IT in Logistics and Maritime Business

Chapter 35

It in Logistics and Maritime Business

Ulla Tapaninen*, Lauri Ojala†, and David Menachof‡

1. Introduction

This chapter deals with contemporary information technology (IT) solutions and applications in logistics, and focuses on their usage in maritime business. The chapter discusses some of the underlying reasons for the pervasive use of IT, and exemplifies some existing solutions on various levels in shipping. More specifically, the chapter is organised under the following sections:

- intra-company systems, applications and uses of IT (operational systems in capacity allocation, tracking and tracing, ERP/ES-based on management level etc.)

- inter-company systems between business operators (exchange of operational data on cargo, shipments, payments etc. on a system-to-system basis using EDI, XML, etc., and relying either on shared software or dedicated (proprietary) systems)

- company-public authority exchange of data (such as to/from trade and transport authorities – port agencies, customs, border/coast guard etc.)

The list is not exclusive, for example various public sector systems, either within or between public bodies are left outside the presentation. One should also realise that these categories are simplified, and that many of the systems will have overlap into the other sections, but are classified as to their main section.

The interesting linkages of IT to Vessel Traffic Service or Management Systems (VTS/VTMIS) and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) of vessels related to IMO’s International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) convention, to safety at sea, or regional (port) development are beyond the scope of this chapter.1, 2

As far as various sectors of maritime business are concerned, liner shipping is perhaps most affected by IT development.3,4 In liner shipping, the service offered has become a commodity, which is transacted in very high quantities with relatively little negotiation between the parties. The increasing logistics or supply chain management (SCM) needs of shippers also underline the need of efficient information management along the whole supply chain.

In industrial shipping, the number of transactions is typically much smaller than in liner shipping, but the operations often require more negotiation between the trading partners, or parties involved in transport operations. Industrial shipping solutions tend to be dedicated and more long-term arrangements with multiple parties.

The maritime business includes a large number of operators both on the seaside and the landside that are, or that could be, involved. This chapter deals mainly with shipping companies within liner and industrial shipping, and port communities. For IT and information flows in (industrial) bulk shipping, see, e.g. Hull.5

Despite the pervasive use of IT and its immense importance in shipping and maritime operations, it has received surprisingly little research coverage in both logistics and supply chain management literature6,7 as well as in maritime economics literature. For example in journals such as Maritime Policy and Management (MPM) and Maritime Economics and Logistics (MEL), only a handful of papers during the past 7–8 years have touched upon the issue, often from the point of view of a specific problem.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Perhaps because of the focus of the textbooks and the legacy of their authors, the most recent maritime economics or shipping textbooks do not address the IT issue as a separate section either.13, 14

As there seems to be an apparent lack of coverage of the issue, this section attempts to provide a short and updated overview of this topic.15 The text tries to avoid excessive technical detail and acronyms that are ubiquitous in this field.

2. It in Logistics and Supply Chain Management

SCM enables the coordinated management of material and information flows throughout the chain from your sources to your customers.16 The US-based Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) provides the following definition of SCM:

“Supply chain management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all logistics management activities. Importantly, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third party service providers, and customers. In essence, supply chain management integrates supply and demand management within and across companies.”17

The supply chain is both a network and a system. The network component involves the connections needed in the flow of products and information. The systemic properties are the interdependence of activities, organisations and processes. As one example, transportation transit times influence the amount of inventory held within the system. Generally said, actions in one part of the system affect other parts.18

Mentzer19 defines a supply chain as a set of three or more companies directly linked by one or more of the upstream and downstream flows of products, services, finances and information. To be supply-chain oriented means that the company consciously develops the strategic system approach to enhance the processes and activities involved in managing the various flows in a supply chain. Supply chain management can envisage almost all of the company’s main functions, or at least those functions like sales, marketing, R&D and forecasting can be handled within a supply chain context. To sum it up, SCM means a systemic coordination of the traditional business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the chain.

Information is an essential part of logistics and supply chains. The flow of information consists of data that is needed to launch the flows of material and capital and to steer them. Information can be generated in three ways: current information, forecasts and historical information. Some logistics models are based on current information. As an example, vehicle dispatching models need information about today’s orders, vehicles available and driver status. Other models are based on forecasts. Historical data is then used to predict future demand, available production capacity, and so on. Some models use actual historical data to calibrate model accuracy. This means that model outputs can be compared to what actually happened to ensure the model is valid.20

Enterprise resource planning is one of the most essential functions in a modern manufacturing company and it also has a very strong supply chain implication. The old MRP-originated model, nowadays running at the core of the most sophisticated ERP systems: “What do I need, what do I have, what do I need to get and when” is right at the backbone of the integrated supply chain. The requirements are taken from a customer or from internal forecasts.21 This has also had a profound effect on the way in which major companies now operate their global manufacturing and supply chains. “Innovative supply chain management structures are rapidly emerging. These incorporate expanded access to ‘e-sources’ of supply, which use web-based exchanges and hubs, interactive trading mechanisms and advanced optimisation and matching algorithms to link customers with suppliers for individual transactions.”22 Many industries have embarked on reengineering efforts to improve the efficiency of their supply chains. The goal of these programs is to better match supply with demand so as to reduce the costs of inventory and stockouts, where potential savings are substantial.

One key initiative is information sharing between partners in a supply chain. Sharing sales information has been viewed as a major strategy to counter the so-called “bull-whip effect”, which is essentially the phenomenon of demand variability amplification along a supply chain. It can create problems for suppliers, such as grossly inaccurate demand forecasts, low capacity utilisation, excessive inventory, and poor customer service.23 The result for many companies is an expanded role of global sourcing of supply, and global reach in the search for customers. This, in turn, signifies an increasingly important role for liner shipping companies in making supply chains more efficient. It is this visibility that today’s IT systems are able to provide.

Trade and transport operations invariably involve numerous partners both in the public and the private sector, such as banking and insurance agents, in addition to various logistics service providers. Likewise, the trading partners (buyers and sellers or consignors and consignees) evaluate the practicalities often on a case-by-case basis.

3. Intra-Company Information Flows

It is not possible to describe all the possible uses of IT for intra-company information purposes, and many of these intra-company systems integrate with intercompany systems. What we will attempt to do is describe some of the systems in place and highlight the key issues that are related to these systems. It should also be noted that the logistics functions must still take place whether or not there is an IT solution available. For example, before ERP programs, accounting data was still maintained, Bills of Materials were still created, sales orders were still processed, but much less efficiently than today.

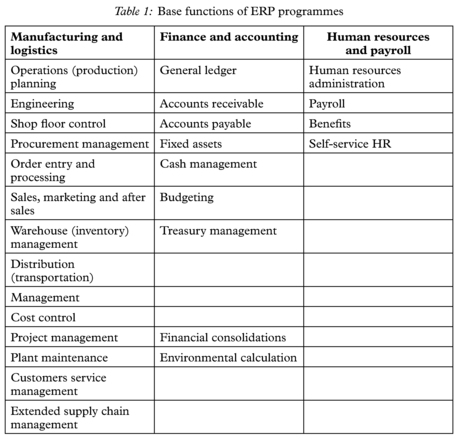

Enterprise Resource Planning programmes are the foundation for many firms’ IT capabilities. Companies like SAP, J.D. Edwards, PeopleSoft, and Oracle are the major companies in this multi-billion dollar industry. All ERP providers are looking to extend the capabilities of their products by adding additional functionality to their product. The three major functional areas of ERP are: Manufacturing & Logistics, Finance & Accounting, and Human Resources & Payroll (see Table 1). Various environmental calculation systems have become a significant part of present-day accounting systems, reporting e.g. CO2 emissions, fuel consumption, amounts of waste and waste water.

Jakovljevic24 identifies some of the key reasons why ERP systems have become so popular and are essential to the modern firm. These are strategic, tactical and technical.

- enable new business strategies;

- enable globalisation;

- enable growth strategies;

- extend supply/demand chain;

- increase customer responsiveness.

Tactical reasons:

- reduce cost/improve productivity;

- increase flexibility;

- integrate business processes;

- integrate acquisitions;

- standardise business processes;

- improve specific business processes/performances.

Technical reasons:

- standardise system/platform;

- improve quality and visibility of information;

- enhance technology infrastructure to handle the immense amount of data.

Programmes that “plug-in” to ERP systems are gaining in popularity, as enhanced functionality not offered by the base ERP system is required to gain competitive advantage.

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) software is designed to keep track of more than just customer orders. Delivery preferences, and past ordering profiles are among some of the information captured by CRM systems.

In addition to ERP, Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) is a commonly used technique in logistics companies. EDI stands for standardised automated transmission of data between two information systems. An example of the use of EDI is transmission of different documents, such as orders, invoices and customs documents. With EDI, these are automatically transmitted from the sender company’s IT system to the receiving company’s information system. The use of EDI is very reasonable when there are large flows of goods and the company’s partners are established. The building of EDI connections is expensive and there has to be quite a large number of transactions for the system to pay itself back. These facts make it unprofitable for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to use EDI.

The versatility of standards can also be considered as a downside of EDI. It is possible that a company is forced to use different kinds of EDI messages with different customers because of the customers’ demands. Some logistics companies have begun to use the open standard Extensible Markup Language (XML) aside EDI. XML is an extensible language, because the user can define the mark-up elements. The purpose of XML is to help information systems share structured data, especially through the Internet, to encode documents, and to serialise data. The main difference between these two is that EDI is designed to serve the needs of business, and is a process, whereas XML is a language.25

Because of the extensive cost in implementing EDI or XML systems SMEs usually make bookings to transportation companies using the company’s own web-based booking systems. The advantage of these systems is a reduction of errors and a decrease in costs, but SMEs may have to book on multiple internet platforms.

After a day of sales orders being generated and shipments organised, companies that have their own delivery fleets must send those vehicles out on the road to deliver to their customers. This is the job of routing and scheduling software, provided by firms such as IBM through ILOG, Radical, ALK Technologies and Paragon. Simple routing and scheduling problems can be solved by Linear Programming (LP) but as the number of constraints grows, the ability to obtain an optimal solution decreases. This is where the complex algorithms used by these specialised programmes come into their own.

In liner shipping companies, where changes of shipping routes are very seldom done, the allocation of vessels on routes is usually done by combining expert knowledge and experience with spreadsheet systems.

In routing problems, the objective is generally to minimise cost subject to constraints such as total travel time, road distance between deliveries, waiting time at each stop, and driver work regulations. Costs are assigned to each type of constraint, and the programme searches for a feasible solution. PCmiler (ALK associates) is just one version of this type of software programme.

Scheduling is a much more complex task, as it must incorporate many more requirements. Routing software generally doesn’t check to see if the total quantities you are trying to ship exceed the capacity of the vehicle. Scheduling looks at total capacities and also looks at additional constraints such as delivery time windows.

Many companies working with just-in-time production facilities need strict delivery times. They cannot take delivery early or later than specified periods, and thus a vehicle that could deliver to all the customers in terms of capacity constraints might be unable to deliver those goods within the time parameters set by the customers. The costs and distance travelled using scheduling constraints is generally higher than when routing only issues are required.

ILOG Solver software from IBM allows a user to integrate shipment data from their ERP system by consolidating all the shipments for a given time period, then using the available fleet information along with the information for all of the shipments, to generate a set of shipping plans to assist in the order of deliveries for each vehicle required to meet all of the constraints. If no feasible solution is found, the user is notified, and will have to make management decisions as to which shipments will be unable to be delivered within their time windows, or must attempt to find additional vehicles that enable a feasible solution to be found.

Warehouse Management Systems are another popular “plug-in” adding enhanced capabilities for inventory control. While ERP systems have some ability to keep inventory storage location data, it is not nearly enough for complex warehouse operations.