Introductory Topics

Revision objectives

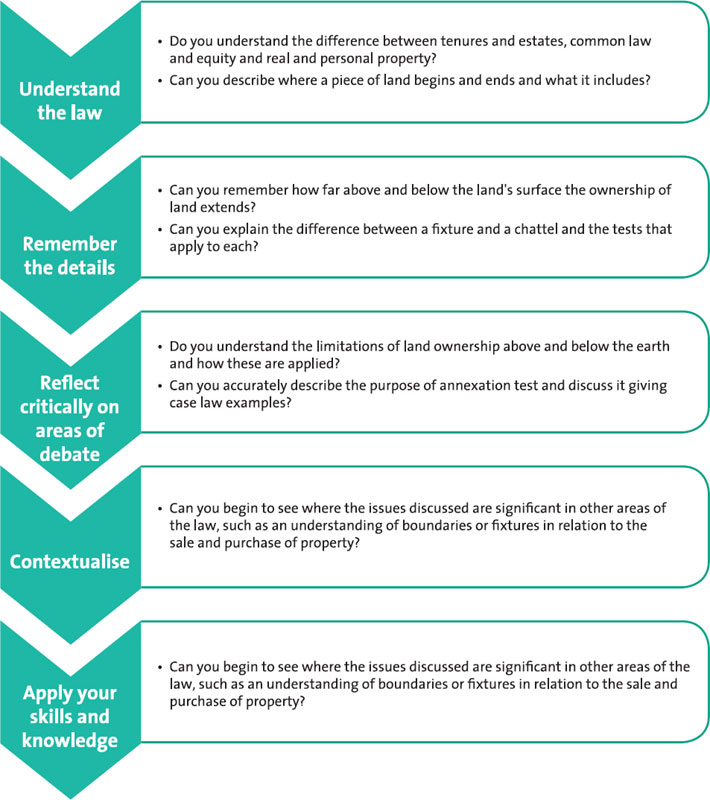

This chapter is designed to introduce a series of closely related but individual introductory topics all designed to answer the same question: what is land? Firstly, the brief history of land law in England and Wales and an explanation of the development of the courts of the common law and equity together provide a picture of what it means to own land in England and Wales, and the dual nature of that ownership. The explanation of real and personal rights in land then shows us the nature of the rights which attach to it. And finally the bulk of the chapter deals with how land is defined in a legal context and what is included or excluded on a sale and purchase.

Aim Higher

As you work through the chapter, consider how these introductory sections relate to other topics in land law, such as formalities for the sale of land, co-ownership and trusts of land. This will help your understanding of these and other topics and how they interact. For example, if a contract for the sale and purchase of land does not give an adequate description of the property, then knowledge of the law of fixtures will be vital in the event of a dispute over what is included in the sale.

History of land law: the 1925 legislation

Introduction

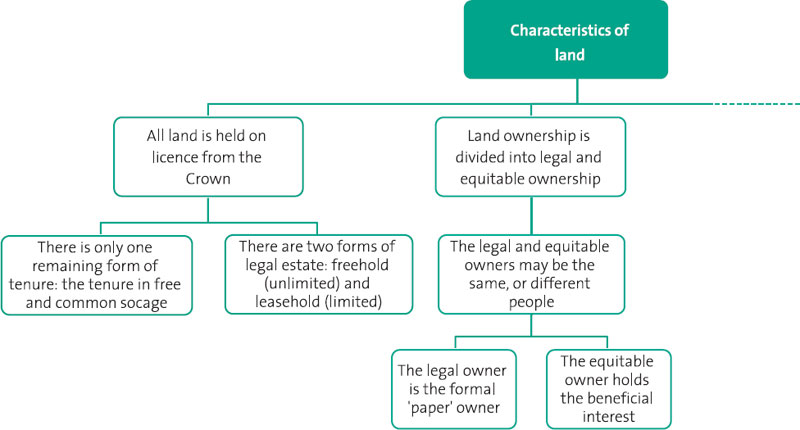

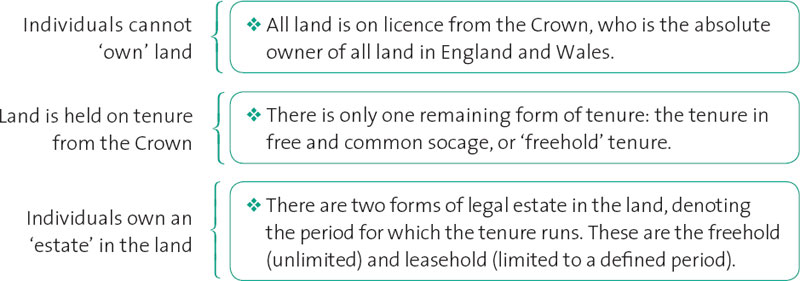

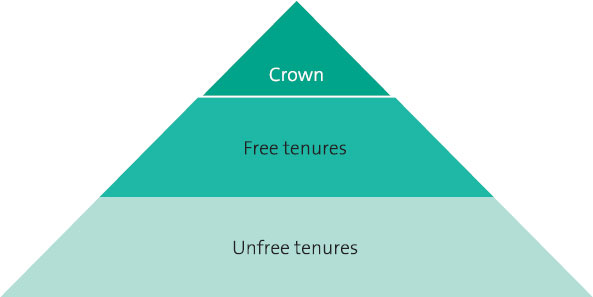

The history of modern land law begins with the Norman Conquest in 1066. When William the Conqueror invaded Britain, he brought with him a new system of landholding which to this day still forms the building blocks on which modern land law in England and Wales is based. All land was in the ownership of the king, who then granted rights to use the land, known as tenures, to those he favoured.

All land was in the ownership of the king.

In turn, lesser tenures would be granted by those holding the land to others to farm it. This process could be repeated a number of times, until a chain of landholding was created, starting with the king, as absolute owner of the land, stretching down to the most lowly peasant, who had simple rights to occupy the land in return for working the land on behalf of their immediate lord.

Although in reality they were many and diverse in nature, broadly speaking these tenures could be divided into two kinds: free tenures, which were more like land management roles and which did not require any form of menial labour, and unfree, or copyhold tenures, which required the landholder to actually farm the land.

Common Pitfalls

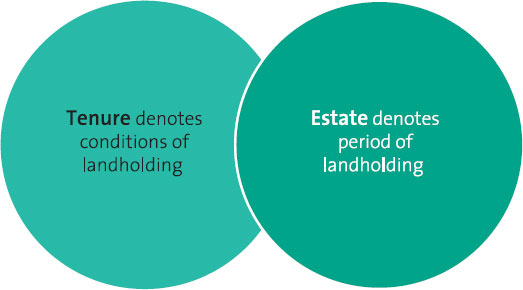

The terms ‘tenure’ and ‘estate’ are often used interchangeably, but this is incorrect as the terms refer to two quite different things: the tenure of the land describes the basis on which the land is held (i.e. what conditions apply to the landholding, if any); the estate is the period for which the tenure is held, which may be either unlimited (freehold) or limited to a fixed period of time (as with a lease).

The system was a good one in that all land was held on licence from the Crown and the king, as absolute owner of the land, maintained ultimate control of all the land over which he presided. However, the system was not without its flaws. The granting of numerous and successive tenures over a period of time resulted in the existence of a vast, multi-layered framework of property ownership which was in dire need of simplification.

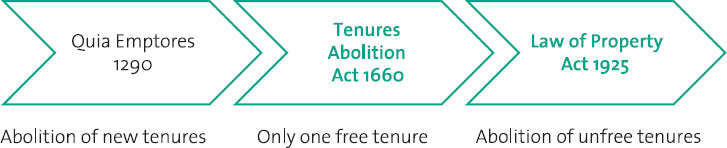

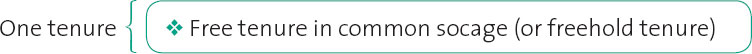

As a first step towards this in 1290 an early form of statute known as the Quia Emptores outlawed the creation of new tenures by anyone other than the Crown. This prevented any further subdivision of the land, but did nothing to simplify the existing system of landholding. In fact, it was not until the Tenures Abolition Act in 1660 that any progress was made in this respect, by converting any existing freehold tenures into a single kind of tenure: the freehold in ‘common socage’. This still left numerous forms of unfree tenure, however, and these were not abolished for a further 250 years, with the advent of the Law of Property Act 1925.

The 1925 reforms and the doctrine of estates

The abolition of unfree tenures was not the only amendment to the process of land law of England and Wales made in 1925. In fact, the Law of Property Act 1925 was one of a series of six statutes enacted in this year. These were:

The Law of Property Act 1925 |

The Trustee Act 1925 |

The Land Registration Act 1925 |

The Settled Land Act 1925 |

The Administration of Estates Act 1925 |

The Land Charges Act 1925 |

The Acts brought about a number of sweeping changes, albeit that the Law of Property Act is the most significant for the undergraduate study of land law.

As well as reducing the number of tenures to one, the Law of Property Act 1925 also reduced the number of legal estates in land. Estates are different from tenures in that, whereas the tenure of the land, historically, describes the terms on which the property is held, the estate in the land describes the length of time for which that tenure exists. An estate can therefore be said to be a right to use land for a certain time.

As with tenures, before the advent of the Law of Property Act 1925, there were a number of different kinds of estate in land. However, these have now been reduced to two remaining estates: the ‘fee simple absolute in possession’ (or freehold) and the ‘term of years absolute’ (or leasehold).

A freehold denotes the right to hold the land for an unlimited period of time which will come to an end only on the death of the landholder in the absence of a valid will or living relatives; a leasehold denotes the right to hold the land for a limited period of time, after which it will revert to the freeholder.

Points to remember about tenures and estates:

Understanding: legal and equitable rights in land

The division between law and equity

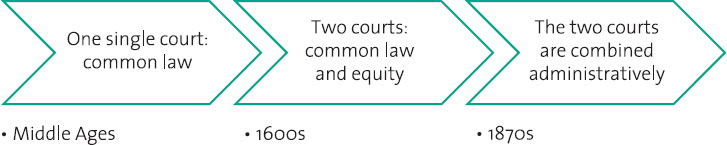

The legal system in England and Wales is unique in that it is separated into two distinct parts: law and equity. The reason for this is historic. During the Middle Ages there was only one court, which was the court of the common law. In this court, judges applied the law of the kingdom strictly in accordance with precedent. This strict application of legal rules made the common law harsh and unbending, and so it became commonplace for parties who did not agree with the judgments handed down to appeal directly to the king for justice.

Common law | Equity |

|

|

The king passed these applications on to his secretariat to administer, with such success that by the 1600s the secretariat was recognised formally as a court with its own judicial power. This was the birth of the court of equity. Whereas the court of the common law dealt with strict matters of law, the court of equity handed down their judgments on the principles of fairness or conscience.

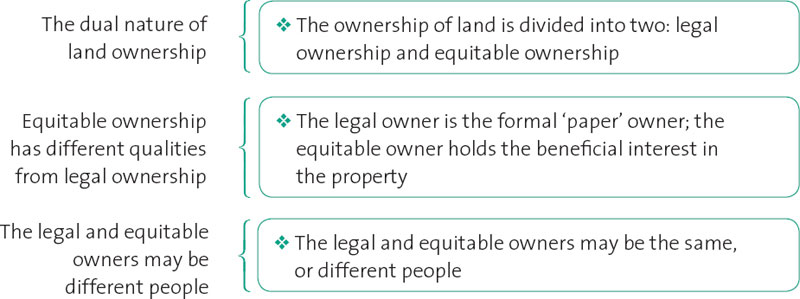

Legal and equitable ownership of land

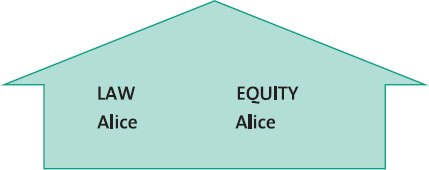

As a result of this dual system of law, it is commonplace to divide land ownership itself into two constituent parts: legal and equitable. The qualities attributable to these two types of land ownership mirror the principles of law and equity; so, whereas the legal ownership of the property refers to the formal, paper ownership of the property, denoting the person with the right to deal with the land at common law and including the right to dispose of it, equitable ownership denotes the beneficial rights in the property, including the right to live in it or to make money from it, either through sale or rental.

Legal ownership | Equitable ownership |

|

|

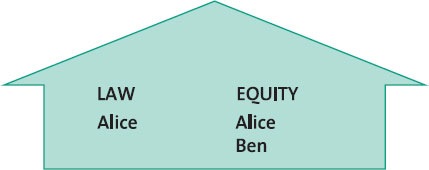

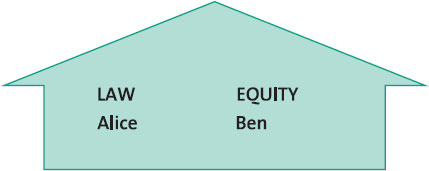

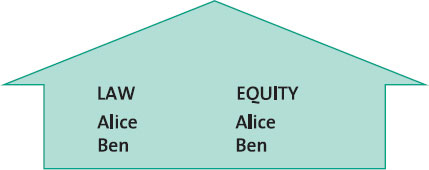

The legal and equitable ownership of property can be held either by a single person or by two or more different people. In the case of a single legal owner, they can simply hold the whole of the legal and equitable interest in the property for themselves:

Or they can hold the property for the benefit of themselves and another:

Or they can simply hold the legal title to the property on trust for the benefit of a third party in equity:

Where there is multiple ownership but the legal and equitable property owners are the same people, this division of the legal and equitable ownership of the land is achieved automatically under statute. Under s 36 of the Law of Property Act 1925 a trust of land is imposed, whereby the legal owners of the property are viewed as holding the legal title at law on trust for the benefit of themselves in equity.

Co-ownership issues will be dealt with in more detail in Chapter 5.

Points to remember about law and equity

The proprietary nature of land: real and personal property

Introduction

One more aspect of land as a form of property that makes it unique is that it is subject to its own special treatment by the courts.

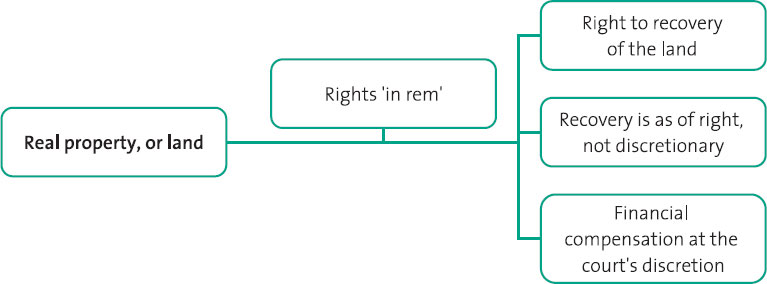

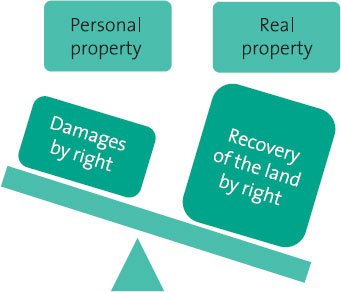

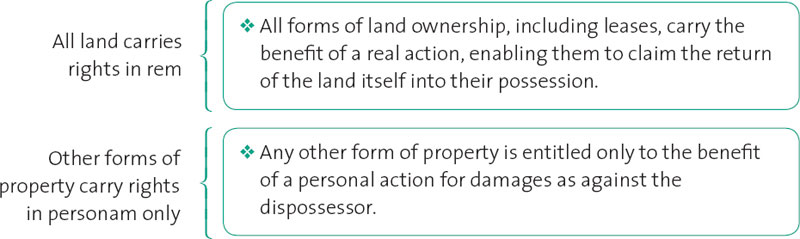

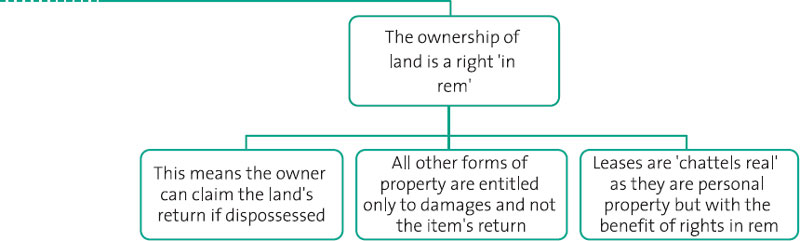

Whereas all other types of property, including large items such as cars and boats, and smaller items such as laptops, phones etc., have the benefit only of a right ‘in personam’, or personal action, land has the benefit of a right ‘in rem’, or real action. The difference between the two is significant.

Personal property

If someone takes your personal property from you, you have the right to seek financial compensation for its loss through the courts against the person who has taken it. You have no right to seek the item’s return, however, although the court may choose to order the return of the item if this is still possible. This limited right is known as a right ‘in personam’ and property which benefits from this right is known as personal property, or chattels.

Real property

If a third party dispossesses you of your land, on the other hand, you are entitled as of right to make a claim through the courts for that land to be returned to you. This right is known as a right ‘in rem’, and property that benefits from this right is known as real property.

Chattels real

Leases are given their own special form of categorisation, separate from freehold land. The reason for this is that the basis of a lease is formed in contract and the benefit of a contract is deemed a form of personal property by the courts. Therefore, although we study them in the context of land law and they are recognised as one of the two legal estates in land under the Law of Property Act 1925, their basic definition has historically been that of a chattel.

Despite this, the significance of the lease as conveying legal rights over land has led them to attract the same benefits as freehold land. This means that, if a tenant under a lease is dispossessed of his leasehold property, he can apply to the court for the return of that land under a real action. Leases can therefore be categorised as chattels real: that is, personal property with the benefit of a real action.

Points to remember about real and personal property

Understanding: the definition of land

Introduction

The legal definition of land is set out in the Law of Property Act 1925, at s 205(1)(ix).

Section 205(1)(ix)

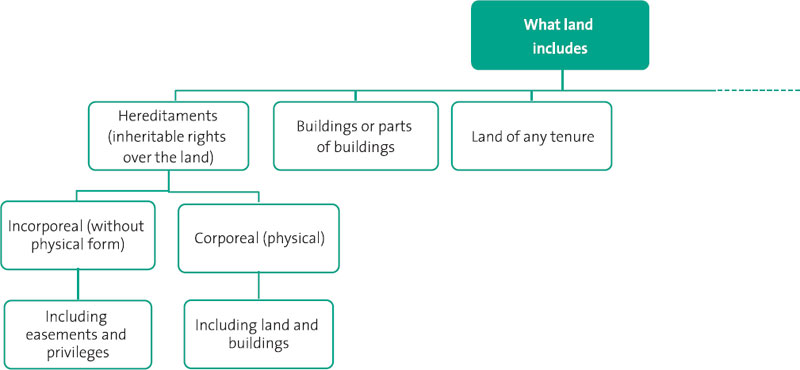

‘Land’ includes land of any tenure, and mines and minerals, whether or not held apart from the surface, buildings or parts of buildings (whether the division is horizontal, vertical or made in any other way) and other corporeal hereditaments … incorporeal hereditaments, and an easement, right, privilege, or benefit in, over, or derived from land.

Land of any tenure

As all land is held on tenure from the Crown, the definition therefore includes all land.

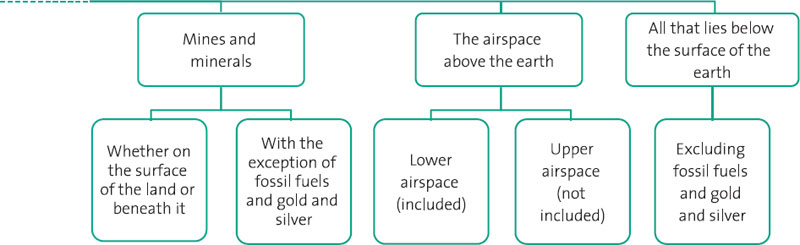

Mines and minerals

The statutory definition states that land includes any mines dug or existing under the surface of the land and any minerals found, whether they are discovered under the ground or on its surface, and regardless of whether or not they are physically attached to the surface of the land.

However, it should be noted that there are certain kinds of minerals that are actually excluded from private ownership. These are:

Gold and silver |

Fossil fuels |

Such minerals belong to the Crown and the State respectively and cannot be privately owned.

Buildings

The statute also tells us that land includes any building or part of a building which stands on it.

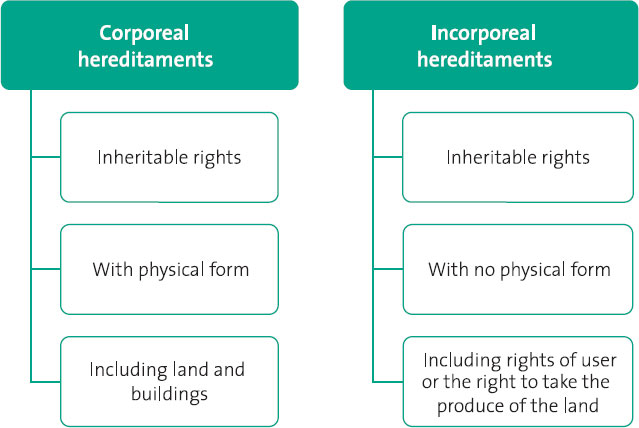

Corporeal and incorporeal hereditaments

A hereditament is a something that can be inherited. Corporeal hereditaments have physical form, and as such include the land itself and anything built on it. Incorporeal hereditaments are rights over the land that have no physical form. These include the items listed in the statutory definition, like an easement, which is a right of user such as a right of way, or a privilege, which is a right to take something from the land, such as the right to fish.

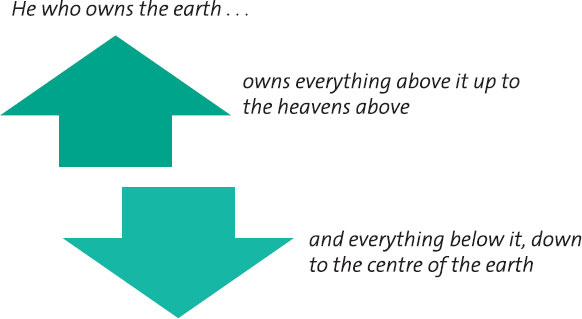

Land above and below the surface

The legal definition of land is quite extensive but, with the exception of a brief mention of mines and minerals below the surface of the earth, does not specifically deal with the subsoil reaching below the land or the airspace above it. In order to get a full definition of land therefore, we need to look to the common law that predates the statute. This says that a person who owns the earth owns everything above it and everything below it down to the centre of the earth.

Land below the surface of the earth

The courts construe the rule strictly, as can be seen in the leading case of Grigsby v Melville [1974], below.

Case precedent – Grigsby v Melville [1974] 1 WLR 80

Facts: A cellar existed under the claimant’s property, accessible only from the neighbouring property. When the claimant discovered the existence of the cellar, they sued the defendant for trespass. The court found in favour of the claimant.

Principle: A person who purchases land acquires everything that lies below its surface.

Application: In a problem question scenario, use this case to support your argument that the person who owns land also owns everything below it, down to the centre of the earth. Remember that this is irrespective of the means of access.

Aim Higher

In a problem question scenario, do not forget that, whilst the owner of the land theoretically owns everything down to the centre of the earth, including mines and minerals (as set out in s 205), this is subject to the caveat that certain mines and minerals are owned by the State. An examiner will expect you to apply this to your problem question, where appropriate.

Designed to uphold the law of the kingdom

Designed to uphold the law of the kingdom Rigid and based on precedent

Rigid and based on precedent A court of conscience

A court of conscience Designed to apply justice where the strict application of common law rules resulted in an unfair outcome

Designed to apply justice where the strict application of common law rules resulted in an unfair outcome Refers to the formal, paper ownership of the property

Refers to the formal, paper ownership of the property Gives the owner the right to deal with the property at law

Gives the owner the right to deal with the property at law Refers to the beneficial rights of the individual in the property

Refers to the beneficial rights of the individual in the property Gives the owner the right to live in the property or to receive income from it

Gives the owner the right to live in the property or to receive income from it