Implied Trusts

Chapter 3

Implied Trusts

Chapter Contents

The Background to Implied Trusts

Having introduced implied trusts in Chapter 2, it is important that you understand the nature and workings of such trusts before your study of the overall law of trusts can continue in more detail. Implied trusts are gap-fillers and will arise when there is no valid express trust to regulate the relationship between the settlor, trustee and beneficiary.

As You Read

In this chapter, the types and characteristics of implied trusts are addressed. Accordingly, as you read, you should look out for the following issues:

what implied trusts are;

what implied trusts are;

the resulting trust: the occasions on which this type of trust can arise, how it operates and what its effect is; and

the resulting trust: the occasions on which this type of trust can arise, how it operates and what its effect is; and

the constructive trust: again, when it arises, its effects and the issue of whether it can be taken forward outside its traditional remit into some sort of general remedial device.

the constructive trust: again, when it arises, its effects and the issue of whether it can be taken forward outside its traditional remit into some sort of general remedial device.

The Background to Implied Trusts

The requirement of form

It is probably fair to say that usually trusts created under English law are done so deliberately. As was shown in Chapter 2,1 most trusts are formed involving three parties:

(a) the settlor, who creates the trust;

(b) the trustee, who holds the legal interest in the trust property and who administers the trust; and

(c) the beneficiary, who holds the equitable interest in the trust property, who enjoys the trust but who also acts as an ‘enforcer’ of the trust, ensuring that the trustee honours the terms of the trust.1

Most trusts that are formed deliberately — or expressly — do not have to comply with any requirements as to form. That means that they can, for the most part, be created entirely orally. For example, a settlor can simply instruct a trustee to hold property for a beneficiary’s benefit. The hallmark of such express trusts is that they are created by the settlor’s intention.

A major exception to this principle exists, however, for trusts which have land as their subject matter. All trusts which are expressly created and have land as all, or part, of their subject matter are caught by a statutory provision which means that they must be evidenced in writing. There is no option for settlors to circumvent this requirement,3 for the wording of s 53(l)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 is prescriptive. It provides:

a declaration of trust respecting any land or any interest therein must be manifested and proved by some writing signed by some person who is able to declare such trust or by his will….

For most legal rules there are exceptions and the provision in s 53(1)(b) follows that tradition. The exception is contained in the next sub-section, which provides that ‘[t]his section does not affect the creation or operation of resulting, implied or constructive trusts’.4

Section 53(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925 consequently permits all implied trusts to be created entirely orally, even where their subject matter is land. Implied trusts can, therefore, be created by the parties quite informally and flexibly. As we shall see in this chapter, though, that is not necessarily the case and the courts have restricted the growth of what appears to be, at first glance, a highly malleable form of trust.

Implied Trusts — A Definition

If express trusts are created by the deliberate intention of the settlor, implied trusts are generally not. Instead, they arise by operation of law: through equity deciding that a trust should apply to a particular situation. There are two main types of implied trust: the resulting trust and the constructive trust.

The resulting trust

The name ‘resulting’ is derived from the Latin word resalire which means ‘to jump back’. This means that if a resulting trust exists, the equitable interest jumps back to the settlor instead of remaining permanently with a different beneficiary. The consequence is the settlor wears two hats — one as settlor and the second as beneficiary.

Resulting trusts are said to arise in one of two circumstances. These two circumstances were set out by Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC.5

He explained that a resulting trust would arise in the first case (‘Category A’):

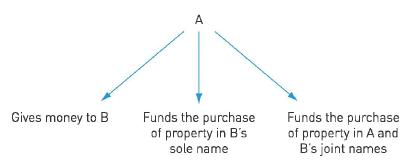

where A makes a voluntary payment to B or pays (wholly or in part) for the purchase of property which is vested either in B alone or in the joint names of A and B …6

There are, in fact, three separate situations occurring in Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s first example. For clarity, they are set out in Figure 3.1.

This means that equity will presume that A did not really intend to make some sort of gift to B, but instead really wanted to keep hold of the property for himself. Equity takes a cynical view of each of these transactions. Equity cannot quite believe that, in these situations, A would deliberately wish to give their money away to B. Equity acts in a paternalistic, protective manner for A’s benefit.

Before we get too carried away and assume that equity will never allow one person to give something to another, as Lord Browne-Wilkinson stressed in the case, it is only a presumption that equity makes in such transactions. This presumption can be overturned — or rebutted — by, for example, evidence that A really did wish to transfer property to B. In Vandervell v IRC,7 Lord Upjohn emphasised that the presumption of a resulting trust in these cases was ‘no more than a long stop to provide the answer when the relevant facts and circumstances fail to yield a solution’.8

The second situation (‘Category B’) in which Lord Browne-Wilkinson said that a resulting trust would arise was ‘[w]here A transfers property to B on express trusts, but the trusts declared do not exhaust the whole beneficial interest …’9

This essentially arises where A has made a mistake in creating an express trust. Instead of establishing a trust of the entire equitable interest in the property, A has created a trust of part only of the equitable interest. Since equity abhors a vacuum, the remaining part of the property cannot exist in limbo. The device of the resulting trust is used to fill in that gap and the entire equitable interest will be held on resulting trust for the settlor.10

Divergence of views of the basis of a resulting trust

Aside from Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s belief that a resulting trust arises from the parties’ intentions, there have been other views expressed as to the basis of such trusts. Megarry J in Re Vandervell’s Trusts (No. 2)11 thought that the first type of resulting trust arose by what were presumed to be the intentions of the settlor. Such resulting trusts could be categorised as ‘presumed resulting trusts’.12 The second type, in his view, arose automatically by operation of law. His view was that any express trust which accidentally failed to dispose of the entire equitable interest in property would not contain evidence of the settlor’s intentions as to what should occur to the remaining non-disposed part of the equitable interest. He labelled the second type of resulting trusts as ‘automatic resulting trusts’.13

This theoretical distinction as to the basis for both types of resulting trust was rejected by Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Westdeutsche Laadesbaai Girozentrale v Islington LBC.14 Lord Browne-Wilkinson believed that both types of resulting trust operated by ‘giving effect to the common intention of the parties’.15 That means that, as his Lordship stated, ‘[a] resulting trust is not imposed by law against the intentions of the trustee …but gives effect to his presumed intention’.16

It could not be said, thought Lord Browne-Wilkinson, that if a settlor had abandoned an equitable interest that a resulting trust would step in automatically in his favour and return the equitable interest to him. If the court could not ascertain the settlor’s intentions in such a situation, then the logical inference had to be that such property would pass on a bona vacantia basis to the Crown.17 The basis for resulting trusts had to be the settlor’s presumed intention.

Glossary: Bona vacantia

The Treasury Solicitor’s website reminds us that bona vacantia means ‘empty goods’. It arises where no-one owns the goods and so they pass to the Crown, as a type of ‘default’ position. More modern terminology might refer to the goods as ‘ownerless’. The Treasury Solicitor administers the goods on behalf of the Crown. Have a look at www.bonavacantia.gov.uk for a modern insight as to what this part of the Treasury Solicitor’s Department undertakes.

The approaches of Megarry J and Lord Browne-Wilkinson were arguably linked together by Lord Millett in Air Jamaica Ltd v Charlton18 where he said, ‘[l]ike a constructive trust, a resulting trust arises by operation of law, though unlike a constructive trust it gives effect to intention’.19

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

Do you prefer the views of Lord Browne-Wilkinson or Megarry J for the basis of a resulting trust? The difficulty with Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s notion that the resulting trust is founded on a settlor’s intention is exemplified in his Category B type of resulting trust. How can it be said that in the case of a failed express trust, the settlor still intended to have the equitable interest returned to him? Surely his intention of a settlor is merely to create an express trust and a settlor usually gives no thought to the consequences of his express trust failing.

In the discussion which follows, for the sake of consistency, Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s classification of the types of resulting trust is followed.

Category A resulting trusts: From a voluntary transfer

In this category, it is the intentions of the donor (A) which are paramount: if A truly intended to benefit B, then the gift will stand in B’s favour. If A’s intentions cannot be proven, equity will step in with a resulting trust in A’s favour.20 When equity steps in with a resulting trust, the fundamental idea at work is that A did not intend to benefit B in any way, despite first appearances from the transaction which has taken place. B receives the property as a volunteer since he provided no consideration for the property he received. Equity will not assist a volunteer. This type of resulting trust was found to occur on the facts of Re Vinogradoff.21

The case concerned a transfer of War Loan shares by a grandmother into hers and her granddaughter’s joint names. By her will, the grandmother purported to leave her interest in the shares to a third party. The executors of the grandmother’s will brought an action to ascertain whether the granddaughter had any interest in the shares or whether they were rightly left by the terms of the will. That, of course, depended on whether the grandmother had truly intended to make a gift of the shares into hers and her granddaughter’s joint names. If such clear intention could not be shown, equity would step in with a resulting trust in favour of the grandmother’s estate.

The court held that the intention was to create a resulting trust in favour of the grandmother which would now clearly benefit her estate. The shares would, therefore, go to the third party under the will, not to the granddaughter.

This presumption of a resulting trust can easily be rebutted if evidence can be led which shows that A did, in fact, intend to benefit B.

Alternatively, it used to be the case that the presumption of a resulting trust could be rebutted by a different presumption: the presumption of advancement. As will be shown, the presumption of advancement will be abolished22 so the only way to rebut the presumption of a resulting trust being imposed in the future will be to show evidence that a true gift was intended. It is necessary, however, to consider what the presumption of advancement is and how it operates to defeat the presumption of a resulting trust. Whilst it is due to be abolished, the presumption of advancement is explicitly preserved for anything done, or obligations incurred, before s 199 of the Equality Act 2010 comes into effect.23

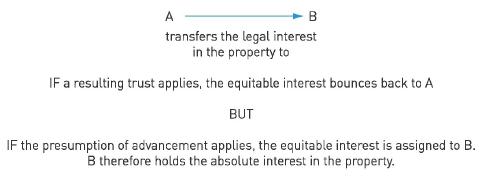

The presumption of advancement

The presumption of advancement provided that, where A and B enjoyed a certain type of relationship, any gift of property by A for B would be recognised by equity as being a true gift in B’s favour. A resulting trust would not, therefore, be implied. B’s equitable interest in the property would be recognised and secure. This can be shown in Figure 3.2.

The presumption of advancement applied to gifts between husband and wife and father and child.24 Note that the presumption was like going down a one-way street in that it only applied to gifts going in a particular direction. It applied only for gifts given by husbands to wives and by fathers to children. It did not apply for gifts given by wives to husbands or children to fathers.

The presumption of advancement applied to a gift between a fiancé and fiancée where they were later married: Moate v Moate.25 In 1930, a man and woman agreed to purchase a home together. The purchase of the property was completed whilst the parties were engaged, but some three weeks before they married. At the man’s request, the legal ownership of the property was put into the woman’s name. The actual purchase price of the property was paid by the man, subject to a mortgage. Whilst the wife was contractually bound to pay the mortgage, the man always paid the instalments as they fell due and eventually paid off the mortgage in its entirety.

Some 16 years after the property was purchased, the parties’ relationship broke down. The issue for the court to resolve was who enjoyed the equitable ownership of the property. The man’s argument rested on the basis that he had effectively paid for the property in its entirety and so a resulting trust should be found in his favour.

Jenkins J held that the presumption of advancement applied in favour of the woman. The husband had originally intended the house to be a gift to his wife providing the marriage actually took place which, of course, had occurred. The mortgage repayments also benefited from the presumption of advancement working as the man had failed to discharge the presumption that they were not made as gifts to his wife.

The case effectively extended the presumption of advancement from applying between husbands and wives to those intending to be married. Jenkins J had no difficulty with this. He believed the presumption of advancement would be stronger between fiancees in any event. It would be entirely natural for a man to give a woman a gift of a property as a wedding present before the wedding took place.

The presumption of advancement rested upon what might now be seen to be oldfashioned beliefs that certain people would naturally wish to provide for others. It was natural for a husband to wish to take care of and provide for his wife. Pragmatically, it was necessary for husbands to do so, since the majority of married women could not own property in their own right before 1882.26 Similarly, it was natural for a father to wish to take care of and provide for his child. But the presumption of advancement was fairly narrowly constrained. For example, it was originally not the case that the presumption of advancement would apply as of right to gifts between mothers and their children, as Bennet v Bennet27 illustrated.28

The case concerned a loan of £3,000 from Ann Bennet to her son, Philip which was made in 1869. In 1875, Philip predeceased his mother with the amount of the loan still owing to her. She claimed that she was a creditor of his estate. The defendant, another creditor, argued that she had no claim, since the presumption of advancement applied between a mother and child which meant that the money had been given to Philip. Nothing was repayable to the mother, since it was a gift by virtue of this presumption. Jessel MR held that no gift had been intended. There was no moral duty for a mother to provide for her child. As such, the presumption of advancement could not apply. Philip’s estate had to repay the loan.

By the late twentieth century, the presumption of advancement had become very weak, as explained by Lord Hodson in Pettitt v Pettitt:

Reference has been made to the ‘presumption of advancement’ in favour of a wife in receipt of a benefit from her husband. In the old days when a wife’s right to property was limited, the presumption, no doubt, had great importance and today, when there are no living witnesses to a transaction and inferences have to be drawn, there may be no other guide to a decision as to property rights than by resort to the presumption of advancement. I do not think it would often happen that when evidence had been given, the presumption would today have any decisive effect.29

Indeed, the presumption itself had always been able to be rebutted by evidence to the contrary, as occurred on the facts in the well-known case of Marshal v Crutwell.30

Henry Marshal’s health was failing. He went to the London and County Bank, withdrew all of his money from his own personal account and placed it in a new joint account in his own name and that of his wife. He told his bank to honour any cheques drawn on the new account by either of them.

In fact, after these events occurred, Henry never drew a cheque on the account, but his wife did so, using the money for household purposes. After Henry’s death, his wife argued that all of the money left in the account belonged to her. She argued that the presumption of advancement applied: that it could be presumed that Henry had intended to benefit her with the money.

Sir George Jessel MR held that the presumption of advancement was rebutted on the facts. Taking into account all of the facts and especially Henry’s ill health, he said that the opening of the joint account was a ‘mere arrangement of convenience’31 as opposed to a case where Henry was giving the money to his wife. The arrangement that Henry set up enabled his wife to draw cheques on the account whilst he was alive; this was different from giving her the money for her use absolutely after his death.

The presumption of advancement, therefore, had lost much of its impetus over the years. The Equality Act 2010 was enacted, amongst other reasons, to reduce ‘socio-economic inequalities’ and to ‘amend the law relating to rights and responsibilities in family relationships’.32 The presumption of advancement offends principles of equality by benefiting women to the exclusion of men. Consequently, the whole principle of the presumption of advancement, having generally been reduced in importance by successive case law since its heyday in the nineteenth century, has been abolished in its entirety in s 199(1). By way of exception, s 199(2) permits the presumption to survive for anything done before section 199 commences or anything done pursuant to an obligation incurred before the section commences.

Category B resulting trusts: Created where the entire equitable interest is not exhausted

This was the second category of resulting trusts recognised by Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington LBC.33

This second category of resulting trust can itself be created in one of two situations:

[a] where, upon creation of the trust, the settlor made an error by failing to transfer all of their equitable interest to the trustee; or

[a] where, although the trust was created properly, it was created with a condition attached to it and that condition has come to an end.

We need to consider each of these two instances in turn.

Category B: Where the settlor makes an error

Key Learning Point

It is essential that you understand the next cases of Vandervell v IRC and Re Vandervell’s Trusts (No. 2) if you are to fully grasp this type of resulting trust. These cases are perhaps the most famous litigation in the entire law of trusts.

This type of resulting trust was found to have occurred on the facts in Vandervell v IRC.34

The case itself concerned some of the taxation affairs of Mr Guy Vandervell. He was the controlling shareholder in Vandervell Products Ltd, an engineering company. The company had various categories of shares, amongst which were 100,000 ‘A’ ordinary shares. As a wealthy man, Mr Vandervell had some concerns about his estate being liable for a large amount of tax when he died. He could afford to divest himself of some of his property so that his estate would not be subject to so much tax upon his death.

The Royal College of Surgeons, coincidentally and at the same time as Mr Vandervell was worried about his taxation, was seeking donations. In response to this, Mr Vandervell decided to give the Royal College the sum of £150,000 to establish a Chair of Pharmacology.

Mr Vandervell was not simply going to write a cheque for this amount to the Royal College, however. Instead, his financial advisor suggested giving the Royal College all of the ‘A’ shares in Vandervell Products Ltd. The company could then declare a dividend on these shares to the sum of £150,000. The Royal College would still get its funds. At the same time, by giving the shares away to the Royal College, Mr Vandervell would have divested himself of some of his property for tax purposes.

The plan thus far seemed solid enough. The problems for Mr Vandervell began when his financial advisor recommended that he include an option to buy back the shares in the arrangement with the Royal College, in case Vandervell Products Ltd was ever converted into a public limited company. The financial advisor thought that it would be awkward to potential outside investors for the Royal College to have such a significant shareholding in the company. An option would clearly give Mr Vandervell the right to buy back the shares before any public flotation of the company occurred.

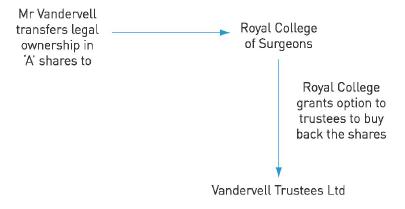

An option was, therefore, granted in favour of another of Mr Vandervell’s companies, Vandervell Trustees Ltd. This was a company whose object was really just to manage trusts.

The arrangement was put into effect. The Royal College became the legal owner of the ‘A’ shares in Vandervell Products Ltd. As promised by Mr Vandervell, dividends were declared on the shares, to the net amount of £157,000, for the benefit of the Royal College.

The Royal College was a charitable trust. As such, it decided to reclaim the tax that had already been paid on the dividends declared to it. That meant that the Inland Revenue started to look into the arrangement that had been made between Mr Vandervell, Vandervell Trustees Ltd and the Royal College. The Inland Revenue claimed that the effect of the option agreement to buy back the shares meant that Mr Vandervell had never really relinquished control of those shares. He still owned the equitable interest in them. If he had never relinquished control of them, they were still owned by him and he was liable to pay a large amount of additional ‘surtax’ on them which amounted to £250,000.

Part of the argument of the Inland Revenue was that a resulting trust existed with Mr Vandervell as beneficiary. Their argument is set out diagrammatically in Figure 3.3 below.

The case went to the House of Lords. On this issue, the House of Lords agreed with the Inland Revenue. The Royal College did indeed hold the shares on resulting trust.

What is particularly interesting about the case is that Vandervell Trustees Ltd had no firm idea of who would benefit from the shares if they decided to buy them back from the Royal College by exercising the option. This did not cause any difficulty for the House of Lords to find a resulting trust. Lord Wilberforce said:

The conclusion, on the facts found, is simply that the option was vested in the trustee company as a trustee on trusts, not defined at the time, possibly to be defined later.35

Lord Wilberforce then acknowledged the potential difficulty with that concept which was that the equitable interest could, if the trusts were not defined, simply remain in the air. For reasons of certainty,36 it is generally not possible to have a trust with no equitable interest vesting in a beneficiary. His response to that difficulty was, ‘the equitable, or beneficial, interest cannot remain in the air: the consequence in law must be that it remains in the settlor’.37

This conclusion for Lord Wilberforce was a pragmatic operation of this category of resulting trust:

There is no need to consider some of the more refined intellectualities of the doctrine of resulting trust, nor to speculate whether, in possible circumstances, the shares might be applicable for Mr Vandervell’s benefit: he had, as the direct result of the option and of the failure to place the beneficial interest in it securely away from him, not divested himself absolutely of the shares which it controlled.38

The difficulty with Lord Wilberforce’s opinion, however, is that he held that the equitable interest remained with Mr Vandervell at all times. This seems not to fit instinctively with the orthodox principle of a resulting trust that the equitable interest jumps back to the settlor.

From 1961 until early 1965, dividends of over £769,000 net of tax were declared on the shares. In early 1965, Mr Vandervell formally executed a Deed of Release. This document released any interest that Mr Vandervell may still have had in the shares to Vandervell Trustees Ltd. The issue now became as to the operative effect of that document and precisely when it released Mr Vandervell from liability to taxation. Was it in 1961, so that its effect was retrospec-tive, or only from 1965, when it was executed?

This became the issue in what was actually the third part of the Vandervell litigation — Re Vandervell’s Trusts (No. 2).39 The Inland Revenue was of the view that, despite the letter indicating that the shares were to be held for the children’s trust, it was only by the formal Deed of Release that Mr Vandervell’s equitable interest was transferred to that trust.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Somewhat sadly, Mr Vandervell did not live to see the outcome of the case. He died in 1967 and judgment was only given by the Court of Appeal in 1974.

The Court of Appeal held that the resulting trust that had been found by the House of Lords in the earlier case40 had come to an end when Vandervell Trustees Ltd had exercised the option in 1961 to buy back the shares. At that time, legal ownership in the shares was transferred to the trustee company. Due to this, the trustee company could (and did) then declare a trust in favour of the children. Lord Denning MR highlighted41 three important points of evidence which supported this conclusion:

[a] the money to buy back the shares came from the children’s trust which would have been a breach of that trust, unless something (i.e. the shares) were to be put into that trust;

[b]the existence of the letter from the trustee company to the Inland Revenue, in which it was explained that the shares would, from the date of the exercise of the option, be held for the children’s trust; and

[c] all dividends on the shares after the option had been exercised were paid by the trustee company to the children’s trust.

Lord Denning MR explained how the resulting trust came to an end in the case:42

A resulting trust for the settlor is born and dies without any writing at all. It comes into existence whenever there is a gap in the beneficial ownership. It ceases to exist whenever that gap is filled by someone becoming beneficially entitled.