Interest Groups and Their Influence on Judicial Policy

Interest Groups and Their Influence on Judicial Policy1

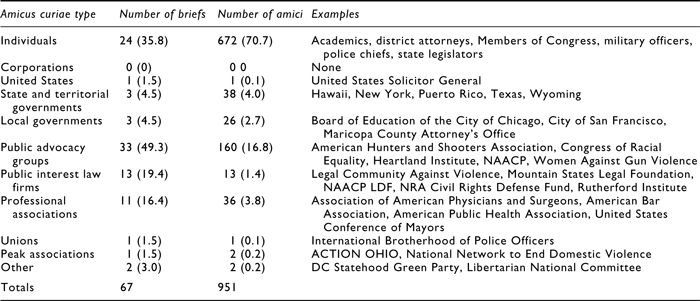

Interest groups participate in virtually all aspects of the American political and legal systems. In electoral politics, organizations regularly make campaign donations to candidates and many groups endorse individuals seeking political office. In the legislative sphere, interest groups draft legislation, testify in front of committees, and meet with legislators in hopes of having their preferred policies written into law. In the executive branch, organizations monitor the implementation of policies, testify before regulatory boards, and work with bureaucrats in an attempt to ensure that their prerogatives are reflected in policy implementation. More generally, interest groups mount grassroots lobbying campaigns, aimed at building public support for the groups’ goals, in addition to engaging in orchestrated efforts to educate the public regarding their agendas and policy objectives. And, of course, groups are no strangers to the American judiciary. In recent years, interest groups have participated in more than 90% of cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court (Collins 2008, 47).

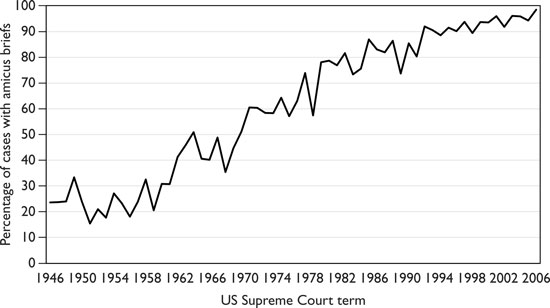

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the role of interest groups in the United States Supreme Court, paying special attention to the primary means of interest group involvement in the judiciary: amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) participation. This method of lobbying is a staple of interest group activity in the American legal system, as well as other legal systems throughout the world. First, the various methods of interest group litigation in the American courts are addressed. Next, I provide a treatment of interest group amicus curiae participation in the Supreme Court. It is illustrated that, in recent years, virtually all Supreme Court cases are accompanied by amicus curiae briefs and these briefs are filed across a wide spectrum of issue areas. Following this, I discuss the types of organizations that file amicus briefs in the Supreme Court. I provide evidence that a diverse array of interest groups actively participate, indicating that a host of organizations find a voice in the Court. Fourth, I provide an overview of extant scholarship on amicus influence on the Supreme Court. This chapter closes with a brief conclusion section suggesting directions for future research on amicus curiae participation in the Supreme Court, as well as interest group litigation in other judicial venues.

Interest Group Litigation in the American Legal System

In the U.S. courts, interest groups have four primary means of participation. First, interest groups can initiate test cases. Using this strategy, interest groups can either challenge a law or policy in their own name (provided they can secure standing), or, alternatively, orchestrate litigation on behalf of an individual (or individuals) who can demonstrate standing to sue.2 An example of the former occurred in Ysursa v. Pocatello Education Association (2009), in which a coalition of labor unions unsuccessfully sued State of Idaho officials challenging a state law that prohibited payroll deductions for “political activities” on the grounds that it violated the First Amendment’s freedom of speech clause. Perhaps the most famous example of the latter occurred in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). In that case, the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) Legal Defense and Education Fund recruited litigants in Topeka, Kansas, and other cities, to challenge the practice of racial segregation in public schools. This litigation campaign resulted in the Supreme Court’s landmark desegregation decision, in which the Court declared that the “separate but equal” doctrine was unconstitutional in the field of public education.

A second method of interest group participation in the American legal system involves case sponsorship. Like test cases, under this strategy, an organization provides attorneys, staff, and other resources for a party in exchange for using the litigation to pursue its policy goals. This means of participation differs from test cases in that case sponsorship occurs after the initial litigation has already commenced. In this sense, groups look for “targets of opportunity” by taking over cases that individuals have begun once the litigation reaches the appellate courts. For example, Moore v. Dempsey (1923) began when 12 black sharecroppers were convicted of first-degree murder in Arkansas for allegedly killing five whites during a riot. At their trials, a veritable mob of heavily armed whites stood outside of the courtroom, demanding guilty verdicts and the death sentence for each defendant. Moreover, the crowd made it clear that, should the judge fail to return death sentences for the defendants, the mob would lynch them. The accused met their attorneys for the first time when the trail began, their lawyers failed to produce witnesses on their clients’ behalves, and the defendants did not testify in their defense. The jury returned guilty verdicts for all of the defendants in less than 10 minutes and the judge subsequently sentenced the defendants to death. Upon becoming informed of the case, the NAACP sent a representative from the organization, Walter White, to investigate. Concluding that the trials were a sham, White convinced the NAACP to sponsor an appeal. The case ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which determined that the defendants’ rights to due process of law were violated (Cortner 1988).

A third method of interest group involvement in the American legal system involves intervention, in which an organization becomes what is effectively a party to the litigation after the case has entered the legal system. Under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24(a), organizations, and other interested entities, have the opportunity to intervene in a case as a matter of right, while Rule 24(b) authorizes intervention, not as a matter of right, but when the prospective intervenor “has a claim or defense that shares with the main action a common question of law or fact.” Rule 24(a) specifies that an organization seeking intervenor status must demonstrate either that it is authorized to intervene under federal statute or that it has “an interest relating to the property or transaction that is the subject of the action,” such that the disposition of the litigation would impair the prospective intervenor’s interests. Moreover, the would-be intervenor must illustrate that its interests would not be adequately represented by the direct parties to litigation. Should an organization successfully obtain intervenor status, the intervenor becomes, in effect, a full-blown participant in litigation, bound by the resulting judgment in the case, not only as a matter of precedent, but as a matter of res judicata (Hilliker 1981).3 Attesting to the reality that intervenors in American law are effectively litigants, they are authorized to make motions, introduce new legal arguments, and, at the trial court level, present evidence and witnesses.

While Rule 24(a) seems to indicate that there are few procedural barriers to becoming an intervenor as a matter of right, in practice, the federal courts treat all requests to intervene as discretionary decisions (Hilliker 1981; Tobias 1991). That is, the U.S. Supreme Court has failed to articulate a bright line rule (that is, a rule subject to minimal interpretation) as to exactly what an applicant must show to intervene under Rule 24(a). This responsibility has been left to lower federal courts, which have applied myriad standards with regard to allowing intervention as a matter of right (Tobias 1991, 415). Because of the various standards utilized to determine whether an organization is authorized to intervene, and because many courts deny motions to intervene, concluding that the prospective intervenor was not able to demonstrate a clear interest in the litigation, a practical impairment, or inadequate representation by the parties, this method of interest group litigation is used rather sparingly. Instead, organizations most commonly advance their interests through the amicus curiae brief (Goepp 2002; Hilliker 1981, 23).

Amicus curiae briefs act as the primary method of interest group involvement in the U.S. courts (Collins 2008).4 While the literal translation of amicus curiae, “friend of the court,” implies neutrality, these briefs are, in fact, used as adversarial weapons, providing a means for organizations to pursue their interests in the adversarial system that is American law (Krislov 1963). Indeed, there was never a time in American jurisprudence that amici acted solely as neutral third parties (Banner 2003). As amici curiae, organizations pursue their policy goals by providing courts with information not addressed by the direct parties to litigation, presenting alternative or reframed legal arguments, and addressing the far-ranging policy implications of a court’s decisions. In addition, because many amici are specialists in particular areas of economic, legal, or social policy, they frequently supply courts with social scientific information to further their policy agendas (Rustad and Koenig 1993).

The U.S. Supreme Court maintains an open-door policy with regard to the participation of organized interests (Collins 2008, 42; Kearney and Merrill 2000, 761). Under Supreme Court Rule 37, private amici must obtain written permission from the parties to litigation to file an amicus curiae brief.5 However, representatives of state, local, and territorial governments, as well as the federal government, need not fulfill this procedural requirement. Practically speaking, the requirement of party consent is negligible, as virtually all litigants willingly comply with requests by amici. Should one (or both) of the litigants fail to provide consent to file, the prospective amicus may petition the Court for leave to file. This motion must be accompanied by the amicus brief. The Court’s treatment of these motions—to almost always grant motions for consent to file, provided they are timely—further evidences its open-door policy. For example, during the 1994 term, the Court granted 99.1% of motions for leave to file amicus briefs, denying only a single motion (Epstein and Knight 1999, 225).

Under U.S. Supreme Court Rule 37, amici are directed to indicate the position taken in the brief (i.e., affirmance or reversal of the lower court) and are instructed to provide a statement of interest, outlining how the case affects their well-being. Rule 37 further specifies that the Court does not favor the input of third parties that merely repeat the arguments raised by the litigants:

An amicus curiae brief that brings to the attention of the Court relevant matter not already brought to its attention by the parties may be of considerable help to the Court. An amicus curiae brief that does not serve this purpose burdens the Court, and its filing is not favored.

In what can appropriately be viewed as an effort to enhance the ability of amici to reduce the repetition of arguments raised by the litigants, in 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court amended its rule governing the due dates for amicus briefs filed in its decisions on the merits. Prior to this rule change, amicus briefs were due on the same date as the brief of the party the amici supported. This rule change extended this by a week, requiring that amici submit their briefs no later than seven days after the brief of the party they support is filed with the Court.6

A 1997 amendment to Rule 37 requires that amici divulge whether the attorneys for the parties to litigation authored the amicus briefs, in whole or in part, and additionally compels amici to indicate whether any entities, other than those listed as amici curiae, made monetary contributions to fund the preparation of the amicus brief. Although the U.S. Supreme Court provided no justification for this rule change, Kearney and Merrill (2000, 767) suggest that a possible explanation for the former points to the Court’s concern that attorneys for the litigants were “ghostwriting” amicus briefs, enabling them to evade the Court’s page limits for litigant briefs and present additional argumentation to support their positions. As to the latter, it is plausible that the justices’ may have feared amicus briefs were being manipulated as a means of showing apparently broad support for a cause of interest.7

Amicus Curiae Participation in the U.S. Supreme Court

Organized interests have long used the U.S. Supreme Court to pursue their policy goals. The first amicus brief filed by a non-governmental interest group occurred in 1904 when the Chinese Charitable and Benevolent Association of New York acted as an amicus in Ah How (alias Louie Ah How) v. United States (1904), a case involving the deportation of Chinese immigrants in New York (Krislov 1963, 707). In the following decades, a wide range of organizations filed amicus briefs in the Court, including the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Farm Bureau Association, the League for Economic Equality, the NAACP, the National Consumers League, and the National Association of Cotton Manufacturers (Collins 2008, 41). By the post-World War II era, amicus participation was a regular occurrence in the Court.

Figure 12.1 plots the percentage of U.S. Supreme Court cases, decided with oral argument, in which at least one amicus curiae brief was filed during the Court’s 1946–2007 terms.8 As this figure makes clear, there has been a marked rise in the percentage of cases with amicus participation over the course of the last 60 years. From 1946–1960, the percentage of cases with amicus briefs was relatively stable, averaging 23%. A rather dramatic surge occurred during the 1960s, when the percentage of cases with amicus participation increased from 31% in 1961 to 44% in 1969. This swell in amicus participation is no doubt due in part to the striking increase in the number of interest groups operating in American politics during this period (Berry 1997). Following the explosion of amicus participation in the 1960s, later decades witnessed more stable increases. For example, the percentage of cases with amicus briefs in the 1970s was 60% and the 1980s saw this number increase to 80%. By the mid-1990s, the percentage of cases with amicus briefs effectively stabilized at over 90%, reaching a high of 98% in 2007. As such, these data make clear that it is a rare occurrence in the contemporary U.S. Supreme Court that a case is not accompanied by the participation of amici curiae.

Figure 12.1 Percentage of U.S. Supreme Court cases with amicus curiae participation, 1946–2007 terms.

While Figure 12.1 provides useful information regarding the overall percentage of cases in which amicus briefs are filed, it cannot speak to whether certain issue areas exhibit more or less amicus activity. Figure 12.2