Equitable Remedies and Proprietary Estoppel

Chapter 17

Equitable Remedies and Proprietary Estoppel

Chapter Contents

As You Read

Look out for the following issues:

the nature of the general remedies that equity offers and how they each achieve a different objective;

the nature of the general remedies that equity offers and how they each achieve a different objective;

tthe ingredients required to establish a successful claim in proprietary estoppel; and

tthe ingredients required to establish a successful claim in proprietary estoppel; and

tthe flexibility of proprietary estoppel in offering a range of remedies should a claimant establish a successful cause of action.

tthe flexibility of proprietary estoppel in offering a range of remedies should a claimant establish a successful cause of action.

Equitable Remedies

The common law offered a ‘rough and ready’ remedy for a successful claimant: damages. This remedy continues to this day so that, for example, a claimant suing for breach of contract will be awarded damages with the aim of placing him in the position he should have been in had the contract been honoured and not breached.1 The common law remedy of damages is, of course, good for providing compensation to right a wrong, but it is a poor remedy to try to pre-empt a wrong from initially occurring.

Equity developed a number of different remedies which are designed to be proactive instead of reactive, as damages at common law. Moreover, equitable remedies attempt to give the claimant a more tailored remedy than common law damages. As Lord Selbourne LC put it in Wilson v Northampton & Banbury Junction Railway Company,2 equitable remedies exist ‘to do more perfect and complete justice’ than common law damages.

Equitable remedies are only available at the court’s discretion and to claim an equitable remedy, the claimant must show that common law damages will not be an adequate remedy in their own right. Equity, of course, also developed its own version of damages, called equitable compensation, but this has been discussed in Chapter 12 and will not be considered further here.

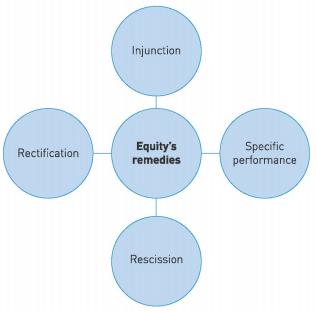

The remedies equity offers are illustrated in Figure 17.1 (overleaf).

Each of these remedies must be considered.

Injunction

There are five main types of injunction: prohibitory, mandatory, quia timet, search orders and freezing orders. All can be awarded on an interim or a permanent basis.

An interim (formerly ‘interlocutory’) injunction is awarded before the main trial of the claim occurs and, as such, is of a temporary nature. If an interim injunction is to be granted, the court will require an undertaking from the claimant that (i) he will pay the defendant damages if it turns out at trial that the claimant had no basis to restrain the defendant by way

of an injunction and (ii) as a result of the injunction being granted, the defendant has suffered loss. In American Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd,3 Lord Diplock said the court was always trying to balance two competing interests in awarding an interim injunction:

[a]the protection the claimant needed and which would not be compensated adequately by the award of damages at a later trial; and

[b]the fact that granting an interim injunction deprived the defendant of being able to exercise his legal rights (by, say, continuing to trade in a particular product) which would not be adequately compensated by the claimant’s undertaking to pay him damages if the defendant were to be successful at trial.

A permanent injunction, as the name suggests, is of a permanent nature and is awarded to a successful claimant after a trial of the claim.

An injunction is used to enforce a legal or equitable right. As Lord Denning MR said in Mareva Compania Naviera SA v International Bulkcarriers SA; The Mareva,4 ‘[t]he court will not grant an injunction to protect a person who has no legal or equitable right whatever’.

Prohibitory injunction

A prohibitory injunction is designed to prevent a party from undertaking an action. This type of injunction was considered by Lord Diplock in American Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd5. The case concerned a patent.

Glossary — A patent

A patent is a term from the law relating to intellectual property. If you hold a patent, you enjoy a period of time in which you have the monopoly over your invention. No-one else may compete directly with you and market a copy of your hopefully lucrative invention.

The claimant company had the benefit of a patent over a type of surgical suture. The defendant company was in the process of launching a competitor suture into the British market. The claimant sought an interim injunction preventing it from doing so, claiming that the defendant’s suture infringed its patent. The High Court awarded the injunction, but the Court of Appeal reversed it, holding that the claimant’s patent had not been infringed. The claimant appealed to the House of Lords. The House of Lords granted the injunction.

The only substantive opinion was delivered by Lord Diplock. He said that in deciding to grant an interim injunction, the court had to be satisfied that ‘the claim is not frivolous or vexatious, in other words, that there is a serious question to be tried’.6 The court should go no further than this: in particular, the court’s task was not to try to decide which party would succeed at trial as this involved relying on untested witness statements.

Provided the court was satisfied that there was a ‘serious question to be tried’, the court then had to consider whether the ‘balance of convenience’7 meant that the injunction should be granted or refused. Lord Diplock set out the following two principles:

[a]if it seemed that the claimant would succeed at trial but damages would compensate him adequately, the injunction should be refused; but

[b] if damages would not be an adequate remedy, but it seemed likely that the defendant would succeed at trial and be adequately compensated by the claimant’s undertaking to pay him damages, the court should normally grant the injunction.

The key to these principles is whether damages would be an adequate remedy for the claimant at trial. If damages are an adequate remedy, no injunction should be awarded. Conversely, if they are not, the injunction should be granted.

If the court was in doubt as to whether damages were an adequate remedy, the ‘balance of convenience’ test applied. One party was, of course, always liable to suffer disadvantages from an interim injunction being granted. The extent of the disadvantages suffered were a ‘significant factor’8 in deciding where the balance of convenience lay over whether or not to grant the injunction. The court could, provided the parties‘ arguments over the extent of their disadvan-tages were equal, take into account how strong each of their arguments were in each party’s witness statements. But the court was to go no further than this and, particularly, was not conduct a trial of the action.

The trial judge had taken into account such factors that the defendant’s sutures were not yet in the UK market and they had no ongoing business that an interim injunction would prevent from continuing. This meant that the granting of an injunction against the defendant would not mean factories closing and a workforce being denied employment. The claimant was in the process of establishing a growing market in the UK of this particular type of suture. Had the defendant been able to market its product before the trial of the action to ascertain if the patent had been infringed, the claimant’s opportunity to take a share of that market would have been stunted. These factors indicated that, on the balance of convenience, the trial judge’s injunction should be restored.

Although the case concerned an interim injunction, many of Lord Diplock’s views may apply equally to a permanent injunction. The key test must surely be the same for both types of prohibitory injunction: Are damages a remedy that will adequately compensate the claimant? If not, the injunction should be granted; if they are, the injunction should be refused.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

The injunction, especially the prohibitory injunction, has been much in the news recently, due to the rise of the so-called ‘super-injunction’. The grant of such an injunction is usually requested by well-known celebrities to prevent the press from publishing stories about them. The injunctions have been termed ‘super-injunctions’ because the court has, on occasions, restricted the press from reporting which celebrity has been granted an injunction and the subject-matter of the injunction. Well-known celebrities who have had super injunctions granted in their favour include the footballer Ryan Giggs and the TV personality Jeremy Clarkson.

The danger with super-injunctions is, of course, that they infringe the free reporting of legal news stories and, due to the fact that a claimant must give an undertaking to pay damages, are restricted to the wealthy who can afford to give such an undertaking.

Do you think that the super-injunction is really an example of a ‘sledge-hammer to crack a nut’?

Mandatory injunction

A mandatory injunction compels performance of an obligation. A comparison between prohibitory and mandatory injunctions, together with interim and final injunctions, was made by Megarry J in Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham.9

The claimant had built a large number of houses in Caerphilly, South Wales. The estate was laid out in an ‘open plan’ style, which meant that each house owner had covenanted not to construct a fence, or any other erection, in front of the building line of each house. The problem was that Welsh mountain sheep and horses began to graze in the gardens of the properties. The defendant constructed a fence to prevent this occurring. The claimant sought an injunction to compel the defendant to remove the fence. The injunction sought was of a mandatory nature because it would have forced the defendant to comply with the obligation he had entered into not to construct a fence.

Megarry J refused to grant the injunction. This was largely due to the fact that the claimant had delayed for four months after issuing his claim before seeking the interim injunction it required. This suggested that even the claimant thought that the matter was not of an urgent nature.

Megarry J distinguished between prohibitory and mandatory injunctions. The latter were harder to obtain. The very nature of a mandatory injunction meant that it was used to correct what had happened in the past, so inflicting an additional cost on a defendant in having to take steps to undo his previous actions. A prohibitory injunction looked to the future: it sought to prevent future conduct from occurring and so imposed no cost onto a defendant to undo actions he had previously undertaken.

There were also theoretical differences between mandatory and prohibitory injunctions. A mandatory injunction obliged a defendant to carry out positive steps; a prohibitory injunction was an order to refrain from continuing an activity.

Megarry J said that in deciding whether or not to grant a mandatory injunction, the court would assess whether granting the injunction produced a ‘fair result’.10 The court would take into account how trivial the damage was to the claimant seeking the injunction, the detriment granting it would have on the defendant, as well as the benefit the claimant would gain from having the injunction granted. The general principle was that it was far harder to obtain a mandatory than a prohibitory injunction.

Further differences could be made between interim and final injunctions. Megarry J made the following points about an interim injunction:

[a]an interim injunction ‘for a mandatory injunction was one of the rarest cases that occurred’;11

[b]the case ‘had to be unusually strong and clear before a mandatory injunction will be granted’.12 That was because the court had to take into account that the injunction may not be awarded following a full trial of the claimant’s claim;

[c]before granting the interim mandatory injunction, the court had to ‘feel a high degree of assurance that at trial it will appear that the injunction was rightly granted’;13 and

[d]if an interim mandatory injunction was granted, it would not usually be extended at trial, as by then the defendant will have been ordered to take a particular step which, by the stage of trial, he should have normally taken. In contrast, a prohibitory injunction would usually be continued at trial for there would still be a purpose in preventing the defendant from continuing with his behaviour.

An injunction will not be granted where its effect would be to grant an order of specific performance if the court could not validly grant that order of specific performance. For example, specific performance will not be ordered to enforce a contract for personal services,14 as was shown in Page One Records Ltd v Britton.15

Here a pop group called ‘The Troggs’ engaged the claimant as their manager. Approximately two years later, the group sought to dismiss the claimant as their manager and appoint another manager in its place. The group’s argument was that the manager had breached its fiduciary duties to the group. The claimant applied for a mandatory injunction to compel the group to honour the contract between them (and, therefore, to prevent the group from using the services of the other manager) which was to last for a further three years.

Stamp J refused to grant the injunction. His judgment shows a lack of general sympathy with the group. In fact, the group had not demonstrated even a prima facie case that the manager had breached its contract. It was, in fact, likely that the claimant would have a successful claim for damages against the group for wrongfully terminating the contract between them. But that did not mean that the claimant could also claim a mandatory injunction.

The comments by Megarry J in Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham, together with the decision in Page One Records Ltd v Britton, provide a useful analysis of the court’s approach to mandatory and prohibitory injunctions. A mandatory injunction seems to be a rarely sighted creature, mostly due to the fact that its very nature imposes on the defendant a cost of undoing actions that he has already taken. The court is, in addition, wary of granting interim mandatory injunctions when the defendant may well succeed at trial of defending the claim for the injunction. It is unfair to compel a defendant to incur the additional costs of undoing his actions when he may successfully defend such a claim at trial.

Quia timet injunction

This Latin phrase means ‘because he fears’. This type of injunction is granted because the claimant can show that he fears that the defendant will take a particular course of action. An injunction to this effect was upheld by the Supreme Court in Secretary of State for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs v Meier.16

The defendants were travellers who occupied part of Hethfelton Wood, Dorset. The wood belonged to the Forestry Commission. The Forestry Commission sought a possession order to repossess the wood from the travellers, together with an injunction preventing them from returning to the wood to occupy it again.

The Supreme Court upheld the decision of the majority in the Court of Appeal to grant the injunction against the travellers returning to the wood. As Lord Neuberger MR put it:

where a trespass to the claimant’s property is threatened, and particularly where a trespass is being committed, and has been committed in the past, by the defendant, an injunction to restrain the threatened trespass would, in the absence of good reasons to the contrary, appear to be appropriate.17

The court, thought Lord Neuberger MR, was not bound not to grant the injunction simply because it believed that the injunction was unlikely to be enforced if it was breached. It was, he said, likely in this case that the two usual methods of enforcing the breach of an injunction — the seizing of the defendant’s property and/or the imprisonment of the defendant — were unlikely to happen here. That is because the defendants were unlikely to have significant assets and given that a number of defendants had young dependent children, imprisonment could be seen to be disproportionate to the breaking of the injunction. Nonetheless, this did not mean that the injunction had to be refused. The court could still take the view that the defendants would be more likely to refrain from further trespasses if the injunction was granted. The injunction might, in any event, act as a deterrent to the defendant from trespassing onto the claimant’s land as they might be afraid of being imprisoned if they breached the injunction.

Of course, the problem with this injunction was that it was likely that the court would not know the identities of some of the trespassers. This caused no difficulty for the Supreme Court.Lord Rodger, in particular, disagreed with the earlier view of Wilson J in Secretary of State for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs v Drury18 that the injunction would be ‘useless’ as you could not ask the court to imprison a ‘probably changing group of not easily identifiable travellers’. There was no evidence here that an injunction against a potentially changing group would fail to work. It could be effectively served upon them, by being displayed in the wood, for example, so they would know about it.

Search orders (formerly Anton Piller orders)

This type of injunction enables a claimant to enter a defendant’s premises and search for documents if the claimant believes the defendant might destroy the documents before trial. This type of injunction was recognised by the Court of Appeal in Anton Piller KG v Manufacturing Processes Ltd.19

The claimant was a German company who manufactured computer components. The defendant was their English agent. It transpired that the defendant intended to disclose confidential information to two competitors of the claimant. The claimant sought an interim injunction to prevent this from occurring. They also sought an order permitting them to enter into the defendant’s premises, search for incriminating documents that they feared the defendant would destroy before trial and seize such material. The Court of Appeal granted the injunction and granted permission for the claimant to enter the defendant’s premises.

Lord Denning MR pointed out that the court’s order might look like a ‘search warrant in disguise’,20 but was at pains to explain that no court could grant an order which permitted a person to force their way into another’s premises without the latter’s consent. Instead, the order allowed the claimant to enter into the defendant’s premises. The defendant could refuse to give his permission to such an entry or could challenge the validity of the court order. If the order had been validly granted, the defendant risked being held in contempt of court for failing to comply with it.

Safeguards had to be applied when the claimant executed the court’s order. When serving the order on the defendant, the claimant had to be accompanied by his solicitor who, as an officer of the court, could ensure that the order was correctly executed. The defendant should be given the chance to consider the order and to take legal advice upon it. If the defendant refused permission to allow the claimant to enter his premises, the claimant could not force his way in.

Such an order as was granted in the case should only be made, according to Ormrod LJ, when three criteria are satisfied:

First, there must be an extremely strong prima facie case. Secondly, the damage, potential or actual, must be very serious for the applicant. Thirdly, there must be clear evidence that the defendants have in their possession incriminating documents or things, and that there is a real possibility that they may destroy such material before any application inter partes can be made.21

The Anton Piller order, then, is a temporary order requested by one party without notice to the other, to enter their premises, search for incriminating documents and seize them before the actual trial of the action occurs.

The essence of the Anton Piller order is now embodied in s 7 of the Civil Procedure Act 1997. The High Court may make an order permitting a party to enter into premises for the purposes of searching for evidence or to make a copy, photograph, sample or other record of such evidence.22 Whilst this is a statutory right enjoyed by claimants, it appears to leave the original Anton Piller order untouched.

Freezing orders (formerly Mareva injunctions)

Freezing orders are designed to prevent a party from dealing with his assets so as to prevent the other party from claiming them. As such, this is a type of interim injunction. It is granted to the claimant to prevent the defendant from dissipating his assets before the trial of the action can be heard. It is designed to stop the defendant from frustrating the litigation that the claimant is about to pursue.

The leading case remains the decision of the Court of Appeal in Mareva Compania Naviera SA v International Bulkcarriers SA; The Mareva.23

The facts concerned the charter of a ship, The Mareva. The claimant owners chartered it to the defendants. The defendants themselves sub-chartered it to the President of India. The President duly paid the charter fee to the defendants. The defendants, in turn, paid some of their charter fee but not all of it. The claimant claimed the unpaid part of the charter fee ( 30,800) together with damages for wrongful repudiation of the contract. The defendant had retained a sizeable sum in its bank in London and the claimant sought an interim injunction preventing the defendant from disposing of that money.

30,800) together with damages for wrongful repudiation of the contract. The defendant had retained a sizeable sum in its bank in London and the claimant sought an interim injunction preventing the defendant from disposing of that money.

Lord Denning MR held that the court had a very wide right to grant an injunction. This included applying for an interim injunction to force the defendant to retain money even though the claimant had not established that he was actually entitled to the money at trial. Lord Denning MR explained the injunction as follows:

If it appears that the debt is due and owing, and there is a danger that the debtor may dispose of his assets so as to defeat it before judgment, the court has jurisdiction in a proper case to grant an [interim] judgment so as to prevent him disposing of those assets.24

This was a ‘proper case’ for the injunction to be granted. The charterers had their money in a bank and they could have moved it to another country at any point, making it highly unlikely that, in practical terms, the owners would be able to recover the money owed to them. The injunction would be granted until a full trial of the claimant’s claim took place.

Since the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 came into effect, Mareva injunctions have been known as ‘freezing orders’. Rule 25.1(f) of the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 specifically provides that the court may now make a freezing order which has the effect of:

[a]restraining a party from removing from the jurisdiction assets located there; or

[b] restraining a party from dealing with any assets whether located within the jurisdiction or not.

This rule makes it clear that such an order can apply to assets even if they are not located within the jurisdiction. The extension of a Mareva injunction to assets located outside of the jurisdiction of the court25 was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Derby & Co Ltd v Weldon (Nos 3 and 4).26 There the Court of Appeal held that it was not a prerequisite to the granting of a Mareva injunction that the defendant had to have assets within the jurisdiction.

The claimant alleged that the defendant had defrauded it in dealings in the cocoa market. At first instance, Sir Nicholas Browne-Wilkinson V-C had granted a worldwide Mareva injunction against a Luxembourg-based company defendant, but had refused to grant such an injunction against a Panamanian defendant. Neither company had any assets within the jurisdiction of the court. But Browne-Wilkinson VC believed that a Mareva injunction could ultimately be enforced under the European Convention on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters27 against the Luxembourg company, but there was no effective enforcement mechanism against the Panamanian company.

Lord Donaldson MR held that a Mareva injunction could be granted against foreign defendants and should be granted against both foreign defendants in this case. In deciding whether to grant a Mareva injunction, whether or not that injunction could be enforced abroad was not the primary consideration for the court. The essential point was that if a defendant refused to honour the Mareva injunction, he could be denied the right to defend the claimant’s claim at trial. This in itself was an effective enforcement mechanism against a defendant. Neither was it relevant that a defendant may have no assets. A Mareva injunction operated in personam against the defendant personally, so it was appropriate that it could be made against the defendant wherever he was in the world.

A freezing order may now, therefore, be made against a defendant who has assets located anywhere in the world. Indeed, the order would also seemingly apply against a defendant who appears to have no assets (although, if the claimant knows this, it is difficult to see why the claimant would seek the injunction initially).

Guidance as to when the court should permit a worldwide freezing order to be enforced was given by the Court of Appeal in Dadourian Group International Inc v Simms28 (these are known as the Dadourian guidelines). In delivering the judgment of the court, Arden LJ thought that there were eight guidelines that the court should take into account. These are:

[i]the granting of permission to enforce a worldwide freezing order should be ‘just and convenient’29 to ensure the worldwide freezing order is effective. In addition, it must be oppressive to the parties in the English proceedings or to third parties who might be joined into proceedings abroad;

[ii]the court needs to consider all relevant circumstances and options;

[iii]the court should balance the claimant’s interests with those of the other parties to the proceedings, including any party likely to be joined in the foreign proceedings;

[iv]the court should normally withhold its permission i f the claimant would obtain a better remedy in the foreign court than in Enland;

[v]the claimant’s evidence in support of his application should contain all necessary information to enable the court to make an ‘informed’30 decision. This would, for example, include evidence as to the law and practice of the foreign court;

[vi]the standard of proof required was that the claimant must show that there was a ‘real prospect’31 of assets existing within the foreign court’s jurisdiction;

[vii]there usually had to be a risk that the assets might be dissipated; and

[viii]usually the claimant should notify the defendant that he intended to seek the enforcement of the worldwide freezing order but in urgent cases, this could be omitted. In such a case, the defendant should be allowed the ‘earliest practicable opportunity’32 to have the matter reconsidered by the court.

These guidelines were not, as Arden LJ made clear at the end of her judgment, an exhaustive list. The court should consider any other issue which needed consideration in an individual case.

Specific performance

Specific performance is an order of the court to one party to a contract that it must adhere to the terms of a contract. An order for specific performance will be rarely granted, as normally damages at common law will be an adequate remedy in the event that the contract is breached. The claimant must show that damages are not an adequate remedy to invoke equity’s jurisdiction to grant an order for specific performance. To do that, the claimant usually has to show that the contract concerns unique property, where the payment of damages cannot adequately compensate the claimant for the defendant’s breach of contract.

As a general rule, an order for specific performance will not be granted if the court’s constant supervision is required in monitoring whether the order is implemented by the defendant: Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd.33

The defendant traded as ‘Safeway’ and had a supermarket in the Hillsborough Shopping Centre, Sheffield. The claimant was its landlord. The 35-year lease provided that the defendant would keep the supermarket open. Safeway operated the leading store in the shopping centre to which customers would be drawn. It was essential that the store continued to trade so that the landlord could attractively market the remaining units in the shopping centre to other potential business tenants. Unfortunately, the supermarket was loss-making, so the defendant decided to close it. The claimant applied for an order for specific performance, claiming that damages for the defendant’s breach of the lease would not be an adequate remedy. The Court of Appeal granted the order for specific performance, but this was reversed unanimously by the House of Lords.

Lord Hoffman confirmed that it had been the usual practice of the courts not to grant an order for specific performance (or a mandatory injunction) compelling a party to continue to run their business because such an order would require the court’s constant supervision. This would take the form of the claimant often coming to the court seeking the court’s further punishment of the defendant for breaching the order of specific performance. The only weapon of punishment open to the court would be to treat the defendant as being guilty of contempt of court. This sanction by the court was not, perhaps, appropriate for a corporate defendant who would have to waste time and money in running their business (at a loss) simply to comply with a court order.

In addition, the loss that the defendant incurs in continuing to run the business may be far greater than the detriment the claimant would suffer through the defendant breaching his contract with the claimant. The aim of the law of contract was not to punish the defendant in his wrong-doing but to give the claimant adequate (but no more) compensation for his loss. Requiring the defendant to continue to run a loss-making business was punishing him whilst not essentially compensating the claimant.

Lord Hoffman held that an order for specific performance should not be granted if it required a defendant to continue an activity over a period of time. On the other hand, it could be granted where it required the defendant to achieve a one-off objective. Specific performance had been ordered, for example, in relation to a tenant’s repairing covenants in a lease34 because the court just had to satisfy itself that the work had been carried out.

Lord Hoffman described the remedy of specific35 Certain types of contract can be considered where specific performance will, and will not, usually be granted. They are contracts concerning:

[a] thesaleofland;

[b] the sale of chattels;

[c] the sale of shares; and

[d] employment obligations.

The sale of land

The breach of a contract for the sale of land36 will normally merit an order for specific perform-ance being granted for it. Such a contract is made in English law when both parties exchange their own part of the contract. After that point, the contract is prima facie specifically enforceable if one party should breach the contract by refusing to sell the land to the other.

The rationale behind this is that all land is seen as unique. No amount of damages can adequately compensate a claimant if the defendant refuses to sell the land to him for the claimant cannot go and buy another identical piece of land on the open market.