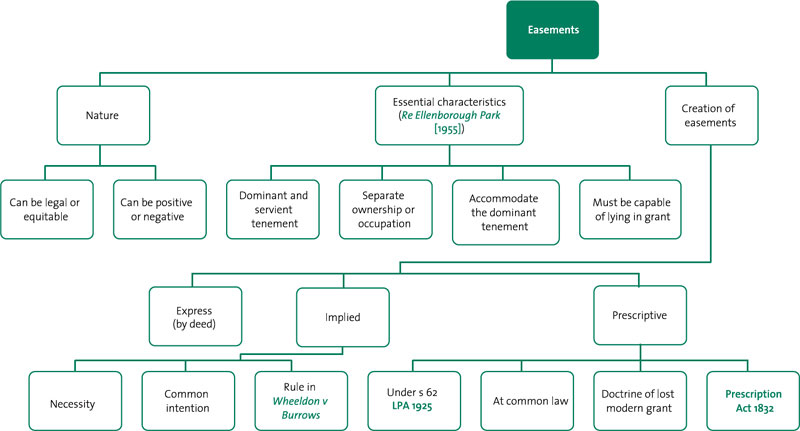

Easements

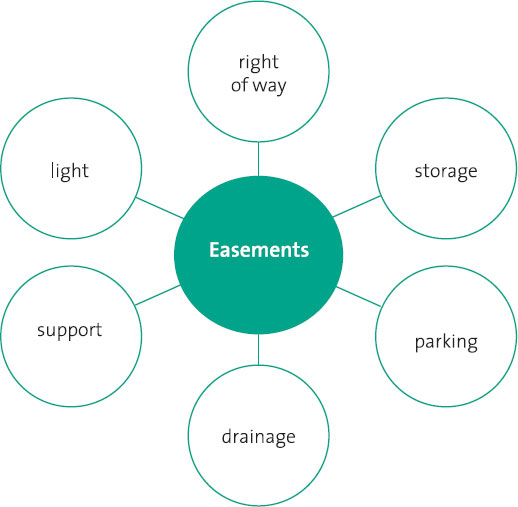

An easement is a right to use someone else’s land. The most common type of easement is a right of way over someone else’s property. However, there are also many other kinds of easement, including:

a right of storage;

a right of storage;

a right to park a car;

a right to park a car;

a right of drainage;

a right of drainage;

a right to support; and

a right to support; and

a right to light.

a right to light.

Understanding: the nature of easements

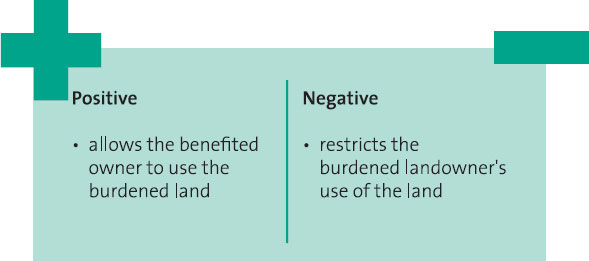

1. Easements can be legal or equitable, positive or negative in nature

A positive easement allows the benefited landowner to use the burdened land in some way; a negative easement gives the benefited landowner a right that prevents the burdened landowner from using their own land in a particular way.

Because of the restrictive nature of negative easements, examples of them are few and far between. The two main types of negative easement are a right to light and an easement of support.

The courts will not allow the creation of any new types of negative easement (Phipps v Pears [1964]).

No new negative easements

The ability of the courts to create new categories of positive easement, however, is not closed. New easements can thus be created so long as they are similar in nature to, or can be said to be a development of, others already established by case law (Dyce v Lady James Hay (1852) 1 Macq 305).

Common Pitfalls

Negative easements are often confused with freehold covenants; however, the two concepts are quite different. Whereas an easement is a right to do something on someone else’s land, a covenant constitutes either the right to prevent someone else from doing something on their own land, or the right to force someone to do something on their own land (for example, to maintain it). Covenants can also be far wider in their scope and more flexible than easements.

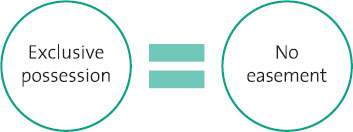

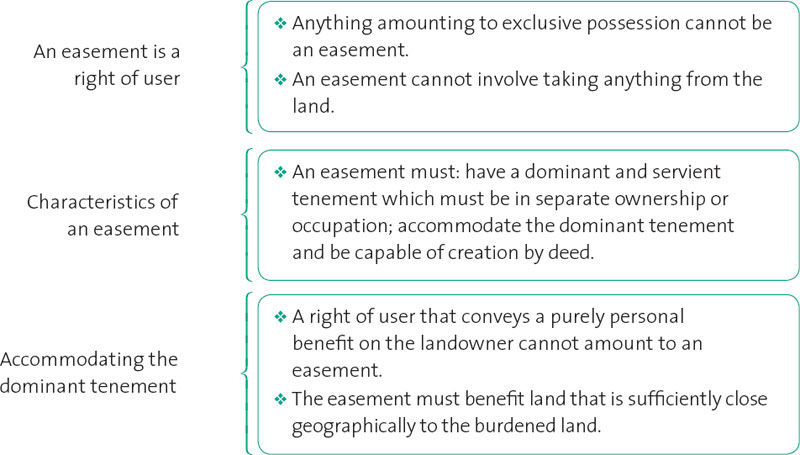

2. An easement is not a right to take anything from the land; nor does it confer a right of possession

Any right that amounts to exclusive possession of the burdened property cannot be an easement.

Consequently rights of storage are thus often difficult to establish.

Facts: The defendant had used a strip of land belonging to the claimant for 50 years, for the purpose of storing vehicles which were either being repaired or awaiting repair. Held: His claim to an easement over the land failed. His use of the land was too extensive to constitute an easement as it had, in effect, deprived the landowner from using his own land entirely.

Principle: Any right that amounts to exclusive possession of the burdened property cannot be an easement.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the difficulty in establishing easements of storage.

Case precedent – Grigsby v Melville [1972] 1 WLR 1355

Facts: The case concerned a claim to use a cellar room underneath the floor of an adjoining property. Access to the cellar was via some stairs, which led down from the benefiting owner’s house. The burdened landowner had no access to the space. Held: There was no easement. The benefiting landowner’s use of the land was such that it amounted to an exclusive right of user over the whole of the cellar.

Principle: Any right that amounts to exclusive possession of the burdened property cannot be an easement.

Application: Compare the facts of your scenario with this case to illustrate the difficulty in establishing easements of storage.

Aim Higher

Why are the easements in some cases granted and not in others? Matter of degree: if the landowner is prevented from using their land altogether, an easement will not be granted.

In particular, the right to park is problematic as a form of easement.

Facts: A right to park a car was held to constitute an easement, provided that the vehicles were not constantly in the same spaces and that they did not interfere with the burdened landowner’s reasonable use of the land. If the right had extended to the right to park a car exclusively in the same space 24 hours a day, this would not have been an easement, because it would have had the effect of depriving the landowner from using their land altogether.

Principle: If a right deprives the owner of the burdened property of the use of their property altogether, it cannot be an easement.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the difficulty in establishing easements of car parking.

Case precedent – Batchelor v Marlow (2003) 1 WLR 764

Facts: A claim to an easement of the right to park up to six cars on a plot of land between the hours of 9.30 am and 6.00 pm, Monday to Friday, failed on the basis that the claim was too intrusive on the burdened landowner.

Principle: Any right that deprives the owner of the burdened property of the reasonable use of their property cannot be an easement.

Application: Compare this case with the facts in your own problem question scenario to support your argument that an easement cannot be created.

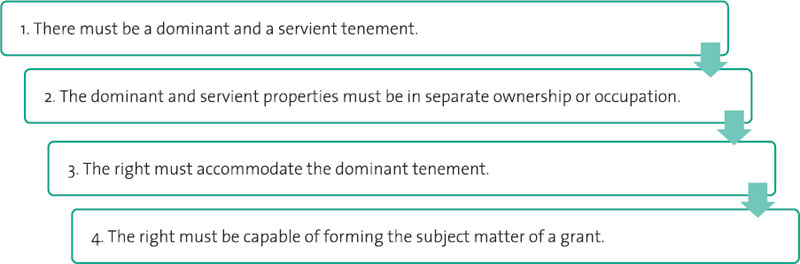

Essential characteristics of an easement

In order for a right to be capable of being an easement:

(Re Ellenborough Park [1955] 3 WLR 892)

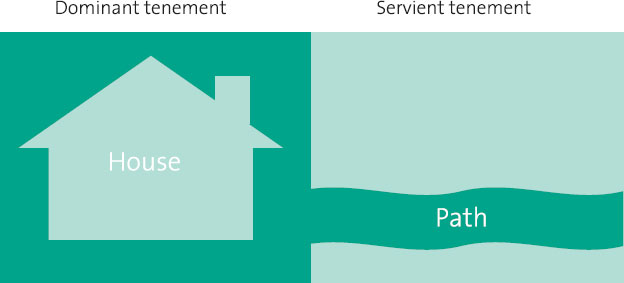

1. Dominant and servient tenement

The dominant tenement is the land with the benefit of the easement, and the burdened tenement is the land that is burdened by it. Thus, with a right of way, the servient tenement would be the land with the path running across it and the dominant tenement would be the land with the right to use the path.

2. Separate ownership or occupation

Put simply: you cannot have a right of use over your own land. Thus the dominant and servient owners or occupiers must be different people.

3. Accommodating the dominant tenement

The right must be for the genuine use and enjoyment of the land itself, and not simply for the personal benefit of the person using it.

Case precedent – Hill v Tupper (1863) 2 H&C 121

Facts: A company leased land adjoining a canal to Hill, giving him the right to use the canal for boat trips. A man who owned a pub nearby then decided to rent out his own boats on the canal for fishing. Hill tried to sue on the basis that the pub owner was interfering with Hill’s property rights. Held: Hill’s rights in the land could not form an easement, because they did nothing more than confer a personal advantage on him and his business.

Principle: The right must accommodate the dominant tenement.

Application: Use this case to show that personal rights conferred upon a property owner will not be sufficient to constitute an easement.

Case precedent – Moody v Steggles (1879) 122 ChD 261

Facts: A right to hang a sign on neighbouring land that pointed to a pub was held to be a valid easement.

Principle: The right must accommodate the dominant tenement.

Application: Use this case in contrast to the finding in Hill v Tupper, to show the difference between situations that will and will not be found to benefit the land, rather than simply its owner.

Up for Debate

The decision in Moody v Steggles is perhaps surprising. The reasoning given for the judgment was that the business would remain on the land for a long time and therefore the land and business were inextricably linked. However, there is an argument to say that not every possible future owner of the land would consider the right to hang signage advantageous to it.

In order for the right to accommodate the dominant tenement, the benefited and burdened land must also be sufficiently close geographically (Bailey v Stephens (1862) 12 CB (NS) 91). If the land benefited is too far away, the suggestion is that the benefit is personal to the landowner, and not to the land. However, this does not necessarily mean that the benefited and burdened land must be immediately adjacent to one another (Pugh v Savage [1970] 2 QB 373).

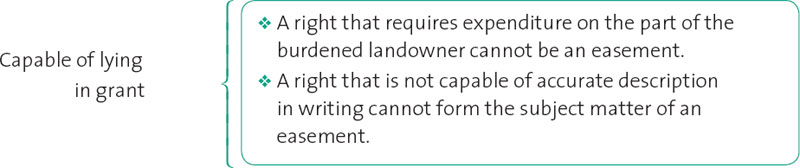

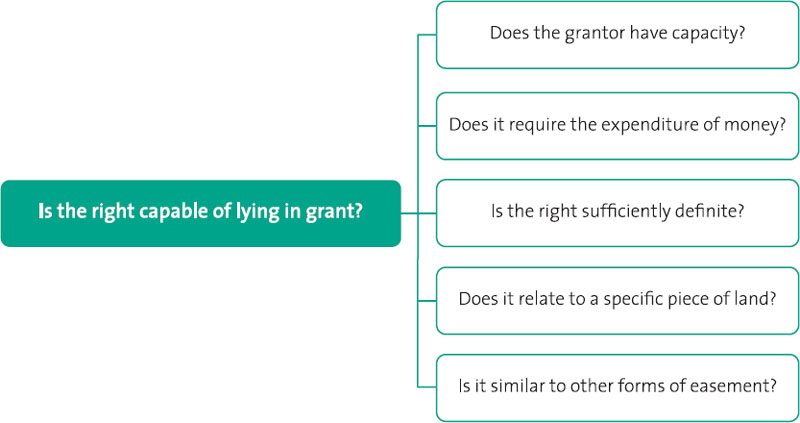

4. The right must be capable of lying in grant

This fourth requirement, which means that the right must be capable of being created by deed, ensures that the nature of the easement is sufficiently certain to be reduced to writing and therefore that it can be enforced and transmitted to a third party. It encompasses the following:

That the person granting the easement has the legal capacity to do so

Aim Higher

This would mean that either an individual capable of owning land or a company would be capable of granting or benefiting from an easement, but the inhabitants of a village or locality, for example, which does not have its own separate legal personality and which is constantly changing and evolving, would not.

That the right relates to the use and benefit of a specific piece of land over a defined area

The effect of this is that an easement for the general use of a number of different pieces of land or the use of an undefined area would not be capable of being an easement.

That the right itself is not too vague

Case precedent – William Aldred’s Case (1610) 9 Co Rep 57b

Facts: An action was brought against a neighbour for building next to the claimant’s house. Whilst the claimant’s right to receive light to the property was recognised, his right to a view was not.

Principle: A right to a view is too vague to constitute an easement.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the fact that where a right is too vague in nature, it cannot constitute an easement.

Case precedent – Browne v Flower [1911] 1 Ch 219

Facts: A landlord had erected an external staircase to a block of flats which passed in between the two bedroom windows of the claimant’s flat. The court was clear in stating that there could be no easement of privacy, however.

Principle: A right of privacy is too vague to constitute an easement.

Application: Use this case to illustrate the fact that where a right is too vague in nature, it cannot constitute an easement.

That the easement does not require the burdened land in the expenditure of money

An easement must not involve a cost to the burdened property.

Case precedent – Regis Property Co Ltd v Redman [1956] 2QB612

Facts: A tenant tried to claim the benefit of an easement against his landlord to supply hot water to the tenant’s property. Held: This could not be an easement because it would impose a financial burden on the landlord.

Principle: An easement must not involve a cost to the burdened property.

Application: Use this case to support your argument that an easement cannot involve expenditure by the burdened property.

Similarity to existing forms of easement

The easement must be analogous to other forms of recognised easement. This does not mean that no new easements can be created, only that the easement must be similar in nature to others already established by case law (Dyce v Lady James Hay).

Points to remember about the nature of easements

The creation of easements

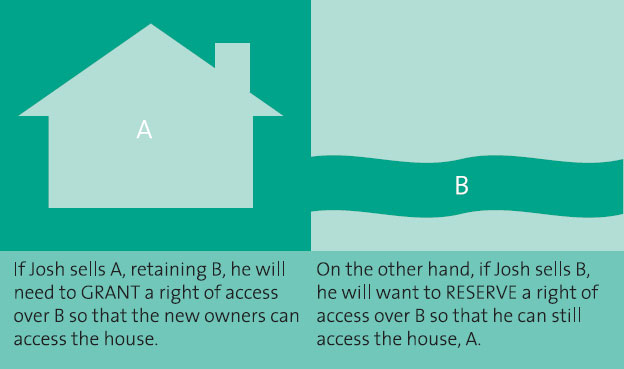

Easements can be created by way of grant or reservation either expressly or impliedly, or through prescription.

Grants and reservations

A grant is where someone gives a right over their own land to another person; a reservation is where someone sells part of their land to a third party, reserving rights over the land sold to benefit the land retained.

Imagine Josh owns two pieces of land, A and B. A has a house on it; B contains a path that runs from the house to the main road beyond Josh’s land.

Josh’s land

Express creation

A legal easement can be expressly created by deed (s 52 LPA 1925), provided that it is granted either for a term equivalent to a freehold (i.e. on a permanent basis) or for a specified term (s 1(2) LPA 1925).

Implied grant or reservation

If there is nothing in writing, the easement may be implied by one of four different methods. These are:

Necessity |

Common intention |

The rule in Wheeldon v Burrows |

Under s 62 LPA 1925 |

Necessity

The courts will imply the benefit of an easement into the deed of purchase of a property where it would otherwise be incapable of use and therefore worthless. Usually this would be in the situation where the land is landlocked (meaning it is inaccessible from the public highway without the benefit of a right of way over adjoining land).

The courts apply the rule stringently and as such, any suggestion of another means of access to the property will defeat the claim.

Case precedent – MRA Engineering Ltd v Trimster Co Ltd [1987] 56 P&CR 1

Facts: The existence of an alternative access to the property in the form of a public footpath over neighbouring land was held sufficient to prevent a claim to an easement of necessity, even though the public footpath did not provide the claimants with any vehicular access.

Principle: Any suggestion of another means of access to the property will defeat the claim.

Application: Use this case to illustrate how stringently the rule relating to easements of necessity will be applied.

Case precedent – Manjang v Dammeh [1990] 61 P&CR 194

Facts: Land adjoining a river was held to be not landlocked and was therefore ineligible for a claim to an easement of necessity because the river was a public highway and, although less convenient, was therefore a perfectly legitimate access to the property.