International Aviation Law

15

International Aviation Law

No flying machine will ever fly from New York to Paris.

Orville Wright

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should:

1. understand how annexes are added to the Chicago Convention;

2. understand how the ICAO is organized and the scope of its authority;

3. know the five freedoms of the air;

4. understand the distinction between a restricted bilateral agreement and an open skies agreement;

5. understand what rights are afforded to a defendant who is being prosecuted pursuant to the Tokyo Convention;

6. be familiar with the distinction between the Warsaw Convention and the Montreal Convention;

7. understand the role of the DOT and the European Aviation Safety Agency in applying international aviation agreements.

INTERNATIONAL AIRSPACE

International law generally accepts that a country’s sovereign airspace includes the airspace above a country as well as the airspace above a country’s territorial waters. Territorial waters extend 12 nautical miles out from a nation’s coastline. Airspace not within any country’s territorial limit is considered international. A country may, by international agreement, assume responsibility for controlling parts of international airspace, such as those over the oceans or the poles. For example, the US provides air traffic control services over a large part of the Pacific and smaller parts of the Atlantic Ocean, even though the airspace is international in nature. Canada, Iceland, and the UK share the responsibility for the rest of the northern Atlantic airspace. Canada and Russia share responsibility for northern polar airspace.

There is no international agreement concerning the vertical boundaries of a country’s airspace. It is generally recognized that no country controls space, but there is no international agreement concerning where airspace ends and space begins. As countries move toward increased space flight and as the possibility for civilian space flight becomes more realistic, this is an area that will require attention.

THE CHICAGO CONVENTION

Prior to the Second World War, international flight was regulated by a patchwork of hundreds of individual agreements between countries. This system was cumbersome and inefficient, but aviation technology had not yet progressed to a point where air travel could fully compete with other established modes of international travel, such as rail and ship. In the run-up to the war, little emphasis was placed on international flight agreements because so much attention was being devoted to de-escalating the growing conflict.

The war had the unintended consequence of obliterating old geographic and political barriers to international flight. With only three dominant world powers remaining, it became uniquely possible to develop a new framework for international aviation agreements. The war also spurred significant advances in aviation technology that could be adapted for civilian use. During the war, aircraft became faster, stronger, and more fuel-efficient – all qualities that are of significant benefit to civilian air commerce. Because of wartime manufacturing needs, the necessary factories and skilled workers were already in place to become the foundation for a thriving civil aviation manufacturing sector.

The Second World War created not only the means for international air travel but also the will. The magnitude of the war left world governments with a firm desire to usher in a new era of cooperation and peace. To that end, delegates from 52 countries signed the Convention on International Civil Aviation shortly before the official end of hostilities in Europe. The agreement is generally referred to as the Chicago Convention because it was signed in Chicago, Illinois. The Convention established a framework that eventually resulted in a common system of international aviation rules. It included provisions for safety and environmental regulations, and also defined the rights and obligations of every nation as they relate to international airline operations.

The Convention was designed to replace the hundreds of patchwork individual agreements with a common system that would permit international commercial aviation to flourish. It only applies to international commercial air travel; it does not apply to military operations, domestic commercial air travel, or private aircraft operations. The purpose behind this unified approach to civil aviation can best be described by the introduction to the Convention:

Whereas the future development of international civil aviation can greatly help to create and preserve friendship and understanding among the nations and peoples of the world, yet its abuse can become a threat to the general security; and

Whereas it is desirable to avoid friction and to promote that co-operation between nations and peoples upon which the peace of the world depends;

Therefore, the undersigned governments having agreed on certain principles and arrangements in order that international civil aviation may be developed in a safe and orderly manner and that international air transport services may be established on the basis of equality of opportunity and operated soundly and economically; have accordingly concluded this convention to that end.

THE ICAO

For international air travel to be efficient and effective, there must be a uniform system of air regulations. A patchwork approach is an impediment to the free flow of air traffic across international borders. In order to foster the development of a uniform approach to air regulations, the Chicago Convention created an international governing body – the ICAO. Its purpose is to “develop the principles and techniques of international air navigation and to foster the planning and development of international air transport.”

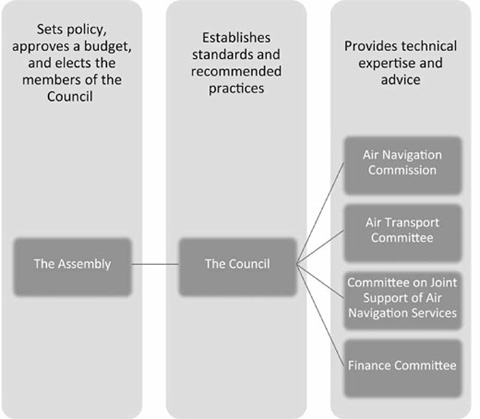

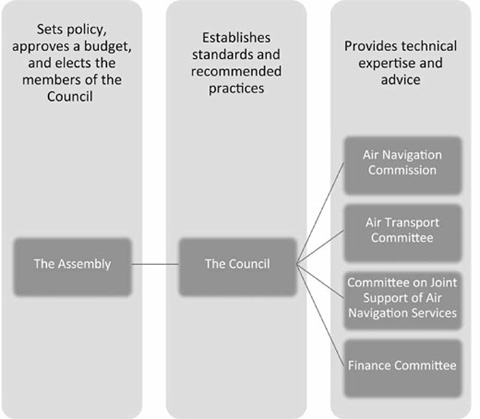

The ICAO is body of the UN and it is responsible for developing uniform air transportation standards that apply to international flight. The ICAO is divided into three branches. The Assembly is a representative body that meets every three years to review the ICAO’s work, set policy, approve a budget, and select which Member States will have a seat on the rule-making body of the ICAO, known as the Council. The Assembly is also responsible for approving any amendments to the Chicago Convention, which are then subject to ratification by each of the Member States.

The Secretariat is the executive department of the ICAO and is responsible for implementing the policies set by the Assembly. It is headed by a Secretary General and is divided into five divisions, each with its own area of expertise: the Air Navigation Bureau, the Air Transport Bureau, the Technical Co-Operation Bureau, the Legal Bureau, and the Bureau of Administration and Services. The various bureaus are responsible for implementing safety plans and environmental protection policies, and for monitoring the effectiveness of the ICAO’s Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs).

The Council is the rule-making body of the ICAO and is responsible for debating and adopting SARPs for air travel. The Council receives advice and technical expertise from various commissions and committees.

Figure 15.1 Organizational structure of the ICAO

The ICAO’s Rule-Making Authority

SARPs concern specifications for physical characteristics, materials, configuration, performance, personnel, or procedure. If approved by two-thirds of the Council, SARPs are incorporated into the Chicago Convention as Annexes. Standards are considered necessary for the safety or regularity of international air navigation. Recommended Practices, while not strictly necessary, are strongly encouraged. Article 37 of the Chicago Convention explains the scope of the ICAO’s rule-making authority.

Article 37 – Adoption of international standards and procedures

Each contracting State undertakes to collaborate in securing the highest practicable degree of uniformity in regulations, standards, procedures, and organization in relation to aircraft, personnel, airways and auxiliary services in all matters in which such uniformity will facilitate and improve air navigation.

(a) Communications systems and air navigation aids, including ground marking;

(b) Characteristics of airports and landing areas;

(c) Rules of the air and air traffic control practices;

(d) Licensing of operating and mechanical personnel;

(e) Airworthiness of aircraft;

(f) Registration and identification of aircraft;

(g) Collection and exchange of meteorological information;

(h) Log books;

(i) Aeronautical maps and charts;

(j) Customs and immigration procedures;

(k) Aircraft in distress and investigation of accidents; and such other matters concerned with the safety, regularity, and efficiency of air navigation as may from time to time appear appropriate.

To date, the ICAO has adopted 18 Annexes to the Chicago Convention dealing with issues such as the training and licensing of aviation personnel, airworthiness, ATC, accident investigation, and environmental protection. A list of the current annexes is provided below:

1. Annex 1 – Personnel Licensing

2. Annex 2 – Rules of the Air

3. Annex 3 – Meteorological Services

4. Annex 4 – Aeronautical Charts

5. Annex 5 – Units of Measurement

6. Annex 6 – Operation of Aircraft

7. Annex 7 – Aircraft Nationality and Registration Marks

8. Annex 8 – Airworthiness of Aircraft

9. Annex 9 – Facilitation

10. Annex 10 – Aeronautical Telecommunications

11. Annex 11 – Air Traffic Services

12. Annex 12 – Search and Rescue

13. Annex 13 – Aircraft Accident and Incident Investigation

14. Annex 14 – Aerodromes

15. Annex 15 – Aeronautical Information Services

16. Annex 16 – Environmental Protection

18. Annex 18 – The Safe Transportation of Dangerous Goods by Air

Annexes are not laws and the ICAO does not have legal authority to enforce them. Instead, they are guidelines that Member States may use to promulgate their own aviation regulations. Under the Chicago Convention, Member States that deviate from the ICAO’s Standards are required to notify the ICAO of their intention not to fully comply with an Annex. Member States are also encouraged, but are not obligated, to notify the ICAO if they do not intend to comply with a Recommended Practice. Article 38 explains:

Article 38 – Departures from international standards and procedures

Any State which finds it impracticable to comply in all respects with any such international standard or procedure, or to bring its own regulations or practices into full accord with any international standard or procedure after amendment of the latter, or which deems it necessary to adopt regulations or practices differing in any particular respect from those established by an international standard, shall give immediate notification to the International Civil Aviation Organization of the differences between its own practice and that established by the international standard. In the case of amendments to international standards, any State which does not make the appropriate amendments to its own regulations or practices shall give notice to the Council within sixty days of the adoption of the amendment to the international standard, or indicate the action which it proposes to take.

In any such case, the Council shall make immediate notification to all other states of the difference which exists between one or more features of an international standard and the corresponding national practice of that State.

Freedoms of the Air

At the Chicago Convention, the US urged the delegates to adopt a set of aviation rights known as freedoms of the air. Other countries, wary that the dominant US aviation industry would monopolize world air travel if such broad aviation rights were enacted, declined to incorporate these rights into the Convention on International Civil Aviation. Instead, the freedoms of the air were placed in two separate agreements called the International Air Services Transit Agreement and the International Air Transport Agreement. These agreements are open to any country that signs the Convention on International Civil Aviation. The five freedoms of the air are discussed below.

First Freedom of the Air

The first freedom is the right granted by one country to another to fly across its territory without landing. For example, an airline of country A may overfly country B enroute to country C. The first freedom is sometimes called either the transit freedom or the technical freedom. First freedom rights are almost always granted with prior notification of the flight usually required.

Second Freedom of the Air

The second freedom is the right granted to land in a country for technical reasons, such as refueling or maintenance, but not for commercial reasons. For example, an airline from country A might land in country B to refuel or perform maintenance while on its way to country C, but it is not allowed to load or unload passengers. Second-freedom rights are not utilized as much as they used to be. Prior to the advent of long-range jetliners, airports such as Anchorage, Alaska, Shannon (Ireland), and Reykjavik were commonly used as refueling airports. Second freedom rights are usually routinely granted with prior notification required.

Third Freedom of the Air

The third freedom is the right granted by one country to another to land for the purpose of disembarking passengers who boarded in the originating country. For example, an airline of country A is permitted to enplane passengers in country A, fly to country B, and disembark the passengers there. The nationality of each passenger is of no concern with this or any other freedom. Nationality concerns are covered by separate immigration and security rules. Freedom three simply defines the right of the airline to fly between two countries.

Fourth Freedom of the Air

The fourth freedom is the right granted by one country to another to land for the purpose of enplaning passengers to return to the airlines country of origin. For example, an airline of country A is permitted to enplane passengers in country B and return them back to country A. Just like freedom three, the nationality of each passenger does not matter; this freedom is concerned with the nationality of the airline itself. Third and fourth freedom rights are normally granted concurrently in the air service agreement agreed to by two countries.

Fifth Freedom of the Air

The fifth freedom is the right granted by one country to another to land in a second country, pick up new passengers in the second country, and take them to a third country. For example, an airline of country A might fly to country B, pick up passengers in country B, and fly them to country C. An extension of the fifth freedom rights would permit the airline of country A to bring passengers back from country C to country B. Fifth freedom rights are rarely granted as they essentially give a foreign airline a right to serve two unrelated countries, albeit those connected by a previous flight.

The sixth and seventh freedoms of the air are generally accepted, but are not specifically included in either the International Air Services Transit Agreement or the International Air Transport Agreement. The sixth freedom of the air is the right to carry passengers from one country to another, with a stop in the airline’s home country. Under this freedom, an airline of country A could pick up passengers in country B, stop in country A, and then fly to country C. The seventh freedom of the air is similar to the sixth, except that there is no stop in country A; in other words, an airline of country A could pick up passengers in country B and disembark them in country C.

The eighth and ninth freedoms of the air are also not included in the International Air Services Transit Agreement or the International Air Transport Agreement. These freedoms protect the right of cabotage and are less commonly accepted than the sixth and seventh freedoms. Cabotage is the carriage of goods or passengers within a single country by an airline of a foreign country. It is common within Europe, but its acceptance outside the EU is more limited. The eighth freedom of the air guarantees the right of country A to stop at a two locations in country B before returning to country A. The ninth freedom of the air guarantees with right of an airline to conduct domestic operations within a foreign country, without connecting to the country of origin. For example, Ryanair is an airline based in Ireland that has routes connecting Rome and Milan in Italy without stops in Ireland.