Formalities for the Sale of Land

Whether property is unregistered or registered, whether a huge amount is paid for it or whether it is a gift, in order for property to be legally transferred from one party to another, the transfer must be made by deed. We will be considering the requirements for a valid deed later on in the chapter.

Conveyancing practice goes beyond this simple requirement for a deed, however. The majority of property sales and purchases follow a standardised system of conveyancing practice that has evolved over a period time, the purpose of which is not only to ensure that the property is transferred legally, but also to take into account a number of practical considerations and precautions. There are two reasons for this:

1. Land is a valuable asset. When an individual buys their home, it is in all likelihood the most expensive purchase they will ever make. It is therefore essential to ensure the buyer is getting what they pay for before they commit themselves to making the purchase.

2. The sale and purchase of land in England and Wales is underpinned by the Latin maxim: caveat emptor, which means ‘let the buyer beware’.

Caveat emptor – ‘let the buyer beware’.

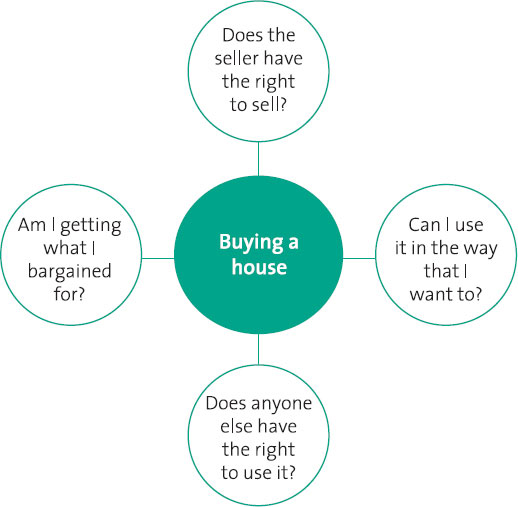

The effect of this maxim is that, unless the transaction is fraudulent, the seller is not liable for any matter concerning the property that the buyer fails to discover either at the time of their purchase or subsequently. This places firmly upon the buyer the responsibility to make sure that:

the seller has the right to sell the property;

the seller has the right to sell the property;

the property is not subject to any third party rights that might affect either its market value or the buyer’s enjoyment of it; and

the property is not subject to any third party rights that might affect either its market value or the buyer’s enjoyment of it; and

the buyer is fully aware of the property’s physical condition.

the buyer is fully aware of the property’s physical condition.

Aim Higher

The marketability and saleability of property underpins every aspect of land law. As you work through the topics in this text, try to think about how the various issues might affect the sale or purchase of a property, or the owner’s enjoyment of it. For example, a right of way across someone’s garden could affect its marketability and its value, if the right of way rendered the property less private. This will aid your understanding of the various concepts on a practical level, and how they interact.

Understanding: the modern conveyancing process

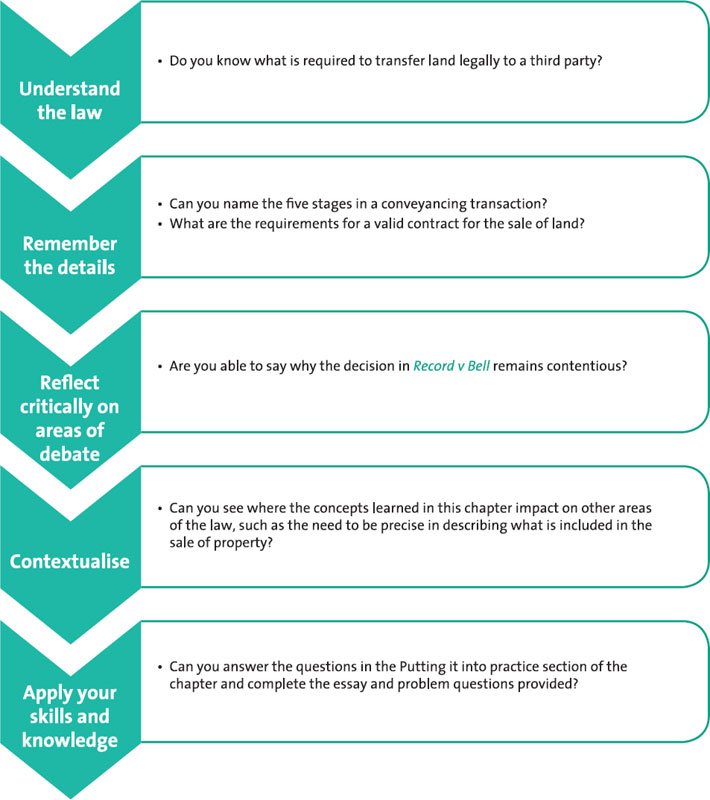

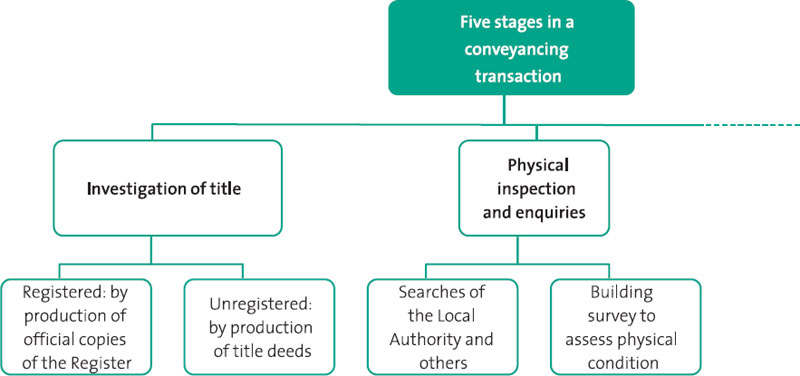

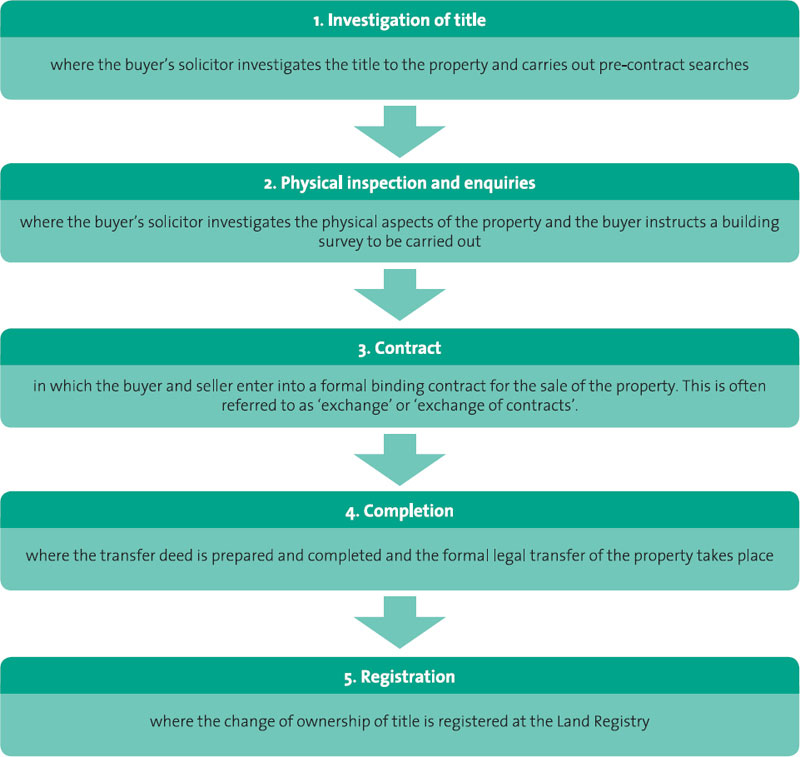

There are five basic steps in a residential conveyancing transaction:

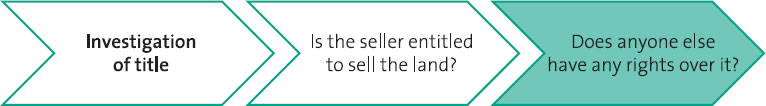

Investigation of title

Before a buyer commits to a purchase of land, they will want to be confident that the seller is the actual owner of the property and that they are entitled to sell it.

In order to establish this, the buyer will ask the seller to ‘prove their title’ to the property: in other words, to give evidence that they have the right to sell it. This is done in one of two ways:

if the property is unregistered, by evidencing through the production of successive title deeds to the property, that there is an unbroken ‘chain of ownership’ by which the property has passed from owner to another over a minimum period of 15 years, ending with the seller.

if the property is unregistered, by evidencing through the production of successive title deeds to the property, that there is an unbroken ‘chain of ownership’ by which the property has passed from owner to another over a minimum period of 15 years, ending with the seller.

Proving title in registered and unregistered land

In addition to seeking reassurance that the seller has the right to sell the land, the buyer will also want to establish whether anyone else has any rights over the land, either to use it in a certain way, or to restrict the buyer’s use of it. For example, the property may be subject to a right for third parties to graze cattle on the land, or there might be a covenant over the land, preventing the owner of the land from building on it. This would render the land useless to someone wishing to use it for the construction of their dream home.

The buyer can discover whether any such rights exist whilst checking the official copies of the register issued by the Land Registry in the case of registered land or, in the case of unregistered land, by looking at the wording in the title deeds and documents provided to them by the seller.

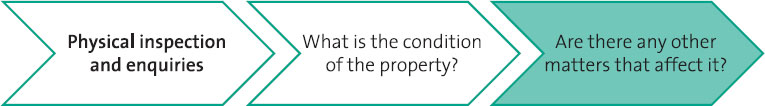

Physical inspection and enquiries

Investigating the condition of the property

Having discovered everything they wish to know regarding the legal position of the property, the buyer now needs to consider whether there is any physical aspect of the property that might make their purchase of it undesirable. Such matters would include not only the physical condition of the property itself, but also the locality within which the property lies.

The buyer will invariably carry out their own visual inspection of the property, but they may also instruct a surveyor to carry out a building survey to establish the physical condition of any buildings on the land being purchased.

Other enquiries of the seller

In addition, the buyer’s solicitor will also carry out a number of searches and enquiries to establish whether there are any other physical considerations that may affect the property’s marketability or use. These will invariably include, among others:

a search of local authority records, to discover any planning restrictions affecting the property as well as the ownership of any roads leading to the property and who is responsible for maintaining them;

a search of local authority records, to discover any planning restrictions affecting the property as well as the ownership of any roads leading to the property and who is responsible for maintaining them;

a coal mining search, to check whether there are any mine shafts on or near the land which might prove dangerous or cause subsidence to the property;

a coal mining search, to check whether there are any mine shafts on or near the land which might prove dangerous or cause subsidence to the property;

an environmental report, to make sure there is no contaminated land on or near the property; and

an environmental report, to make sure there is no contaminated land on or near the property; and

a drainage search, to check the position and maintenance of drains and sewers serving the land.

a drainage search, to check the position and maintenance of drains and sewers serving the land.

The seller’s solicitor will usually also ask some more general questions of the seller, such as whether there are any maintenance or service charges attached to the property or even whether there are any disputes with neighbours that might cause a problem. The purpose of all these enquiries is to establish whether the property is a viable property to purchase, in accordance with the buyer’s requirements.

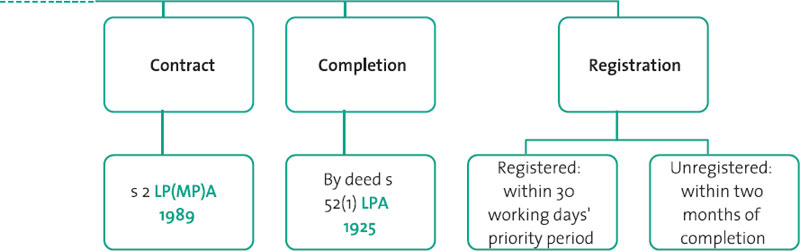

Contract

Introduction

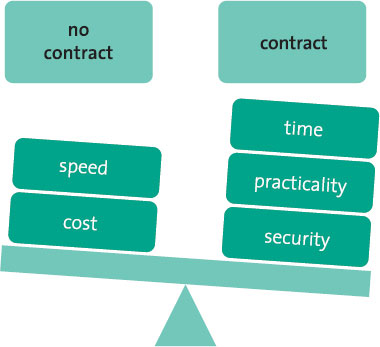

Once the title and condition of the property have been thoroughly investigated and the buyer is sure that they are happy to go ahead with their purchase, the parties will usually proceed to the contract stage of the conveyancing transaction. Entering into a binding contract for the sale and purchase of the land prior to its legal transfer is not compulsory but it is seen as standard practice, particularly in the purchase of residential property.

The reason for this is primarily a practical one: whilst it may be quicker and, in the short term, cheaper (it is usual for the buyer to pay a deposit of around 10 per cent at the point of exchange) to move directly to the transfer stage of the transaction, entering into a contract for the sale and purchase with the transfer date set at a later date gives the parties the opportunity to arrange for the transfer of services to the property, such as gas, electricity and water, and to organise removers. If they go to all this trouble without exchanging contracts first, there is in theory nothing to stop the other party pulling out of the transaction at the last minute, wasting valuable time and money on both sides.

The payment of the deposit and the threat of breach of contract, however, give both sides security and allow them to make the necessary arrangements for the transfer of the property without fear of this happening.

This is equally the case for the buyers and sellers of commercial property, who may have even more at stake than a residential purchaser. If work needs to be carried out prior to the buyers taking possession of the property, or planning permission for building works or for a change of use is required, it can be done between contract and completion, safe in the knowledge that the parties are bound to complete on the prescribed date.

The form of the contract

In order to be valid, a contract for the sale of land must comply with the provisions of s 2 of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989. The section states the following:

Section 2

(1) A contract for the sale or other disposition of an interest in land can only be made in writing and only by incorporating all the terms which the parties have expressly agreed in one document or, where contracts are exchanged, in each.

(2) The terms may be incorporated in a document either by being set out in it or by reference to some other document.

(3) The document incorporating the terms or, where contracts are exchanged, one of the documents incorporating them (but not necessarily the same one) must be signed by or on behalf of each party to the contract.

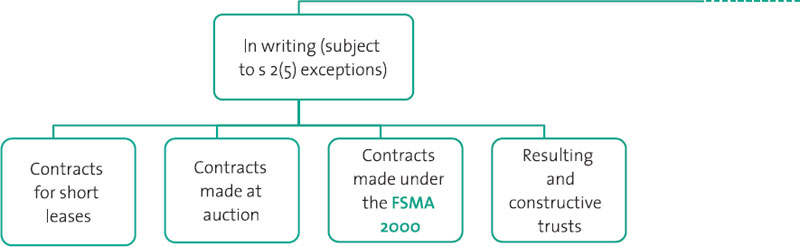

‘In writing’

Section 2(1) clearly states that a contract for the sale of land must be in writing in order to be valid. It is therefore not possible to create a contract for the sale and purchase of land orally.

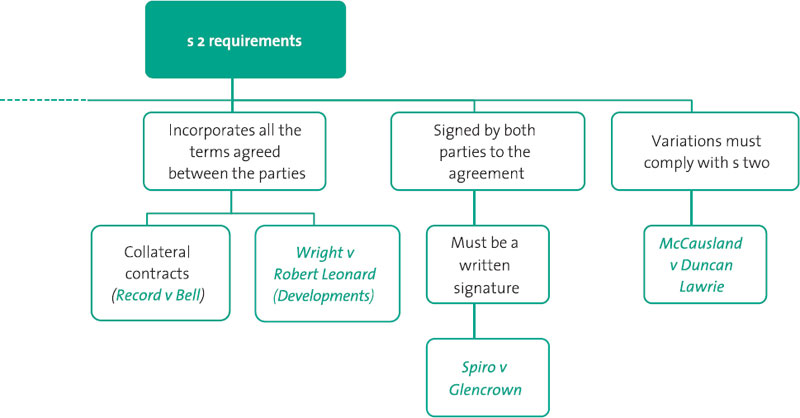

‘Incorporates all the terms’

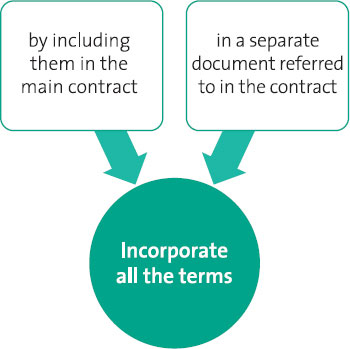

Section 2(1) also states that in order to be valid the contract must incorporate ‘all the terms which the parties have expressly agreed’. This is significant because it means that if any of the terms agreed between the buyer and seller is omitted from the contract, then the whole of that contract will be rendered void (not just the additional terms).

The easiest way to ensure that all the terms of the agreement are incorporated under s 2 is simply to include them in the contract itself. However, s 2(2) of the Act also states that the terms of the agreement may be incorporated by reference to some other document.

It is useful to be able to do this where the terms of the agreement are lengthy or where a plan is required: for example, in residential conveyancing transactions, a plan showing the boundaries of the property to be purchased is routinely attached to the contract for sale and the property described as ‘shown edged in red on the attached plan’.

Common Pitfalls

When introducing additional documents, care should be taken to ensure that they are properly incorporated into the agreement. If the contract fails to mention any additional terms agreed and documented separately, a strict interpretation of the Act would dictate that the contract would be void for failure to incorporate all its terms.

The courts have not always been strict with their interpretation, however. The two contrasting cases of Record v Bell [1991] and Wright v Robert Leonard (Developments) Ltd [1994] serve as a useful comparison:

Case precedent – Record v Bell [1991] 1 WLR 853

Facts: The parties entered into a contract for the sale and purchase of land, agreeing as a condition of completion that the sellers would produce some additional documentation. The seller produced the required documentation but the buyer refused to complete, alleging that the contract was void because it did not incorporate all the terms of the agreement. The court found in favour of the seller, stating that the agreement to produce documentation was collateral to the main contract and therefore did not have to comply with s 2.

Principle: In order to be valid, a contract for the sale of land must incorporate all the terms agreed between the parties.

Application: In a problem question scenario, use this case to support your argument that additional terms contained in a separate agreement will not render the main contract void; rather they will form a separate agreement.

Up for Debate

So why did the court find in favour of the seller in Record v Bell [1991]? By finding that the agreement to produce the additional documentation was a collateral contract, independent from the sale of land but dependent on the transaction as consideration for the agreement, the court was able to circumvent the strict requirements of the Act. The decision was not well received, however, and has not been followed in later cases.

In Wright v Robert Leonard (Developments) Ltd [1994] the Court of Appeal took a much stricter line:

Case precedent – Wright v Robert Leonard (Developments) Ltd [1994] NPC 49

Facts: A dispute arose as to what was included in the sale of the show home on a development. The buyer believed that the contents of the show home were included in the purchase. The sellers disagreed. There was no reference to the contents of the property in the contract. The court held that the contract did not comply with s 2, as it did not incorporate all the terms of the agreement and was therefore void.

Principle: In order to be valid, a contract for the sale of land must incorporate all the terms agreed between the parties.

Application:

if the property is registered, by providing an up-to-date copy of the register entries for that particular property held at the Land Registry; or

if the property is registered, by providing an up-to-date copy of the register entries for that particular property held at the Land Registry; or