Duress

10

Duress

Contents

10.3 Duress by threats of violence or other coercion

This chapter deals with the position where one party alleges that he or she only entered into the contract as a result of threats made by the other party. The questions that need to be considered are:

What type of threats will allow a party to escape from a contract? To what extent can threats other than of physical violence have this effect? The relevant question now seems to be simply whether there was illegitimate pressure being used for an improper objective.

What type of threats will allow a party to escape from a contract? To what extent can threats other than of physical violence have this effect? The relevant question now seems to be simply whether there was illegitimate pressure being used for an improper objective.

In what situations may ‘economic duress’ be sufficient to affect the contract? It is important here, as in relation to other types of duress, that the party alleging duress had no real alternative to compliance.

In what situations may ‘economic duress’ be sufficient to affect the contract? It is important here, as in relation to other types of duress, that the party alleging duress had no real alternative to compliance.

Can there be duress where there is a threat to perform an act which involves no breach of the criminal law or civil obligation (such as breach of contract)? The answer seems to be that there can be, but only where the threat is being used for an improper purpose.

Can there be duress where there is a threat to perform an act which involves no breach of the criminal law or civil obligation (such as breach of contract)? The answer seems to be that there can be, but only where the threat is being used for an improper purpose.

What are the remedies for duress? It renders a contract voidable, but does not allow the recovery of damages.

What are the remedies for duress? It renders a contract voidable, but does not allow the recovery of damages.

This chapter is concerned with situations in which an agreement that appears to be valid on its face is challenged because it is alleged that it is the product of improper pressure of some kind. This may take the form of threats of physical coercion or ‘economic’ threats (such as to break a contract), which place pressure on the other party. It seems that explicit threats are needed. Suppose, for example, that a woman has been beaten by her husband in the past, and is then asked by him to sell him her share in the matrimonial home at a gross undervalue. She agrees through fear of what he might do to her, even though he has made no threat to her on this occasion. It seems that this situation cannot be treated as duress, because the threat is implied, rather than explicit.1 English courts would deal with such a situation under the closely related, but conceptually distinct,2 category of ‘undue influence’. This basis for setting aside contracts is dealt with in Chapter 11.

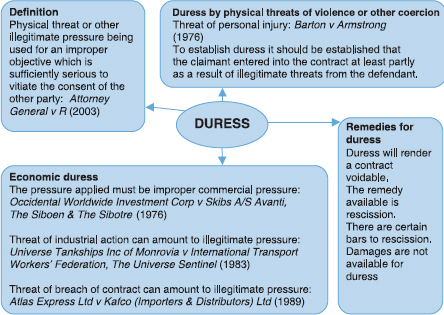

Figure 10.1

One of the problems with economic duress lies in establishing the boundaries of acceptable behaviour of this kind, since economic pressure clearly has a legitimate place within business dealings, and this issue is explored below. If, however, the contract has been entered into as a result of illegitimate threats, it is rendered voidable.3 The courts may be regarded as intervening either because there is no true agreement between the parties, or simply because a person who has been led to make a contract which otherwise he or she would not have done as a result of the exertion of illegitimate pressure should be allowed to escape from it. The latter argument is probably the one which represents the most satisfactory analysis of the situation, but there are many judicial statements which refer to duress ‘vitiating’ the consent of the threatened party. This is discussed further in the next section.

Although it is possible that a person could be physically forced to sign a contract by someone holding their arm and moving it, the most obvious form of duress is where a contract is brought about as a result of a threat of physical injury. A modern example is to be found in Barton v Armstrong,4 where the managing director of a company was threatened with death if he did not arrange for his company to make a payment to, and buy shares from, the defendant. The Privy Council held that the contract could be set aside for duress.

Originally, the nature of the threats which would be treated as constituting duress was very limited; for example, threats in relation to goods were at one time held to be insufficient,5 though even this rule was apparently subject to the exception that money paid under duress of goods could be recovered.6 With the development of the concept of ‘economic duress’ (discussed below, at 10.4), however, a much broader view of the type of threats that can vitiate a contract has been taken. The current approach would seem to be represented by the approach of the Privy Council in Attorney General v R.7

Key Case Attorney General v R (2003)

Facts: A former soldier had made arrangements with a publisher for them to publish an account of his involvement with the SAS in the Gulf War of 1991. This came to the attention of the British Government, and the Attorney General brought an action for breach of contract against the soldier, based on a ‘confidentiality agreement’ that the soldier had signed while still a member of the SAS. The soldier claimed that he had signed the agreement, restricting his ability to publish information about his experiences in the SAS, because if he had not he was threatened with being removed from the SAS (though remaining in the army). Such removal would normally only have taken place as a result of disciplinary action. The case originated in New Zealand, where the trial judge held in the soldier’s favour. The New Zealand Court of Appeal reversed this decision. There was a further appeal to the Privy Council.

The decision was delivered by Lord Hoffmann: his starting point was the decision of the House of Lords in the ‘economic duress’ case, Universe Tankships Inc of Monrovia v International Transport Workers’ Federation.8 He noted that Lord Scarman had identified two elements to duress:9 the first was pressure amounting to compulsion of the will of the victim; the second was the illegitimacy of that pressure. The first element was not in issue in the case, since it was accepted that for the soldier to be returned to a regular army unit would have been regarded in the SAS as a public humiliation. He had no practical alternative to compliance.

As regards the second element, this could be viewed from two aspects:

| (a) | the nature of the pressure; and |

| (b) | the nature of the demand which the pressure is applied to support. |

In relation to the ‘nature of the pressure’, where the threat was to carry out some unlawful act, this would generally lead to the pressure being regarded as ‘illegitimate’. It was not necessarily the case, however, that a threat of a lawful action would be legitimate. This is where the second aspect – that is, ‘illegitimacy’ – needs to be considered. This looks at what the person issuing the threat is trying to achieve. Was their objective a legitimate one? To illustrate the point, Lord Hoffmann quoted from Lord Atkin in Thorne v Motor Trade Association,10 where he said:11

The ordinary blackmailer normally threatens to do what he has a perfect right to do – namely communicate some compromising conduct to a person whose knowledge is likely to affect the person threatened … What he has to justify is not the threat, but the demand of money.

For Thought

Does this mean that a person who signs a contract because the other party threatened to tell his wife about an affair can later escape from the contract on the grounds of duress?

This broad approach to defining the limits of duress must be assumed to be the one which will be adopted by English courts in future (though, of course, as a decision of the Privy Council, Attorney General v R is only of persuasive authority – and since duress was not found, the more general statements could be treated as obiter). The case does not resolve all issues as to the nature of duress, however, and some of these are worth further consideration.

For example, the cases on duress are full of references to the claimant’s will being ‘overborne’ (and this is echoed in the Privy Council’s references to ‘compulsion’). In most cases this will be an inaccurate description of what has happened. The claimant has not been forced to act as an automaton. The decision to make the contract has been taken as a matter of choice. It is simply that the threat which has led to that choice is regarded by the courts as illegitimate, and justifies allowing the party threatened to escape from the consequent contract.12 The fact that this is the basis of the modern doctrine is illustrated by the fact that it was by no means certain in Barton v Armstrong that the threats which were made were the sole reason for the managing director’s decision. The approach of the majority of the Privy Council appears in the opinion of Lord Cross. He noted that, in relation to misrepresentation, there is no need to prove that the false statement was the sole reason for entering into the contract.13 He then commented that:14

Their Lordships think that the same rule should apply in cases of duress and that if Armstrong’s threats were ‘a’ reason for Barton’s executing the deed he is entitled to relief even though he might well have entered into the contract if Armstrong had uttered no threats to influence him to do so …

If this is the case, then it clearly is inappropriate to talk of the will of the person subject to the threats being ‘overborne’. The duress simply becomes a wrongful act of a similar kind to a misrepresentation, which, if it has influenced the other party’s decision to make a contract, provides a basis for that contract being voidable.15

This analysis suggests that the concept of duress focuses on the wrongfulness of the behaviour of the defendant rather than its effect on the claimant.16 Not all commentators would accept that this necessarily follows from the rejection of the ‘overborne will’ approach to duress. Birks and Chin have pointed out that there are authorities which make it clear that duress may be used as a reason to set aside a transaction, notwithstanding the fact that the defendant has acted in good faith.17 If this is so, it cannot be the case that it is the defendant’s ‘wickedness’ which is the reason for treating a contract as voidable; the availability of the remedy must depend on the effect of the defendant’s behaviour on the claimant. This distinction becomes more important once the categories of behaviour which can constitute duress are broadened. When the threats are of physical violence, it is easy to see that criminality as in itself justifying the court’s intervention. When ‘economic’ and other threats are accepted as giving rise to the possibility of duress, the borderline between what is legitimate and illegitimate is narrow, and the likelihood of the threats being made in good faith increases. This leads to the conclusion that although, as indicated in Barton v Armstrong, the threats do not need to be the sole reason for the claimant’s agreement to the contract, they do have to be part of that reason. If a strong-willed claimant has shrugged off the threats, then a claim of duress will not be allowed, even if a reasonable claimant might have been affected by them.18

There are thus two questions to ask in relation to duress: (1) were the defendant’s threats ‘illegitimate’, and (2) was the claimant’s behaviour affected by them? Only if both are answered positively will the conditions arise for the contract to be set aside.19 The claimant may have voluntarily entered into the contract, but would not have done so but for the threats of the defendant.20

10.3.1 IN FOCUS: CAN THERE BE DURESS IF THE CONTRACT WOULD HAVE BEEN MADE ANYWAY?

Lord Cross suggests, in the quotation above, that duress is available even if the contract would have been made without the threats. This surely goes too far. Lord Cross accepts that there must be some causal link between the threats and the contract; it is difficult to understand how, if this is the case, the duress can be regarded as effective if the claimant would have made the contract even if the threats had not been made.21 If we are to accept Lord Cross’ suggestion, however, this would mean rewording the test suggested above (that is, ‘The claimant may have voluntarily entered into the contract, but would not have done so but for the threats of the defendant’) to read: ‘The claimant may have voluntarily entered into the contract, but would not have done so so readily in the absence of the threats of the defendant.’ Lord Scarman, on the other hand, has on more than one occasion emphasised that part of the test of whether duress was operative is whether the claimant had any real alternative but to submit.22 This clearly implies that the contract would not have been made but for the threats, and this seems the more satisfactory approach.23

10.3.2 DIFFICULTIES OF LANGUAGE

The language used in talking of duress does not assist in clarifying these issues. First, the use of the word ‘threat’ carries pejorative overtones, and suggests deliberate bad behaviour on the part of the defendant. The usage is understandable given the origins of duress in putting someone in fear of physical violence. What is, however, meant in the modern context is simply an indication from the defendant to the claimant that if the claimant does not enter into the contract, then the defendant will act in a particular way. The shorthand use of the word ‘threat’ must not be allowed to carry with it any necessary connotation of deliberate wrongdoing.

Second, ‘improper’ or ‘illegitimate’ are the adjectives most commonly used to qualify the defendant’s behaviour. Once again these may carry the implication of wrongdoing by the defendant,24 derived from the origins of duress. It would perhaps be more accurate to refer to behaviour which is ‘inappropriate’. This allows account to be taken of the context in which the behaviour takes place – does it go beyond what a reasonable person would regard as acceptable in all the circumstances?