Credit Cards

Introduction

Credit cards are a significant socio-economic phenomenon. In 2008, consumers used almost 1.5 billion credit cards—more than 12 cards per household—to purchase over $2 trillion of goods and services. The average household spent $18,000 in credit card transactions, which is more than 35 percent of median household income in the U.S. Credit cards are also the largest source of non-secured credit. Credit card debt amounted to $976 billion in 2008.1

Credit cards have been the subject of heated political debate for many years.2 Recently, in the wake of the financial crisis, Congress passed the Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility, and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009, which imposes substantial constraints on credit card issuers. The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 established a new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau charged with more closely overseeing consumer credit markets, including the credit card market.

A. Contract Design

The common credit card contract is highly complex. The fees and interest rates are staggering in both number and complexity. There are annual fees, cash-advance fees, balance-transfer fees, foreign currency-conversion fees, expedited-payment fees, no-activity fees, late fees, over-limit fees, and returned-check fees. As for interest rates, in addition to the primary, long-term interest rate, there are introductory (teaser) rates, rates on balances transferred from other cards, rates on cash advances, and default interest rates. That’s not all: Most of these fees and interest rates are variable and multidimensional, triggered by complex sets of conditions.

Credit card contracts also feature deferred costs and accelerated benefits. The multiple price dimensions of the credit card do not always track the issuer’s underlying cost structure. Rather, issuers set lower prices for salient, usually short-term dimensions and higher prices for non-salient, usually long-term dimensions. Consider, for example, the prevalence of low, even zero, introductory interest rates alongside much higher long-term interest rates—not to mention the even higher default interest rates. Similarly, we often see no per-transaction fees, and even negative per-transaction fees positioned as benefits provided by loyalty programs—alongside high currency-conversion fees, late fees, and over-limit fees.

B. Contract Design Explained

Why do credit card contracts couple a high level of complexity with cost deferral? To find out, let’s first explore a series of standard, rational-choice theories. These theories do a better, though not completely satisfactory, job of explaining the complexity dimension.

Complexity plays into the imperfect rationality of cardholders. As we saw in the previous chapter, the imperfectly rational cardholder deals with complexity by ignoring it. Decision problems are simplified by ignoring non-salient price dimensions and “guesstimating,” rather than calculating, the impact of the salient dimensions that cannot be ignored. In particular, the imperfectly rational cardholder’s limited attention and limited memory might result in the exclusion of certain price dimensions from consideration. And limited processing ability might prevent cardholders from accurately aggregating the different price components into a single, total expected price that would serve as the basis for choosing the optimal card.

Increased complexity may be attractive to issuers, as it allows them to hide the true cost of the credit card in a multidimensional pricing maze. An issuer who understands the imperfectly rational response to complexity can leverage complexity to create an appearance of a lower total price without actually lowering the price. For example, if the currency-conversion fee and the cash-advance fee are not salient to cardholders, issuers will raise the magnitude of these price dimensions. Increasing these non-salient prices will not hurt demand. On the contrary, it will enable the issuer to attract cardholders by reducing more salient price dimensions or by increasing more salient benefit dimensions, such as reward points and frequent-flyer miles. As discussed in the previous chapter, this strategy depends on the existence of non-salient price dimensions. When the number of price dimensions goes up, the number of non-salient price dimensions can also be expected to go up. Issuers thus have a strong incentive to increase complexity and multidimensionality.

The behavioral-economics explanation for deferred costs is based on evidence that future costs are often underestimated. When future costs are underestimated, contracts with deferred-cost features become more attractive to cardholders and thus to issuers. Underestimation of future costs can be traced back, in large part, to two underlying cognitive biases; myopia and optimism. Myopic cardholders focus on short-term benefits and pay insufficient attention to long-term costs. Optimistic cardholders underestimate their future borrowing and, as a result, underestimate the significance of the many credit card price dimensions that are contingent upon borrowing. There are two main reasons why cardholders might underestimate their future borrowing: (a) they might underestimate their self-control problems, and (b) they might underestimate the likelihood of contingencies bearing economic hardship. Optimism about one’s self-control and about one’s future financial condition drive the underestimation bias.

When non-salient, long-term dimensions are underestimated or ignored by cardholders, issuers may raise prices on these dimensions of the credit card contract. In a competitive market, the high prices on these long-term dimensions will pay for low prices on the salient, short-term dimensions that drive demand for the credit card product. This interaction between consumer psychology and market forces produces contracts with deferred costs and accelerated benefits.

So far, the credit card contract has been portrayed as a tool designed to exploit consumer biases. Interestingly, to the extent that the credit card market is competitive, issuers must exploit consumers’ imperfect rationality in order to survive in this market. Issuers that do not take advantage of consumer biases and, instead, offer lower long-term prices with reduced short-term perks would not succeed in the marketplace. Consumers would fail to appreciate the value of reduced long-term prices and would take their business elsewhere. On the other hand, competition could have a positive effect by creating incentives for issuers to educate consumers and reduce the biases and misperceptions that give rise to excessive complexity and cost deferral.

C. Welfare Implications

The imperfect rationality of cardholders and the contractual design that responds to this imperfect rationality impose several welfare costs. First, the complexity of credit card contracts makes it difficult for consumers to comparison-shop effectively, thus hindering competition in the credit card market. Second, since credit card pricing is, in many cases, salience-based rather than cost-based, these prices provide inefficient incentives for credit card use. Zero annual and per-transaction fees, coupled with benefits programs, result in the creation of too many credit cards and excessive use of these cards. Teaser rates lead to excessive pre-distress borrowing, which renders the consumer more vulnerable to financial hardships. Moreover, salience-based pricing creates an appearance of a cheaper product without actually offering a cheaper product, resulting in artificially inflated demand for credit cards.

Efficiency isn’t the only thing threatened by the distorted pricing in the credit card market. Since the high borrowing-related costs are paid by financially weaker cardholders, the behavioral market failure also raises distributional concerns.

D. Policy Implications

The welfare costs cited above provide a prima facie case for legal intervention. Cardholder misperceptions that underlie the identified welfare costs also qualify the no-intervention presumption of the freedom-of-contract paradigm. If a contracting party misconceives the future consequences of the contract, then the normative power of contractual consent is significantly weakened.

This chapter focuses on one, common regulatory technique; disclosure mandates. The behavioral-economics model challenges the conventional disclosure approach, which focuses almost exclusively on disclosure of product-attribute information such as interest rates and fees. Issuers should also be required to disclose product-use information. If a consumer mistakenly believes that he or she will never make a late payment, disclosing the magnitude of the late fee will not affect the consumer’s credit card choice. Because issuers know more about a consumer’s card-related use patterns than the consumers themselves do, they should be required to share this information. Issuers should tell consumers how likely they are to pay late.

Legislators and regulators are beginning to recognize the importance of product-use disclosures. The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 imposes a general duty, subject to rules prescribed by the new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, to disclose information, including usage data, in markets for consumer financial products.3 And Federal Reserve Board regulations, which took effect along with the CARD Act implementing rules, require that issuers disclose, on the monthly statement, monthly and year-to-date totals of interest charges and fees—a disclosure that combines product-attribute and product-use information.4 These are important first steps.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows:

• Part I provides background on the credit card market.

• Part II describes the common credit card contract, focusing on the two identified design features: complexity and cost deferral.

• Part III evaluates possible rational-choice, efficiency-based explanations for the identified design features.

• Part IV develops an alternative, behavioral-economics theory of contract design in the credit card market.

• Part V identifies the welfare costs of cardholder misperception and of contracts designed in response to these misperceptions.

• Part VI discusses market solutions, specifically consumer-friendly credit cards and debit cards.

• Part VII explores legal policy responses, focusing on disclosure regulation.

I. The Credit Card Market

A. Two Functions

What is a credit card? It is a flat, 3⅜” by 2⅛” piece of plastic engraved with a name and an account number. This “plastic,” as it’s commonly known, allows its holder to perform two distinct tasks; to transact quickly and efficiently, and to borrow—to finance a purchase, business, or way of life. Though offered through the same piece of plastic, transacting and financing functions constitute two distinct services provided by the credit card issuer.

Of course, the credit card holder is not required to make use of both functions. Some transact but do not borrow, using the credit card only as a method of payment. While the number of people who use a credit card in this way is not insignificant, most cardholders use both the transacting and financing services provided by their cards.5

B. A Brief History

The term “credit card” was coined back in 1887 by Edward Bellamy in his utopian socialist novel, Looking Backward. Bellamy provided a futuristic account of the year 2000, when credit cards had entirely supplanted cash. He was not off by much. In 2008, payment cards (credit cards, charge cards, and debit cards) accounted for more than 50 percent of transaction volume in the U.S.6

The history of consumer credit in the more modern world began in the early twentieth century, when Sears Roebuck and Company started lending money to its customers so that they could buy the Sears products. Thus, the merchant card (or retail card) was born. Back then, however, the merchant card was only accepted by the merchant that provided the specific card.7

The path to the contemporary credit card wound its way through the so-called Travel & Entertainment (T&E) cards, which were special-purpose charge cards that, in time, evolved into all-purpose cards. The Diner’s Club card led the way in 1949, followed by American Express and Carte Blanche, which entered the market in 1958. The T&E cards, while gradually evolving into all-purpose cards, remained charge cards, rather than credit cards, meaning that the balance on these cards was due in full at the end of each month.8

In the mid-1960s, with the advent of the Visa and MasterCard systems, the modern credit card was born, combining the all-purpose feature of the evolved T&E cards with the credit feature of the merchant cards. The Visa and MasterCard bankcards grew rapidly as they added more and more bank issuers and merchants to their networks. In 1985, Sears Roebuck and Company introduced its own all-purpose credit card, the Discover card. American Express joined the credit card scene with its Optima card in the late 1980s. As Sullivan, Warren, and Westbrook put it: “By the 1990s the all-purpose card gained dominance over traditional store cards, making it possible for millions of card holders to charge anything from their dental fillings to their parking tickets.”9

For credit card issuers, the initial steps on the road to success were shaky. With strict usury laws in place that mandated caps on interest rates, issuers initially lost money on their credit card business. The banking industry eventually overcame the strict interest-rate ceilings in an ingenious way. Instead of lobbying each state legislature for more lenient usury laws, the industry targeted, in the Federal courts, the jurisdictional issue of the “exportation” of interest rates, the question being “which state’s usury ceiling constrains the interest rate if a bank located in one state issues a credit card to a consumer in a different state.”10

In 1978, the exportation question reached the United States Supreme Court. The Court, in Marquette National Bank v. First of Omaha Service Corporation, ruled that the applicable usury ceiling was the one set by the state in which the issuing bank was located. In effect, the Supreme Court “gave banks the option of shifting their credit card operations to wholly owned subsidiaries situated in states without usury laws.” The Marquette decision fired the opening shot in the inter-state race to attract credit card issuers. To win this race, or to, at minimum, prevent an exodus of banks, many states substantially increased their interest caps or revoked their usury laws altogether. Thus, the Marquette decision produced a functionally deregulated credit card market. Moreover, the decision enabled credit card issuers to operate on a national level and thus to enjoy economies of scale.11

The sky-high inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s lifted the final barrier to the profitability of the credit card industry. With the effective abolition of usury laws, credit card interest rates rose to match the high inflation rates. In fact, the causation probably worked in both directions; the high inflation rates were likely instrumental in bringing about the legal rulings (specifically the Marquette decision) that triggered the abolition of usury ceilings. Whatever the sequence, credit card interest rates rose with inflation.12

As high inflation justified raising interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the subsequent decline in the inflation rate starting in 1982–83 might have been expected to bring about a reduction in those rates. This reduction, however, never came or, more accurately, was very late to arrive (see below).13

The early history of the credit card industry was marked by declining costs and “sticky” interest rates. The high interest rates, which stubbornly failed to keep pace with the declining cost of funds, allowed credit card issuers to offer more credit and to target less credit-worthy consumers.14 The result: An explosion of consumer credit, which led to a dramatic expansion of consumer debt and also to an increase in consumer bankruptcy rates.15

The more recent history of the credit card industry, starting in the early 1990s, has been marked by the technological advances that made risk-based pricing possible. The ability to match interest rates (and other price dimensions) to borrower risk allowed issuers to serve less creditworthy borrowers, thus fueling the continuing expansion of credit cards. Risk-based pricing implies lower interest rates for low-risk consumers and high rates for high-risk consumers. It does not, however, imply a reduction in average rates. But such a reduction did finally occur, starting in the early 1990s, as competition focused on the interest rate, which became more salient to consumers.16

C. Economic Significance

Credit cards are a major method of payment, and their prevalence and importance is only growing. By 1995, credit cards had already surpassed cash as a method of payment. In 2008, consumers used almost 1.5 billion credit cards (more than 12 cards per household) to purchase over $2 trillion of goods and services. The average household completed $18,000 of credit card transactions, over 35 percent of the median household income.17

The credit card industry has experienced a significant growth rate by any measure, be it transaction volume, number of cards in circulation, or outstanding balances. While in 1970 only 16 percent of households had credit cards, 73 percent of households had at least one credit card in 2007. The average monthly household charge was over $1,500 in 2008, as compared to only $165 (in current dollars) in 1970. And the ratio of charges-to-income grew from just under 4 percent in 1970 to about 35 percent in 2008. Credit cards’ piece of the total consumer spending pie has increased substantially. A growing body of evidence suggests that they have also contributed to the increase in the size of the consumer spending pie.18

Not only do credit cards encourage spending, they encourage borrowing as well. As noted by Sullivan, Warren, and Westbrook:

Credit card debt has become as much a part of American life as has the credit card itself…. Of the three-quarters of all households that have at least one credit card, three out of four of them also carry credit card debt from month to month…. Increasingly, … [Americans] do not pay [with their credit cards]—they finance. Quietly, without much fanfare, Americans have taken to buying school shoes and pizza with debt—and paying for those items over months or even years.19

Credit cards are now the leading source of unsecured consumer credit/debt. And consumers aren’t the only ones who use credit card financing; many self-employed owners of small businesses turn to high-interest credit card debt to finance their businesses.20

Total credit card borrowing in 2008 amounted to $976 billion. The average credit card debt per household in the U.S. was over $8,300 in 2008. If we focus on the 73 percent of households with credit cards, average debt per household rises to over $11,400. The average debt among the 60 percent of households that carry credit card debt was over $19,000 in 2008. The median credit card debt-to-income ratio was 16.5 percent across all households, 22.7 percent for households with credit cards, and 37.8 percent for households that carry credit card debt. Clearly, credit card debt imposes a substantial burden on many households.21

It is not surprising, then, that credit card debt plays a notoriously important role in consumer bankruptcy. Credit card defaults are highly correlated with personal bankruptcies. Based on their empirical investigation of consumer bankruptcy filings, Sullivan, Warren, and Westbrook conclude that “[a]s the fastest growing proportion of consumer debt, credit card debt has led the way to bankruptcy for an increasing number of Americans….” Three independent statistical studies, by Ronald Mann, by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi, and by Michelle White, suggest a causal relationship between credit card debt and consumer bankruptcy filings.22

D. Market Structure

1. Participants

The credit card market is divided among the major credit card brands: Visa, MasterCard, American Express, and Discover. The bankcard brands, Visa and MasterCard, share a common and more complex structure. Until recently, they were joint ventures of banks, comprising thousands of distinct issuers. In 2006, MasterCard registered as a private-share corporation, owned by its member banks. Visa followed suit in 2008. While many of these bank issuers operate only at the local level, a significant number of others participate at the regional and national levels. In the 1990s, a new group of players entered the credit card scene; non-bank issuers, such as AT&T. While technically these non-bank issuers are necessarily affiliated with a Visa or MasterCard issuing bank and the issued credit card is actually a co-brand card, as in the case of AT&T and MasterCard, the major strategic decisions are undertaken by the non-bank issuer.23

Regarding the bankcard brands, it is interesting to note that the Visa and MasterCard associations are quite decentralized. Lawrence Ausubel observed that “most relevant business decisions are made at the level of the issuing bank [rather than at the Visa or MasterCard organizations level]. Individual banks own their cardholders’ accounts and determine the interest rate, annual fee, grace period, credit limit, and other terms of the account.”24

Even so, the Visa and MasterCard organizations play an important role. They set the interchange fee for the transfer from the merchant’s bank to the card-issuing bank. They promote the company’s brand name through advertising. And they lead the competition with the other bankcard brand as well as with the non-bankcard brands.25

2. Competition

There are two intertwined levels of competition within the credit card industry; brand-level competition and issuing-level competition.

At the upper level, the major credit card brands—especially Visa, Master-Card, American Express, and Discover—compete among themselves. Visa is the industry leader in terms of both charge volume and credit extended, with MasterCard following closely behind. American Express and Discover occupy the more distant third and fourth places, respectively.26 The evidence regarding the intensity of competition at this level is mixed. While the four brands clearly compete against each other, the series of antitrust challenges against Visa and MasterCard suggests that the leading brands have taken steps to limit competition at the network level.27

Competition at the issuing level is more robust, although there is evidence that competition even at this level is less than perfect. While it may appear that thousands of banks, along with American Express and Discover (as issuers), compete for consumers, the fact is that a relatively small number of large banks control most of the market. There is also mixed evidence about the competitive effect of switching costs. While the economic transaction costs of obtaining a new card are fairly insignificant for many borrowers, which would lead one to think that consumers would switch cards frequently, there is evidence that psychological switching costs and simple inertia restrict switching rates. One study estimated total switching costs at $150. Moreover, issuers purposefully increase switching costs with loyalty programs.28

Competition is also affected by the availability of information and by borrowers’ ability to process the information needed to comparison-shop. At first glance, it appears that there’s quite a bit of information available, especially through the internet. But it’s not clear how many consumers are actually able to find and process this information. As will be explained in the pages that follow, the credit card product is multidimensional and complex. Comparison shopping between several multidimensional, complex products is a daunting task for many consumers. Finally, the profitability of credit card issuers consistently exceeds the average profitability in the banking industry, leading some commentators to conclude that competition in the credit card market is imperfect. And, allegations of coordinated action have been made against the major issuers.29

In what follows, I largely sidestep the unresolved question about the level of competition among credit card issuers. I show that the central failure in the credit card market—the behavioral market failure—leads to inefficiencies that cannot be cured by even perfect competition. This justifies placing the credit card industry under scrutiny, even if it is subject to intense competition that dissipates any supra-competitive rents.

II. The Credit Card Contract

Credit card pricing patterns are indicative of a behavioral market failure. In this section, we’ll take a look at the relevant features of credit card pricing.30 Then we’ll explore competing rational-choice and behavioral-economics explanations for these pricing schemes.

A. Complexity

The common credit card contract is complex and multidimensional, with numerous fees and interest rates. Credit card fees can be divided into service fees and penalty fees. The service fees include application fees, set-up fees, annual fees, membership fees, participation fees, cash-advance fees, balance-transfer fees, foreign-currency-conversion fees, credit-limit-increase fees, expedited-payment or phone-payment fees, no-activity fees, fees for stop payment requests, fees for statement copies, fees for replacement cards, and wire-transfer fees. And then there are penalty fees, including late fees, over-limit fees, and returned-check (NSF—No Sufficient Funds) fees. According to one industry source, “an average of 9 cardholder fees and costs [are] found in cardholder fee disclosures.”31

Now let’s look at interest rates. In addition to the main, long-term interest rate for purchases, there are introductory (teaser) rates, rates on balances transferred from other cards, rates on cash advances, and default interest rates.32

Most of these fees and interest rates are themselves variable and multidimensional. For example, interest rates are often variable rates that change over time, tracking the movements of a certain index. Introductory rates last for specified time periods, as do default interest rates. Late fees depend (sometimes) on the magnitude of the balance. Etc.33

In addition, the amount a consumer pays in interest depends on the balance that she carries, and these balances are calculated using complex formulas. In the late 1990s, issuers moved from monthly to daily compounding of interest, adding finance charges to the balance each day. This change had the effect of increasing the effective APR by as much as 10 to 20 basis points. Moreover, before the practice was banned by the CARD Act of 2009, issuers used another complex calculation called double-cycle billing. Double-cycle billing effectively eliminated the grace period (the interest-free period that consumers who pay their bill in full receive from the time they make a purchase until the date their payment is due) for consumers who made partial payments the month after making a full payment or who made a partial payment the month following a zero-balance.34

When a cardholder has multiple balances with the same issuer (for example, one for transferred balances, one for cash advanced, and one for regular purchases), the credit card contract specifies how payments will be allocated among the different balances. This payment-allocation method affects total interest payments. Before the practice was banned by the CARD Act of 2009, many issuers allocated payments to low-interest balances first, thus maximizing the finance charges.35 The minimum payment requirement also affects total interest payments, since slower repayment results in more interest paid overall. A cardholder who wants to predict his or her total interest payments faces a daunting task.

With respect to contingent penalty fees and rates, the contingency that triggers the fee or rate needs to be specified. For example, when is a payment considered late—when it arrives on the due date or when it arrives before a certain hour on the due date? What if the due date falls on a weekend or holiday?

When is a default interest rate triggered? In the not so distant past, many credit card contracts included “universal default” clauses, triggering penalty rates based on a host of factors, such as a change in the cardholder’s credit score or a failure to pay a utility bill on time. The CARD Act, while not explicitly banning “universal default,” restricts issuers’ ability to increase rates.36

Many cards also provide a long list of ancillary benefits, including loyalty rewards programs (frequent-flyer miles, cash-back, and the like), rental car insurance, and more. These programs and benefits are themselves quite complex. For example, the program rules detail how miles or points are accumulated, how they can be redeemed, and when they expire if not used. Finally, protection against fraud is of paramount importance to many cardholders. Different issuers offer different mechanisms for protecting their cardholders—another complex benefit.

All these complex details affect the costs and benefits of the credit card product.

B. Deferred Costs

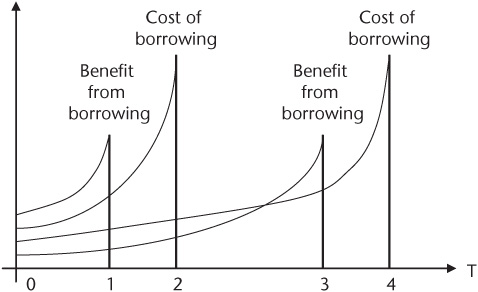

The complex and multidimensional credit card contract provides benefits to consumers while imposing costs on them. These benefits and costs are not randomly distributed across the many dimensions of the contract. Instead, benefits are provided through short-term, more salient dimensions while costs are imposed through long-term, less salient dimensions. With pricing terms, for example, long-term contingent price elements are over-priced while short-term, non-contingent price elements are under-priced. In other words, benefits are accelerated, costs are deferred.

1. Short-Term Benefits

a. No Annual or Per-Transaction Fees

For an issuer, the most straightforward way to cover the fixed costs associated with establishing and maintaining a credit card account would be to charge an annual fee—which is, in fact, what they used to do. Nowadays, however, it is common for issuers to charge no annual fee.37

Similarly, issuers incur the costs of handling the transactions that consumers charge to their credit cards. Yet most credit card pricing does not include any per-transaction fee. In fact, when considering the benefits or rewards programs associated with many credit cards, issuers are setting negative per-transaction fees. The proliferation of membership-rewards programs, frequent-flyer miles, car rental and luggage insurance, discounts on future purchases, and cash-back grants all point to the fact that competitive forces are at play on this dimension of the credit card contract.

Even though they incur positive costs in maintaining credit card accounts and processing transactions, issuers commonly set a zero—or even a negative—price for these services. These observations suggest that issuers are charging below-margin-cost prices on the annual fee and per-transaction fee dimensions of the credit card contract.

But the story is more complex. The preceding account, like the rest of this chapter, focuses on the issuer-consumer contract. This contract sets a low, even negative, price on the per-transaction dimension. A broader analysis would consider also revenue that issuers obtain from merchants, via the interchange fee. (The interchange fee is the percentage—usually 2 percent—that is transferred from the merchant to the issuer on each credit card purchase.) The point is that issuers choose not to charge consumers for the transacting service that the credit card provides. Moreover, while merchants may raise prices to compensate for the “tax” that they pay to issuers, cardholders share the burden of these higher prices with customers using other payment methods.38

b. Teaser Rates

Teaser rates are the low, introductory rates that many credit card issuers offer, typically for a period of six months. After that, a higher long-term interest rate kicks in. Some cards even offer a zero-interest rate during the introductory period. A zero-interest rate on balance transfers is also common.39

Enjoying a low (or no) interest rate is clearly a benefit to consumers, even if this low rate expires after a certain period. Teaser rates also hold the prospect of even greater benefit if consumers transfer their balance to a new card offering a low teaser rate as soon as the introductory period on the current card expires and the post-introductory rate kicks in. The result would be free credit for an indefinite period. While balance transfers—from a card with an expiring teaser rate to a new card with a new teaser rate—do occur, available evidence suggests that they are not as prevalent as one might expect. Rather, substantial borrowing is done at the post-introductory rates. In fact, most borrowing is done at the high post-promotion rates, rather than at the low teaser rates.40

Teaser rates highlight the disparity between credit card interest rates and the underlying cost of funds. Clearly, the cost of funds is greater than zero, yet zero-percent teaser rates are not uncommon. Teaser rates also imply a sharp discontinuous increase at the end of the introductory period. It is difficult to argue that such a rate increase corresponds to changes in the issuer’s cost of funds.

2. Long-Term Costs

a. Long-Term Interest Rates

A central element of credit card pricing is the interest rate charged on credit card debt—the long-term interest rate on purchases that kicks in after the short-term or introductory/teaser interest rate period has expired. (It’s important to note that these interest rates on purchases can be different from the long-term interest rates on transferred balances or cash advances.)

Credit card contracts set high interest rates. The average credit card interest rate was 13.30 percent in 2007 and 12.08 percent in 2008.41 These high interest rates are not surprising. It is natural for unsecured debt, like credit card debt, to carry higher interest rates than secured debt, such as mortgages, home equity lines of credit, and car loans.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, real concern surfaced about the magnitude of credit card interest rates. This concern was based, in large part, on the “stickiness” of these rates—the evidence that credit card interest rates did not track changes in the underlying cost of funds. David Evans and Richard Schmalensee, both Visa consultants, note: “Not only are credit card interest rates high, they do not always move as quickly as other interest rates in response to changes in the cost of the funds that banks raise to support their lending activities.”42

The concern about credit card interest rates has dissipated. Since the late 1990s, competition had begun to focus on the interest rate dimension, driving interest rates down and forcing a stronger correlation with the underlying cost of funds.43

But while the interest rates themselves are becoming more competitive, there is still concern about interest payments. As explained above, interest payments are not only a function of interest rates; they also depend on how balances are calculated, how payments are allocated to different balances, and on the amount of the minimum payment.

Until the CARD Act banned this practice, most issuers calculated balances using the double-cycle billing method. While the main concern with this method is its complexity and opacity, it also generates elevated interest payments in certain circumstances. Similarly, until banned by the CARD Act, issuers commonly allocated cardholders’ payments to the balance bearing the lowest interest rate first. The result was increased overall interest payments.44

The minimum required payment also has a large effect on the overall interest paid by cardholders. Credit card issuers often require only a very small minimum monthly payment, even for large outstanding balances. As long as cardholders do not default, lower monthly payments “increase total revenues by increasing the time it takes to repay the loans and hence the total interest eventually repaid.”45

b. Penalty Fees and Default Interest Rates

Credit card issuers typically collect sizeable fees from consumers who either run late on their monthly payments or exceed the credit limit. Importantly, the magnitude of these penalties is often measured in fixed-dollar amounts—typically around $35—regardless of the degree of deviation from the credit line or tardiness in making the payment.46 Thus, for example, a cardholder might pay a $35 penalty if she misses the due date on a $10 balance by a few days. Hard-pressed to justify such a fee structure, some issuers have begun to offer gradation of late fees, such that smaller fees are imposed for tardiness in paying off a smaller balance.

Paying late or exceeding the credit limit is not a fringe phenomenon. According to a Government Accountability Office study of the six largest issuers 35 percent of accounts were assessed late fees and 13 percent of accounts were assessed over-limit fees. Late fees and over-limit fees are a major source of revenue for credit card issuers, reaching almost $20 billion or approximately 10 percent of total card revenues in 2008. Issuers have also been shortening grace periods to further enhance revenues from penalty fees.47