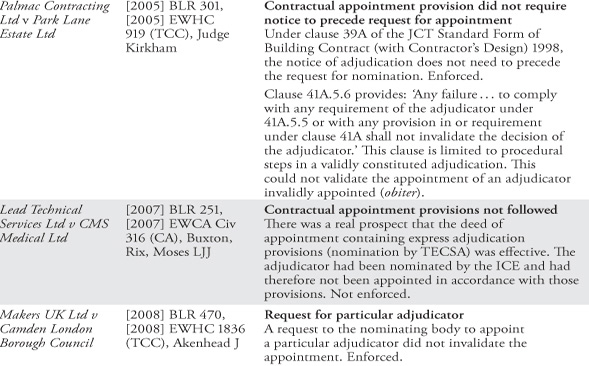

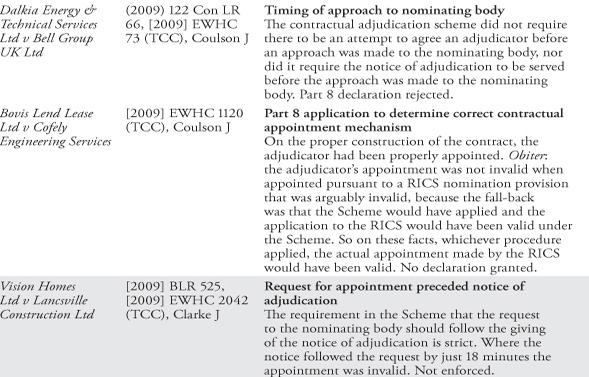

Table 9.3 Table of Cases: Failure in Appointment (shaded entries indicate a successful challenge based on appointment failure)

Late Service of Referral

9.29 Section 108(2)(b) of the Act requires that any construction contract:

Shall provide a timetable with the object of securing the appointment of the adjudicator and referral of the dispute to him within 7 days of such notice.

9.30 Paragraph 7 of the Scheme provides that:

(1) … the referring party shall, not later than seven days from the date of the notice of adjudication, refer the dispute in writing (the ‘referral notice’) to the adjudicator.

(2) A referral notice shall be accompanied by copies of, or relevant extracts from, the construction contract and such other documents as the referring party intends to rely upon.

9.31 The time for referral runs from the date the notice of adjudication is sent and not the date of receipt by the responding party.42 A referral notice received by fax after 4.00 pm is received that day and will not be deemed to have been received on the following day, as the Civil Procedure Rules do not apply to adjudications.43

9.32 In Hart Investments Ltd v Fidler and anor (2006) (Key Case),44 after considering the then conflicting authorities in relation to late decisions (discussed in at 9.37–9.44), the court found that the requirement for service within seven days in the Scheme is strict and cannot be extended; and if the referral notice is served outside that time then it is not a valid referral notice. The effect is that the dispute has never been referred, with the result that the adjudicator has no jurisdiction to decide that dispute. Shortly after this decision, the same principles were held to apply to the adjudication provisions of the JCT 1998 Standard Form (clause 41A.4.1) in Cubitt Building & Interiors Ltd v Fleetglade Ltd (2006).45 However, in that case, while the time limits were found to be mandatory, the service of the referral notice on the eighth day was permitted as being in accordance with a common sense interpretation of clause 41A.4.1.

9.33 In Lanes Group Plc v Galliford Try Infrastructure Ltd (2011)46 the court considered the question of whether a failure to refer in time affects the referring party’s right to start again with another notice, appointment, and referral. An earlier application for an injunction to restrain the referring party from making a further referral of a particular dispute was unsuccessful,47 although it was specifically only argued on the basis of repudiatory breach of the agreement to adjudicate. When the question was reconsidered at the enforcement proceedings it was held that there was no basis for implying an absolute or qualified bar to restarting an adjudication where there had been a previous failure to refer that same dispute in time and there was no prejudice arising from such conduct. This was upheld by the Court of Appeal.48 Akenhead J also said that failure to refer in time is, however, a breach (albeit non-repudiatory) of the implied adjudication agreement between the parties, which may sound in damages and could potentially lead to the court awarding injunctive relief.49

9.34 An element of flexibility has, however, been allowed in relation to paragraph 7(2) of the Scheme where there has been late service of documents supporting the referral notice, although it will always be a question of fact and degree whether the late documents make the referral so deficient that it affects the validity of service of the referral altogether.50