Elements of good style: clarity, consistency, effectiveness

7 Elements of good style: clarity, consistency, effectiveness

7.1 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Style in legal writing is to some extent a matter of personal preference or company policy. The only unbreakable rules of style in legal documents and letters are that your writing should be as easy to understand as possible and that it should avoid offensive terms.

In addition to drafting letters, emails and other communications, most lawyers also spend a considerable amount of time creating legal documents for a variety of purposes. These may either be intended for use in court proceedings or for use in non-contentious business such as sales of land, goods or services.

Typical documents prepared by lawyers for use in court include statements of claim, witness statements, divorce petitions, petitions for bankruptcy and affidavits.

Typical documents prepared by lawyers for non-contentious purposes include transfers of land, contracts for sale of goods, articles of association for companies, licences and options.

The style of writing used in legal documents differs from the style used in legal correspondence. This is because the purpose of legal documents is different from that of legal correspondence.

Most legal documents used in court proceedings either act as evidence in support or defence of some claim or make allegations and arguments either in support or in defence of a claim. Most legal documents used in non-contentious business generally record an agreement between parties. Such documents are intended primarily to regulate all aspects of the agreement reached between the parties. They lay down the obligations each party must carry out and specify the consequences of failure. They are intended to be legally effective in court. Consequently, the language used in legal documents displays certain typical features which often make them difficult to read. These include:

• Use of terms of art. These are words which have a precise and defined legal meaning. They may not be familiar to the layperson, but cannot be replaced by other words.

• Use of defined terms. Many legal documents contain a definitions section in which the parties agree that certain words used repetitively throughout the document shall have an agreed meaning.

• Repeated use of the words shall and must to express obligations, and may to express discretions (where the parties are entitled to do something but are not obliged to do it), as well as a number of other words and phrases of similar meaning.

These issues are dealt with in more detail in .

The writing used in legal correspondence usually has a different purpose. It is generally intended to provide information and advice, to put forward proposals, and to provide instructions to third parties.

However, all legal writing should aim at achieving three goals – clarity, consistency and effectiveness. The notes set out below show how these goals can be achieved in practice.

7.2 CLARITY

Writing of all kinds should be as easy to understand as possible. The key elements of clarity are:

• Clear thinking. Clarity of writing usually follows clarity of thought.

• Saying what you want to say as simply as possible.

• Saying it in such a way that the people you are writing for will understand it – consider the needs of the reader.

• Keep it as short as possible.

7.2.1 Planning

Start by considering the overall purpose of your document or letter. Before starting to draft a document you need to be sure that you have a clear idea of what the document is supposed to achieve and whether there are any problems that need to be overcome to allow it to be achieved. Ask yourself the following questions:

• Have you taken your client’s full instructions?

• Do you have all the relevant background information?

• What is your client’s main goal or concern?

• What are the main facts which provide the backbone of the document?

• What is the applicable law and how does it affect the drafting?

• Are there any good alternatives for the client? Would it be more effective or cheaper to approach the client’s goal in a different way? For example, if it seems that drafting the necessary documentation in English will be too difficult, consider the following options:

○ draft the document in your native language and have it translated and verified;

○ engage the services of a native English-speaking lawyer as a consultant in respect of the case;

○ draft the document as best as you can in English and have a legally-qualified English native speaker check and correct the documents.

• Are there any useful precedents (generic legal documents on which specific legal documents can be based) which could be used for the draft?

More detailed notes on drafting documents are contained in Chapter 11.

More detailed notes on correspondence are contained in Chapter 12.

7.2.2 Words

Whether writing documents or correspondence, the following guidelines are relevant.

7.2.2.1 Use the words that convey your meaning

Use the words that convey your meaning, and nothing more. Never use words simply because they look impressive and you want to try them out, or because you like the sound of them. There is a tendency in legal writing to use unnecessarily obscure words rather than their ordinary equivalents, perhaps out of a feeling that the obscure words are somehow more impressive.

7.2.2.2 Use ordinary English words where possible

Do not use a foreign phrase or jargon if you can think of an ordinary English word that means the same thing. For example, do not write modus operandi when you can write method, nor de rigeur when you can write obligatory.

In legal English, this is more difficult to achieve in practice than it is in ordinary English, because much of the terminology used (inter alia, ab initio, force majeure, mutatis mutandis) comes from French and Latin. These often act as shorthand for a longer English phrase. For example, inter alia comes out in English as ‘including but not limited to’. Your choice of vocabulary – between English or French and Latin – will be influenced by who you are writing to.

7.2.2.3 Avoid negative structures

Avoid negative structures where possible. There is a tendency in much business and legal writing to try to soften the impact of what is being said by using not un– (or not im-, il-, in-, etc) formations such as:

• not unreasonable

• not impossible

• not unjustifiable

• not unthinkable

• not negligible

Such structures make what you are saying less clear and definite. They become very hard to follow when more than one is used within a single sentence, e.g.:

It is not impossible that this matter will have a not inconsiderable bearing upon our decision.

Which, translated into ordinary English, reads:

It is possible that this matter will have a considerable bearing upon our decision.

7.2.3 Sentences

In addition to the notes on sentence structure set out in Chapter 4 above, bear in mind the following points.

7.2.3.1 Keep sentences short where possible

Use words economically to form your sentences. This does not necessarily mean that every sentence should be short (which might create a displeasing staccato effect) but that all unnecessary words should be removed: this will make your writing much more vigorous.

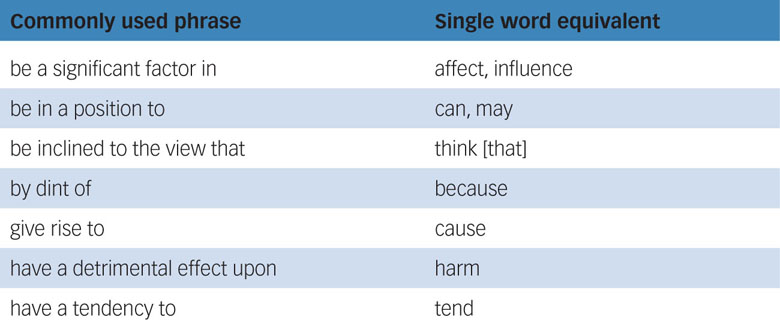

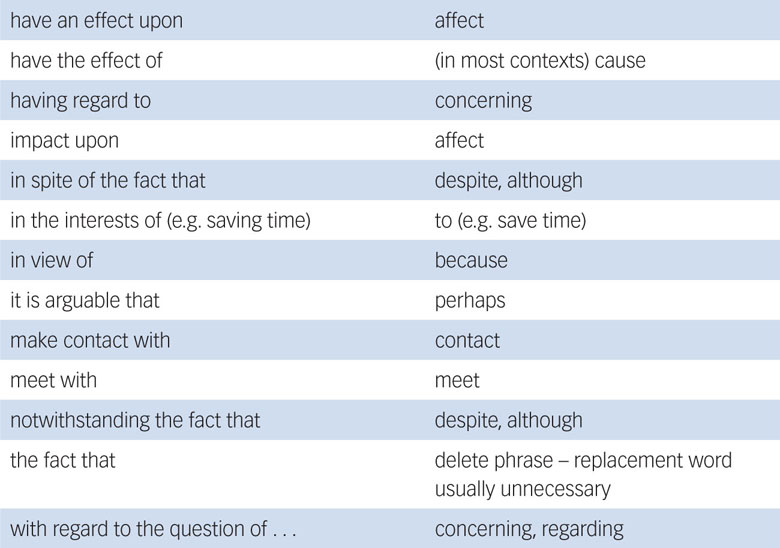

In particular, pay attention to phrases that introduce new pieces of information or argument. These can often be reduced to single words. Here are some examples:

7.2.3.2 Take care with the use of which

Which is a useful word, but is frequently used unnecessarily, usually involving further unnecessary verbiage. For example, the sentence:

These situations are governed by agreements which are made between different entities.

may be reduced to:

These situations are governed by agreements between different entities.

7.2.3.3 Use pronouns where possible

The use of pronouns avoids repetition of nouns, which is useful particularly where lengthy noun phrases (such as the names of documents or laws) are involved. For instance, try to avoid writing sentences like this:

The 2010 Terms and Conditions for the Provision of Services within the Metalwork and Woodwork Sectors are now in force. The 2010 Terms and Conditions for the Provision of Services within the Metalwork and Woodwork Sectors replace the large number of different agreements previously used.

Write instead:

The 2010 Terms and Conditions for the Provision of Services within the Metalwork and Woodwork Sectors are now in force. They replace the large number of different agreements previously used.

The 2010 Terms and Conditions for the Provision of Services within the Metalwork and Woodwork Sectors are now in force, and replace the large number of different agreements previously used.

However, as discussed in Chapter 8, one of the most common reasons for ambiguity in a text is where a sentence contains two or more nouns together with one pronoun in such a way that it becomes unclear which noun the pronoun is intended to replace. So only use a pronoun when it is crystal clear to what it relates.

7.2.3.4 One main idea per sentence

Try to have only one main idea per sentence. Where you want to add more than one piece of additional information about a subject introduced in a sentence, consider starting a new sentence. Always start with the most important piece of information, then deal with lesser matters, qualifications or exceptions.

For example, the sentence:

Unless the order is for the goods described in appendix 3, X shall deliver the goods to Y within 7 days.

would be better written as follows:

X shall deliver the goods to Y within 7 days of an order being received, unless the order is for the goods described in appendix 3.

And this sentence:

The company, the headquarters of which are in Oxford, specialises in pharmaceutical products and made a record profit last year.

would be better split up as follows:

The company specialises in pharmaceutical products. Its headquarters are in Oxford, and it made a record profit last year.

7.2.3.5 Use the active voice where possible

Voice refers to the relationship between a clause’s subject and its verb. The phrase, ‘the lawyer considered the documents’ is active because the verb ‘considered’ performs the action of the subject. The phrase, ‘the documents were considered by the lawyer’ is passive because the verb is acted upon.

The passive voice has the effect of deadening the impact of the action by burying it in the subsidiary part of the sentence. The active form highlights the action in the first part of the sentence.

However, overuse of the passive can lead to lack of clarity. The example given above leaves it unclear as to who is going to call the meeting. It also leads to less effective and less forceful communication with the reader.

Sentences using the active voice are shorter and more direct. In most cases the active voice is preferable. However, there may be cases in which the writer’s intention is to divert attention from the real subject. For example, ‘the contract was signed’ (passive), as opposed to, ‘I signed the contract’ (active).

Alternatively, the writer may use the passive voice to focus attention on the object in a case where that is more important than the subject. For example, ‘the meeting will be held’ (passive) as opposed to ‘the company will hold a meeting’ (active).

In these last two cases the passive should be used. In other cases it should be avoided.

7.2.3.6 Use positive phrases where possible

A positive phrase is usually better than a negative one. For example, ‘Clause 2 shall apply only if …’ is clearer than ‘Clause 2 shall not apply unless …’.

However, restrictions are often difficult to express in the positive rather than the negative without either:

• changing the meaning (‘A shall not sell goods except those made by B’ is a restriction whereas ‘A shall sell goods made by B’ is a positive obligation and therefore fundamentally different); or

• using indirect language (‘A may build anything except a house’ is less direct than saying ‘A may not build a house’).

In these cases, therefore, the negative forms should be used. In other cases they should be avoided.

7.2.4 Paragraphs

Paragraphs should not be defined by length. They are best treated as units of thought. In other words, each paragraph should deal with a single thought or topic. Change paragraphs when shifting to a new thought or topic.

Paragraphs should start with the main idea, and then deal with subordinate matters. The writing should move logically from one idea to the next. It should not dance about randomly between different ideas.