Discharge by Performance or Breach

14

Discharge by Performance or Breach

Contents

14.7 Some special types of breach

14.9 Effect of breach: right of election

This chapter looks at the termination of a contract by either completion of performance or breach. The most significant issues are:

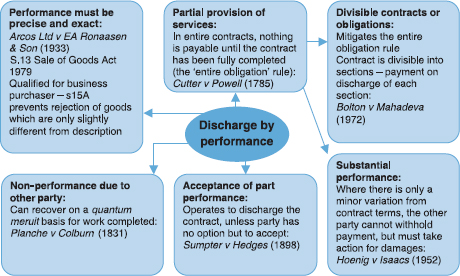

Discharge by performance. The normal rule is that performance must be precise and exact to discharge the party’s obligations. This has the following consequences:

Discharge by performance. The normal rule is that performance must be precise and exact to discharge the party’s obligations. This has the following consequences:

In an ‘entire’ contract payment only has to be made when performance is fully completed – there is no payment for partial performance, unless:

In an ‘entire’ contract payment only has to be made when performance is fully completed – there is no payment for partial performance, unless:

the other party has prevented completion of performance; or

the other party has prevented completion of performance; or

the partial performance has been accepted; or

the partial performance has been accepted; or

the court deems there to have been ‘substantial performance’.

the court deems there to have been ‘substantial performance’.

In a ‘divisible’ contract a party may be entitled to payment for completion of particular stages.

In a ‘divisible’ contract a party may be entitled to payment for completion of particular stages.

Time of performance. If performance is offered late, is the other party obliged to accept it? The general rule is that time is not ‘of the essence’ unless the parties have made it so. In particular:

Time of performance. If performance is offered late, is the other party obliged to accept it? The general rule is that time is not ‘of the essence’ unless the parties have made it so. In particular:

time for payment is not ‘of the essence’ and so late payment is not a ground for rejection; but

time for payment is not ‘of the essence’ and so late payment is not a ground for rejection; but

in relation to all other obligations, the House of Lords has suggested that in commercial contracts time is always of the essence.

in relation to all other obligations, the House of Lords has suggested that in commercial contracts time is always of the essence.

Where time is of the essence, even a very short delay will entitle the other party to terminate.

Where time is of the essence, even a very short delay will entitle the other party to terminate.

Discharge by breach. Breach, however serious, does not automatically terminate a contract – the question is whether it entitles the other party to terminate (‘repudiatory’ breach). The answer is that it only does so if the breach is important – ‘of the essence’. The courts divide clauses into the following.

Discharge by breach. Breach, however serious, does not automatically terminate a contract – the question is whether it entitles the other party to terminate (‘repudiatory’ breach). The answer is that it only does so if the breach is important – ‘of the essence’. The courts divide clauses into the following.

Conditions. Breach of a condition entitles the other party to terminate the contract (as well as claiming damages).

Conditions. Breach of a condition entitles the other party to terminate the contract (as well as claiming damages).

Warranties. Breach of warranty only entitles the other party to claim damages, not to terminate.

Warranties. Breach of warranty only entitles the other party to claim damages, not to terminate.

Innominate terms. The consequences of breach of an innominate term depend on the seriousness of the breach. If it deprives the other party of the main benefit of the contract, it will allow that party to terminate.

Innominate terms. The consequences of breach of an innominate term depend on the seriousness of the breach. If it deprives the other party of the main benefit of the contract, it will allow that party to terminate.

Problem areas.

Problem areas.

Long-term contracts. It may be difficult in a long-term contract to determine what level of breach will be repudiatory.

Long-term contracts. It may be difficult in a long-term contract to determine what level of breach will be repudiatory.

Instalment contracts. Similarly, there may be difficulties in determining how many instalments need to be defective to constitute a repudiatory breach.

Instalment contracts. Similarly, there may be difficulties in determining how many instalments need to be defective to constitute a repudiatory breach.

Anticipatory breach. If a party indicates in advance that it is not going to perform, the other party may elect to terminate immediately, rather than waiting for the date for performance to arrive.

Anticipatory breach. If a party indicates in advance that it is not going to perform, the other party may elect to terminate immediately, rather than waiting for the date for performance to arrive.

This chapter is concerned with ways in which a contract may be discharged, so that the parties no longer have any obligations under it. We have already discussed one way in which this can happen in the previous chapter, under the doctrine of frustration. Contracts may also be discharged by express agreement. If both parties decide that neither of them wishes to carry on with a contract which contains continuing obligations, or in relation to which some parts are still executory, they may agree to bring it to an end early. The only problems which arise here are where the executory obligations are all on one side, so that the party who has completed performance receives no consideration for promising not to enforce the other party’s obligations. This issue has already been dealt with in Chapter 3, in connection with the doctrine of consideration and, in particular, the concept of promissory estoppel, and so is not discussed further here.1 The focus in this chapter is on discharge by performance or by breach: discharge in this context meaning that all further obligations of either or both of the parties are at an end.

Once the parties have done all that they are bound to do under a contract, all ‘primary’ obligations will cease.2 There may, of course, be some continuing ‘secondary’ obligations, such as the obligation to pay compensation if goods turn out to be defective at some point after sale and delivery.

The problem that concerns us here is what constitutes satisfactory performance. If there is some minor defect, does this negative discharge by performance? The practical importance of this relates primarily to the situation where performance by one side gives rise to the right to demand performance from the other. Most typically, this will occur where payment for goods or services is only to be made once the goods have been supplied or the services have been completed. Suppose there is some minor defect in what has been supplied – does this entitle the other party to withhold its own performance by refusing payment?

14.3.1 PERFORMANCE MUST BE PRECISE AND EXACT

The general rule under the classical law of contract is that performance must be precise and exact, and the courts have at times applied this very strictly. Consider, for example, two cases under the Sale of Goods Act 1893. In Re Moore & Co and Landauer & Co,3 the defendants agreed to buy from the plaintiffs 3,000 tins of canned fruit. The fruit was to be packed in cases of 30 tins. When the goods were delivered, a substantial part of the consignment was packed in cases of 24 tins. It was held that this did not constitute satisfactory performance, and the defendants were entitled to reject the whole consignment. Similarly, in Arcos Ltd v EA Ronaasen & Son,4 the buyer had ordered timber staves for the purpose of making barrels. The contract description said that they should be 1/2 inch thick. Most of the consignment consisted of staves which were in fact 9/16 inch thick. They were still perfectly usable for making barrels. Nevertheless, it was held that this did not constitute satisfactory performance, and the buyer was entitled to reject all the staves. In other words, in both these cases, the seller had not performed satisfactorily, and so had not discharged his obligations under the contract.5

Both of these cases turned in part on the interpretation of s 13 of the Sale of Goods Act 1893, which implied an obligation to supply goods which match their contract description. The same provision is now contained in s 13 of the Sale of Goods Act (SGA) 1979.6 In recent years, the courts have been a little more flexible in the application of this section, and s 15A of the 1979 Act now prevents a business purchaser from unreasonably rejecting goods which are only slightly different from the contract description. A similar approach had previously been taken by the House of Lords in Reardon Smith Line Ltd v Hansen-Tangen,7 where a tanker was built at a different yard to that specified in the contract, but in all other respects met the purchaser’s requirements. The House of Lords refused to accept that, by analogy with s 13 of the SGA 1979, the tanker could be rejected for non-compliance with its contractual description. Lord Wilberforce commented that some of the cases on the Act were ‘excessively technical and due for fresh examination’.8

The principle that in general each party is entitled to expect the other to perform to the letter of their agreement remains, however. This was confirmed by the Privy Council in Union Eagle Ltd v Golden Achievement Ltd,9 which concerned a contract for the sale of a flat. Time for performance had been made ‘of the essence’, and under the contract the purchase price was to be tendered by 5 pm on a particular day. In fact, it was tendered at 5.10 pm. The Privy Council confirmed that this entitled the seller to repudiate the agreement and retain the deposit that had been paid. The interests of certainty meant that the court should, in this type of situation, strictly enforce what the parties had agreed.

This approach makes it imperative for the parties to be careful in making their contract to ensure that they allow for flexibility in their performance if that is likely to be a problem for them.10

14.3.2 PARTIAL PROVISION OF SERVICES

In the sale of goods cases, a failure to meet the terms of the contract prevented the seller from claiming any compensation, even in relation to any goods supplied which did match the contract description. The buyer was entitled to withhold performance (the payment of the price) because the seller had failed in its obligations. The same approach is applied to the provision of services. Here, a person may have done a certain amount of work towards a contract, and the question is whether there is any right to claim payment under the contract for what has been done if it does not amount to complete performance.

The starting point for the consideration of this issue is a case that is regarded as the classic example of the common law’s insistence on complete performance.

Key Case Cutter v Powell (1785)11

Facts: The defendant agreed to pay Cutter 30 guineas provided that he served as second mate on a voyage from Jamaica to Liverpool. The voyage began on 2 August. Cutter died on 20 September, when the ship was 19 days short of Liverpool. Cutter’s widow brought an action to recover a proportion of the 30 guineas.

Held: The widow’s action failed. The contract was interpreted as being an ‘entire’ contract for a lump sum, and nothing was payable until it was completed. Thus, even though the defendant had had the benefit of Cutter’s labour for a substantial part of the voyage, no compensation for this was recoverable.

One reason for this rather harsh decision seems to have been that the 30 guineas was about four times the normal wage for such a voyage. The court therefore looked on it as something of a gamble.12 Cutter had agreed to take the chance of a larger lump sum at the end of the voyage, rather than to take wages paid on a weekly basis. This element of the decision was not picked up in later cases, however, and Cutter v Powell was taken to lay down a general rule that in ‘entire’ contracts (that is, where various obligations are to be performed in return for a lump sum) nothing is payable until the contract has been fully completed.

14.3.3 DIVISIBLE CONTRACTS OR OBLIGATIONS13

One way to mitigate this rule, which has the potential to operate very harshly, is to find that the contract is not entire, but divisible into sections, with the completion of each section giving rise to a right to some payment. Thus, if Cutter had been engaged at a certain rate per week, instead of for a lump sum for the whole voyage, his widow would probably have been able to recover for the time he had actually served.14 This is now the standard position in relation to employment contracts: although a salary may be stated on an annual basis, a person who leaves part way through the year will expect to be paid pro rata, even if the contract was for a particular project which has not been completed, or for a fixed period of time which has not expired.15

This will also apply if there are concurrent but independent obligations. In Bolton v Mahadeva,16 there was a contract to (a) install a central heating system, and (b) supply a bathroom suite. The central heating system turned out to be defective, and there was no obligation to pay for this, but the supply of the bathroom suite was severable, and an appropriate proportion of the contract price was recoverable in relation to this obligation.17

14.3.4 NON-PERFORMANCE DUE TO OTHER PARTY

If one party prevents the other from completing the obligations under an entire contract, the party who has partly performed will be able to recover on a quantum meruit basis for the work already done. Thus, in Planché v Colburn,18 the plaintiff recovered £50 towards the work which he had done in writing a book for a series which had then been cancelled by the defendants. The contract price had been £100, but the plaintiff had not completed the book at the time that the defendants brought the contract to an end. A claimant in this situation may also be able to recover damages for consequential losses.

14.3.5 ACCEPTANCE OF PARTIAL PERFORMANCE

If a party accepts partial performance, this may be sufficient in certain circumstances to discharge the other party’s further obligations under the contract, and moreover allow that party to sue on a quantum meruit for the work already done. For example, suppose that goods are to be transported from London to Hull, and the van breaks down en route. If the recipient of the goods agrees to take delivery at Doncaster, the carrier will be able to sue for a proportion of the carriage. In Christy v Row,19 this rule was said to be based on a fresh agreement involving an implied promise to pay for the benefit received. In this case, there was a contract of carriage in relation to seven keels of coal, to be taken from Shields to Hamburg. Seven keels were delivered at Gluckstadt by arrangement with the consignee. It was held that the carrier was entitled to recover freight at the contract rate of £20 per keel.

This exception will not apply, however, if the party effectively has no option but to accept the performance.

Key Case Sumpter v Hedges (1898)20

Held: The Court of Appeal held that the plaintiff could not recover. Collins LJ pointed out, although in some circumstances an agreement to pay might be inferred from the acceptance of a benefit, nevertheless:21

… in order that that may be done, the circumstances must be such as to give an option to the defendant to take or not to take the benefit of the work done.

It would not be reasonable to expect the defendant to keep on his land a building which was in an incomplete state, and would constitute a nuisance.

14.3.6 SUBSTANTIAL PERFORMANCE

The principle of ‘substantial performance’ has the potential to constitute a more general exception.22 It is based on the idea that where there is only a minor variation from the terms of the contract, the other party cannot claim to be discharged, but must rely on an action for damages for breach. The origins of it can be traced to Boone v Eyre,23 a case concerning the sale of a plantation, together with its slaves. It was suggested by Lord Mansfield CJ that the fact that the seller could not establish ownership of every single slave stated to be included in the contract would not prevent him from recovering payment from the buyer under the agreement. The principle is, however, stated most clearly in Dakin v Lee24 and Hoenig v Isaacs.25

Key Case Dakin v Lee (1916)

Facts: The contract was for the repair of a house. The work was not done in accordance with the contract. In particular, the concrete underpinning was only half the contract depth; the columns to support a bay window were of 4 inch diameter solid iron, instead of 5 inch diameter hollow; and the joists over the bay window were not cleated at the angles or bolted to caps and to each other. The official referee found that the plaintiffs had not performed the contract, and therefore could not claim for any payment in respect of it. The plaintiff appealed.

Held: The Court of Appeal noted that there was a distinction between failing to complete26 and completing badly. Here, the contract had been performed, though badly performed, and the plaintiff could recover for the work done, less deductions for the fact that it did not conform to the contract requirements.

A similar approach was taken in Hoenig v Isaacs, where there were found to be defects (which would cost £55 to repair) in work done in redecorating a flat. The total contract price was £750. It was held that there was substantial performance, and that the plaintiff could recover the contract price, less the cost of repairs.27

For Thought

If the repairs in Hoenig v Isaacs had cost £255 rather than £55, do you think this would have made a difference to the decision? If so, where would the ‘tipping point’ be between substantial and non-substantial performance as regards the cost of repairs?

The Court of Appeal refused to apply substantial performance in Bolton v Mahadeva,28 as regards the obligation to install a central heating system. The system as fitted gave out much less heat than it should have done, and caused fumes in one of the rooms. Although the complete system had been fitted, it did not fulfil its primary function of heating the house, and so the installer was not allowed to recover.

The doctrine of substantial performance appears to be infrequently used and may not be of great significance in practice. That it is still available, however, was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Young v Thames Properties Ltd.29 The contract was for the construction of a car park. The main complaints of the defendant (the car park owner), who was resisting paying for the work, were that the sub-base consisted of limestone scalpings 30mm deep, when, according to the contract, they should have been 100mm deep, and that the wrong grade of tarmacadam had been used as the top surface. The judge accepted evidence that these defects made little practical difference to the quality of the car park, and that the cost of remedying them (which would have involved taking up and relaying the whole area) would have been disproportionate. He held that the plaintiff was entitled to the contract price, less the amount which he had saved through the various failures to comply with the specifications. The Court of Appeal confirmed that the doctrine of substantial performance should be applied as laid down in Dakin v Lee, and that, in particular, there was a difference between work which was abandoned and work which was completed and done badly. Approval was given to the following statement in the headnote to Dakin v Lee:30

Figure 14.1

In the end, however, ‘the essence of the doctrine of substantial performance is that it depends on the nature of the contract and all the circumstances which arise in the present case’. The question of whether there had been substantial performance was one of fact and degree and, therefore, essentially an issue for the trial judge. On the facts, the judge had been entitled to conclude that the various defects which had been identified did not prevent a finding that there had been substantial performance; nor was there anything wrong with his approach to the calculation of the damages.

The same approach was adopted by the Court of Appeal in Williams v Roffey Bros & Nicholls (Contractors) Ltd.31 Applying Hoenig v Isaacs, it held that the trial judge had been entitled to find that there had been substantial completion of the work on eight flats, entitling the plaintiffs to payment.

Being ready to perform a contract (‘tender of performance’) is generally treated as equivalent to performance in the sense that, if it is rejected, it will lead to a discharge of the tenderer’s liabilities. Thus, as s 27 of the SGA 1979 puts it, where the expectation is that goods will be paid for on delivery:

… the seller must be ready and willing to give possession of the goods to the buyer in exchange for the price and the buyer must be ready and willing to pay the price in exchange for the possession of the goods.

14.4.1 DEFINITION OF TENDER

What amounts to satisfactory ‘tender’, so as to bring the above principle into play? This will largely depend on the terms of the contract, but something of the approach of the courts can be seen from Startup v Macdonald.32 The plaintiff agreed to sell 10 tons of oil to the defendant. Delivery was to be ‘within the last 14 days of March’. Delivery was in fact tendered at 8.30 pm on 31 March, which was a Saturday. The defendant refused to accept or pay for the goods. It was held that provided that the seller had actually found the other party, and that there was time to examine the goods to check compliance with the contract, this was a satisfactory tender.

From this it will be seen that the requirements are that the tender should meet the strict terms of the contract and that it should be brought to the attention of the other party in time for any rights which might arise on tender to be exercised.

14.4.2 TENDER OF MONEY

If a debtor tenders payment, and this is not accepted, this does not cancel the obligation to pay. The debtor, however, is not obliged to attempt to pay again, but can wait until the creditor calls for payment.

The exact amount must be tendered. There is no legal obligation to give change, though of course in the majority of situations the creditor will be quite happy to do so.

There are particular statutory rules as to the maximum amounts of particular types of coin which will constitute ‘legal tender’.33

Is the time for performance important? Is time, as the courts put it, ‘of the essence’? The common law said that it was, unless the parties had expressed a contrary intention. Equity took the opposite view, so that time was not of the essence unless the parties had specifically made it so. The equitable rule was given precedence in s 21 of the Law of Property Act 1925, so that where under equity time is not of the essence, contractual provisions dealing with time should be interpreted in the same way at common law. Note also that s 10(1) of the SGA 1979 states that:

Unless a different intention appears from the terms of the contract, stipulations as to time of payment are not of the essence of a contract of sale.34

The reference to the intention of the parties which appears in this section is of general application, as was confirmed by the House of Lords in United Scientific Holdings Ltd v Burnley Borough Council.35 Refusing to be bound by the position as regards the common law and equitable rules prior to 1873, the House preferred to look at the nature of the contract itself. The dispute concerned the operation of a rent review clause within a 99 year lease. The House held that time was not of the essence as far as the activation of the review machinery was concerned, so that the landlord was able to put it in motion even though he had just missed the 10-year deadline specified in the lease itself. In coming to this conclusion, the House expressed approval for the following statement in Halsbury’s Laws of England:36

The first element of this paragraph is unproblematic. As regards the second category, however, it is unclear whether commercial contracts should be regarded as always falling within its scope. In Bunge Corp v Tradax SA,37 there are statements in both the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords that, in commercial contracts, stipulations as to time are usually to be treated as being ‘of the essence’.38 This seems to suggest a prima facie rule which is contrary to the presumption in Halsbury that time is not usually of the essence. The statements in Bunge v Tradax are somewhat diffident, however, and the House at the same time gave approval to the statement in Halsbury.39 The best approach is probably that the issue should be determined on the basis of the commercial context of the particular contract under consideration rather than being subject to any specific presumption. The judicial statements are sufficiently vague to allow such an approach.40

Where time is not initially of the essence, it seems that it may become so by one party giving notice. This is what happened in Charles Rickards Ltd v Oppenheim,41 the facts of which are given in Chapter 3.42 This possibility appears to arise as soon as the contractual date for performance has passed. This was the view taken by the Court of Appeal in Behzadi v Shaftesbury Hotels Ltd,43 which was a contract for land. The court held that if the contract contained a specific date for performance, even though this was not of the essence, there was nevertheless a breach of contract as soon as that date had passed, and the party not in breach was entitled to serve a notice immediately making time of the essence. As Purchas LJ put it:44

I see no reason for the imposition of any further period of delay after the breach of contract has been established by non-performance in accordance with its terms before it is open to a party to serve such a notice. The important matter is that the notice must in all the circumstances of the case give a reasonable opportunity for the other party to perform his part of the contract.

Only after that period had expired would the party who has issued the notice be entitled to treat the contract as repudiated by the other side’s failure to perform. In coming to this conclusion, the court disapproved dicta in British and Commonwealth Holdings plc v Quadrex Holdings Inc,45 which suggested that there must be an unreasonable delay before the right to give notice making time of the essence arises. Since both these cases are Court of Appeal decisions, the latter one, Behzadi v Shaftesbury Hotels Ltd, should be taken to prevail, pending a ruling by the House of Lords.

A breach of contract will have a range of consequences. It may entitle the innocent party to seek an order for performance of the contract, to claim damages, or to terminate the contract, or some combination of these. It is termination that we are concerned with in this chapter,46 since this will also entail the discharge of future obligations. Where the innocent party terminates a contract as a result of a breach by the other side, it is in fact likely to be indicating three things: (1) that it will not perform any of its outstanding obligations under the contract; (2) that it will not expect the other party to perform any of its outstanding obligations, and will reject performance if it is tendered; and (3) that it may seek financial compensation (damages) for losses resulting from the other party’s breach.47

14.6.1 EFFECT OF BREACH