Is Access to Essential Medicines as Part of the Fulfillment of the Right to Health Enforceable through the Courts?

Introduction

Issues of human rights affect the relations between the State and the individual; they generate State obligations and individual entitlements. The promotion of human rights is one of the main purposes of the UN. For example, the WHO Constitution of 1946 says that “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.” Article 25.1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) says that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.”

The right to health is also recognized in many other international1–3 and regional4–6 treaties, especially the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) of 1966, an international treaty that is binding on States parties (States that have acceded to, signed, or ratified an international treaty) and provides the foundation for legal obligations under the right to health. In the ICESCR, States parties “recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.” In Article 12.2, the treaty lists several steps to be taken by States parties to achieve the full realisation of this right, including the right to: maternal, child, and reproductive health; healthy natural and workplace environments; prevention, treatment, and control of disease; and “the creation of conditions which would assure to all medical service and medical attention in the event of sickness.” Article 12 thus constitutes an important standard against which to assess the laws, policies, and practices of States parties.

The implementation of the ICESCR is monitored by the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which regularly issues authoritative but non-binding General Comments, which are adopted to assist States in their interpretation of the ICESCR. In General Comment 3, the Committee confirms that States parties have a core obligation to ensure the satisfaction of minimum essential levels of each of the rights outlined in the ICESCR, including essential primary care as described in the Alma-Ata Declaration, which includes the provision of essential medicines.

General Comment 14 of May, 2000, is particularly relevant to access to essential medicines. Here the Committee states that the right to medical services in Article 12.2 (d) of the ICESCR includes the provision of essential drugs “as defined by the WHO Action Programme on Essential Drugs,”7

According to the latest WHO definition, essential medicines are: “those that satisfy the priority health care needs of the population. Essential medicines are selected with due regard to disease prevalence, evidence on efficacy and safety, and comparative cost-effectiveness. Essential medicines are intended to be available within the context of functioning health systems at all times, in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality, and at a price the individual and the community can afford. The implementation of the concept of essential medicines is intended to be flexible and adaptable to many different situations; exactly which medicines are regarded as essential remains a national responsibility.”8

Although the ICESCR acknowledges the limits of available resources and provides for progressive (as opposed to immediate) realisation of the right to medical services, States parties have an immediate obligation to take deliberate and concrete steps towards the full realisation of Article 12, and to guarantee that the right to health will be exercised without discrimination of any kind.

Most countries in the world have acceded to or ratified at least one worldwide or regional covenant or treaty confirming the right to health. For example, more than 150 countries have become State parties to the ICESCR, and 83 have signed regional treaties.9 More than 100 countries have incorporated the right to health in their national constitution.

Some might argue that social, cultural, and economic rights are not enforceable through the courts, and some national courts have indeed been reluctant to intervene in resource allocation decisions of governments. Yet accountability and the possibility of redress are essential components of the rights-based approach. Being a State party to a human rights treaty that is internationally binding creates certain State obligations to its people. Do governments live up to these binding obligations in practice? If not, do individuals manage to obtain their rights? And if they do, which factors have contributed to their success?

This study analyses the question of whether access to essential medicines as part of the fulfilment of the right to health can be enforced through national courts (is justiciable) in low-income and middle-income countries. The study is part of a general attempt by WHO to integrate the promotion and protection of human rights into national policies and to support further mainstreaming of human rights throughout the UN.

Methods

A systematic search was done to identify completed court cases in low-income and middle-income countries in which individuals or groups had claimed access to essential medicines with reference to the right to health in general, or to specific human rights treaties ratified by the government. Six different search methods were used. A general boolean search of the internet was done with variations in the keywords that were linked together (such as human rights, essential drugs, access to medicines). An email survey was sent to a group of the most prominent nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) working on the right to medicines that were noted from the internet search. The email requested assistance in finding information on cases, to which the Lawyers Collective in India responded with information. The following legal databases were accessed and searched: LexisNexis, Natlex, Ohada, Portal Droit Francophonie, CSA Illumina, Electronic Information System for International Law, Westlaw database, Eurolex, and the Legal Information Institute. Other databases consulted were The Economic, Social and Cultural Rights database on the internet ESCR-NET, the Asian Legal Resource Centre database, the AllAfrica database, the European Court of Human Rights database (HUDOC), the International Commission of Jurists website, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and reports from the UN Human Rights regional offices. Individual country searches were done for all low-income and middle-income signatories to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The World Legal Information Institute was used to locate each country’s online national jurisprudence database. A further specific internet search was done on countries without any online national jurisprudence database, focusing on the country name and the search terms; this method considered each country in a thorough and systematic way.

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

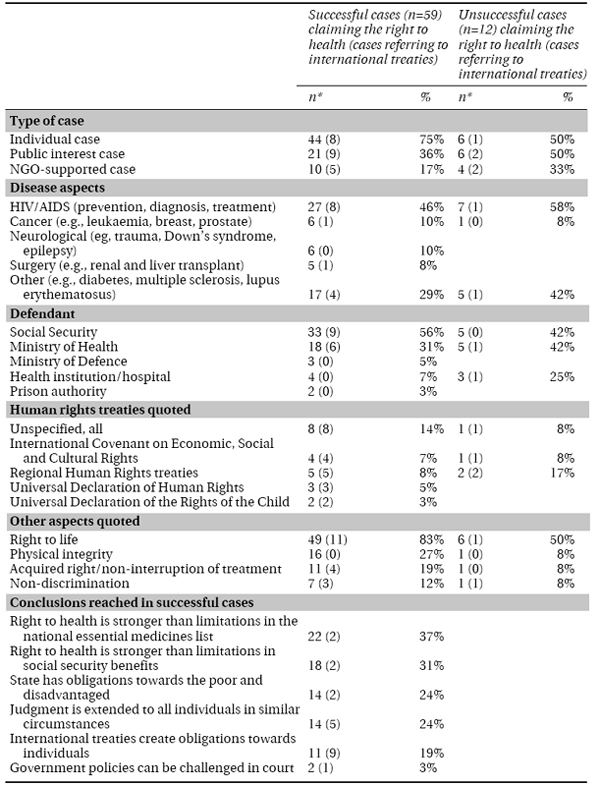

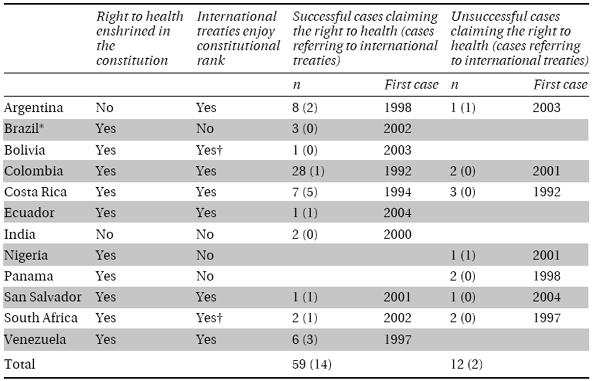

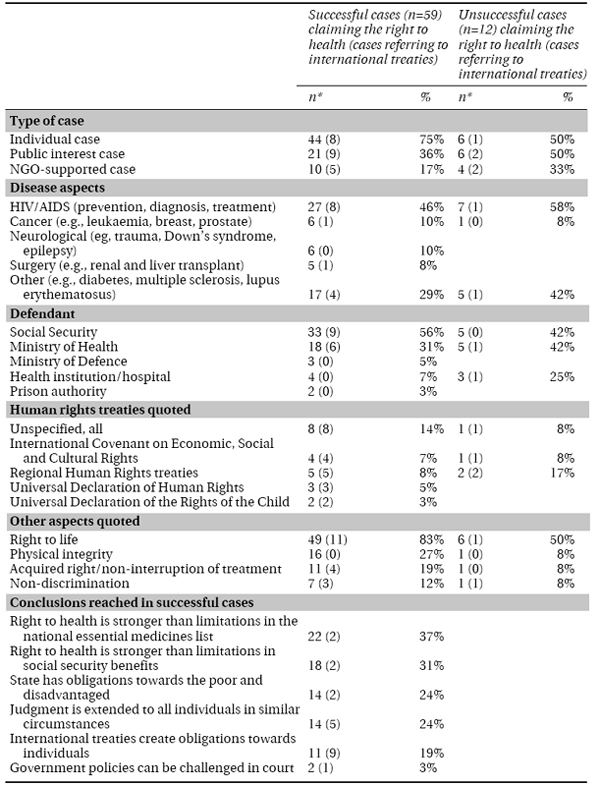

The systematic search identified 73 cases from 12 low-income and middle-income countries. In five cases, only a brief summary of the judgment was available. In three of these cases, information was still sufficient to include them in the analysis. The full analysis is therefore based on 71 cases, of which 59 were won and 12 were lost (Table 9.1). Of the cases included in the analysis, 14 successful and two unsuccessful cases specifically referred to one or more international human rights treaties signed by the government. The main characteristics of the cases are shown in Table 9.2. Arguments used in the unsuccessful cases are shown in Table 9.3. Full references and summary information for each case are available from the authors on request.

Table 9.1 Number of court cases per country

* Large number of new cases filed more recently. † Status not fully clear.

* Characteristics are not mutually exclusive.

Table 9.3 Main arguments quoted in unsuccessful cases (n = 12)

n (%) | Country | |

National list of essential medicines upheld | 4 (33%) | Argentina*, Colombia, Panama, South Africa |

The medicine claimed was the wrong choice, lack of evidence on efficacy, or no need | 3 (25%) | Costa Rica (2×), El Salvador |

The medicine had been supplied in the mean time | 2 (17%) | Colombia, Costa Rica |

Court of Law not ready to decide on policy issues | 1 (8%) | South Africa |

Case dismissed on technical grounds | 1 (8%) | Panama |

Court refuses to hear the plaintiff because of fear of HIV infection | 1 (8%) | Nigeria* |

* Cases referring to international treaties signed by the government.

Of the 12 countries in which court cases were identified, 11 are State parties to the ICESCR; South Africa has signed but not ratified the ICESCR. In all countries except Argentina and India, the right to health is recognized in the constitution. In six countries the constitution includes a provision that international treaties signed by the State have constitutional rank, override domestic laws in case of conflict, or both (Table 9.1).

More than 90% of cases are from nine countries in Central and Latin America.

Between 1991 and 1997, three countries (Colombia, Costa Rica, and Venezuela) had their first successful case; in the 7 years from 1998 to 2004 there were the first successful cases in seven other countries, including countries outside the Americas (South Africa and India). Most cases (50 cases, 70%) were individual; 27 (38%) were public interest cases, and 14 (20%) were supported by NGOs. In 61 (86%) cases the Social Security system or the Ministry of Health were the defendants. About half the cases related to potentially life-saving treatment of HIV/AIDS.

Discussion

This study has shown that access to essential medicines as part of the fulfilment of the right to health could indeed be enforced through the courts in several low-income and middle-income countries, with most of the experience to date coming from Central and Latin America. The most important success factor has been that certain rights are enshrined in the national constitution. Key constitutional provisions seem to be those on the right to health and on defined State obligations with regard to health care services and social welfare. Human rights treaties ratified by the government have probably supported the creation of such constitutional provisions in the first place. When referred to in the courts they have usually provided additional force to such constitutional obligations, especially in the presence of a constitutional provision that international treaties supersede domestic law. One case in Argentina shows that international human rights treaties can also successfully be invoked in the absence of a constitutional right to health. In 80% of cases, the right to health was linked to the right to life. Most negative rulings were based on a recognition of the limitations specified in the national essential medicines list or social security benefits, although some courts also made their own analysis of the medical merits of the claim.

Our study has two limitations. First, the fact that most cases were seen in Central and Latin America (despite intensive and targeted efforts to identify cases from other regions) suggests that the observations and conclusions are probably more relevant in this region than in the rest of the world. A possible explanation for this finding is that social security is much more developed in the Americas than in Africa and Asia, where most health care is paid for directly by the patient. Other reasons could be more developed legal systems and higher consumer expectations in the Americas. The second limitation is that adding up the arguments used in different cases from different countries might create a false sense of statistical probability that similar arguments could work in future cases in other countries. This assumption is of course not true, since each current and future case must be judged on its individual merits and within its national legal situation. Yet cases such as the ones reported here contribute to a worldwide body of jurisprudence, which might support further developments in this area. Within these two limitations, the intended value of our analysis is to present a first overview of the situation and to generate some ideas for further analysis and study.

A successful case is defined as one that has led to new, continued, or expanded access to one or more essential medicines for an individual or group. Constitutional provisions probably contributed most to successful outcomes. All countries except Argentina and India include the right to health in their constitution. In nearly all cases, this includes a definition of State obligations with regard to health care services and social welfare. In all countries except Panama and Nigeria, one or more court rulings confirm that these constitutional rights are indeed enforceable (Table 9.1). In six countries (Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Venezuela), international treaties enjoy constitutional rank, and domestic laws should follow international treaties.