Equity: Its Meaning, History and Maxims

Chapter 1

Equity: Its Meaning, History and Maxims

Chapter Contents

Our Civil Court System in the Twenty-First Century

Coming Full Circle — Back to the Twenty-First Century

Equity’s Guiding Principles — Its Maxims

As You Read

Look out for the following key issues:

How equity developed over the years, how it became discredited in the nineteenth century but how it escaped the jaws of defeat through the Supreme Court of Judicature Acts 1873 and 1875 to become even more important than ever before;

How equity developed over the years, how it became discredited in the nineteenth century but how it escaped the jaws of defeat through the Supreme Court of Judicature Acts 1873 and 1875 to become even more important than ever before;

What the term ‘equity’ means — how initially it might appear to be a vague concept involving fairness, justice and doing what is right according to good conscience but appreciate how such concepts have solidified over the centuries into principles applied today; and

What the term ‘equity’ means — how initially it might appear to be a vague concept involving fairness, justice and doing what is right according to good conscience but appreciate how such concepts have solidified over the centuries into principles applied today; and

What those guiding principles — or ‘maxims’ — of equity entail and how they operate.

What those guiding principles — or ‘maxims’ — of equity entail and how they operate.

‘Equity’ — What is it?

The word ‘equity’ has different meanings for different people. In the wider world, people talk of ‘the equity in their homes’ as meaning the surplus of money which is their own in their houses after the sum borrowed on mortgage from their lender has been repaid. In recessionary times, if the sum borrowed from the lender is more than the actual overall value of the house itself, then there is no surplus or ‘equity’ in the house, thus giving rise to the phrase ‘negative equity’. Another meaning of ‘Equity’ would be the trade union which represents performers and artists.

In this book, however, ‘equity’ is considered in a different light entirely. ‘Equity’ in our sense is derived from the Latin phrase aequitas equitas which means fairness or justice. Equity means something which might generally be considered to be positive. It means acting fairly, in good conscience, or perhaps doing what would generally be thought of as right. Doing what is ‘equitable’ is commonly understood to mean doing what is fair.

A common misconception amongst people is that the law in general does what is morally right. That is not necessarily the case. The law largely provides functionality to situations ensuring, for instance, that contracts are entered into and upheld or that people are punished after committing a criminal offence. Morality may or may not be part of the law as a whole, but it forms part of equity.

Equity in practice

Take an example of equity’s operation in the real world. Today, there are two key instances of where equity operates:

[a] the trust; and

[b] in offering bespoke remedies to the legal system.1

The common law gives the builder a remedy. In reality, though, it might not be that useful for the builder. He is the entirely innocent party. To sue you for damages, he will need to re-market the house and sue you only for the difference between the amount he would have received from you had you proceeded with the purchase and the (lower) amount he actually achieved on another sale after you had pulled out. The builder can only sue you for the main loss he has sustained together with other, subsidiary, consequential losses.

However, it seems unfair that the builder should have to market the property again and wait until he can receive his money given that he has done nothing wrong. In this case, equity may come to the assistance of the builder. Equity can provide another remedy to the builder: that of specific performance.

Glossary: Specific performance

This is a court order which ensures that a defaulting party must adhere to the terms of a contract that they have entered into. Such an order is usually only given when the subject matter of the contract has a unique identity — for example, where a contract concerns a piece of land. See Chapter 17 for a detailed discussion of this equitable remedy.

The equitable remedy of specific performance will mean that the court can compel you to buy the house from the builder. The builder asks the court for an order stating that you must specifically perform the contract. If such an order is given, then you must go ahead and buy the property.

Arguably, this equitable remedy of specific performance is fairer to the builder. It is prob-ably objectively fairer to the entire situation, since it is right that you are made to go ahead with a contract into which you freely entered.

What this example shows is that:

[a] the remedy equity provides can give a fairer result than the law;

[b] equity is far more flexible than the law and its remedies are capable of tailoring themselves to specific situations. The common law is comparatively inflexible, taking more of a ‘broad brush’ approach to all situations. Damages in this example will suffice for the builder as after all, they do give him a remedy. But equity is more akin to a made-to-measure suit than the answer which the law gives, which is more off-the-peg in that it will fit the vast majority of situations before it. Specific performance in our example is a bespoke remedy which is capable of giving the innocent party exactly what they want, whilst making sure the defaulting party is no worse off than under the original agreement that they entered into; and

[c] equity can be seen to be grafted upon the law. More than this, it takes precedence over the law in certain situations. The remedy the law gives is similar to watching a movie in 3-D without the special glasses. You will still see the ‘gist’ of the movie, but you will not really understand it or see it all. Equity is the equivalent of putting the glasses on. Suddenly a more rounded view is brought into focus. It enables you to see everything clearly and takes into account all of the subtleties in the film. It is the same with equity: equity can take into account the subtleties in the case and award an appropriate remedy.

To understand why equity in our context means fairness and why it is capable of providing bespoke remedies, it must be understood how equity developed into such an important legal concept.

Our Civil Court System in the Twenty-First Century

The court system in England and Wales has been shaken up in recent years. The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 created a new Supreme Court for the United Kingdom.2 This new court replaced the House of Lords as the highest appellate court. It heard its first case in October 2009.

Making connections

One of the reasons for abolishing the House of Lords (as the forerunner of the Supreme Court) was that not only did its members decide important cases which had reached the highest appellate court but those same Law Lords could also take part in debates which led to the enactment of legislation.3 There was, therefore, a potential conflict of interest as the same set of people were both making the law and deciding on its interpretation. This arguably offended the separation of powers of the legislature and the judiciary.

Although, by convention, the Law Lords did not take part in political debates in the House of Lords during its law-making processes, they were permitted to speak out on matters if giving their own personal views.

To avoid any possible conflicts of interest, the government decided to establish an entirely separate final court of appeal, called the ‘Supreme Court’. The Law Lords would hear final appeals in that court and would no longer take part in debates in the House of Lords.

Below the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal retains its appellate jurisdiction, hearing civil appeals from both the county court and the High Court. These last two are, of course, courts of first instance.

What is important for our purposes, however, is the system of law that the courts currently apply. As seen in the example with the building contract,4 the courts apply both law and equity to determine the outcome of cases. Ultimately equity can take precedence over the law. Yet the important point remains that nowadays we have one combined system of ‘law’ in general terms comprising both common law and equity. The courts apply whichever system gives the most appropriate result.

This combined system is a relatively recent development. In order to understand how the courts have this ability, we need to take a look back at the historical development of equity.

History of Equity

Stepping back in time — the development of the common law

1066. The year, for most people, is significant as being the year in which William of Normandy defeated King Harold at the battle of Hastings. What happened in the years following the battle was the spread of what is known as the ‘common law’.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

Students traditionally nowadays think of the phrase ‘common law’ as meaning law made by the judges (i.e. law which is not made by Parliament).

Originally, however, ‘common law’ meant law which was common across the country. Common law was encouraged by William the Conqueror as a means of ensuring that the whole country was subject to the same laws. It was a way of unifying the country and ensuring that the monarch kept control.

The development of the court structure through the Middle Ages cannot be set out precisely. It is hard to pin down exactly when each court was set up since ‘court’ is not an easily definable term.5

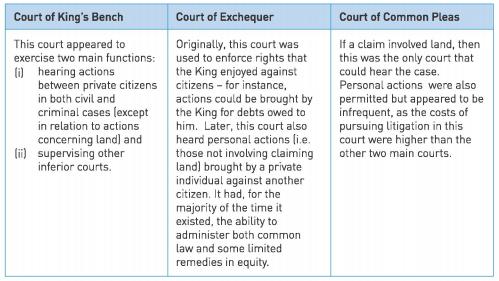

Aside from a system of local courts, what we can say is that, probably by the thirteenth century,6 three main courts, trying common law matters, were established in Westminster, London: the Court of King’s Bench, the Court of Exchequer and the Court of Common Pleas. These are detailed in Figure 1.1 below, although there appears to have been a great deal of overlap of the subject matter dealt with by each court.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

The original Exchequer was established by the reign of Henry III (1216–1272) with two main functions: (i) a financial office and (ii) a court.7 Later, the two functions would be separated into the two distinct entities that would form part of what we know today as HM Treasury and the court system of England and Wales.

The courts trying common law matters had therefore been in existence for roughly 600 years until their abolition by the Supreme Court of Judicature Acts of 1873 and 1875.

Beneath the surface of the common law courts, however, lay a number of problems. These took the form of:

[a] the procedure for initiating an action; and

[b] the use of juries in deciding facts in an action.

Procedural defects with the common law courts

The main form of commencing an action against another party was by issuing a writ.

Glossary: A writ

This was a formal document that was used by a claimant to start a case. Though it changed in form and content over the centuries, it was only abolished comparatively recently, by the Civil Procedure Rules 1998. It was replaced by the ‘claim form’ which remains in use today.

Writs were issued by a common law court. The objective of issuing a writ was to ensure that defendants came to court to hear the case against them. The common law had a rather harsh way of ensuring that occurred, however. To give an example with regard to an action for land, if the defendant did not appear before the court, his land would be seized for the King; if he still did not appear, then the land would be given to the claimant.8 In other claims, it appears that the defendant could be arrested if he did not voluntarily attend the court.

That was not the only difficulty with writs, however. Lawyers, even today, like to use precedents — or templates — before they draft any document. It gives a practising lawyer a sense of security that someone before them has drafted a similar document. At the time of Henry III, there were ‘some thirty or forty’ types of writ in use but there were ‘large differences’ between them9 so that the total number of writs in use could have been in the hundreds. This may not have been a bad system in itself, given lawyers’ fondness for precedents, but the Provisions of Oxford, issued in 1258, specified that no writ could be issued unless the case followed a writ that had previously been issued. This meant that a party whose case was substantially different from a previous case could not make use of the common law to help them find a remedy, given the need to find a former writ to start the action. It could mean that a party was effectively remedy-less, which is hardly a fit state for the law to be in!

In addition, two causes of action could not be contained within the same writ: there had to be separate writs. This invariably added expense for the party who wished to start an action.

The use of juries in deciding facts in an action

The use of juries became more common in civil actions from the thirteenth century onwards. Trial by jury has practically been abolished in civil matters today. The main danger of trial by jury was the lack of certainty in the outcome, especially as it was possible for members of juries to be bribed, cajoled or threatened into finding certain facts in favour of one of the parties.

The end result of these difficulties was delay. Frustration no doubt followed on the part of not only claimants but also defendants. Even if the claimant’s case was eventually heard and he was successful, the remedy he had to accept was given from the common law. As the example of the building contract shows,10 the successful claimant might not necessarily want a common law remedy but might instead want a more specific remedy, tailored to his needs.

Fortunately, a separate system also existed and worked alongside the common law, to mitigate its harsh effects. That was the system of equity.

Stepping back in time — the development of the court of equity

Following the Norman Conquest and even by the thirteenth century, there was no separate court which simply administered equitable principles of fairness and doing what was right according to good conscience. The main courts were able to dispense justice as they saw fit. Most times, this would lead to a result which was derived from the common law, but the courts had the ability to give an equitable result if they felt it right to do so.

If the common law was unable to grant a remedy, however,11 claimants had another avenue available to them. The claimant could petition — or ask — the King directly. The King could grant relief even if the common law was unable to assist. The courts were the courts of the King and he could step in to grant a remedy when his courts did not.

History illustrates, however, that English Kings had more pressing matters to deal with than petitions from their subjects. These other matters of both domestic and foreign policy were time-consuming. It no doubt became impractical for the King himself to deal with petitions from his subjects and so, gradually, he transferred the responsibility of dealing with the petitions to his Chancellor. Edward III’s Order of 1349 to this effect regularised this procedure for the first time.

Glossary: The Chancellor

The Chancellor was the most important of the King’s ministers. The Chancellor was the head of Chancery. Two of the most famous Chancellors in history, Thomas Wolsey (who was Chancellor 1515–1529) and Sir Thomas More (Chancellor 1529–1532), both of Henry VIII’s reign, effectively ran the country’s entire domestic policy and aspects of foreign policy as well as the Chancery.

Nowadays, the Chancellor is head of the Chancery Division of the High Court.

Chancery as an institution was not originally a court. It has been described as ‘a great secretarial bureau, a home office, a foreign office and a ministry of justice’.12 Originally, the Chancery issued its own writs, called ‘original’ writs, but these developed a more informal slant as it grew used to dealing with petitions to the King. Over time, the Chancellor gained his own court, called the Court of Chancery. This court had been established long before Wolsey’s time. It was in this court that the Chancellor considered the petitions sent to him.

How did the Chancellor decide upon matters presented to him? It seems that by the time of More as Chancellor, decisions of the Chancellor and the court were made according to matters of ‘conscience’ since the role of the Chancellor was that of the ‘keeper of the King’s conscience’ due to early Chancellors being members of the clergy. The Chancellor did what he thought was objectively the right thing to do. He applied rules of equity.

Moreover, decisions could be based on conscience because the Court of Chancery was the only court to examine the parties on oath.13 It was, consequently, thought that since evidence was effectively a product of someone’s conscience — since their conscience would govern what they said in court — the decision given to them could similarly be based on conscience.

The Chancery Commissioners‘ Report of 182614 gave examples of the Court of Chancery’s equitable jurisdiction concerning, amongst other matters:

[a] managing trusts;

[b] managing the powers of disposing property by will or the laws of intestacy through the control of personal representatives; and

[c] providing more bespoke remedies in actions where the common law could not assist, such as the remedy of specific performance.

Equity’s fall from grace

As described above, equity sounds like a good idea in theory. The principle that a claimant’s legal problem can be resolved according to good conscience creates a nice, warm feeling. It also, in theory at least, leads to the right result in a case. That, coupled with the concept that a relatively informal procedure can be applied — of petitioning the King or his Chancellor — in order to obtain a remedy, should lead to a highly flexible system of justice, capable of responding to all types of legal case.

Arguably, for the first few centuries of the existence of the Court of Chancery, the court applied its equitable principles in a flexible manner. This approach was summarised by John Selden as ‘being as variable as the length of each Chancellor’s foot’.15 His expression clearly meant that equity was not a fixed concept.

Yet the point of having a flexible system implies that it must be used in a malleable manner. Applying equitable principles in a flexible manner can be good, but it rests on the assumption that the person who is Chancellor is content to adopt such an approach. Lord Eldon is arguably the best example of a Chancellor who was not content to apply equitable principles flexibly. He was Chancellor from 1801–1827 and was proud of the fact that:

The doctrines of this Court ought to be as well settled and made as uniform almost as those of the common law, laying down fixed principles. … I cannot agree that the doctrines of this Court are to be changed with every succeeding judge. Nothing would inflict on me greater pain, in quitting this place, than the recollection that I had done any thing to justify the reproach that the Equity of this Court varies like the Chancellor’s foot.16

In addition, the background of Chancellors began to change after Wolsey. They no longer tended to have a church background, but instead, most of them were lawyers. As mentioned above, English lawyers to this day tend to like precedents but, from Ellesmere to Eldon, Chancellors used it to the disadvantage of equity. As a consequence, the flexibility at the heart of equity began to be eroded, and was replaced by the certainty of applying the same principles in each case.

The inflexible, rigid application of applying fixed principles to cases by the nineteenth century had other consequences. Delays in cases became notorious in the Court of Chancery as successive Chancellors grappled with applying increasingly fixed principles to the varying facts of each case. With delays came additional expenses for the litigating parties, as their lawyers were linked to the case for longer periods of time. This became well known, so much so that Charles Dickens wrote Bleak House, which focused on the delays in the Court of Chancery in his fictional case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce. Indeed, Dickens describes the Court of Chancery as being the ‘shining subject of much popular prejudice’ and whilst the case in his book was fictional, his preface gives an example of a real-life case:

there is a suit before the Court that was commenced nearly twenty years ago; in which from thirty to forty counsel have been known to appear at one time; in which costs have been incurred to the amount of seventy thousand pounds … and which is (I am assured) no nearer to its termination now than when it was begun.17

That having been said, however, it is probably worth mentioning that not everyone thought that delays in court were a bad thing. The Report of the Chancery Commissioners in 1826 acknowledged that the court had been subjected to criticisms of delay, but said that the notion of delay had been ‘so frequently misapplied, as to convey a very incorrect idea’. The Report even went on to say that delay could be useful in some situations, such as in applications for dealing with the property of children under a trust:

It is obvious that, in the common case of bills filed for the protection of the property of infants, the suit must last until such infants attain their ages of 21 years (i.e. until the infant reached the age of majority, where they could take the property themselves).18

It is interesting to note that the chair of the Chancery Commissioners was none other than Lord Eldon!

Applying fixed principles was not the only cause of the delay. The actual procedure which governed the mechanics of the workings of the Court of Chancery was effectively broken too. From commencing a case in the Court of Chancery until after judgment was given, the system in the nineteenth century was far harder than it should have been.

From petitioning the King as a relatively informal process which avoided the more formal requirements of the common law writ, the start of an action in Chancery had developed into the need for the claimant to draft a rather complex bill to the Chancellor. In Manchester’s view, the bill ‘consisted of nine parts and was of an impressive length’.19