DEVOLUTION AND INDEPENDENCE

8.1 Historical overview of the formation of the United Kingdom

Wales

8.1.1 King Edward I of England undertook a defining military conquest of large parts of Wales between 1277 and 1283. Since then, the Prince of Wales has always owed allegiance (and has most often been a member of) the English monarchy.

8.1.2 The Laws in Wales Act 1536 ensured that Welsh subjects of the English Monarch had rights equal to those in England and Ireland (Scotland had its own Government and Monarch at that time). Welsh representatives were also empowered to attend the House of Commons in Westminster as a result of the 1536 Act.

8.1.3 Courts administering English laws were created in each county of Wales, following further legislation from Westminster in 1543.

8.1.4 The common law of England and Wales has developed in tandem ever since.

Scotland

8.1.5 England never militarily overpowered Scotland in a way that resembled English domination of Wales. England and Scotland united their respective Crowns in 1603, when James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of England, becoming James I of England and VI of Scotland.

8.1.6 England and Scotland, however, retained separate Parliaments until 1707, when the Scottish Parliament passed an Act of Union with England, to reciprocate with the Act of Union with Scotland that was passed by the Westminster Parliament in 1706.

8.1.7 These Acts of Union, as they are collectively known, abolished the Scottish Parliament, and the Westminster Parliament became the sole (at that time) and dominant (as it still is) legislative forum in the British Isles.

8.1.8 While there were Scottish representatives as Members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords from that point onwards, as part of the political settlement that went along with the Acts of Union themselves, as Neil Parpworth notes, those ‘laws in either kingdom which were contrary to or inconsistent with the articles of the Union were thereby abolished’.

8.1.9 The substance of Scottish private law, and the structures of the Scottish civil and criminal courts have remained distinct and unique – many would say markedly different – from the Anglo-Welsh common law and court system ever since, as the Acts of Union preserved the Scottish judicial and doctrinal preferences in place at the time.

Northern Ireland

8.1.10 Historically, Ireland as a whole had been subject to English and other influences since the 12th century, and effective government by Britain (comprising England, Wales and Scotland) following the Acts of Union from 1706/7 onwards.

8.1.11 As Neil Parpworth has observed, for example, in 1720 ‘the British Parliament passed the Declaratory Act in which it was declared that it had the power to legislate for Ireland’. Later in the 18th century, Henry Grattan led an Irish Parliament which had had legislative powers restored to it in 1782, but this was abolished under the Union with Ireland Act of 1800, passed by the British Parliament. The trigger for this was an uprising by a group called the United Irishmen in 1798. After this point, and on 1 January 1801, as enacted in Article 1 of the Union with Ireland Act 1800, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was established. Some Irish MPs represented the country in the Westminster Parliament.

8.1.12 The story of the relationship between Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom in the 19th century is the story of a move to increasing demands for ‘Home Rule’ – the term then given to Irish independence. This movement was principally led in the later 19th century by the Irish National League leader Charles Stewart Parnell, but ‘Home Rule’ was essentially frustrated.

8.1.13 After the end of the First World War, British politicians could, however, no longer ignore Irish demands for self-governance. There were though some who would not support an entirely independent Ireland – with Ulster Unionists chief amongst them. Edward Carson, a staunch supporter of the United Kingdom, secured a compromise with those senior British politicians who were in favour of a fully independent Ireland under Home Rule.

8.1.14 Unfortunately for the course of British and Irish history, the divide between Home Rule and Ulster Unionism was motivated by rampant sectarianism – that is, extremist views against either Christian Catholicism or Christian Protestantism. The historical roots of this cultural and religious divide ran very deep – based on remembered bloodshed perpetrated in Ireland in the name of religious difference over centuries. Ulster Unionism for the majority of the 20th century was characterised by anti-Catholic sectarianism – but in 1920, it was a sufficiently powerful political force that Edward Carson and his allies could secure ‘Partition’ in Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act. A devolved legislature for Southern Ireland never actually sat, after an Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922, which created the Irish Free State (all of Ireland bar the six of nine Ulster counties that now constitute Northern Ireland), was brought about by a Civil War in Ireland. The Irish Free State became Eire in 1937, through the creation of a new written constitution, and so rejecting UK dominion status (and as a by-product, ensuring Eire neutrality in the Second World War); and in 1949 Eire became the Republic of Ireland.

8.1.15 Northern Ireland (the six Protestant-dominated of nine counties in the historical Irish province of Ulster) had its own Parliament with legislative powers, until these were removed by the Westminster Parliament in 1972 (see below).

8.2 Key developments in the late 20th century

Wales

8.2.1 In 1973, a Royal Commission on the Constitution recommended that there be some degree of devolution in Wales.

8.2.2 The Wales Act 1978 was put on the statute book to create a Welsh executive to govern more locally in Wales, with directly elected officials to administer laws created in Westminster in a Welsh setting. But this plan did not come to fruition, despite the 1978 Act being passed; because a key referendum, the outcome of which the proposals rested upon, was heavily in favour of the status quo in maintain a single central executive.

8.2.3 It was the New Labour Government of 1997 that had included more legislative devolution for Wales in its manifesto, prior to its landslide General Election success. As such, the Government of Wales Act received Royal Assent in July 1998. The effects are discussed below.

Scotland

8.2.4 Much as in Wales, while momentum toward Scottish devolution grew in the late 20th century, and again, while there was a Scotland Act of 1978 in place to deliver some real devolved legislative powers to a Scottish Government, it too was dependent on the favourable outcome of a referendum, though the referendum itself needed a turnout of at least 40% of voters to be binding.

8.2.5 Whilst a majority of those eligible to vote did vote in favour of the move towards devolution that would have in place under the 1978 Act, fewer than 40% of the eligible electorate actually voted in the referendum, so the plans for Scottish devolution at that point again, as in the same period in Wales, never came to fruition.

8.2.6 Again, in a parallel fashion to that in Wales, the election of a Labour Government in May 1997 led to the creation of the Scotland Act 1998, which is also described below.

Northern Ireland

8.2.7 Legislative powers of the Northern Ireland Parliament were revoked by the Westminster Parliament in 1972. Sectarian divisions had created a situation in Northern Ireland whereby the terrorist group known as the Irish Republic Army (IRA) and their allies, seeking a United Ireland entirely free from British influence, had perpetrated atrocities in ‘the Troubles’ of the 1960s and early 1970s. Radical Protestant Ulster Unionist-allied groups also perpetrated atrocities of their own devising against the Catholic population in Northern Ireland. Sadly this mutual bloodshed lasted until the late-1990s, despite political and diplomatic efforts by the Governments of both the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland.

8.2.8 In 1997 the IRA and Unionist terrorist organisations entered into a ceasefire that has been observed ever since, at least by the majority of the groups that had been engaged in sectarian violence; and this ceasefire allowed ongoing peace talks to include the Irish nationalist political party, Sinn Féin.

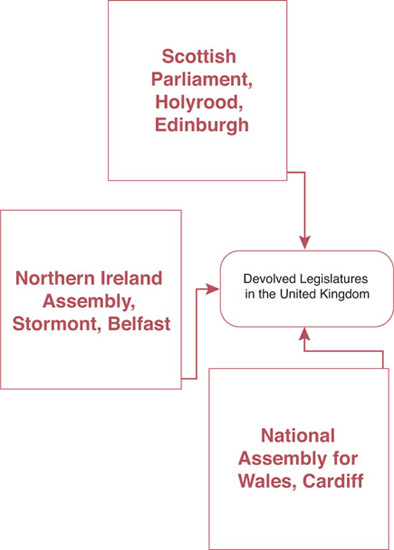

8.2.9 These peace talks led to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, known formally as the Belfast Agreement. In turn this led to the Northern Ireland Act 1998 (see below), and the creation of a devolved legislature in the form of the Northern Ireland Assembly, at Stormont.