Japan

JPY (%)

Japan

2007

U.S.

2007

E.U.-27

2006

Germany

2006

France

2006

U.K.

2006

China

2006

Korea

2006

Total R&D

Expenditure

(in trillion JPY)

18.9

43.4

31.3

8.6

5.5

5.0

4.4

3.3

(% Public R&D)

(17.4)

(27.7)

(34.2)

(27.8)

(38.4)

(31.9)

(24.7)

(23.1)

(% Per GDP)

(3.67)

(2.68)

(1.84)

(2.54)

(2.10)

(1.78)

(1.42)

(3.23)

GDP

(in trillion JPY)

516

1,618

1,704

339

264

279

308

103

and their relation to the anti-monopoly act. The fifth section lists some important anti-monopoly cases related to intellectual property. The sixth section describes the recent amendments to the anti-monopoly act enacted in January 2010, and the final section concludes the chapter.

II. Overview of Japan’s Anti-Monopoly Act[1]

The Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade (Act No 54 of 14 April 1947; hereafter AMA) aims

to promote free and fair competition in markets, to stimulate the creative initiative of entrepreneurs, to encourage business activities, to heighten the level of employment and actual national income, and thereby to promote the democratic and wholesome development of the national economy as well as to assure the interests of general consumers. (Article 1.)[2]

Drafted under pressure from the occupation forces, many provisions of the AMA resemble the US federal antitrust laws, namely, the Sherman Act,[3] the Clayton Act,[4] and the Federal Trade Commission Act.[5] The AMA comprises four major categories of regulations:

1. Prohibition of unreasonable restraint of trade (latter clause of article 3).

2. Prohibition of private monopolisation (former clause of article 3).

3. Prohibition of unfair trade practices (article 19).

4. Regulations on mergers and acquisitions (chapter 4).

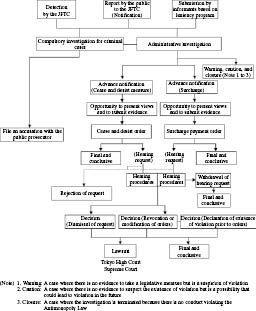

The regulations on the unreasonable restraint of trade control horizontal anti-competitive activities, including cartels and bid-rigging. The regulations on private monopolisation prohibit any exclusion or control of the business activities of other firms that leads to a substantial restraint of trade in a relevant market. Unfair trade practices refer to certain business activities defined in article 2.9 of the Act, and are designated by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (hereafter, JFTC), the primary regulator on the AMA. Conducts subject to the regulations of unfair trade practices include activities such as abuse of superior bargaining position, unjust low price sales, and refusals to sell. It has been widely believed that it is easier to establish a violation of unfair trade practices, which requires ‘a tendency to impede fair competition’ than to establish a violation of the provisions prohibiting unreasonable restraint of trade or private monopolisation, which requires ‘a substantial restraint of trade’. The JFTC also regulates business combinations, including mergers and acquisitions. It is interesting to note that the JFTC and courts have not made any formal decision on business combination cases since the year 1970, when Fuji and Yawata merged into Nippon Steel, then the second largest steelmaker in the world.[6] Instead, almost all business combination cases have been dealt with in informal consultations, which are not stipulated in the AMA, but strongly encouraged by the JFTC in practice.

III. Structure of Japanese Antitrust Enforcement

In the United States, the Government delegates antitrust enforcement to two agencies: the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (hereafter, DOJ), and the Federal Trade Commission (hereafter, US-FTC). While the AMA emulated the American antitrust laws, antitrust enforcement in Japan does not resemble the practices in the United States. Unlike the case of the United States, in Japan there is only one antitrust agency—the JFTC, which was established by the AMA (article 27). The JFTC was apparently modeled after the US-FTC: it is an independent agency under the Prime Minister’s Office. The JFTC has five commissioners, including one chairperson who is appointed by the Prime Minister with the consent of both House of the Diet (article 29). Each commissioner has a five-year term (article 30), and they are protected against pay cuts (article 36) or removals without cause or their consent (article 31). Decisions are made by a majority vote; however, minutes of meetings of the Commission have not been published.

Having only one antitrust agency responsible for enforcing the Act helps promote the development of a uniform national competition policy. Under the structure of the AMA, almost all basic antitrust violations are covered by the regulations on unreasonable restraint of trade, private monopolisation and mergers. It has long been argued that unfair trade practice regulations are not needed in Japan as the country has one regulatory agency, and these regulations were originally expected to serve merely a supplemental role in antitrust enforcement. Otherwise, the regulations on unfair trade practices would engender unnecessary confusion in the application and enforcement of the AMA, because violations covered by the regulations on private monopolisation are also covered by those on unfair trade practices. Furthermore, it has often been considered that the unfair trade practices category of regulations required a lower standard of anti-competitive effect than those required under the unreasonable restraint of trade and private monopolisation categories, as unfair trade practices in general did not require adverse effects on competition in the relevant market, whereas unreasonable restraint of trade and private monopolisation do require the adverse effects. As such, there were fewer sanctions concerning unfair trade practices than other regulations: while the JFTC can issue a cease-and-desist order on unfair trade practices, it is bound to order a surcharge payment if it found a violation of the provisions governing unreasonable restraint of trade and private monopolisation (but only when related to controlling business entities). The new amendments enacted in January 2010 have expanded the coverage of surcharges on unfair trade practices, as discussed in further detail later in the chapter.

IV. JFTC Procedures for Antitrust Cases

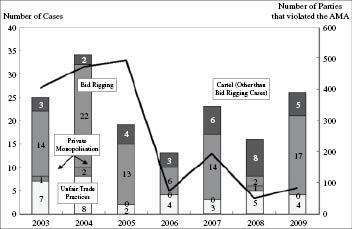

The JFTC’s current legal procedures for handling cases are shown in Figure 1. If a preliminary finding indicates that a violation exists, the JFTC initiates a formal investigation. The 2005 amendments have enabled the JFTC to exercise compulsory criminal investigations on cartel cases. After a formal investigation, if the JFTC finds a violation, it issues a formal order—a cease and desist order and/or a surcharge order—after having provided the respondent firm with an opportunity to present views and submit evidence. Subsequently, the JFTC initiates a formal Shinpan hearing upon the request of the respondent. The Shinpan hearing adopts the adversary system, in which independent referees, who are members of the JFTC staff, make a judgment. The structure of the Shinpan hearing has long been criticised as being rather inquisitorial, because within the JFTC staff, no clear firewall has been erected between Shinpan referees and Shinpan prosecutors.[7]

Figure 1: JFTC Procedures for Handling Illegal Cases Based on the Anti-Monopoly Act

During the formal hearing, the respondent firm may challenge the JFTC’s fact finding and application of the law, and make a remedial proposal. If the JFTC finds that the remedy proposed by the respondent is appropriate, the JFTC drops the case, and orders the firm to perform the remedy. If the JFTC finds that a violation exists, the JFTC issues a formal decision at the end of the Shinpan hearing procedure, ordering the firm to perform the remedy.

If the parties are dissatisfied with the decision delivered after the Shinpan hearing, they may enter into litigation at the Tokyo High Court, which has exclusive jurisdiction to revoke the JFTC judgment. Under the judicial review, the Court is bound by facts found in the JFTC’s decision if such facts are ‘supported by substantial evidence’ (article 80). If the courts find that a reasonable person would reach the same conclusion based on the same facts as the JFTC did, the courts should abide by the JFTC’s findings. Thus, under the judicial review, the plaintiff would argue that the facts on which the JFTC’s decision is made are not supported by substantial evidence. The plaintiff may also file an appeal against the judgment of the Tokyo High Court with the Supreme Court.

The Japanese Government has proposed significant changes to the procedures for challenging orders issued for antitrust violations by the JFTC. The Cabinet submitted a bill of amendments to the AMA to the House of Representatives (Shugiin) in March, 2010[8]. The bill provided for the abolition of the administrative hearings on alleged antitrust violations that currently are conducted by the JFTC, and will establish certain due process rights for parties being investigated prior to the issuance of a JFTC order.

In addition to abolishing JFTC hearings and revising the process for court review, the bill would provide certain due process protections for parties under investigation by the JFTC, including requiring that the JFTC:

— provide an explanation of the content of an anticipated order

— allow the parties informally to present arguments and evidence to the JFTC

— allow them to review evidence obtained by the JFTC from the party and its employees, absent legitimate reason for refusing access to those materials.

The ability to review such evidence is regarded as important for parties’ to prepare to challenge the order in the Tokyo District Court.

A. Sanctions

The AMA is normally enforced by the JFTC through administrative procedures, such as cease and desist orders and surcharge payment orders; however, criminal and civil procedures in court may also be instituted in court in some cases, as is briefly summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Sanctions under the Current AMA

Unreasonable restraint of trade | Private | Unfair trade practices | ||

Cease and desist order | Y | Y | Y | |

Surcharge | Y for price fixing cartel | Y | Y+ | |

Criminal Sanctions | Y | Y | N | |

Civil Procedure | Injunctive relief | N | N | Y |

No-fault | Y | Y | Y | |

Note: Y (or N) refers to the fact that a particular sanction is applicable (or not applicable) to certain anti-competitive behaviour.+: Surcharges applies to certain types of unfair trade practices, including concerted refusal to deal, discriminatory pricing, unjustly low price sales, and resale price maintenance.

The surcharge system was introduced in 1977. Surcharges are a rigid administrative fine. There are two aspects to the rigidity: first, the JFTC is obliged to issue a surcharge order if it is applicable, as listed in Table 2. Second, the amount of the surcharge is calculated according to a formula, namely, as a percentage (stipulated in the Act) of the profit received from the sales of products or services related to the anti-competitive activity involved.[9] The percentage of surcharge rate differs by the capital or total amount of contribution and lines of business, not by the severity of damages or the amount of excessive profit accrued by the alleged anti-competitive behaviour. Also note that in calculating the surcharges, the JFTC takes into account only domestic sales. Thus, it is currently impossible for the agency to collect fines from those foreign companies, for example, that participate in cartel activities by not selling to Japan. We believe that the current surcharge system is out of date in the era of a globalised economy where cross-border transactions are common. While it is often argued in Japan that a discretionary administrative fine is against transparency and predictability from the respondents’ point of view, we think it worthwhile to reconsider introducing a discretionary surcharge system. Such a system is more in line with the original purpose of the surcharge, in that it accounts for the difference in the amount of disgorged undue profit. Of course, calculating the appropriate amount of a discretionary surcharge requires the economics discipline.

B. Civil Procedure

The no-fault compensation suit is a private lawsuit specifically prescribed under article 25 of the AMA. The damage award is not trebled: instead, single damages are payable. A firm whose interest is seriously injured by unfair trade practices may seek injunctive relief from the court for suspension of such conduct (article 24 of the Act). Both of these private actions have not worked properly. It is presumably because plaintiffs, under the civil litigation procedures in Japan, do not have sufficient capacity to collect evidence to prove violations. As we will discuss below, these private actions can in principle be a complement to, rather than a substitute for, JFTC’s enforcement, and thus should be activated effectively.

V. Overview of Japan’s Intellectual Property Laws

Japan has enacted intellectual property statutes, including the Patent Act,[10] the Utility Model Act,[11] the Copyright Act,[12] the Trademark Act,[13] the Design Act,[14] and the Unfair Competition Act.[15] Japan has also entered into most of the important international conventions related to intellectual property rights (IPR).[16]

Textually, the IPR laws of Japan closely resemble those of other developed countries. The Patent Act, for example, provides for the patenting of inventions of products and processes, if the inventions satisfy the statutory requirements of novelty, utility and inventiveness.[17]

Like most such laws, with the notable exception of the US Patent Act,[18] the Patent Act gives priority to the first to file an invention, not the first to invent or use an invention, although an independent inventor who used the invention prior to the filing of the patent may continue to use the invention on a non-exclusive basis.[19] Until a decision rendered by the Japan Supreme Court in 1998, Japanese courts rarely applied the doctrine of equivalents, also engendering significant criticism. That may have changed with the Supreme Court’s 1998 decision in Tsubakimoto Seiko Co Ltd v THK K.K. Japan Supreme Court Case No 1994 (o) 1083, decided 24 February 1998.[20]

Some differences, however, stand out, including the lack of any requirement in the Japan law to disclose the best mode of practice of an invention, and apparently no Japanese court has ever invalidated a patent for a failure to disclose the best mode.[21]

The Japan Patent Office (JPO)[22] examines all applications and grants or denies patent applications. During the 1990s, various countries, principally the United States, alleged that the JPO showed favouritism towards Japanese patentees, those complaints have now waned and Japan’s patent issuance regime is now regarded as generally fair and effective. The court enforcement of patent rights were also broadly criticised as offering insufficient damages, and inefficient and costly procedural hurdles, including the length of litigation, high filing fees, limited discovery, and the absence of judicial authority to increase damages for willful infringement.[23]

Those concerns have been addressed substantially by two rounds of amendments to the Japan Code of Civil Procedure[24] in 1998,[25] 2004,[26] and 2006, as well as by 1999, 2007, and 2009 amendments to the Patent Act. The 1998 civil procedure reforms permitted plaintiffs to file intellectual property cases before the Tokyo or Osaka District Court, which each have a specialised intellectual property division and thus have more experience and expertise to handle intellectual property cases. They also sought to address concerns about the length of intellectual property litigation by concentrating formal hearings within shorter time periods and encouraging more expeditious handling of such cases, and by providing for meaningful preliminary hearings to focus the claims and defences and to permit the judges to meet with the parties, examine documentary evidence and discuss the issues on which the court should hear from witnesses. The 1998 amendments further empowered the courts to set specific time limits for submission of parties’ arguments and evidence, and the power to reject claims or defences not raised early in the case, and increased the obligation of parties to produce documents and the rights of the parties to seek information and documents, though the amendments, and courts interpreting the amendments, imposed a stringent level of specificity for such requests to be effective, which limited their effectiveness.

The 2004 amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure added procedures to further expedite cases, especially in complex litigation such as patent cases, urging disposition of cases within two years, and requiring courts and parties to seek to establish a schedule for all proceedings, with recommended deadlines.[27] The amendments also gave the Tokyo and Osaka District Courts exclusive jurisdiction over first-instance intellectual property cases and further expanded the rights of parties to seek information and documents from opponents. They also empowered the courts, in complex cases such as intellectual property litigation, to appoint ‘expert commissioners’ to provide their views in writing or orally, and even to participate in settlement conferences.[28]

Of the numerous rounds of recent amendments to the Patent Act, those that became effective in 1999 were the most relevant to the handling of intellectual property litigation and other issues that may bear on the intersection between antitrust and intellectual property law. Specifically, those amendments augmented the courts’ power, under the amended Code of Civil Procedure, to order a party to produce documents needed to prove infringement, and incorporated into the patent law the in camera procedure found in the 1998 amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure.[29] The Patent Act amendments also require a defendant to explain its acts that purportedly rebut an allegation of infringement, absent a proper reason for refusing to do so, providing plaintiffs with a more detailed understanding of the defendants’ theory of the case at an early stage in the litigation.[30]

According to various sources, these reforms appear to have reduced the duration of district court intellectual property litigation and increased damages awards during recent years. From 1999 to 2005, the average deliberation period of resolved intellectual property suits in Japan decreased from an average of 23.1 months to 13.5 months.[31] The average amount of damages awarded in ‘major lawsuits’ regarding infringement of patents and utility models also increased from an average of JPY 14.81 million (approximately US$145,000) in the 1975–79 period, to an average of JPY 111.36 million (approximately US$1,100,000) during the 1998–2000 period.[32]