INTRODUCTION TO COMPANY LAW

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should understand:

The scope of ‘company law’

The scope of ‘company law’

The relationship between core company law, insolvency law, securities regulation and corporate governance

The relationship between core company law, insolvency law, securities regulation and corporate governance

The sources of company law

The sources of company law

The importance in the study of company law of foundation course legal knowledge and skills

The importance in the study of company law of foundation course legal knowledge and skills

The historical development of the registered company and its statutory framework

The historical development of the registered company and its statutory framework

The arguments for and against limited liability

The arguments for and against limited liability

The influence of the European Union on UK company law

The influence of the European Union on UK company law

The rationale behind the Companies Act 2006 and subsequent developments

The rationale behind the Companies Act 2006 and subsequent developments

This book is written primarily for undergraduate law students studying company law. It aims to guide students to an understanding of:

the scope of company law and how it is linked to other specialist legal subjects such as securities regulation and insolvency law;

the scope of company law and how it is linked to other specialist legal subjects such as securities regulation and insolvency law;

the sources of company law;

the sources of company law;

key legal principles of company law;

key legal principles of company law;

key moot, or unsettled, issues in company law.

key moot, or unsettled, issues in company law.

It is also written to assist students to develop their ability to:

understand and appreciate the context in which company law operates;

understand and appreciate the context in which company law operates;

apply key principles of company law to solve problem questions;

apply key principles of company law to solve problem questions;

interpret legislation;

interpret legislation;

use precedents to construct logical and persuasive arguments and discuss moot points of law;

use precedents to construct logical and persuasive arguments and discuss moot points of law;

think reflectively and critically about the strengths, shortcomings and implications of various aspects of company law.

think reflectively and critically about the strengths, shortcomings and implications of various aspects of company law.

Company law and company law scholarship have grown rapidly in volume in recent years making it unrealistic to cover the whole of even ‘core’ company law (a term explained in the next section) in what is usually little more than two terms if students are to achieve understanding rather than acquire a superficial level of knowledge. Three filters commonly used to limit the volume of material covered are adopted in this book, which focuses on:

companies formed to run businesses for profit, not companies formed for charitable or other non profit-making purposes;

companies formed to run businesses for profit, not companies formed for charitable or other non profit-making purposes;

registered limited liability companies with a share capital rather than other types of registered company such as unlimited companies or companies limited by guarantee;

registered limited liability companies with a share capital rather than other types of registered company such as unlimited companies or companies limited by guarantee;

the Companies Act 2006, with limited coverage of securities regulation (also known as capital markets law or financial services law) or insolvency law.

the Companies Act 2006, with limited coverage of securities regulation (also known as capital markets law or financial services law) or insolvency law.

Whilst students choose to study company law for a number of reasons, all share the aim of successfully completing their assessment(s). The activities and sample essay questions in each chapter of this book are designed to help you to test your knowledge and understanding and develop a successful approach to answering company law questions.

core company law

The law governing the creation and operation of registered companies

1.2 What we mean by ‘company law’

The focus of this book is what is sometimes referred to as ‘core company law’, which is essentially the law governing the creation and operation of registered companies. It is very easy to identify core company law today as it is almost all contained in the 1,300 sections and 16 schedules of the Companies Act 2006, regulations made pursuant to that Act, and cases clarifying the application of the statutory rules and principles.

That said, the Companies Act 2006 is not a comprehensive code of core company law in the sense of a body of rules that has replaced all common law rules and equitable principles previously found in cases. Certain aspects of core company law, such as remedies available for breach of directors’ duties, remain case-stated law distinct from statute law and many cases interpreting provisions of past Companies Acts remain relevant today. The Companies Act 2006 is also not the only current statute containing core company law. Key relevant statutes and the role of case law in core company law are considered in section 1.3 under the heading ‘Sources of company law’.

Limits of core company law

A more comprehensive review of law relevant to companies would include insolvency law and securities regulation (the latter is part of a larger body of law known as capital markets law or financial services law) to the extent that they apply to companies. In the last 25 to 30 years, each of these areas of law has become a highly developed and voluminous legal subject in its own right. Realistically, not even the parts of each relevant to companies can be covered in any depth in a company law textbook of moderate length and no attempt is made here to do so. Students interested in those subjects specifically can find references to texts providing a good starting point for their studies at the end of this chapter.

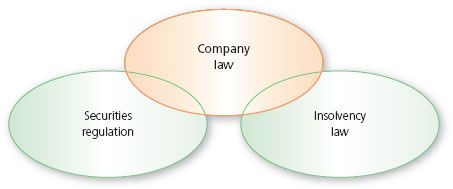

Figure 1.1 Company law includes parts of securities regulation and insolvency law.

Corporate governance has also emerged as a subject of study in its own right over the last 25 to 30 years, so much so that it is appropriate to say a few words about it in the context of setting out what we mean by core company law. Corporate governance is not a legal term, rather, it is a label, or heading under which the questions how, by whom and to what end corporate decisions are or should be taken, are analysed and reflected upon. Issues such as the role law plays and how far the law can and should be used to achieve effective or good corporate governance arise as part of those analyses and reflections.

Those who support extensive use of law and regulation backed up by law to achieve effective corporate governance are said to support the ‘juridification’ of corporate governance, those against include those who are said to prefer ‘private ordering’. Core company law and corporate governance overlap to the extent that a large part of core company law is a body of rules and principles establishing how and by whom corporate decisions may lawfully be made or are legally required to be made.

Core company law textbooks differ in the extent to which they deal with insolvency law, securities regulation and corporate governance. The approach taken in this book to each is set out in the following three sections.

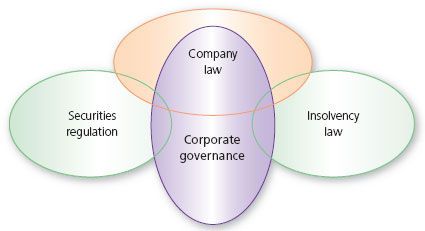

Figure 1.2 Corporate governance.

Even though in theory they could, companies do not tend to continue in existence forever. They either outlive their usefulness or become financially unviable. Before a company ceases to exist, or is ‘dissolved’, to use the legal term, its ongoing operations are brought to an end, its assets are sold and the proceeds of sale are used to pay those to whom it owes money. This process is called ‘winding up’ or ‘liquidating’ the company.

Some companies that are wound up or liquidated are able to pay all their debts in full, that is, they are ‘solvent’, yet the law governing winding up of solvent companies is set out in the Insolvency Act 1986 (and rules made pursuant to that Act, the most important of which are the Insolvency Rules 1986). The explanation for this is that most winding ups involve insolvent companies and when, in the mid-1980s, the law governing insolvent company winding ups was moved out of company law legislation into specific insolvency legislation, it made sense to deal with solvent winding ups in the same statute. This avoided the need for duplication of those winding-up provisions relevant to both solvent and insolvent companies in both the Companies Act 1985 (now replaced by the Companies Act 2006) and the Insolvency Act 1986.

Note that insolvency is a term relevant to both companies and individuals but in the UK the term bankruptcy is used only to refer to the insolvency of individuals, not companies. It is legally incorrect to refer to a company going bankrupt.

Insolvency law is a highly detailed and specialised area of legal practice requiring study of specialist texts for a full understanding of its scope and complexity. That said, the two key formal processes forming the core of insolvency law are administration (a process designed to facilitate the rescue of financially troubled companies) and liquidation (the process by which companies are wound up). Administration is outlined in Chapter 15 and liquidation is examined in Chapter 16.

During the administration and liquidation processes, administrators and liquidators have various powers, including powers to bring legal actions and to review and challenge the validity of certain transactions entered into by the company. Clearly, it is important for anybody seeking to understand the rights of those who deal with companies and the law governing directors (because many of these legal actions and transactions involve directors), to have a basic understanding of these powers. For this reason the relevant provisions of the Insolvency Act 1986 are included in Chapter 16.

Finally, in the case of a winding up, once the assets of the company have been turned into money and any and all contributions secured, the liquidator is required to follow a statutory order of distribution which determines the priority of payment of different types of creditors. Given the significance of this statutory ordering to the decision whether or not to deal with a company, and the terms on which to do so, the statutory order of distribution on liquidation is also covered in Chapter 16.

It is difficult to decide which, if any, part of securities regulation to include in a core company law textbook. The aim of securities law is essentially to provide protections to those who decide to invest their money in securities. The term ‘securities’ covers a complex range of investment products, including products unrelated to companies. A student of core company law is concerned only with securities taking the form of shares and corporate bonds.

Securities regulation is part of what is often called finance law. For our purposes, finance law can be viewed as made up of three parts: banking law; the regulation of those who conduct investment business and the markets on which investments are traded; and, increasingly, the regulation of companies whose securities (shares and bonds) are offered to the public.

Consequently, basically, securities regulation is only relevant to those companies with shares or bonds traded or ‘listed’, i.e. bought and sold, on stock exchanges. As only a very small minority of UK companies have shares or bonds that are traded/listed, it is very important to appreciate that it is a very small number of companies that need to engage with and comply with securities regulation. Securities regulation does not apply to over 99 per cent of registered companies.

Regulatory shortcomings highlighted by the global financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath have resulted in extensive, ongoing reform of finance law globally. Reform of UK law is the result of both UK and EU initiatives. Most of the changes relate to the regulation of banks and the re-alignment of regulatory responsibilities. Re-alignment has been effected by the Financial Services Act 2012. The Financial Services Authority (FSA), as such, has been abolished and its functions have been split between two new regulatory bodies. A new ‘macro-prudential authority’ has been established, called the Financial Policy Committee (FPC), and the two key regulators sitting underneath this umbrella body are the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), which is a subsidiary of the Bank of England, and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

The key securities regulator (the successor to the FSA) is the FCA. Fortunately, apart from this change of regulator, the framework of securities regulation has remained intact. Arguably, the FSA has simply been renamed and refocused, with some of its functions having been removed and given to the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA)

The key securities regulation statute in the UK remains the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), as amended (most recently by the Financial Services Act 2012). The 2000 Act established and empowered the main securities regulator to make detailed provisions governing securities. Those detailed provisions can be found in what is now the Financial Conduct Authority Handbook (FCA Handbook).

The heart of securities regulation is disclosure of accurate information. This theme has been reinforced and supplemented in recent years, in no small part because securities regulation is being used to implement legal initiatives to achieve effective or good corporate governance, which is seen as supportive of efficient capital markets and essential to achieve economic growth. This trend is part of the juridification of corporate governance referred to above. It also causes lawyers to rethink what they mean when they use the terms law and regulation.

Focusing for a moment on the sources of securities regulation, statutory provisions in the FSMA are supplemented by detailed provisions made by the FCA pursuant to powers under the FSMA (the FCA Handbook). This clearly legal regime is supplemented by what is increasingly referred to as ‘soft law’, important examples of which are the UK Corporate Governance Code and the Stewardship Code.

Disclosure of information by companies is provided for both by the Companies Act 2006 and by securities regulation. Accordingly, Chapter 17, which deals with transparency, ventures into securities regulation so that students have an idea of how the securities regulation framework of disclosure for traded/listed companies supplements the Companies Act provisions. Accurate information disclosure is particularly important when shares are being offered to the public for the first time and, for this reason, the corresponding part of securities regulation, the Prospectus Rules, are outlined in Chapter 7.

corporate governance

The system by which companies are directed and controlled

Corporate governance means different things to different people in different contexts. Whenever the term is used, the first question to ask is, in what sense is it being used by the writer? If this is not made clear, it is usually helpful to examine the context in which the term is being used (see also section 9.5 of Chapter 9). Subject to this caveat, two definitions of corporate governance are often referenced (as, for example, in the European Commission Green Paper, ‘The EU Corporate Governance Framework’ (COM(2011) 164 final).

The first is a definition laid down in 1992 in the Report of the Cadbury Committee, a Committee established by the Financial Reporting Council, the London Stock Exchange and the accountancy profession to consider the financial aspects of corporate governance. According to the Cadbury Committee (at para 2.5), ‘Corporate Governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled.’

The second definition is that first provided by the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1999 and repeated in 2004 in the preamble to its revised Principles of Corporate Governance (which principles are subject to a 2014 review) in which corporate governance is identified as one key element in improving economic efficiency and growth as well as enhancing investor confidence.

QUOTATION

‘Corporate governance involves a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders and other stakeholders. Corporate governance also provides the structure through which the objectives of the company are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined.’

‘OECD Principles of Corporate Governance’ (2004) at p. 11

These definitions were crafted in the context of exercises focused on publicly traded (or listed) companies. They were developed with large companies, or groups of companies under common control/governance, and investor/manager conflict forefront in the minds of the drafters. Before turning to the concept of corporate governance in such contexts, and, in particular, the problem of reconciling shareholder primacy and corporate social and environmental responsibility, it is instructive to recall that, as mentioned earlier, most companies are not publicly traded. Most companies are micro, small or medium-sized entities (SMEs) (this term is explained in more detail in section 2.2.2). To date, in the SME context, core company law has been (and largely remains) the alpha and omega of corporate governance.

Corporate governance and small companies

The vast majority of independent companies, that is, companies that are neither part of a larger corporate group of companies nor have shares that are publicly traded, are managed and governed by individuals who own the whole, or a large block of the company’s shares. Additional shareholders are typically related to the majority owner or participate in running the company alongside the majority owner, and it is not uncommon for them to be relatives, co-managers and governors. Most of these companies are not large and are registered as private rather than public companies. Questions about how such companies are governed usually arise out of one of two types of dispute.

The first type of dispute is between majority and minority shareholders. It raises the question whether the director(s) (who is/are the majority shareholder) can behave, or cause the company to behave (i.e. can the company be governed?), in a manner objectionable to, and inconsistent with the interests of its minority shareholders. The second type of dispute is between the company and its creditors. It raises the question whether or not the director(s) (who is/are the shareholders) can behave, or cause the company to behave (i.e. can the company be governed?), in a manner that undermines the ability of the company to pay its creditors.

Whilst other groups, such as employees, suppliers and customers, may be affected by the manner in which a small company is governed, such impacts are typically either relatively minor or can be worked around because these other groups are not really ‘stakeholders’. The size of a small company’s operations means that members of these groups can turn to other companies. Also, self-interested action by managers or directors of small companies is not generally an issue because the manager/directors own the company. To the extent that the managers/directors do not own all of the shares, their pursuit of self-interest raises issues not only, or even mainly, of how to prevent abuse of the powers of directors, but rather, of the legal constraints that exist, or should be imposed, on majority shareholders who seek to operate the company for their own gain rather than for the benefit of all of the company’s shareholders.

Company laws important to regulating small company governance include obvious topics such as directors’ duties and disclosure obligations. However, as the preceding paragraphs suggests, key to small company governance are legal constraints on majority shareholders and remedies available to minority shareholders confronted with majority shareholder abuse, such as the unfairly prejudicial conduct petition examined along with other minority shareholder protection mechanisms in Chapter 14. Principally found in the Companies Act 2006, laws designed to bring about effective corporate governance can also be found in insolvency law.

For the above reasons, a legalistic approach to the concept of corporate governance has been taken and this approach has been justified to date in relation to small, if not all, private companies. Broader-based corporate governance debates have focused on companies with publicly traded shares but this is changing. Corporate governance of unlisted companies is of increasing interest and can be seen in initiatives such as the Corporate Governance Guidance and Principles for Unlisted Companies in Europe published by the European Confederation of Directors’ Association. This development is evidenced by the 2011 EU Green Paper on The EU Corporate Governance Framework:

QUOTATION

‘Good corporate governance may also matter to shareholders in unlisted companies. While certain corporate governance issues are already addressed by company law provision on private companies, many areas are not covered. Corporate governance guidelines for unlisted і companies may need to be encouraged: proper and efficient governance is valuable also for unlisted companies, especially taking into account the economic importance of certain very large unlisted companies. Moreover, putting excessive burdens on listed companies could make listing less attractive. However, principles designed for listed companies cannot be simply transposed to unlisted companies, as the challenges they face are different. Some voluntary codes have already been drafted and initiatives taken by professional bodies at European or national level. So the question is whether any EU action is needed on corporate governance in unlisted companies.’

European Commission Green Paper, ‘The EU Corporate Governance Framework’ (COM(2011) 164 final) at p. 4

Corporate governance and large companies

In relation to large companies, corporate governance is typically addressed as a much more complex and broad-ranging concept because of the clear impact the quality of corporate governance of large companies with extensive business operations has on the economy and society. It is the role of law in corporate governance, however, that is, and must be, the focus of law courses. Even if we set aside questions of the role the law could and should play in improving corporate governance, the study of how existing company law influences corporate governance is more complex in relation to large companies than it is in relation to small companies. This complexity arises in part out of the model of ownership of many large companies.

The scope of impact of business operations

The larger the business of a company, the greater will be the impact of its operations, on individuals, other businesses, the community, the environment and, consequently, the economy and public interest. Consider the potential for the environment to be very significantly adversely affected by a company that owns and is actively expanding its network of oil pipelines. Similarly, a large company may run nuclear power stations producing by-products, best practice waste-management of which involves the storage into the long-term future of active nuclear material. A large company may employ a significant proportion of workers in a local community. It may be the largest purchaser of a particular product or products so that producers are dependent upon it continuing to buy a large share of their output (the four leading UK grocery chain corporate groups, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Morrisons and Asda exemplify this in relation to the purchase of food products). A large company (or corporate group) may be one of only a handful of suppliers of a particular consumer product or service with, consequently, millions of consumer (distinct from business) customers. Mobile telephone network service providers such as Telefonica (providing O2), EE (providing EE, Orange and T-Mobile), Vodafone and the currently much smaller but growing Hutchison Whampoa (providing 3, which was the first 3G network in the UK), illustrate this. Other suppliers of mobile phone services to consumers, such as Virgin Media, lease the right to use networks maintained by these four companies.

The point to note is that the effect of decision-making by such companies is not confined to the shareholders of the company or even to those (typically other companies or businesses) who have chosen to do business with the company. Decision-making by large companies can significantly affect the environment, the local community, the livelihood of large numbers of people who work for the company, consumer choice and the viability of suppliers. The various groups affected by, or interested in, a company are sometimes referred to as ‘stakeholders’.

The extent to which the interests of different stakeholders

as a matter of law, must be

as a matter of law, must be

as a matter of fact, are

as a matter of fact, are

as a matter of policy, should be

as a matter of policy, should be

taken into account in company decision-making are important questions that fall within the corporate governance rubric. Closely related questions are who must be, who is and who should be involved in company decision-making.

The extent to which each question is explored in a company law course will depend in large part upon the interests of the lecturers and tutors delivering the course. On a course in which the traditional approach, sometimes referred to as a ‘black letter law’ approach, is adopted, the focus will be on current rules and regulations to answer the first question and its corollary: as a matter of law to what extent must the interests of different stakeholders be taken into account and who must be involved in company decision-making. Even where this approach is adopted, however, introduction into core company law, in s 172 of the Companies Act 2006, of the concept of ‘enlightened shareholder value’ (a concept examined in Chapter 11 at 11.3.2) means that some analysis of the larger issues of corporate governance are called for, if only to explain this development and provide some insight into how s 172 may be interpreted in the future by boards of directors and the courts.

On a course in which a ‘law in context’ approach or a ‘socio-legal studies’ approach is adopted, time is likely to be spent focused on the third question and its corollary: as a matter of policy, to what extent should the interests of different stakeholders be taken into account in company decision-making and who should be involved in company decision-making. A wide range of approaches can be taken to this line of enquiry. An historical approach, for example, may involve reviewing initiatives in the UK over the years to engage workers in company decision-making. A comparative law approach may involve reviewing, comparing and contrasting company decision-making in a selection of legal jurisdictions across the world. A European Union perspective may be adopted, perhaps examining the dichotomy within the European Union between Member States with worker participation (such as Germany) and those without (such as the UK), a matter that has presented insuperable difficulties in harmonising company law in the European Union.

Writings of theorists in an array of scholarly disciplines, sociology and economics to name but two, may be drawn upon to explore corporate governance (as well as other aspects of company law) and underpin policy proposals. In particular, theories and models developed by economists have been drawn upon (extensively in the USA, in the EU and to a lesser, albeit influential, extent in the UK) to explore the operation of law, predict the effects of changes to company law and, more contentiously, propose what the law should be. This law and economics scholarship is more developed in relation to corporate governance issues raised by the phenomenon of the separation of ownership from the control/management of companies, an ownership structure that is addressed in the next section.

The second of the three questions identified above: to what extent are the interests of different stakeholders taken into account as a matter of practice and who actually takes part in (or perhaps the question should be, who actually influences) company decision-making, are questions of fact. The focus here needs to be on empirical studies yet, as it appears that little empirical research has taken place in the UK on decision-making in companies, this question is often answered, somewhat unsatisfactorily, by making assumptions.

Corporate governance and the separation of ownership and control of companies

The second factor adding to the complexity of corporate governance of large companies is the model of ownership of large publicly traded companies. Separation of those who ‘own’ a company (the shareholders) from those who run the company (the directors and executives) has long been a feature of large companies in the UK. This separation raises the problem of ensuring that those who manage and govern companies do not run them for their own personal benefit rather than for the benefit of those on whose behalf the law requires companies to be managed.

The management self-interest problem is exacerbated where a company’s shares are owned by a large number of shareholders with no single person owning a significant shareholding. This pattern of shareholding is called the ‘dispersed ownership structure’. It reflects modern portfolio theory which underpins investment risk management by diversification. The interest of almost all beneficial owners of shares in dispersed owner publicly traded companies is, first and foremost if not exclusively, financial in nature. Shareholders seek dividends, increased share value (that is, they want the price at which they can sell their shares to increase) and, ideally, both. This share ownership structure is said to reflect investor capitalism as distinct from entrepreneurial capitalism: shareholders are not interested in engaging in management and management hold an insignificant, if any, shareholding in the companies they manage.

In this type of company, legal protection based on a balance of power between the board of directors and shareholders has little if any meaningful effect exactly because shareholders have little inclination to exercise the powers reserved to the shareholding body: the divorce of ownership and control is virtually complete. Yet this scenario is believed to present the greatest risk of management and directors acting in their own self-interest rather than promoting the success of the company, and it is in relation to dispersed ownership companies that the most stringent laws promoting good practice in corporate governance are considered to be necessary. This explains why corporate governance law is more developed for companies with shares listed on stock exchanges than it is for private companies and unlisted public companies. It also explains why relevant laws are found not in core company law, but in securities law. Corporate governance law, beyond the Companies Act 2006, is made up of a combination of hard law (legislation such as the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and regulations and rules made pursuant to that Act) and ‘soft law’ such as guidance and, particularly, codes.

Two important codes designed to promote good corporate governance can be found on the Financial Reporting Council website (which is referenced at the end of this chapter). The UK Corporate Governance Code (the successor to the Combined Code) sets out good practice for boards of directors of companies with shares with a Premium Listing on the Main Market of the London Stock Exchange on issues such as board composition and effectiveness, risk management, director remuneration and relations with shareholders. The Code is subject to consultation and revision every two years. A company with a Premium Listing is required by the Listing Rules in the FCA Handbook to state in its annual report and accounts how it has applied the Main Principles set out in the UK Corporate Governance Code and whether it has complied or not with all relevant provisions of the code. It must set out any provisions with which it has not complied and give reasons for its non-compliance.

The newer UK Stewardship Code is aimed at enhancing the quality of engagement between asset managers and the companies in which they invest. It sets out good practice on engagement with companies, to which asset managers should aspire, to help improve efficient exercise of governance responsibilities. Currently, as is the case with the UK Corporate Governance Code, no legal obligation to comply with this code exists. However, unlike the UK Corporate Governance Code, no legally enforceable reporting obligations exist in relation to the UK Stewardship Code, not even ‘comply or explain’ reporting. Corporate governance codes from all around the world can be accessed on the European Corporate Governance Institute website referenced at the end of this chapter.

Corporate governance and large private and unquoted companies

Large private companies and large public companies with no publicly traded shares present a challenge to corporate governance law. They highlight what seems to be a structural difficulty with the current law, namely that enhancements to corporate governance laws, the justification for some of which arises from the implications of large-scale operations rather than the divorce of ownership from control, have been implemented by laws applicable only to publicly traded companies.

An example of this was the requirement in the Companies Act 2006 that companies report to the public information about the impact of their operations and decisions on the physical and social environment, company employees and the community, as well as disclosing company policies on these matters and the effectiveness of those policies. This obligation applied only if the company was a ‘quoted company’ as that term is defined in the Companies Act 2006. No private company or unquoted public company, regardless of how extensive its operations were, was subject to these reporting obligations. The legal obligation to publish a business review covering the matters outlined above has now been replaced by the obligation imposed on all companies except small companies to publish a strategic report (s 414C). The required contents of this report are considered under narrative reporting in Chapter 17.

Overlooked in the reform resulting in the Companies Act 2006, the problem of how to regulate the governance of large companies that are not publicly traded is an important challenge facing company law. In addition to being raised in the EU Corporate Governance Framework Green Paper quoted from above, the Reflection Group on the Future of EU Company Law, appointed by the European Commission, addressed this issue in its report published in April 2011.

QUOTATION

‘As it is important to avoid broad and imprecise categorisations, the Reflection Group is particularly concerned about the distinction between public and private limited companies that has traditionally dominated legislation within company law for more than a century. The origin of the distinction is the still correct observation that a company with a large and dispersed і crowd of shareholders may in certain respects warrant different regulation from a company with a small and closely knit circle of shareholders. However, in its traditional form the distinction relies on an inapt choice of company form, whereby a company is deemed “public” or “private” simply by its choice of company form. Thus, a “public company” does not necessarily have a large and dispersed crowd of shareholders; in fact, it may not even be listed and may have a single shareholder. Nor does a “private company” have to be a small company in any way; it can have more shareholders, more employees and a greater turnover than a “public company”.’

European Commission, ‘Report of the Reflection Group on the Future of EU Company Law’, Brussels (5 April 2011)

The approach to corporate governance taken in this book

Developments in share ownership patterns (including the more limited role and importance of traditional institutional investors, growth in the proportion of shares on publicly traded companies in overseas ownership and the creeping number of publicly traded companies with block-holding shareholders), concern and steps to regulate the gender composition of boards of directors, enhanced focus on shareholder engagement as a tool to improve corporate governance, the emergence of corporate governance guidance and codes for unlisted companies, heightened concern and steps to ensure effective governance of SMEs (driven by political focus on SMEs as important drivers of economic growth and employment), promotion of employee share ownership and sustained demand for corporate social and environmental responsibility to be given legal backing (the beginnings of which can arguably be seen in company law in narrative reporting developments) combine to make the study of corporate governance a fascinating and contentious field of study. Unfortunately, in a basic text on core company law, it is only possible to alert readers to the rich tapestry of interests and initiatives that make up the multi-faceted world of corporate governance. Before engaging with this complex realm, it is helpful to understand the relevance of core company law to corporate governance.

Large parts of the Companies Act 2006 can be characterised as laws existing to support and promote good practice in corporate governance. Being so pervasive, these laws are not separated out and expressly dealt with under the rubric ‘corporate governance’ (although that term is used as the title to Chapter 9 in which the key organs of governance, their composition and decision-making processes are examined). To the extent that securities regulation can be regarded as containing corporate governance provisions, limited space requires that a line be drawn somewhere and the only securities regulation covered briefly in this book is the framework of periodic and insider information reporting for publicly traded companies outlined in Chapter 17, the Prospectus Rules outlined in Chapter 7 and, because some of its provisions are so widely discussed and lend a fuller picture to some aspects of core company law, certain provisions of the UK Corporate Governance Code are examined at appropriate points in the text.

The impact of the quality of corporate governance on the political economy makes it an important topic of scholarly interest. Beyond examining the existing law, this book simply introduces readers to the enormous potential scope of this area of study and provides those interested in expanding their understanding with suggestions for further reading. An excellent starting point for those seeking to understand the European Union’s current approach to corporate governance is the European Commission EU Corporate Governance Framework Green Paper already referred to.

Statute law takes the lead in the sources of company law. The main statute containing company law is currently the Companies Act 2006. The most important statutes containing provisions regarded as part of core company law are:

Companies Act 2006;

Companies Act 2006;

Insolvency Act 1986;

Insolvency Act 1986;

Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986;

Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986;

Financial Services and Markets Act 2000;

Financial Services and Markets Act 2000;

Criminal Justice Act 1993 (insider dealing);

Criminal Justice Act 1993 (insider dealing);

Companies Act 1985 (company investigations);

Companies Act 1985 (company investigations);

Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act 2004 (company investigations and community interest companies (CICs)).

Companies (Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise) Act 2004 (company investigations and community interest companies (CICs)).

BIS

The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (formerly BERR and before that the DTI) is the government department responsible for company law (amongst other things)