Judicial Architecture and Rituals

, Clément Camion2, Karine Bates3, Siena Anstis4, Catherine Piché5, Mariko Khan6 and Emily Grant7

(1)

Faculty of Law, McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada

(2)

Montréal, Québec, Canada

(3)

Département d’anthropologie, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada

(4)

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

(5)

Faculté de droit, Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, Canada

(6)

Sheahan and Partners, Westmount, Québec, Canada

(7)

Montréal, Québec, Canada

Efficiency lies at the heart of judicial reform in a time when public institutions face a situation of shrinking resources and when “managerial thinking” about justice is prioritized.1 The public is told that judicial systems need to undergo structural reforms in order to make dispute resolution more efficient. From this perspective, a concern for judicial rituals may appear anachronistic. A decision to adopt more efficient judicial structures would necessarily require a reduction in the use of judicial rituals, which can be time-consuming and expensive. But, before making the decision to discard judicial rituals in favour of efficiency, we need to ask two important questions. First, can disputes be resolved without judicial ritual? Second, would a de-ritualized dispute resolution process result in a loss of legitimacy for the entire judicial system?

In this chapter, we discuss the symbolic function of ritual in civil disputes and the necessity of such ritual in the judicial process. While retaining an anthropological and historical point of view, we review literature dealing with judicial ritual and judicial architecture, and address current issues in civil justice reform, including the fairly recent development of managerial requirements regarding justice. For the purposes of this study, we embrace a broad definition of judicial ritual . The term thus encompasses a number of practices used in dispute resolution, both past and present, such as ordeals, oracles, lottery-like games, courtroom customs, clothing, language, the rules of evidence and procedure, architecture, and other forms of nonverbal discourse. We generally see in judicial rituals an attempt to formalize the process of resolving a dispute.

Are rituals anachronistic? Do participants perceive them as useless? Is it possible to explain a ritual’s relevance without undermining its performative effect and, by way of consequence, the legitimacy of the judicial process? At the outset, it should be said that there is a tension between the concept of ritual and that of party autonomy. On the one hand, judicial rituals are imposed on users of a justice system in order to inspire authority and respect for dispute resolution. Procedural rules, on the other hand, can serve to establish party autonomy as fundamental to justice, especially, but not only, in the common law tradition. Indeed, procedural autonomy is so deeply engrained in our sense of justice that it is almost taboo to question it. Yet, judicial rituals interfere with this fundamental principle by limiting autonomy, defining and constraining how parties can act. Overall, we argue that, while the imposition of judicial rituals may run against a party’s interest in the short term, such rituals respond to the on-going need for broad social legitimacy that characterizes the institution of civil justice.

Judicial Architecture

Judicial Architecture as a Discourse

Is it possible to think about a justice system without material or physical representation? Is justice solely embodied in process and practice, or does judicial architecture—the place in which justice is rendered—have a purpose in the process of delivering justice? Academics trained in both civil and common law jurisdictions have noted the communicative importance of the physical manifestations of justice. In other words, where justice is delivered communicates, in and of itself, certain messages to its audience. These messages are carefully and consciously selected.

Scholars recognize that judicial architecture plays a key role within legal systems, expressing norms contained in law through visual representations. For this reason, “judicial architecture must be construed as an integral part of legal discourse.”2 Judicial architecture serves to communicate symbols that may otherwise be beyond the grasp of the layman and thus fosters access to justice by materializing notions that are abstract by definition.3

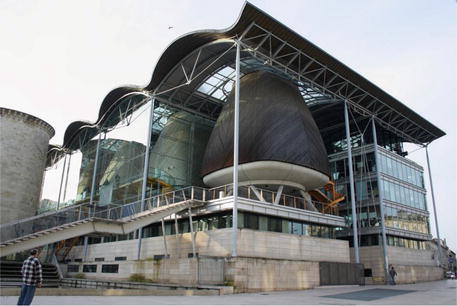

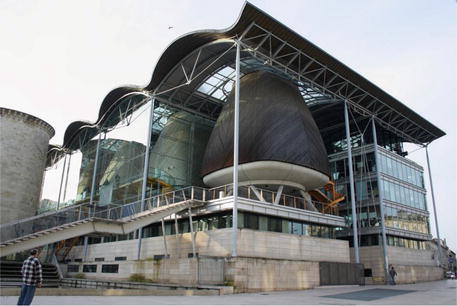

In France, for instance, Arnaud Sompairac has underlined the importance of judicial architecture through his contributions to general guidelines that form part of the programme architects must follow when designing new courts. He proposes three guiding principles. First, monumentality has to be expressed through a specific architectural vocabulary using, for example, columns, pediments, staircases, statuaries, etc. Second, transparency has to be used to create an open space for thought. Third, courthouses have to fulfill certain theatrical and pedagogical functions by staging judicial temporality through their designs.4 Figures 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3 present the exteriors of a selection of newly designed French courthouses, informed by these architectural principles.

Fig. 1.1

Extension of the Bordeaux courthouse (architect: Richard Rogers, 1997). “Bordeaux Palais de Justice” by GFreihalter (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 1.2

The Nantes courthouse (architect: Jean Nouvel, 2000). “Palais de justice @ Nantes” by Guilhem Vellut (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)], via Flickr

Fig. 1.3

The Pontoise courthouse (architect: Henri Ciriani, 2004–2005). “2005 PONTOISE” by ArchiModerne (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

In the same vein, David Marrani explicitly links judicial ritual and architecture with the development of a complex system of values. For this reason, rituals should be taken into account prior to designing a courthouse:

In the case of judicial architecture, what is interesting is the presence of a specific judicial ritual that mixes with architecture. There is a complex system of values that becomes connected to the “speaking architecture” where the building, which imposes the solemnity of the state, illuminates in turn its authority.5

This concern for judicial architecture is not particularly civilian; it is a concern shared by Anglo-Saxon, common law sensibilities. For UK law professor Piyel Haldar , the “aesthetic dimensions of the court-house, far from being a-political and incidental actually ensure the strength and force of an institutional order.”6 Linda Mulcahy shares the same opinion in noting that the building reveals much about prevailing notions of the relationship between the State, law, lawyers, and legal subjects through the medium of architecture.7 Australian law and humanities scholar Desmond Manderson also states that “how and what law means is influenced by where” this meaning is conveyed.8 David Tait highlights that Australian courts, as well as other public buildings, express the values of authority and sovereignty.9 Despite its strong ties to the civilian tradition, Québec is architecturally Anglo-Saxon, and Josiane Boulad-Ayoub posits that Québec courts, as a cultural and ideological institution, canvass cultural and political frameworks in the public sphere.10

Historical Perspectives on Judicial Architecture

From the Tree of Life to the Secular Cathedral

The history of judicial architecture has followed a broad movement toward rationalization and secularization. At the same time, there has been a shift from hearings held outdoors to hearings held indoors. The iconic outdoor setting is the tree of life. French historian Robert Jacob identifies the “tree of justice” and its branched enclosure as the most ancient and resilient symbol in judicial architecture. The tree of justice was originally a symbol borrowed from pagan mythology, standing for the universal support, stability, and regenerating function of justice. A circular enclosure made of branches delineated a space of symbolic fertility and of judicial peace where violence was prohibited. This wooden enclosure is still present in modern courthouses as what we commonly refer to as the “bar” (Fig. 1.4).

11

Fig. 1.4

Miniature of an outdoor session of the court of Mulhouse from the Diebold Schilling Chronicle, 1513, folio 70 v, courtesy of Korporationsgemeinde Luzern. Reproduced from Robert Jacob. (1994). Images de la justice. Paris: Le leopard d’or

The tree trunk, by which judges sat and from which they derived their authority, structured the judicial stage in important ways. It was both a symbolic axis discriminating between good and evil, and a symmetrical axis along which the parties were placed. This axis remains today, but it is now representative of a balancing of inequalities. The figure of God, in particular a Christ of Apocalypse symbolizing the Last Judgment, by which the judge would himself be held accountable, was also gradually affixed onto the tree and eventually replaced it. This figure remained in Germany at least until the Reformation, while a crucifix replaced it in France and remained until the lay laws of 1905 that consecrated the separation of Church and State.12

With secularization, Mulcahy notes a movement from the “primitive purity of trials in which God or Gods were deemed to have determined the outcome to the instability of a trial based on precedents and evidence.” She continues:

The purpose of trial by battle or ordeal was to reveal God’s will and . . . may well have reinforced the insignificance of humankind in the cosmos. Similarly, the early system of oaths in which supporters would assert the truth of a litigant’s case was founded on the notion that it was only the foolish that lie about such matters before God.13

The continuing influence of religion on judicial architecture should not, however, be underestimated. Mulcahy speaks of ongoing “subliminal religious symbolism” in courthouses. She mentions that courthouses may be construed as secular cathedrals, with all the sacral aspects of contemporary courts: an altar-like bench, a choir-like jury box, a lectern-like witness stand, and a rood screen separating the inner and outer segments of the room.14

From Outdoors to Indoors: A Short History of the Courthouse

Judicial spaces evolved over a long period of time.15 They began as outdoor spaces under a tree and transitioned to indoor spaces shared with other spheres of public life. Eventually, judicial spaces came to occupy houses dedicated specifically to justice. Finally, this evolution crystallized in the monumental ideal of a “temple of justice”.16

From the twelfth century onward, justice made its way indoors , with the administration of disputes at first occurring in numerous buildings dedicated to other public-life activities, such as in church entrances, above city gates, on the second floor of covered markets, and in castle rooms . In the vicinity of cathedrals, some ecclesiastical justice buildings appeared in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, while small seigneurial jurisdictions established hearing courts in small houses, constituting the first pieces of architecture dedicated entirely to administering justice. Such houses usually displayed a darker, carceral ground floor, sometimes shared by small shops, while the majestic, illuminated upper floor was reserved for adjudication. For Jacob , the symbolism is remiscent of hell and heaven, both floors being linked in a symbolic column representing the unity between earthly and celestial justice (Fig. 1.5).17

Fig. 1.5

A French justice-halle (built 1535, La Ferté-Bernard), including a covered market on the ground floor. “La Ferté-Bernard (72) Halles” by GO69 (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

The courthouse model in Europe gradually transitioned from a simple house to a temple or palace . A certain distancing between justice and its subjects took place between the Middle Ages and the classical period.18 By the sixteenth century, this process had reached its peak. Courthouses tended to have a square and symmetrical design. The building was not part of the surrounding environment; it was dominating, cut off from commercial activities, and closed to the outside world. Entering the courthouse had ceased to be a common act. It had become an exceptional circumstance, highlighted by an imposing structure. As described by Jacob, “Justice distances and elevates itself, surrounded by multiple symbolic defences.”19

These transformations were never gratuitous or the result of chance. Jacob finds evidence that magistrates had progressively theorized the ideal of a temple of justice and imposed it on architects, inspired by the return to classicism characteristic of the Renaissance.20 Yet, this architectural programme had only limited success. Multiple courthouses were built based on this ideal during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but probably as many traditional courthouses appeared during the same period.

From the French Revolution onward, however, the neoclassical style was omnipresent. At that time, penitentiary and judicial architecture became separate. More than half of all courthouses in the nineteenth century were built according to the temple ideal, materializing the theories of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century magistrates.21 In the twentieth century, no significant changes in courthouse architectural style appeared before the 1960s, and in examining developments since then, Jacob finds it difficult to identify any clear architectural trend.22

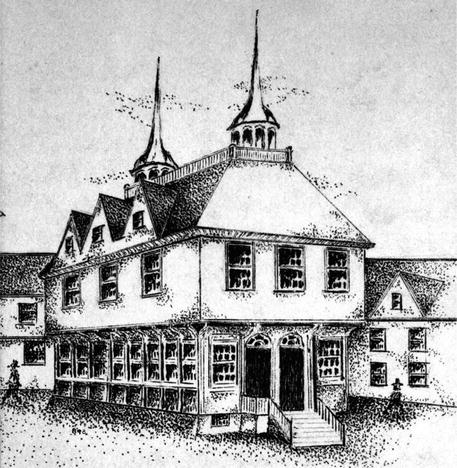

Although Jacob focuses mainly on the French history of judicial architecture, the broad trends he identifies are strikingly similar to those of British history. Mulcahy notes that justice was first administered without walls in ancient Greece, as well as in Teutonic and Celtic cultures, and gradually transitioned over the centuries to more contained, segmented, and segregated spaces. First, the administration of justice moved to shared public spaces (Fig. 1.6)—“soft” spaces capable of absorbing some of the legitimacy of the place to which they were adjoined—and then eventually to dedicated spaces. As an incidental effect of this transition, the role of the public was marginalized and reduced from that of active participants to docile bodies, with media and new technologies being confined overall to this segmenting function.23 Interestingly, Mulcahy traces the move indoors back to the association of procedure with written texts:

For some writers the enclosure of courts within buildings reflects broader shifts in attitudes towards adjudication and the nature of the authority on which adjudicators sought to draw. Graham (2004) has argued that the trend towards holding courts indoors . . . reflected the increasing association of legal procedure with the written word. . . .

. . . Douzinas and Warrington (1991) draw attention to the move from speech to writing in the English trial prompted by the slow transfer of religion from the public to the private sphere and the growth of literacy. Such transformations were by no means rapid but the growth of a “legal science” with its emphasis on the legal text rather than divine revelation has been traced back to the twelfth century when the first law schools were established specifically for the purposes of studying ancient manuscripts. From a position in which it was expected that the will of God would reveal itself, through for instance an ordeal by fire, Goodrich (1987) argues that in time it was the text which revealed the wisdom of the deity or their disciples and was treated as a sacred source. It can be surmised that once it was the text which was seen to contain a complete and integrated body of doctrine from which all deductions could be made . . . natural elements became less important in the process of adjudication and a new type of priest emerged in the form of the lawyer.24

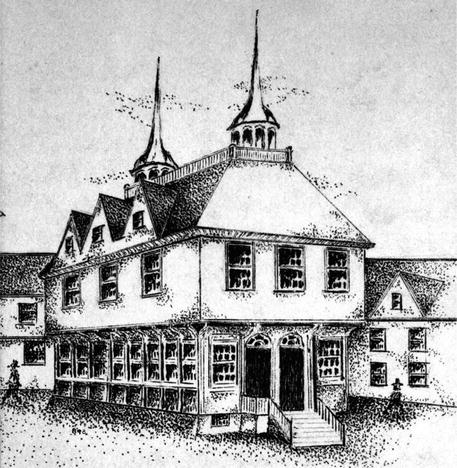

Fig. 1.6

Conjectural drawing (c. 1898) of Boston’s First Town-House (1658–1711), a shared judicial space modelled on Medieval British town halls. The town-house included an open-walled market on the first floor and upper rooms used for judicial hearings. “First Town House 1” by BPL [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Mulcahy argues that, despite reliance on designated spaces of justice in the present day, “the notion of courthouses and courtrooms having fixed spatial identities continues to be contested.”25 The dominant practice of using architecture to create distinct judicial spaces may obscure, at least in part, a role for ritual in defining activities as judicial even in the absence of a designated courthouse- or courtroom-like space. Indeed, some policy-makers still turn to the idea of multifunctional spaces that could house judicial proceedings alongside other kinds of activities.26

The Power of Symbols in Judicial Architecture

A study of judicial architecture must also consider the role of judicial symbols. What is the normative scope of these symbols? Are they descriptive of justice as it is, or prescriptive of justice as it ought to be? How does the public interpret these symbols? Are such symbols misleading insofar as they aim to create an impression about justice that is inaccurate?

Concerning the potential for symbols to mislead, glass may, for instance, be used in courthouse design to emphasize the transparency of a justice system, though the system may not live up to this characterization in reality.27 Thus, while symbols are meant to enhance the legitimacy and strength of justice systems, they may fail to do so if there is a contradiction between the message sent by such symbols and the actual workings of justice.

Another example of symbolic contradiction concerns the depiction of courts’ relationship to other branches of government. Resnik , Curtis, and Tait argue that monumentality in courthouse architecture narrates the prestige accorded to “the independence of the judge” but should also serve as a reminder of the “dependence of the judicial apparatus on the state for its financial wherewithal and materialization.” In this light, further regard may be required concerning “democratic courts’ commitments to their citizens,” particularly the right to public hearings, in a time of increased privatization of dispute resolution.28

Judicial Architecture as Reflecting a Justice Closer to Its Subjects

Reforms aimed at addressing the need, discussed above, for a democratization of justice have given rise to judicial architecture that emphasizes accessibility, mirroring procedural practices that have embraced private justice as a means of access to justice. Philosophy professor Josiane Boulad-Ayoub argues that Montréal’s Palais de Justice, a modern tower built in 1971 that resembles downtown office buildings, symbolizes the democratization of justice and the closing of the distance that long existed between justice and its subjects.29 For her, analysis of the numerous symbols encrypted in previous neoclassical courthouses only depicts what an educated bourgeoisie may have been capable of seeing in such buildings. The laymen most probably perceived all these symbols as an impressive “thing”, effectively inspiring respect without necessarily promoting education, understanding, or admiration. Today, the 1971 courthouse design is closer to people’s everyday life, although its dark minerals and glass, wide spaces, and 17 floors still project an aura of solemnity. David Tait argues likewise about Australia’s renewal of judicial spaces, with recent designs moving justice closer to the will of the sovereign people (Fig. 1.7).30

Fig. 1.7

The Montréal court house (architects: Pierre Boulva and Jacques David, 1971). “Palais de Justice de Montreal 05” by Jean Gagnon (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

This recent democratization of courthouse design must be understood in light of judicial architecture’s history of responding to society’s changing attitudes and expectations regarding justice , which is linked in turn to the history of procedural practices.31 In the Middle Ages, pleadings of justice—royal, seigneurial, or ecclesiastical—were heard before thousands of people. The duty to render justice was mostly that of the prince toward his subjects. Along with theories of sovereignty, rendering justice played a key role in legitimating the nascent political structure of the modern State; subjects’ need for dispute resolution was used as an opportunity to impose norms upon them and demonstrate the State’s power and legitimacy. Then, by the seventeenth century, a certain stigma was attached to litigation. Politics became the subject of interest and admiration, taking the place of the fluid and abundant justice of previous centuries. By the nineteenth century, the long process of rationalizing and concentrating legal norms and political legitimacy culminated in the French Revolution and Napoleonic laws.32

Today, there appears to have been a shift. Our era is characterized by the promotion of a minimal State33 and of alternative dispute resolution (ADR)—that is, private justice, sometimes court-annexed. It is also characterized by the recognition of legal pluralism and global inter-normative influences. Multiple public or self-regulated private juristic orders combine with increasingly predominant recourse to private justice, both domestically and internationally. In the meantime, there is a constant aspiration to reconnect justice with its subjects, to make it more local and accessible, but also more responsive to the needs of globalization. While these trends may be reminiscent of the multiple decentralized and more or less private juristic orders of the Middle Ages, we have also reached a different stage in judicial government. Antoine Garapon argues that after the ritual and disciplinary ages of justice, we now live in the age of managerial justice.34

Judicial Rituals

Theoretical Accounts of Judicial Rituals

In this part, we examine the concept of judicial ritual, in particular through its relationship to party participation in judicial proceedings and its consequences for the autonomy and dignity of individual parties.

For the purposes of this study, we define ritual as a pattern of repeated formal conduct that has acquired normative effect. This definition is rooted in the work of scholars who have emphasized that rituals are essentially social constructs, and thus produce certain effects by shaping people’s behaviour in public. In this respect, Erving Goffman has shown that a fundamental need to appear coherent and thus to save face in social interactions is fulfilled when abiding by rituals, that is, the implicit code of conduct of a given community and the common expectation that such code will be upheld by participants.35 Goffman further shows that rituals can be used to “frame” a particular situation in order to organize people’s experiences and manage their impressions.36 Judicial rituals play that role of staging authority and power.

Our proposed definition thus ascribes to judicial rituals a dimension of form and a dimension of effect, which are considered to be interdependent to some degree. The effect of ritual, that is, its normativity as an implicit code of conduct, is at least in part a function of a repeated formal process, or pattern of conduct, generating the expectation that the code will be upheld. At the same time, as Goffman highlights, the normative dimension of ritual can also be deployed to manage or organize behaviour and therefore has the potential to shape parts of the pattern of conduct that constitutes a ritual’s form.

It must also be noted that critical accounts of judicial rituals warn against sacralizing judicial rituals that have fallen out of favour or whose relevance has only been perfunctory. In particular, there is a risk that such practices may come to be viewed as fundamental rules that cannot or should not be changed by judicial reform. As Pierre Noreau notes, judicial rules mirror society itself in the sense that they do not evolve in a linear fashion, but rather are the result of complex social processes.37

Under this definition, judicial rituals include rules of evidence and procedure. Procedure, although not necessarily impressive in and of itself, is an effective tool for inspiring respect for the law, including among members of the legal profession.38 As Mariana Valverde writes:

[T]he effectivity of law is also accomplished through a number of quite humdrum techniques and procedures that bear little trace of the sovereign’s majesty. Perhaps precisely because of their lowly status as mere technicalities and unspoken rules, these procedures work quite effectively to create loyalty to law’s power not only among the accused or among the populace that observes the legal rituals but even among those who appear in the role of co-sovereigns.39

Further:

Law’s sovereignty is organized and maintained not only by majestic spectacles but also by the quiet operation of the technical but never trivial details of something as non-majestic as the rules of evidence or the unwritten rules governing dress and speech. My own experience of law shows that at least in some instances law acts not as a sovereign but rather as a seducer whose ability to generate willing, loyal and even loving subjects lies precisely in “formalities”, in technical rules and in unspoken agreements to preserve law’s illusion of autonomy simply through acceptance of rules not only of procedure but also of decorum. The formal and informal procedures, those created by judges and – perhaps most importantly – those not made by anyone in particular but introjected by participants and spectators alike are precisely what bind the expert loyally to law, all the while detaching her or him from the social movements from whence she came.40

Valverde’s perspective conflicts with the finding by social psychologist Tom Tyler that satisfaction of the parties about the judicial process is better achieved when they are drawn to participate actively in the process.41 In Valverde’s view, passive participation is suggested as being sufficient. The parties are involved without necessarily understanding the ins and outs of the judicial ritual. This suggests a potentially salutary form of paternalism.42 But it also raises the question of the correct balance between judicial ritual and the parties’ autonomy and dignity,43 the latter of which is, at least in principle, better promoted through active participation in the choice of the procedure to which the parties will subject the resolution of their conflict, as is the case, for instance, in arbitration and, to varying degrees, in mediation. Depending on the value placed on respect for the parties’ autonomy, a civil justice system may decide to promote party “empowerment” instead of imposing judicial rituals; yet another could require that parties themselves create the rituals to which they will be submitted.

A consequence of courts’ tendency to confine their activities to court procedures, as opposed to other forms of dispute resolution, is that citizens only experience judicial rituals in which they feel like, and are expected to act as, objects rather than agents , a phenomenon that Noreau refers to as “institutional distancing”.44 Architecture and the use of space can have a similarly debilitating effect. Mulcahy underlines the difficulty for witnesses of “appearing confident while describing intimate experiences to others across a large intimidating courtroom”: “[A]rchitecture can be used to inhibit understanding and discourage participation, while also engendering fear and respect. In short, the exploitation of courtroom space can have a paralysing effect on those who are not regular users of the court system and can serve to contribute to a ritualised stripping of dignity.”45

Judicial Rituals Within the Legal Culture

Judicial rituals should be analyzed as part of the broader context in which they exist. They belong to a larger ensemble of “legal culture”. Legal culture is made up of rites and usages, and contributes to producing and reproducing legal institutions, hierarchies, and sets of rules. Clothing, attitudes, and even presence at certain meetings of the legal community are indicators of a willingness to constitute the legal profession as a coherent body and thus as comprising its own culture. For example, lawyers’ distinctive gowns are an attribute geared toward guaranteeing the dignity and prestige of the profession.46 For some, procedural formalism constitutes the core ritual of any given legal culture. Western legal culture is more often than not made up of procedures, practical knowledge, and know-how learned on the job, with formulas tirelessly repeated to build up learned arguments and deliver them at trial.47 The French expression effet de toge, literally “gown effect”, describes the very peculiar eloquence sometimes displayed by lawyers, a combination of ample gesture and vigorous speech that is both admired by the public as impressive and mostly disregarded by judges as ineffectual.

Following law professor Daniel Jutras , one can distinguish between the political, the professional, and the normative aspects of legal cultures. In Québec, for example, the liberal, North American political culture of litigation incorporates marginalization, desacralization, market-oriented thinking, and the possible politicization of civil justice. The professional, common law culture is individualistic, liberal, adversarial, and to a large extent oral. Finally, the normative culture is rather civilian in nature, integrating procedural and substantive law.48 These are among the multilayered influences we should bear in mind when thinking about what shapes judicial rituals, how they are perceived, and the value they should be ascribed.

From a normative standpoint, legal culture may be a factor of resistance to change in the law .49 For example, Noreau identifies legal culture as a major impediment to civil justice reforms proposed by Bill 28, An Act to Establish the New Code of Civil Procedure in Québec.50 At the same time, however, anthropologists note that the repetitive character of rituals does not imply that they are unalterable or timeless. Throughout time, societies have invented and reinvented social practices, including rituals based on the understanding that the power of rituals derives from the State, society, ancestors, God, or other external sources. For example, it is the authority of the State and the constitution that makes people rise as the judge enters the courtroom. People do so not because they feel like it or because they particularly respect one individual judge, but rather because they recognize the authority bestowed on the figure of the judge. Judicial rituals may thus be subject to change because their normative force is viewed as a function of external, cultural considerations, rather than based on factors internal to or inherent in the form of a particular ritual itself.

On the Rationality of Judicial Rituals

Law as Magic

An analysis of judicial proceedings reveals a role for judicial rituals in legitimizing decisions, which stands in contrast to dismissals of rituals as irrational and which efficiency-seeking civil justice reforms must take into account. For early-twentieth-century American realists, rituals obstructed empirical, rational legal demonstrations. Rituals such as the stare decisis doctrine, doctrinal formulas, and rules of procedure were considered to be nothing but “magic solving words”, “word ritual”, or “legal myth” concealing the influence of personal preferences and ideology on decision-making.51 Challenging this belief, Jessie Allen argues that irrational features of judicial rituals may, on the contrary, support enforcement of adjudication in society while ascribing meaning to judicial decisions. In making this argument, Allen relies on the works of modern anthropologists such as Bronislaw Malinowski, Stanley Tambiah, Edward Evans-Pritchard, Victor Turner, and Mary Douglas to argue that magic and rituals are not necessarily irrational and that they may serve to support both the legitimacy and efficiency of law.52

For instance, in the sub-Saharan dispute resolution ritual palabre , although the lengthy, open-ended discussion that defines the ritual may lead to gathering information and passing on knowledge, the main goal is not to determine who is right or wrong. The goal is rather to re-establish social bonds and to maintain group cohesion . The process must benefit every party and the decision or outcome must be somewhat satisfactory to everyone involved in order to make sure that even the losing party is reintegrated into the community.53 In this respect, community cohesion is paramount; decisions affecting the community must thus be made by and for the community. There is no omnipotent, external, or everlasting notion of justice. Law is local, internal, and tailored to each group. This is not to say that there is no endeavour to clarify the facts of a case. The parties are asked to present their version of the facts. Questions are asked, especially during stages preliminary to the grande palabre, usually through the parties’ representatives.54 During the grande palabre, however, it is mostly the party representatives who intervene. The palabre consists in staging and formalizing the parties’ roles through symbolic mediations, such as oaths and ordeals, as well as real mediations, with each palabre being preceded by mini palabres.55

It is thus very important to compile the facts and obtain accurate information in order to avoid arbitrary decisions capable of undermining social bonds. With this logic in mind, calling upon an invisible realm, for instance through oracles, for the purposes of validating a certain version of the facts of a case or confirming that one party is guilty, is not necessarily irrational . Social organization takes into account both the visible and the invisible because spiritual forces have an impact on both. As an African proverb goes: “The defunct is never dead so long as someone thinks of him.” Norbert Rouland thus writes that the dead do not leave for a far and unreachable destination. They are present beside the living and attack or protect them as much as they depend on them. There must therefore be some sort of unity between the visible and the invisible.56

Dispute resolution mechanisms cannot always be framed according to Western law. Judicial processes are behavioural codes determined by the values prioritized by a community and the results it wants to achieve . For example, consider the palabre again. The nature of a dispute has no influence over where the palabre takes place. Thus, all disputes are treated the same. Moreover, oral proceedings are flexible enough to give way to negotiated dispute resolution. As Rouland remarks, these rituals show that conciliation has priority over pre-established, rule-based decision-making. Unanimous decision-making on important issues is preferable and should not result in the victory of a majority over a minority that would ultimately be perceived as a social divide. Palabres, which can last several days, thus play the important role of progressively reducing diverging opinions among the participants (Figs. 1.8 and 1.9).57

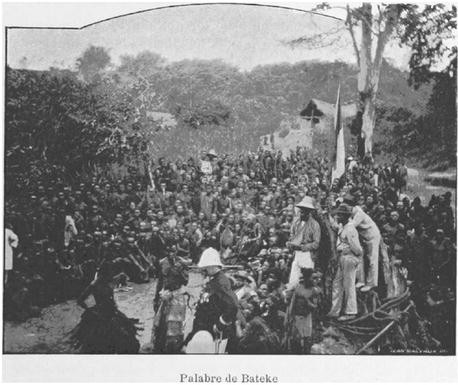

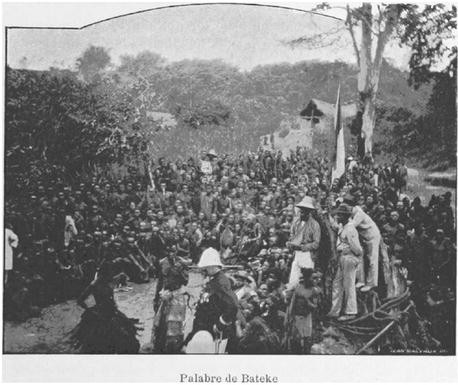

Fig. 1.8

A historical photograph of a palabre held by the Central African Teke people. Note the presence of a colonial official in the foreground. From Vandrunen, J. (1899). Heures africaines: L’Atlantique-Le Congo. Bruxelles: Ch. Bulens. p. 177

Fig. 1.9

A modern palabre space in the village of Endé in Mali, consisting of a low, open-walled building. In other traditions, palabre are held outdoors, usually under a tree. “Togunat 01” by Taguelmoust (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Although palabre does not follow the same rules as Western trials, arbitrations, or mediations, it is not an improvised, rule-free process. It has its own internal logic and is designed to achieve specific goals. This is not an isolated phenomenon . For example, Evans-Pritchard has demonstrated that the system of Azande beliefs and practices concerning oracles, witchcraft, and magic is rational if one assumes that invisible forces co-exist in the visible world and that nothing happens to people by accident.58

Allen’s view, discussed above, is similar to that of Thurman Arnold , which Allen refers to as “magic realism”. Magic legal realism posits that symbolic aspects of judicial practices are useful and have practical relevance59; the character of judicial systems would thus be profoundly altered if we were to do without this folklore and spiritualism .60 Allen theorizes judicial rituals as “a ritual-magic mode of adjudication that is not necessarily contrary to legal reason.”61 The primary function of adjudication is not to explain the decision but to transform the social fabric:

[L]aw constitutes and transforms social meaning by helping to create and recreate the social situations at issue in adjudication. Ritual magic is a long-recognized mechanism of such transformations.

In law, as in ritual magic, transforming the meaning of a set of social circumstances can happen through common formal and performative techniques that may look like mere distractions or ways to disguise what is really going on. In fact, some functions of law in our society may depend on these techniques, not because they confer logical-rational correctness or predictability, but because they may contribute to judicial impartiality and because they may provide a mechanism through which official legal decisions take on some of the affective power of lived experience and so generate the personal and collective commitment that leads to social transformation.62

One consequence of acknowledging the practical functions of a judicial proceeding’s symbolic aspects is the need to accept that judicial proceedings seek more than just the efficient resolution of disputes, as is evidenced by the immense importance of the trial as a public theatre. For Thurman Arnold, a trial (and particularly a criminal trial), “represents the dignity of the state as the enforcer of law and at the same time the dignity of the individual even though he be an avowed opponent of the state.”63 While a trial often fuels contentious public discussion, it also acts as a stabilizing agent. As he underlines, “So important is the public trial to the whole ideological structure of any government that the adoption of more efficient and speedy ways of punishing individuals is a sure sign of instability and insecurity.”64

Despite the need to appear logical and coherent, the foundational principles of a judicial institution must also be flexible enough to allow for the staging of mutually exclusive ideals. The main challenge for lobbyists and supporters of judicial reform is that of accounting for the role of symbolism in society : “A people will never accept an institution which does not symbolize for them the simultaneously inconsistent notions to which they are at various times emotionally responsive.”65 Trials can support a number of principles and ideals that have no particular importance to the case at hand, but that are of the utmost importance as a symbol of justice in its abstract form.66 Law can be seen as a large pool of social symbols capable of provoking emotional responses67:

It is child’s play for the realist to show that law is not what it pretends to be and that its theories are sonorous, rather than sound; that its definitions run in circles; that applied by skillful attorneys in the forum of the courts it can only be an argumentative technique; that it constantly seeks escape from reality through alternate reliance on ceremony and verbal confusion. Yet the realist falls in grave error when he believes this to be a defect of the law. From any objective point of view the escape of the law from reality constitutes not its weakness but its greatest strength. Legal institutions must constantly reconcile ideological conflicts, just as individuals reconcile them by shoving inconsistencies back into a sort of institutional subconscious mind. If judicial institutions become too “sincere,” too self-analytical, they suffer the fate of ineffectiveness which is the lot of all self-analytical people. They lose themselves in words, and fail in action. They lack that sincere fanaticism out of which great governmental forces are welded.68

Arnold draws attention to a particularly sensitive aspect of judicial rituals in the civil justice reform movement. He believes that, even though efficiency is necessary in bringing about legitimate justice, there is a point beyond which efficiency, by desacralizing judicial rituals to the extreme, undermines the legitimacy of judicial decisions :

The ceremonial trial never is, or can be, an efficient method of settling disputes. Of course efficiency is one of its ideals, but there are others equally important which must also be dramatized. Therefore, if we want real speed, or efficiency—in other words, if results are more important than the moral lessons which are to be taught by the process—we move the settlement of the dispute into a less symbolic atmosphere. We find this atmosphere in what we call administrative tribunals. Yet in a climate of opinion which demands the comforting belief that there is a “rule of law,” the administrative tribunals never quite satisfy us, and the ceremonial trial continues as a method of resolving all disputes concerning which philosophical argument is possible.69