Emerging Economies’ IP and Industrial Policies

10

Emerging Economies’ IP and Industrial Policies

THIS CHAPTER RETRACES the past and present intellectual property policies relating to pharmaceutical industrial development of middle income developing countries, many of which are often referred to today as emerging economies. Although the original spirit of IP protection in encouraging creativity may not be as narrow as this, IP policies could be tools of industrial development if they are combined with coordinated efforts to promote scientific and technical skill and knowledge as well, to encourage innovative business management and market growth.

The development of the Japanese Patent Law and its role in increasing the competitiveness of R&D and their results in the pharmaceutical sector may offer a comparative example, as Japan’s economy, during several decades in the second half of the twentieth century, could be characterised as an emerging economy at that time.

I INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION AS INDUSTRIAL POLICY TOOLS

A Patent Protection of chemicals, pharmaceuticals and foods

The chemical industry grew during a period of fierce competition in the first three decades of the twentieth century. Until World War I, Germany’s chemical industry, which had grown fast since the turn of the century,1 was generally reckoned to be far ahead of all other countries and was regarded as ‘the Pharmacy of the World’. At that time, the US chemical industry was mainly of pharmaceutical origin.2 Chemical development in the US came later, with American leadership during and after World War II. In the UK, the British Key Industry Protection policy for the chemical industry in the years after 1917 is said to have helped the UK catch up with US and German chemical industries.

Some companies moved from the chemical industry to pharmaceuticals, which came to be organised as an industry in the 1930s.3 UK and Swiss companies attempted to catch up with the most advanced German and US pharmaceutical technologies by licensing or by inventing around internationally available new technologies, aided by relatively weak domestic patent protection regimes. By the 1940s, latecomers such as Italy, Japan and India had also acquired varying degrees of technical skills in organic chemistry. These countries watched closely the evolution of technologies of more advanced countries in this field and studied the patent laws of these countries, with a view to adjusting their own. Patent laws in technological latecomer countries with relatively high skill levels incorporated industrial policy dimensions in a mirror-image response to patent protection in more advanced countries. Some categories of inventions were excluded from patentability, particularly where, as today, such exceptions were easily justifiable and accepted due to the popular belief that patents always raise prices and prevent a general and sustained supply of goods.

Since the enactment of its Patent Act in 1790, the US has not restricted patentability to particular fields of technology, including chemical substances, medicines or foods and beverages. The UK had granted patent protection for chemical substances inventions, but from 1919 stopped doing so until 1949, when product patent protection was restored. Medicines and foods were patentable throughout, but there were special rules based on public interest in the Patents Act of 1949 until the enactment of the 1977 Patents Act (see chapter 2). Subsequently, the UK Patent Act was amended in 1999 in conformity with the TRIPS Agreement and EC case law.4

In France, the first Patent Law was adopted in 1791 and amended in 1844. This law recognised the patentability of chemical and food inventions, but not medicines. In 1941, the system of visa by the Ministry of Health granted a period of exclusivity of six years to medicines and, in 1959, patent protection of medicines was established also by a special law. In 1968, the latter was integrated in the Patent Law and the visa system came to control only safety and efficacy of medicines. In Germany, chemical, drug and food substances were not protected by patent until 1967. It was only in 1978 that Switzerland and Italy introduced product patent protection, and in Spain, Portugal and Norway, as late as 1992.

It was explained that the inadequate wartime supply of chemical products from Germany led to this decision, encouraging domestic production. It was also held widely in Japan, as in India later, that in France and Germany, product patent protection prevented research in the field.6 The reintroduction in Japan of product patents for chemicals, pharmaceuticals and foods was discussed from the 1950s, but the actual introduction of such protection was retarded, due to public and industrial opinion that argued in favour of ‘public interest’.

In 1958, at the fifth revision Conference of the Paris Convention in Lisbon, the BIRPI7 tabled a draft proposing that each Member recognise the patentability of chemical substances under certain conditions encouraging the working of these patents through licensing.8 At that time, there were 25 Members with laws that protected chemical substances, but Members such as France, Italy, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia objected.9 The Paris Convention was therefore not amended on this point, and the draft resolution proposed by Germany was adopted instead. The resolution urged that the Paris Union study the possibility of providing patent protection for new chemical products in national legislation, given that inventions must be protected to promote technological progress.10 Product patents are necessary to protect pharmaceutical inventions, because most process patents can be circumvented by those with technological skills in chemistry (and, later, in biotechnology).

In Japan, the appropriateness of introducing product patent protection was considered since the 1950s,11 in the light of the proposals made at the Lisbon Conference and in consideration of Japan’s domestic technological level, until product patent protection was finally introduced in 1976. In Japan, adopting the standards of the most developed countries was regarded as desirable, and patent protection was seen as beneficial for technological creativity. Most chemical industry representatives supported the introduction of product patent protection. They felt that too much R&D effort was spent on exploring different processes of producing chemical products patented abroad and on litigation, and that product patents would make R&D more effective. However, it took two decades for Japan’s pharmaceutical industry to gain confidence in its ability to compete with foreign companies.12

The Japanese Patent Law13 still retains some of the expressions of earlier days, when encouraging local invention was seen as a means of technological and industrial development and the industry looked to foreign examples for the optimum methods and levels of protection. The Japanese Patent Law is one of the few patent laws in the world to have explicitly defined invention; most patent laws have simply defined criteria by which to recognise inventions.14 Article 2, paragraph 1, of the Japanese Patent Law defines invention as ‘the highly advanced creation of technical ideas by which a law of nature is utilised’.

This definition was introduced in 1959 and was influenced by German academic writings of the nineteenth century, when the laws of nature were important for machines and heavy industry at that time.15 Based on this definition, certain types of ideas, such as in relation to methods of solving mathematical formulas, unfinished inventions and certain types of business models, have not been accepted as inventions, either because they were not considered to be technical ideas, or did not utilise a law of nature (chapter 12). This rigid statutory definition of invention has not prevented the advancement of biotechnology, but it may become obsolete in the future with further advancement of science and technology.

Another expression which is also a remnant of the past is Article 1 of the Japanese Patent Act, which states its objective to encourage inventions by promoting their protection and utilisation so as ‘to contribute to the development of industry’. Article 29(1) of the Japanese Patent Law stipulates that ‘any person who has made an invention which is industrially applicable may obtain a patent therefor’, excluding those inventions which were publicly known, worked or described,16 but leaves the explanation of ‘inventive step’ until Article 29(2). This is probably because the requirement of inventive step is inherent in the concept of invention. The reason why the patentability criterion of ‘industrial application’ is emphasised may be related to the stated objective of the law. Based on Article 1, inventions which can be used in pure science have not been patentable, because it is thought that the legal monopoly over such inventions could hinder industrial development. By the same token, therapeutic methods directly dealing with the human body for health reasons have not been considered as ‘industry’, and so not patentable, although the latter thinking is increasingly contested due to new biotechnology therapies working directly on human genes for treatment purposes. Diagnostic methods using extracted parts of the body, such as blood or urine, have already been patentable, because they are not considered as part of the human body. However, the fear that hospitals may become profit-maximising ‘companies’ animates still today the resistance of the Japanese medical profession to making therapeutic methods patentable. Article 32 of the Japanese Act is entitled ‘unpatentable inventions’ and stipulates that inventions liable to contravene public order, morality or public health shall not be patented, notwithstanding section 29. This provision, however, has never been used as a reason for the final rejection of a patent. Significantly, the Japanese Patent Law17 has maintained provisions relating to the conditions for compulsory licensing in three situations: on the grounds of non-working after four years have lapsed since the filing date of the application (Article 83), when a patented invention would utilise another person’s patented invention, registered utility model or registered design (Article 92), and when the working of a patented invention is particularly necessary for the public interest (Article 93). The Guidelines on Compulsory Licences, amended in 1997, provide that compulsory licences be issued in conformity with the TRIPS Agreement.18 In fact, these provisions have not been used either.

B Indian Patents Act 1970

In India, under British colonial rule, the first Act relating to patent rights was passed in 1856; it was replaced by the Indian Patents & Designs Act in 1911. After gaining independence in 1947, India’s government appointed B Tek Chand to lead the Patents Enquiry Committee (1948–50),19 and, subsequently, Justice Ayyangar to advise the government with a view to amending the Patents Act. The 400-page Ayyangar Report20 meticulously compared the patent systems of the world, their historical development and functioning in industrial development, particularly in the US, the UK, Germany and other European countries, Canada, the Soviet Union and East European countries. He studied the provisions of the Paris Convention and the Lisbon revisions discussions in particular. The Report also examined the recommendations of the Patents Enquiry Committee that led to the 1953 Indian Patents Act Bill, and criticised many of its recommendations.

The Ayyangar Report asserted that ‘patents are taken [by foreign companies in developing countries] not in the interests of the economy of the country granting the patent or with a view to manufacture there but with the main object of protecting an export market from competition from rival manufacturers particularly those in other parts of the world.’21 The Report argued that: ‘the conservation of foreign exchange is a matter of prime importance [for India] . . . that any increase in the price of the patented products imported into the country must to that extent be a disadvantage to the nation’s economy’.22 According to the Report, if the right holder was the monopoly supplier of a product whose patent was not worked in India, it would be possible that India would be deprived of alternative supplies of that product at cheaper prices.23

Justice Ayyangar argued that the patent system had been universally accepted for well over a century and would encourage Indian inventors in the future, although they took only a small share in the benefits of that system at that time.24 For this to happen, he argued, certain conditions must be fulfilled: (i) technical education and scientific diffusion and the number of persons reaching high proficiency by such education and science; (ii) massive production of industrial production which could absorb the products of the education and develop the instinct for research and direct it to useful and productive channels; (iii) patent procedures in India to assure working of foreign patents in India, opposition procedures, compulsory licensing, and government use of inventions including use by corporations owned and controlled by government; and (iv) special provisions for food and medicines.25

According to Justice Ayyangar, therefore, the scope of patentable inventions in India must be determined in light of India’s economic position and the degree of scientific and technological progress of the country. Interestingly, he distinguished two categories of non-patentable inventions: those inventions which were universally not patentable, and those inventions for which patents were not at that moment permitted under Indian law due to the state of its economy.26 The Ayyangar Report criticised the Patents Enquiry Commission’s recommendation that the term ‘invention’ should be given a wider meaning than in the past, asserting that having a wide scope of patentable inventions would be disadvantageous to India. According to Justice Ayyangar:

It does not need much argument to establish that, if the scope of patentable inventions were widened, the persons to benefit would be mostly inventors in the highly advanced industrial countries and for the use of these inventions which are not subject to patents in any country of the world other than in the United Kingdom, the industries in India would have to pay a tax in the shape of royalty.27

For the same reason, the Ayyangar Report also opposed the Tek Chand Committee recommendation that India should adhere to the Paris Convention for India’s economic interest (see chapter 2). This was in view particularly of developed countries’ tendencies to propose strengthening patent protection substantially; for example, the product patent protection of chemical inventions and the restriction on the use of compulsory licensing, as shown at the Lisbon revision conference.28

The Ayyangar Report opposed product patent protection,29 but urged that processes should be patentable for the following industrial reasons:

To render even the process unpatentable is I consider not in [the] public interest as the grant of exclusive rights to the process which an inventor has devised would accelerated [sic] research in developing other processes by offering an economic inducement to the discovery of alternative processes leading again to a larger volume of manufacture at competitive prices.30

The Indian Patents Act 1970, was inspired by the views and analyses of Judge Ayyangar, although the general framework of the UK Patents Act 1949 was largely retained.31 The Act reflects the thinking that the country’s patent law should be micromanaged to fit the strengths and weaknesses of its industry, and so the international norms should be flexible to allow such national interest. Underlying this Report was the message that the narrower the scope of patent protection, the fewer patents would be held by foreigners, and the opportunity for the development of Indian industry would increase. The Report also encouraged the thinking that India’s patent law should make it difficult to patent the types of technologies for which multinationals tend to apply for protection in India.

The Patents Act 1970, entered into force on 20 April 1972. It defined inventions, non-inventions and those inventions that are not patentable.

An ‘invention’ was defined in section 2(1)(j) of the Act as:

any new and useful:

(i) art, process, method or manner of manufacture;

(ii) machine, apparatus and other Article;

(iii) substance produced by manufacture, and any new and useful improvement of any of them.32

The Indian Patent Act 1970 enumerates the following list of ‘what are not inventions’ within the meaning of this Act in section 3, under Chapter II, entitled ‘Inventions not Patentable’:35

(a) invention which is frivolous or which claims anything obvious contrary to well established natural laws; (b) an invention the primary or intended use of which would be contrary to law or morality or injurious to public health; (c) the mere discovery of a scientific principle or the formulation of an abstract theory; (d) the mere discovery of any new property of new use for a known substance or of the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant; (e) a substance obtained by a mere admixture resulting only in the aggregation of the properties of the components thereof or a process for producing such substance; (f) the mere arrangement or re-arrangement or duplication of known devices each functioning independently of one another in a known way; (g) a method or process for testing applicable during the process of manufacture for rendering the machine, apparatus or other equipment more efficient or for the improvement or restoration of the existing machine, apparatus or other equipment or for the improvement or control of manufacture; (h) a method of agriculture or horticulture; (i) any process for the medicinal, surgical, curative, prophylactic or other treatment of human beings or any process for a similar treatment of animals or plants to render them free of disease or to increase their economic value or that of their products.

Some of the items designated in paragraphs (a), (b), (c) and (f), such as mathematical formulae, would be universally non-patentable. Part of the above list, (i) for example, is shared by other jurisdictions such as Japan and, later, the European Patent Convention (EPC). Others, by contrast, are not common in other patent laws. Some of these provisions seem original to India and may describe ‘inventions not patentable’ in India due to the development stage of India’s economy, as suggested by Justice Ayyangar. The list of those non-inventions and inventions that are not patentable by the criteria specific to India became longer and more complex as the Act went through amendments in 2002 and 2005.

However, trying to outline the comprehensiveness of what is not an invention in brief, abstract sentences is difficult to begin with. Furthermore, the word ‘mere’, which appears frequently in section 3, creates a vast field of negation and blurs the scope of what is not negated. There is no country that recognises as an invention a mere principle or abstract theory, or that recognises as novel the mere discovery of a new property or a mere admixture of a known substance. In practice, much would depend on the practices of the IPO, clear examination guidelines and court decisions.

On the other hand, the non-patentability of medicines, foods or substances produced by chemical processes was very clear. Section 5 of the Indian Patents Act 1970, entitled ‘Inventions where only methods or processes of manufacture Patentable’, excluded from patentability inventions (a) claiming substances intended for use, or capable of being used, as food or medicines; or (b) relating to substances prepared or produced by chemical processes including alloys, optical glass, semi-conductors and inter-metallic compounds; only patent protection on methods or manufacturing processes was provided to inventions (section 5(1)). As Justice Ayyangar had recommended, only process patent protection was provided for food and medicines, for five years from the date of sealing of the patent, or seven years from the date of the patent, whichever period should be shorter (section 53(1)(a)), in comparison to the patent term of 14 years from the date of the patent (section 53(1)(b)) granted to other inventions.

Furthermore, there was a system of ‘licences of right’ (see chapter 2) under which the Controller of Patents automatically ‘endorsed’ medicines, foods and chemical processes from the commencement of the Patents Act 1970, or from the expiration of three years from the date of sealing of the patent under the Indian Patents and Designs Act 1911, whichever is later,36 so that any person could work the patent without the authorisation of the patent owner. Finally, the compulsory licensing provisions of the Act are broadly worded (see chapter 9) to make such licensing readily available for a wide range of grounds, including non-working of the patent in India, as well as other grounds such as public interest, unreasonable prices or insufficient supplies in both domestic and export markets.37

According to Ganesan (see chapter 4):

The cumulative effect of all these provisions is that the Indian Patents Act, 1970 virtually provides no patent protection in food, pharmaceutical and chemical sectors. It must be remembered that it takes anywhere between seven to ten years for a drug to be brought into the commercial market from the date of the patent application, whereas the term of the patent-and that too a process patent-is only seven years under the Indian law. No company is, therefore, interested in taking out a patent in India. The ‘licence of right’ and ‘compulsory licensing’ provisions of the Indian law are indeed and ‘over kill’of the subject matter; there has been no need to use them since the coming into force of the Patents Act in April, 1972.38

In fact, the Controller of Patents issued compulsory licences on only four occasions following the enactment of the Patents Act in 1970.39

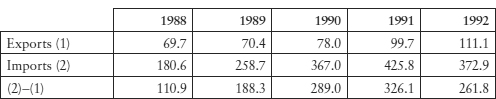

Following the entry into force of the Patents Act 1970, the policy was successful in reducing foreign patents to insignificant numbers, as Table 10.1 shows.40

Table 10.1: Applications for patents, Indian and foreign, before and after the Patents Act 1970

The legitimacy of patent protection was difficult for different segments of the Indian society to agree upon, because it depended, among other things, on how multinational companies behaved.41 Furthermore, the acceptability of patent protection seems to have depended on the prices of goods, as well as on the opportunities that it offered to domestic industry, as the Ayyangar Report predicted. How could these concerns be reconciled with the limited goal of patent protection, which is to encourage long-term scientific and technological endeavours not guaranteed to bear fruit? If the perspective is thus set, the weight of public interest is much greater than that of investing in and promoting scientific and technological endeavours to make IP protection meaningful. It seems that the initial policy choice and way of looking at things influenced the future course of events.

II PRE-TRIPS IMPORT SUBSTITUTION POLICIES FOR PHARMACEUTICALS

A India’s Success in Building a Pharmaceutical Industry

According to Redwood, ‘the Patents Act, 1970, was the instrument that made it possible for the Indian-owned industry to expand rapidly, because the Act legalised “copying” of drugs that are patentable as products throughout the industrialised world but unprotectable in India.’42 Later in 2009, a commentary was made in the context of the EU India FTA negotiations that the absence of IP protection was what had promoted the Indian pharmaceutical industry:

the strengthening of IPR protection sought by the EU may contribute to limit rather than to foster Indian industrial and technological development which – like developed countries earlier – substantially relies on a flexible IPRs regime. A good illustration is the strong development before the introduction of pharmaceutical product patents in 2005 of the Indian pharmaceutical industry, which has become a major world supplier of pharmaceutical active ingredients and medicines.43

However, a weak IP protection policy alone could not have led to India’s successful development of a domestic pharmaceutical industry. There seem to have been multiple factors that made it possible for India to achieve the economies of scale; skills in organic chemistry and the ability to cheaply manufacture expensive products patented in the US and Europe, which gave price advantages to India’s products, were key. This was made possible particularly by a well-coordinated national scientific leadership in disseminating technologies to private companies, creating an educational infrastructure that enabled in-house know-how to flourish.44

According to Chaudhuri, national chemical or pharmaceutical laboratories such as the National Chemical Laboratory (NCL), Central Drug Research Institute (CDRI) and Indian Institute of Chemical Technology (IICT) conducted research on manufacturing technologies under the leadership of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). Many Indian companies, such as Cipla, Ranbaxy, Lupin, Nicholas Piramal and Wockhardt, benefited from the activities of these laboratories.45 Cipla (see chapter 9), for example, collaborated with NCL and IICT in particular and successfully launched products like vin-blastine sulphate and vincristine sulphate (anti-cancer drugs), salbutamol (anti-asthma drug), zidovudine (AZT, see chapter 8). The process for manufacturing zidovudine was developed by IICT after the organisation was approached by the Indian Council of Medical Research.

During the last 30 years, the CSIR has filed 25 per cent of all the process patent applications in India. Funding for the CSIR’s research came primarily from government funds, but there was also considerable investment by industry. As a technical expert and businessman, Chairman Hamied of Cipla also played an important role in the development of India’s pharmaceutical industry. The policy of linking knowledge and family capital abroad to Indian educational institutions and then to actual manufacturing allowed the creation of in-house know-how in the 1980s.46 This factor, as well as India’s export markets in the then Soviet Union47 and Central and Eastern Europe allowed some economies of scale, although the significant increase in Indian export of pharmaceuticals only started in the late 1990s. Another factor in India’s success was the collaboration between business and the national laboratory started by a group of business-minded scientists, government officials and industrialists.48

Other policy instruments included foreign exchange and business regulations, restrictions on the import of finished formulations, high tariffs, local content requirements and ownership control by company law. In the pharmaceutical field specifically, they have allowed 13 multinationals to produce only certain active pharmaceutical ingredients that have high technological standards and formulation processes.49

When the 1970 Patent Act was introduced, Indian companies held a total market share of around 32 per cent in India, but by 1998, this figure increased to 68 per cent.51 The entry barrier to the Indian pharmaceutical market is not high and the market is competitive. Wockhardt is an example of a small-scale company that grew to be one of India’s top companies.

Table 10.2: Market Shares of Foreign Companies and Indian Companies in India’s Pharmaceutical Industry (%)

Year 1952 1970 1978 1980 1991 1998 2004 | Foreign Companies 38 68 60 50 40 32 23 | Indian Companies 62 32 40 50 60 68 77 |

Source: S Chaudhuri,The WTO and India’s Pharmaceuticals Industry, (Oxford University Press, 2005) 18.

B Brazil’s Import Substitution Policies

Import substitution policies associated with lax IP protection of the 1970s led to varying economic results in different countries, especially developing countries such as India, Thailand, Bangladesh and countries in Latin America. In Latin America, governments promoted import substitution industrialisation (ISI) policies in technology-intensive industries, particularly for pharmaceuticals, through the restriction of IPRs and state-owned and managed economic enterprises in the post-World War II era. In these countries, patent protection of chemical substances and, in Brazil, even process patents for manufacturing pharmaceuticals, were abolished.52

Brazil was one of the 11 original Paris Convention Members (1884) and had a long tradition53 of offering patent protection. However, in 1945, the country’s legislation was modified to exclude from patentability inventions relating to foodstuffs, medicines, materials and substances obtained by chemical means or processes. In 1969, process patent protection for pharmaceuticals was also eliminated entirely from the Brazilian Industrial Property Code, with a view to domestically producing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and intermediary products.

To encourage national production, the Brazilian government implemented a policy of centralised purchasing to promote local production of medicines. Import taxes on medicines were levied at prohibitive levels whilst at the same time the intermediary inputs for local production were taxed mildly and local production was subsidised.54 To develop the skills necessary for domestic production, Companhia de Desenvolvimento Tecnologico was established to coordinate R&D, and state-run companies such as Nordeste Quimica SA and Norquisa became active in production.

The abolition of pharmaceutical patent protection was intended to protect domestic companies from powerful multinational corporations, with the expectation that the former would invest in local manufacturing of the most promising active chemical substances. However, in 1980 and 1994, domestic companies held 28 per cent and 30 per cent, respectively, of the market share in Brazil and multinationals 70 per cent and 72 per cent. The share of domestic companies increased by only 2 per cent.55

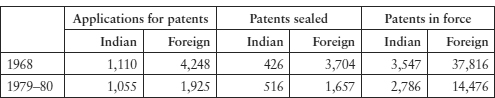

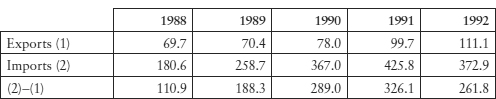

Table 10.3: Brazil’s Trade in Medicinal and Pharmaceutical Products, in 100 million US$

Source: United Nations Trade Statistics Yearbook 1992, as cited in Redwood, Brazil: The Future Impact of Pharmaceutical Patents (n 50) 5.

The elimination of patent protection did not cause domestic industry to flourish, due partly to fierce competition in the world market of APIs and intermediaries (Table 10.3). Teaching focused on theory was successful at Brazilian universities, but the skills and know-how necessary in chemical synthesis for producing ingredients and intermediaries with sufficient purity were not accumulated. Government subsidies dissipated and, by 1990, 1,700 chemical pharmaceutical factories had shut down.56 Today, Brazil imports most of its active pharmaceutical ingredients from India and China.

Brazil’s economy has depended heavily on its exports to the US; a situation which US multinationals generally used as leverage for negotiations. The United States Trade Representative (USTR) pressured such countries as Argentina, Brazil, India, Singapore, Turkey and Mexico under section 301 of the US Trade Act (see chapter 3) from the end of the 1980s. In 1993, Brazil was placed on the priority watch list (but in 1995, demoted to the watch list).

C China’s IP Policy before WTO Accession

China’s policy contrasts with the policies of countries that weakened patent protection for the development of their domestic pharmaceutical industries. In China, the initial stages of intellectual property protection began during the 1980s along with the introduction of a policy of opening the country to foreign business. In this decade, the Trademark Law (1982),57 the Patent Law (1984)58 and the Copyright Law (1990) were all enacted. Subsequently, relevant laws and regulations were revised in the 1990s, in preparation for prospective membership of the WTO. By the First Patent Amendment Act, which entered into force in January 1993, product patents, as well as use and formulation patents, were introduced. China became a WTO member on 11 December 2001.

According to Ganea and Haijun, China’s IP laws resulted from ‘commitments made in order to become an accepted member of the world trade community rather than from recognition that IP laws would foster innovation and economic development in the domestic context’.59 China realised that, without IP protection, desired technology-intensive and IP sensitive investment would stay away. It was probably for these reasons that China agreed to grant administrative protection of a maximum of seven and a half years for pharmaceutical inventions patented in the US, European Community Member countries and Japan.

Whatever Chinese companies or researchers think about IPR protection, however, the Chinese Government seems to consider that becoming a ‘leader in technology’ cannot be achieved without respecting intellectual property rights. Confidence in patent protection is popularly justified by the oft-quoted story of the four ancient great inventions of China60 which are the compass, gunpowder, papermaking and printing which, it is humourously maintained, could have yielded great income to China had they been patented.

The Chinese Patent Law was adopted on 12 March 1984 and was revised three times: on 4 September 1992, 25 August 2000 and 29 December 2008. China introduced product patent protection in the second amendment, in Article 11.

China’s overall policy of encouraging foreign direct investment (FDI) as part of its efforts to raise the technological levels of domestic companies avoided direct confrontation of domestic and foreign companies over IPRs, as reflected in some of its court cases (see chapter 9 and below p 385). The Chinese Government has used various means, including subsidising filing fees, to encourage domestic companies to file patents. The result has been a rapid increase in the number of domestic filings by Chinese residents. Foreign patenting by Chinese entities initially lagged far behind domestic ones, probably for technological reasons, but, in absolute number, increased rapidly. Another possible reason for the relatively low level of Chinese patenting abroad was the obligation introduced by the second amendment of the Patent Law in 1992 for Chinese applicants to file first in China. This system was modified by the third amendment of the Patent Law, as shown later in this chapter. China became the fifth largest PCT user in 2009, with a strong growth rate of 29.7 per cent, representing some 7,946 international applications.61

III TRIPS AGREEMENT AND EMERGING ECONOMIES

The TRIPS Agreement took a radical step in comparison to the Paris Convention, in making it obligatory to protect not only processes, but also ‘products’, with the provisions of transition periods of 10 years for developing countries and until 2010 for LDCs (extended until 31 December 2015 – see chapters 5 and 9). It is generally in the emerging economies that patents tend to become controversial. First of all, foreign direct investment increases where the market size is important. These markets are generally those countries with a large population with a rising income, albeit of limited classes, and with the capacity to imitate and technological skills to produce, creating conflicts over intellectual property. Secondly, there are rising expectations for better healthcare in these countries not only among high income classes but particularly among a large segment of poor people.

A India’s TRIPS Implementation

i TRIPS Challenge

Certain technological sectors of India will want reasonable protection for IPR (to build their own inventive industries) and may also be willing to make concessions in that direction in order to gain other major trade advantages with developed country markets, generally. India accepted the TRIPS Agreement in a single undertaking in 1994 based mainly on a desire to preserve within the framework of the WTO the principle of most-favoured nation treatment and access to other world markets.

In 1994, Ganesan explained the implications of the TRIPS Agreement for India. He asserted that India’s copyright law was ahead of the provisions of the TRIPS agreement62 in the matters of software and protection against piracy of cinematographic works; he said that protection of trademarks, trade secrets and industrial designs were on a par with generally accepted international standards.63

In the area of patents, however, he warned that:

there is no meeting ground between the provisions of the Indian Patents Act, 1970 and the norms and standards for protection incorporated in the TRIPS agreement . . . the TRIPS agreement requires product patents to be given in all fields of technology without exception; the duration of the patent to be at least 20 years uniformly; compulsory licence to be given on the individual merits of a case but only after approaching the patent owner for obtaining a licence on reasonable commercial terms and conditions; the burden of proof in the case of process patents (that lead directly to new products) to be placed on the defendant in the circumstances prescribed; patent rights being available equally regardless of whether the products are locally produced or imported; and so on.64

Ganesan then turned to the major concern at the time: that the implementation of the TRIPS Agreement might result in soaring medicine prices. He pointed out that it would be important to distinguish the price of drugs that were patented from those that were not, and suggested that:

it is unlikely that drugs covered by patents will exceed 10 to 15% by value of the total drug market in our country at any time in the foreseeable future. There is no reason why the prices of drugs not covered by patents should rise so steeply because of the patent system.65

India, as a developing country Member of the WTO, was under an obligation to bring its laws and regulations into line with the TRIPS Agreement by 1 January 2000 (Article 65.2), institute the mailbox application system (Article 70.8) and grant exclusive marketing rights as from the entry into force of the WTO Agreement, if it does not introduce patent protection of agricultural and chemical products (Article 70.9). It was further required to introduce product patent protection (Article 65.4) by 1 January 2005 (see chapter 5).

Subsequent to the adoption of the TRIPS Agreement, the Indian Patents Act 1970 was amended in 1999, 2002 and 2005. The mailbox application mechanism and the mechanism for granting exclusive marketing rights (EMRs) were introduced by the Patents (Amendment) Act 1999, after a WTO dispute on this question, India–Patents66. Then, by the Patents (Amendment) Act 2002, which came into effect on 20 May 2003, the 20-year patent term, reversal of the burden of proof for process patent infringements, and changes in the conditions for compulsory licensing were introduced. Last, the Patents (Amendment) Act 2005, adopted on 5 April 2005, put agricultural-chemical and pharmaceutical product patent protection into full effect retroactively as of 1 January 2005, after the full use of the 10-year transition period provided for by Article 65.4 of the TRIPS Agreement (see chapter 5).

The amendments in 2002 included provisions concerning the term of patent protection to conform to Article 33 of the TRIPS Agreement, and Section 53 provided a term of 20 years after the date of filing of the application for the patent.67 India acceded to the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (Paris Convention) and the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) which entered into force for India in December 1998. The amendments of 2002 also reflected these changes. Provisions concerning compulsory licensing were also modified.

The amendment in 2002 of India’s Patents Act 1970 left to a later day the implementation of the product patent protection, which developing countries including India were required to introduce by 1 January 2005.

Concerns were expressed that India’s generic industry would lose its competitiveness, if product patent protection were introduced. Scherer warned that India, like Italy in the past, was in danger of losing its first-mover advantage of supplying medicine at 50–65 per cent of the original price before the entry of generic companies in developed countries, who normally wait for the patent expiry of the medicines they manufacture. India, without product patent protection, had the advantage of freely copying those new medicines patented abroad. The timing of their market entry gave them advantages over other generic companies, because they were able to put their medicines on the market before the price went down due to the entry of many generic companies.68 Indian companies also had the marketing skills and knowledge to export products that were patented abroad and expensive in large markets to markets where there were no patent restrictions. India’s generic manufacturers were becoming increasingly competitive and global. The patents for the top 10 pharmaceuticals (such as Lipitor (atorvastatin, a cholesterol-lowering medication), Zyprexa (olanzapin, for schizophrenia treatment), and Neutrogin (lenograstim, for treatment of anemia) were expiring around 2010. According to Scherer, the Patents (Amendment) Act 2005, therefore, should introduce quid pro quo provisions necessary to counter the negative effects of the TRIPS Agreement on domestic industries.69

Concerns had been expressed also over the possible social consequences of India’s reintroduction of product patents. Civil society groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières, considering India as ‘the number one source of affordable medicines’,70 warned against India introducing product patent protection:71

Sick people in India and around the world depend on the willingness of Indian producers to carry out the research to develop and manufacture affordable generic versions of second-line AIDS drugs and other new medicines. India has a long history of fighting for protection of public health over intellectual property: it led developing countries’ resistance to the TRIPS Agreement during the Uruguay Round of WTO negotiations, and also played a key role during the 2001 WTO ministerial conference in Doha, which resulted in the adoption of the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health. Unlike other developing countries, it has also waited as long as was permitted by TRIPS before introducing patents on pharmaceutical products. In the new post-2005 TRIPS context, it is crucial that India continue to develop policies that promote access to medicines, not just out of responsibility to its own people, but as a lifeline to patients in other developing countries.72

However, in the specific historical context of that time, there was high hope in India that the country was becoming an innovative developing country. In December 2004, when the Ordinance73 amending the Indian Patents Act 1970 was adopted by the Indian Parliament, K Nath, Minister of Commerce & Industry, assured the public, stating that India’s larger pharmaceutical industry was becoming more innovative than in the past, spending much more on R&D than in the past and, therefore, the concerns and fears expressed by various sections were wholly misplaced.74

Amidst considerable political opposition, Indian biotechnology companies joined forces with the CSIR75 which started calling for the introduction of product patents as part of a strategy to make India an ‘innovative’ developing country. In 2004, the sales volume of India’s biotechnology companies was up 36.5 per cent from the previous year, to a total of US$1.07 billion.76