Human Rights, Health and Development

Human Rights, Health and Development

Introduction

Those who work on the implementation of human rights, improved health for all and human development have in common aspirations to improve human welfare, the relationships between people, and the environments in which we live. Each reflects shared individual and collective aspirations for a better life, and is grounded in both moral and instrumental values revolving around fundamental concepts of dignity, justice, wellbeing and progress. While all three areas have long histories of struggle, the events of the last two centuries have underlined their global significance, the need for deepening our understanding of their links and the importance of developing analytical tools to identify and manage the potential offered by a human rights approach to improving health and the process of development.

These events include the 19th century industrial revolution in Europe and the resulting expectations of an improved quality of life contrasting dramatically with the health and social inequalities increasingly visible in the streets and factories of mushrooming cities (Frank and Mustard 1994). Public health and medical advances followed, seeking through human ingenuity to apply science to address emerging problems. States that had built their industries competed with one another for economic and political influence and several states extensively exploited poorer ones through colonial domination. The atrocities of World War II led to recognition of a compelling need to set out the obligations of governments towards their populations as well as towards each other (Lauren 1998). The process of decolonisation in the 1960s, the end of the cold war in the 1990s (Tarantola 2008), and the subsequent emergence of new independent States as the process of economic globalisation rapidly escalated (Benedek et al. 2008) drew more political and public attention to global inequalities in health, disparities in wealth and the need for the realisation of human rights. The unabated spread of HIV since the early 1980s and the global response to the epidemic launched in 1987 advanced the understanding of the interdependence of health and human rights. In particular, it highlighted the fact that those subjected to discrimination and violations of other human rights—especially those living in poverty—were disproportionately affected by HIV (Mann & Tarantola 1996).

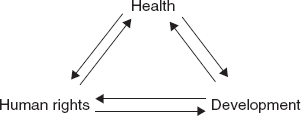

This paper explores the links between human rights concerns, improving the health of individuals and communities, and the goals and processes of development that are central to improving people’s living standards and life chances. It builds its analysis around a simple conceptual framework (Figure 10.1) which illustrates the interdependence of health, development and human rights. It highlights the underlying principles, values and prominent features of human rights, health and development as independent domains, and then describes their interactions. It focuses particular attention on how these linkages can be analysed and reinforced in practice. This chapter also proposes that a Health, Human Rights and Development Impact Assessment (HHRDIA) may be a practical approach that builds on the synergies between the three domains, providing structured and transparent monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to enhance accountability for progress, while revealing shortcomings in policy processes, and improve human welfare outcomes.

Figure 10.1 Health, human rights and development

Human Rights, Health and Development: Aspirations, Values and Disciplines

The strong causal links between human rights, health policies and programs and progressive development approaches can be demonstrated through a variety of perspectives. These include: starting with human rights (their origins and constitution being explored below); their human value (aimed at improving people’s lives); social relevance (consideration of the individual as part of social constructs); normative content (standards and directions for national governance and international cooperation); instrumental application (frameworks of analysis; policy formulation, program development and evaluation); disciplinary base (exploration, documentation, research and teaching of theory and practice in separate academic institutions); and the ways in which they engage communities (building on community awareness-raising, participation and leadership). Although it risks over-simplification, for clarity of exposition we refer to health, human rights, and development below as three “domains.” This section summarises the key features of each domain, in order to set out the common, cross-disciplinary information-base necessary for identifying and building upon their inter-relationships—the main objective of this contribution.

Human Rights

In the modern world human rights are often invoked to justify a variety of fundamental political, social, economic and cultural claims. The origins of rights (whether anchored in natural law, positive law, a theory of human needs, capabilities and flourishing, or some other theoretical position) and their justifications are diverse. There is nevertheless considerable international consensus about a central core of human rights claims, in particular those embodied in explicit international obligations accepted by Nation-States in the principal United Nations (UN) and regional human rights instruments adopted since World War II (see, for example, Centre for the Study of Human Rights 2005). This is so notwithstanding the challenges of cultural relativism and the need for universal human rights to be realised in the specific contexts of different communities (Baxi 2002; Steiner & Alston 2000). Challenges to dominant discourses of human rights have come in waves, with new claims to the enjoyment of universally guaranteed rights being brought by marginalised groups (racial and ethnic minorities, women, children, persons with disabilities, among others), who realise both the promise of rights and the shortfall in their practical enjoyment. Enriched by new perspectives, human rights today play an important role in shaping public policies, programs and practice aimed at improving actual and potential individual and social welfare.

Human Rights as State Obligations

Human rights constitute a set of normative principles and standards which can be traced back to antiquity although they received their particular modern imprint through the work of political philosophers and leaders of some 17th century European countries (Tomuschat 2003), and those who developed and expanded upon their ideas. The atrocities perpetrated during World War II gave rise, in 1948, to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and later to a series of treaties and conventions which codified the aspirational nature of the UDHR into instruments which would be binding on States through international human rights law. Among these are the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), both of which entered into force in 1976. Similar developments have also been seen at the regional level, frequently with more effective institutions for the monitoring and enforcement of those norms.

Human rights are often described as claims that individuals have on governments (and sometimes on others, including private actors such as corporations), simply by virtue of being human. In the case of the international human rights treaties and under many domestic legal systems these entitlements are embodied in legal instruments which are formally binding on States and their institutions. The formal guarantee of a right does not of itself mean that the rights-holder enjoys the right in practice and, despite their formal entitlements, people are often constrained in their ability to realise those rights fully, or indeed at all. Those most vulnerable to violations or neglect of their rights are often those with the least power to contest the denial of their rights. As a result, their well-being and health may be adversely affected (Farmer 2004).

The relationship between the individual or group who is the rights-holder and the State is central to the concept and practical enjoyment of human rights, and it is the nature and scope of the State’s obligations (including in relation to the actions of private actors) which are central to the understanding of how human rights may be promoted and protected in practice (see box below).

Nature of Human Rights and a Typology of States’ Obligations

Fundamental human rights are posited as inalienable (individuals cannot lose these rights any more than they can cease being human beings); as indivisible (individuals cannot be denied a right because it is deemed a less important right or something non-essential); and as interdependent (all human rights are part of a complementary framework, the enjoyment of one right affecting and being affected by all others) (Vienna Declaration 1993).

Currently, the most influential approach at the international level to understanding the different dimensions of human rights is a tripartite typology of the nature and extent of States’ obligations: in relation to all rights, governments have obligations to respect, protect and fulfil each right (Maastricht 1997). Firstly, States must respect human rights, which requires governments to refrain from interfering directly or indirectly with the enjoyment of human rights. Secondly, States also have the obligation to protect human rights, which requires governments to take measures that prevent non-State actors from interfering with the enjoyment of human rights, and to provide legal and other appropriate forms of redress which are accessible and effective for such infringements. Finally, States have the obligation to fulfil human rights, which requires States to adopt appropriate legislative, administrative, budgetary, judicial, promotional and other measures towards the full realisation of human rights, thus creating the conditions in which persons are able to enjoy their rights fully in practice. This typology has proved particularly useful in elaborating the specific content of many economic and social rights—including the right to health.

It has been common to distinguish between civil and political rights (sometimes called “negative rights” or liberties), and economic, social and cultural rights (sometimes referred to as “positive rights”). This approach has been debunked as inaccurate and outdated (Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action 1993, art2). All rights may involve the allocation of resources (for example, the classical civil right to a fair trial is premised on the existence of a legal system resourced with judges, court buildings and legal aid). Even those rights traditionally thought of as subject only to progressive realisation have elements which require immediate action to be taken (for example, in relation to ensuring that all enjoy the right to education, carrying out a baseline analysis, the development of a plan which should be “deliberate, concrete and targeted as clearly as possible towards meeting the obligations”) (UN CESCR General Comment 3), and may have justiciable elements (Eide 1995).

The Right to Health

The right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health—or the right to health as it is commonly referred to—appears in one form or another in many international and regional human rights documents. Furthermore, nearly every other article in these international instruments also has clear implications for health. The right to health builds on, but is not limited to, Article 12 of the ICESCR. Most of the other principal international and regional human rights treaties contain provisions relevant to health, for example, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

The right to health does not mean the right to be healthy as such, but embodies an obligation on the part of the government to create the conditions necessary for individuals to achieve their optimal health status. In 2000 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights adopted a General Comment explicating the substance of government obligations relating to the right to health (UN CESCR General Comment No 14). In addition to clarifying governmental responsibility for policies, programs and practices influencing the conditions necessary for health, it sets out requirements for the delivery of health services, including their availability, acceptability, accessibility and quality. It lays out directions for the practical application of Article 12 and proposes a monitoring framework indicating the ways in which the State’s responsibility can be implemented through national law. Currently, over 100 national Constitutions have recognised a right to health and this number continues to increase as Constitutions are rewritten or updated (Kinney 2001).

The interrelatedness of human rights, development as a process and improved health status as a measure of development can be seen clearly in the context of the right to health. Rights relating to autonomy, information, education, food and nutrition, freedom of association, reproduction, equality, sexuality, participation and nondiscrimination are integral and indivisible elements of the achievement of the highest attainable standard of health. So too is the enjoyment of the right to health, inseparable from the enjoyment of most other rights, whether they are categorised as civil and political, economic, social or cultural (for example, the enjoyment of the right to work, the right to education, or the right to family life) (Leary 1994). The discourse of gender, reproductive and sexual rights also highlights the interdependency of human rights. A woman’s right to health cuts across the economic, social and cultural as well as civil and political rights, affecting the individual, as well as the entire family unit (Petchesky 2003). This recognition is based on empirical observation and on a growing body of evidence which establishes the impact that lack of fulfilment of these rights has on people’s health status—education, non-discrimination, food and nutrition epitomise this relationship (Gruskin & Tarantola 2001). Conversely, ill-health may constrain the fulfilment of all rights, as the capacity of individuals to claim and enjoy all their human rights may depend on their physical, mental and social well-being. For example, when States fail to fulfil their obligations, ill-health may result in discrimination—as is commonly seen in the context of HIV, cancer or mental illness. It may cause arbitrary termination or denial of employment, housing or social security, and limit access to food or to education with the consequence that social and economic development potentials may not be achieved.

The tripartite typology of human rights obligations—to respect, to protect, and to fulfill—originally developed in the context of economic and social rights (Eide 1995) has been particularly useful in indicating what steps a government should take in relation to each dimension of its obligations. In the context of the right to health, the obligation to respect means that no health policy, practice, program or legal measure should directly violate the individual’s right to health, for example, by exposing individuals to a known health hazard. Policies should ensure the provision of health services to all population groups on the basis of equality and freedom from discrimination, paying particular attention to vulnerable and marginalised groups (Hunt 2008). The obligation to protect, in relation to the right to health, means that governments must appropriately regulate such important non-State actors as the health care industry (including private health care and social services providers, pharmaceutical and health insurance companies) and, more generally, national and multinational enterprises whose contribution to market economies can also significantly affect the lifestyle, work life and health of both individuals and communities. The array of non-State actors is diverse and growing. It includes commercial enterprises whose activities have a major impact on the environment—such as energy-producing companies, manufacturers and agricultural producers—as well as the food industry and the media. Each of these actors has the capacity to promote and protect, or to neglect and violate, the right to health (and other rights) within their field of activity. Finally, the obligation to fulfil the right to health includes a duty to put into place appropriate health and health-related policies which ensure human rights promotion and protection with an immediate focus on vulnerable and marginalised groups where the value of health and other benefits to individuals and groups may be higher.

The Right to Development

In 1986 the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Right to Development, Article 1 of which states that “the right to development is an inalienable human right by virtue of which every human person and all peoples are entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized” (Declaration on the Right to Development). The human person is identified as the beneficiary of the right to development, as of all human rights. The right can be invoked both by individuals and by peoples and imposes obligations on individual States to ensure equal and adequate access to essential resources, and on the international community to promote fair development policies and effective international cooperation. The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action adopted by the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights recognised that democracy, development, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms are interdependent and mutually reinforcing (Vienna 1993, art 8). The Vienna Declaration reaffirmed the right to development as a universal and inalienable right and an integral part of fundamental human rights. It also made clear that, while development facilitates the enjoyment of all human rights, a lack of development may not be invoked to justify the abridgement of other internationally recognised human rights (Vienna 1993, art 10).

The declaration of the right to development has been controversial because some critics have seen it as having the potential for abuse by the State, which may use it to suppress concrete human rights ostensibly in order to ensure the realisation of the more amorphous right to development. Critics have also expressed concern that the State, rather than individuals or peoples, may in effect become the rights-holder, with low-income states being entitled to claim assistance from higher-income ones (see Kirchmeir 2006). Nevertheless, there is clearly a close relationship between the right to development and the right to health—enjoyment of the right to an adequate standard of health is both a goal of the exercise of the right to development, and a means of contributing to achieving development (Sengupta 2002; Marks 2005).

Health in Transition

Perspectives on health reflect the rapidly changing realities and opportunities in today’s globalised world. Responding to health needs is ultimately determined by how we address the issue of rights and access to power and resources. This section seeks to identify core achievements of public health, the methods and approaches which have underpinned such achievements, and the challenges of engaging with transforming policy-making and service delivery structures.

The World Health Organization defined health in 1948, in its constitution, as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO 1948, 1). The definition has been modified to also include the ability to lead a “socially and economically productive life.” Sen (1999) has identified health as a key determinant of the ability of an individual or group to benefit from a broader set of rights and entitlements. Public health, defined as “the art and science of preventing disease, promoting health, and prolonging life through the organised effort of society” (Acheson 1988), describes well the challenges facing the field. It also reinforces widespread recognition that promoting health requires multi-sector and “upstream” efforts to address the determinants of health, much more than simply improving access to health care (Baum 2007; Baum & Harris 2006).

Over the past two centuries, better education, improved nutrition and environmental advances, including better water and sanitation, safer working conditions and improved housing, have enhanced health outcomes (Frank & Mustard 1994; WHO 1999). Life expectancy has greatly increased in many medium and high income countries and major causes of mortality in early childhood, in particular, have been, or have the potential to be, addressed. Technologies have been developed to tackle infectious diseases, injuries and non-communicable diseases, as well as to treat and manage ill-health. Despite these significant achievements in dealing with exposures which pose a risk to life, including childbirth itself (Freedman et al. 2007), the benefits of economic advances, human security and access to health care, have not been shared equally, and significant disparities exist both within and between countries (WHO 1995). Preventable child mortality remains unacceptably high in many poor nations, in particular in Africa (Black et al. 2003). In some countries, notably those mired in conflict or under repressive regimes, population health has deteriorated (Zwi et al. 2002) and the poorest communities are often significantly worse off.

In the past half century, the ability to control many potentially lethal infectious diseases has been achieved through better understanding of their causes, development of technologies to interrupt exposure or prevent occurrence, improved diagnosis, treatment and management, and, in the case of smallpox, the ability to eradicate an organism. Prevention and control of non-communicable diseases has been much less successful. Smoking-related diseases, obesity, cancer and injuries, are all on the increase; mental health problems, too, at a population-wide level have not been effectively addressed (Boutayeb 2006). Many countries need to simultaneously confront both communicable and non-communicable diseases (Lopez et al. 2006).

While the new public health, as enunciated in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (Ottawa Charter 1986), highlighted efforts to build healthy public policy, create supportive environments, strengthen community action and reorient health services towards a health promoting perspective, the achievement in these areas has been limited (Leger 2007; Wise & Nutbeam 2007). The Charter’s definition of health as being “created by caring for oneself and others, by being able to take decisions and have control over one’s life circumstances, and by ensuring that the society one lives in creates conditions that allow the attainment of health by all its members” is a reality not experienced by many worldwide (Ottawa Charter 1986, art 3).

The role of the State in health services provision and in securing the basic needs required for health and development has been challenged and in many cases undermined. Increasingly, the private sector and other non-State actors have been brought into the process of providing care, often within an economic and ideological framework which positions health care as yet another commodity, without recognising the existence of significant market failures. Powerful non-State actors are increasingly involved in shaping the agenda around public health (Cohen 2006). Multilateral organisations, private foundations and the World Bank have in most cases become more influential than the World Health Organization in shaping public health policies and health care service responses in low and middle income countries (Martens 2003).

New supranational funds, such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, provide substantial funds but also may end up determining how countries address major health problems (Garrett 2007). Public-private partnerships have proliferated, securing public investment to produce new technologies and programs, but also shaping what services are available and under what circumstances (Buse & Walt 2000a and 2000b; Richter 2004). Private foundations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, make available more funds to health development activities than any other bilateral or multilateral agency, determining priorities and shifting health and research resources with limited or no system of accountability to those often most affected by such decisions (Okie 2006). A casualty of the changed mechanisms through which development funding is made available has been the strengthening of health systems and human resource capacity not only to deliver specified programs, but to provide a comprehensive framework within which improved health, equity of access, better outcomes and greater participation can be secured. Strengthening health services has become urgent, given the gap between investments and the actual benefits that have been observed (WHO 2007).

Determinants of Health

Key health issues and challenges are increasingly presented as technical issues, requiring the engagement of “experts.” This is contested by commentators and civil society organisations, such as the People’s Health Movement, which draw attention to the pivotal role of communities, nongovernmental organisations and the State in constructing the environment in which rights to health and broader development can be promoted and secured (People’s Health Movement 2006).

While health is increasingly understood as related to a wide range of determinants, and there is recognition that health is far more than health care, strategies to secure the commitment and resources required to overcome inequities in access to these determinants of health is lacking. The ability to shape and frame how inequalities and inequities are seen, the way in which they are defined and tackled, and from where the resources to address them should come, remains crucial. Rights, politics and power are arguably moving to centre stage (Farmer 2004).

Human Development

Human development is a qualitative as well as a quantitative improvement in the level (and standards) of individual and collective welfare—welfare that includes elements contributing to self-sustenance, self-esteem and freedom and is a general goal sought by individuals, groups, Nation-States and the international community. It is also specific and can be targeted at people whose level of welfare lags below those of others and is below their potential (Thirlwall 1999). For general improvement in measures of individual and collective welfare and development to occur, factors such as the status of human rights that play a role in determining the capacity of individuals and groups to realise it must be considered.

The means adopted to achieve improvements in individual and social welfare have evolved unevenly over time as human knowledge, economic capacity and institutional sophistication have grown. It is also clearly recognised that the status of any individual or group of people is dependent for its existence on the recognition and respect exercised by others and therefore to be successful, a process of development should incorporate a “rights” perspective (Frankovits et al. 2001).

Development and Change

The process of change and development, as noted by economists from Adam Smith onwards, has never been regular, linear or distributed evenly. Indeed, it became more uneven with the advent of capitalism as social, cultural and political innovation (with an accompanying decay of traditional social, economic and political systems), capital accumulation, market development, technological change and associated nation State building accelerated in northern Europe and spread outwards. The process of development can be seen as a qualitative change in conditions and an essential prerequisite to quantitative change measured as growth. Joseph Schumpeter described this as “creative destruction,” accelerating first in the most developed countries and spreading in irregular waves across the world (Schumpeter 1969, 253). Processes of change have seen the destruction and displacement of significant parts of pre-existing values (cultures) and patterns of social and economic relations, including embedded rights, in households, rural and urban settlements and nation States. New personal and social systems of rights (including property), relations, production systems and governance structures emerged to change the distribution of income and systems of social, economic and political authority (see North in Atkinson et al. 2005).

From Liberal to Neo-Liberal Model of Development