Human Rights-Based Approach to Tobacco Control

Human Rights-Based Approach to Tobacco Control

Human Rights-Based Approach to Tobacco Control

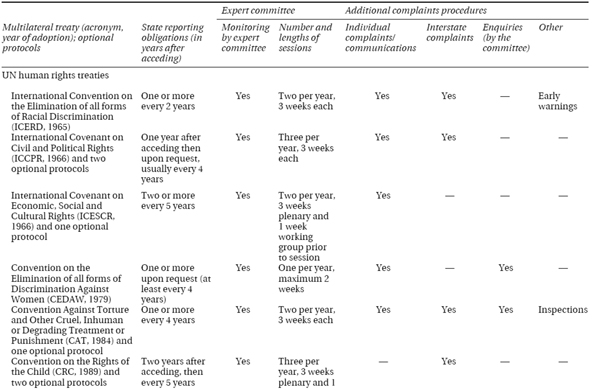

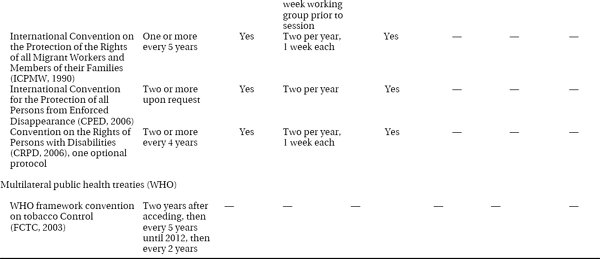

Human rights rhetoric became universally defined with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, specifically related to health with: ‘the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being of himself and his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social service’.1 Since then, nine core international human rights treaties have been adopted and brought into force (Table 32.1). Of particular relevance to the rights relative to health and well-being, under which tobacco control would be pertinent are: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 1966), the Convention on the Elimination on Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 1979) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 1989). To ensure that the agreed rights are also enjoyed in practice, each of these treaties has clear and independent mechanisms to monitor the implementation of the respective treaty provisions.

Table 32.1 Monitoring instruments and complaints procedures contained in the UN Human Rights Treaties vis à vis the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

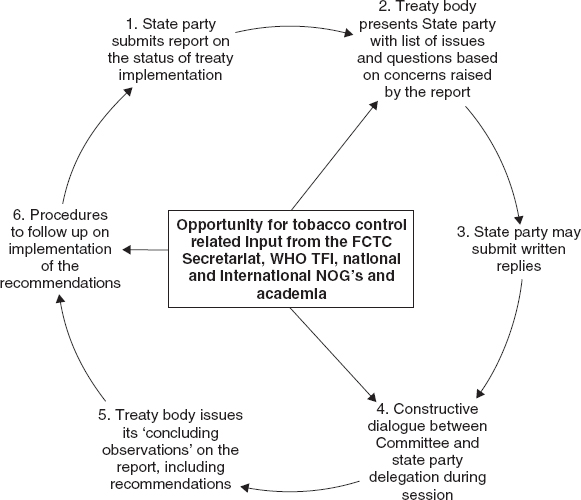

Unlike the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC),2 the core human rights treaties rely on periodic reporting by the state parties and additionally have international committees of independent experts (treaty bodies) to regularly monitor national implementation and report back to the UN system. These treaty bodies consist of 10 to 23 internationally recognized independent experts who are nominated and elected by state parties. The committees receive reports from state parties as well as additional information on the human rights situation in the respective country, examine them in a dialogue with government representatives and publish their concerns and recommendations as ‘concluding observations/comments’. Some treaty bodies introduced further monitoring mechanisms including an enquiry procedure, the examination of interstate complaints and the examination of individual complaints (Table 32.1). The treaties complement each other, are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. That said, many countries have derogated from important portions of treaties, have ignored implementation or adherence because of lack of will or ability to do so. Often the ability to adhere or progress on treaty implementation is hampered by financial constraints. If there are not financial resources to allow full implementation of a treaty requirement, then progressive realisation of the right is to be expected as finances allow.

A key principle underpinning human rights is the recognition of states’ obligations to respect, protect and fulfil these international rights. Most states in the world are party to most of the human rights conventions, the USA unfortunately being a notable exception. An excellent example is Uruguay, which is party to the nine core human rights treaties, but significantly the ICESCR, CEDAW, CRC and the FCTC, and works diligently to respect, protect and fulfil fundamental human rights—pertinently, as they apply to tobacco control.3 Uruguay has established comprehensive smoke-free laws, dedicated a portion of its tobacco tax to health related purposes, has required pictorial warnings on cigarettes packs, has banned electronic cigarettes and has established evidence-based tobacco cessation guidelines that include support for nicotine replacement and bupropion.

From the Right to Health to the Right to Tobacco Control?

By tightly adhering to the principles that have been delineated for interpreting human rights, one can construct legal claims to rights related to tobacco control.4 These would include human rights more broadly than just the right to health. All human rights are interrelated, interdependent and indivisible. States have a duty (see http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rights-human/for discussion of rights and duties) to provide all human rights to the best of their economic and political ability. In many poorly resourced countries this can be difficult as the tobacco industry, with its unlimited resources, can overwhelm states’ best intentions to comply with health-based rights by using those resources strategically in ways that undermine tobacco control progress. States and their citizens must be empowered with knowledge, resources and ability to claim their rights and resist the tobacco industry’s ‘corporate social responsibility’, ‘corporate social investment’ or outright bribery that can inhibit realisations of such rights. An example of tobacco industry corporate social responsibility is the establishment by the tobacco industry of Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing, while hundreds of thousands of children are still working in tobacco production (including bidi rolling).5 Educated and empowered citizens give the human rights-based approach to tobacco control its utility. The right to health, or the right to the highest attainable standard of health, is claimed within Article 12 of the ICESCR. This right is then further elucidated and defined within a structure that is called a General Comment (see Box 32.1). The key axioms that underpin a human rights-based approach to tobacco control are derived from Article 12 of the ICESCR, General Comment 14: