Covenants

Covenants

1. A covenant is an obligation entered into by deed which affects the use of land for the benefit of another, e.g. someone’s land is not to be used for business purposes.

2. It is an agreement made between the covenantee (who takes the benefit) and the covenantor (who carries the burden).

3. It is governed by the rules of contract as well as the rules of property law:

the contract is enforceable between the original parties, but under the rule of privity of contract a covenant at common law cannot impose burdens upon a third party;

the contract is enforceable between the original parties, but under the rule of privity of contract a covenant at common law cannot impose burdens upon a third party;

the original parties continue to be bound even after they have left the property.

the original parties continue to be bound even after they have left the property.

4. Equity has intervened to allow the burden of covenants to run in limited circumstances.

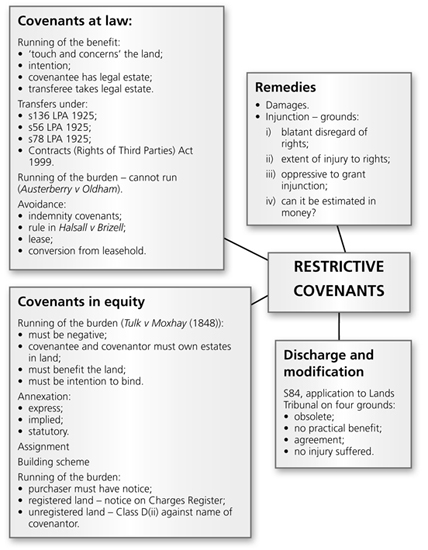

11.2 Covenants at Law

1. Covenants at law can be traced back to the 14th century (Prior‘s Case (1368)). A positive covenant that a prior and his convent would sing all week in the covenantee’s chapel was upheld, notwithstanding the fact that there was no servient tenement to carry the burden.

2. A covenant is enforceable at law even where the covenantor has no estate in law, but the covenantee must have an estate in land that can take the benefit.

11.2.1 The Passing of the Benefit at Law

1. The covenant must ‘touch and concern’ the land – the covenant must be for the benefit of the land and not merely for the personal benefit of the covenantee (P & A Swift Investments v Combined English Stores Group Plc (1989)).

2. There must have been an intention that the benefit should run with the estate owned by the covenantee at the date of the covenant (Smith and Snipes Hall Farm Ltd v River Douglas Catchment Board (1939), presumed under s78 LPA 1925).

4. The transferee of the dominant land must also take a legal estate in that land – any legal estate in land will give the transferee the right to enforce the covenant.

11.2.2 Transferring the Benefit of Covenants at Law

1. A covenant can be expressly assigned under s136 LPA 1925 as a chose in action, but it must be in writing. This is rare as there are other ways of assigning the benefit that are more convenient.

2. S56 LPA 1925 allows the benefit of a covenant to pass to others who, though not mentioned expressly in the conveyance, are expressed to be those for whose benefit the covenant was made, e.g. plots 1–7 are sold and a clause is added in plot 2 to pass the benefit of a covenant to the owner of plot 2, but is worded to cover plots 3–7 as well.

3. S56 does not allow a benefit to be passed to future purchasers.

4. S78 LPA 1925 has been interpreted to be effective to pass the benefit of a covenant to a third party if:

the covenant ‘touches and concerns’ the covenantee’s land;

the covenant ‘touches and concerns’ the covenantee’s land;

the covenant was entered into after 1925;

the covenant was entered into after 1925;

it is only for the benefit of owners for the time being.

it is only for the benefit of owners for the time being.

5. The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 has made extensions to the rights of any third party to covenants entered into after May 2000:

a person who is not a party to the contract can now enforce the contract on his own behalf if either it expressly confers a benefit on him, or the term purports to confer a benefit on him but does not refer to him by name;

a person who is not a party to the contract can now enforce the contract on his own behalf if either it expressly confers a benefit on him, or the term purports to confer a benefit on him but does not refer to him by name;

it cannot be enforced if, on the proper construction of the contract, it appears that the parties did not intend the benefit to be enforceable;

it cannot be enforced if, on the proper construction of the contract, it appears that the parties did not intend the benefit to be enforceable;

the third party must either be named or be referred to generically, e.g. to X (owner of No. 2) and her successors, and the owners of No. 3 and No. 4 (the neighbouring properties). As there is no contrary intention shown then the contract will confer a benefit on the owners of Nos 3 and 4.

the third party must either be named or be referred to generically, e.g. to X (owner of No. 2) and her successors, and the owners of No. 3 and No. 4 (the neighbouring properties). As there is no contrary intention shown then the contract will confer a benefit on the owners of Nos 3 and 4.

11.2.3 Transmission of the Burden at Law

1. Under common law the burden of a covenant cannot run with the freehold land of the covenantor (Austerberry v Oldham Corp (1885)).

2. The rule has been criticised, but was confirmed in Rhone v Stephens (1994): Nourse LJ – ‘the rule is hard to justify’ (Court of Appeal), but Lord Templeman held it to be ‘inappropriate for the courts to overrule the Austerberry case, which has provided the basis for transactions relating to the rights and liabilities of landowners for over 100 years …’ (House of Lords).

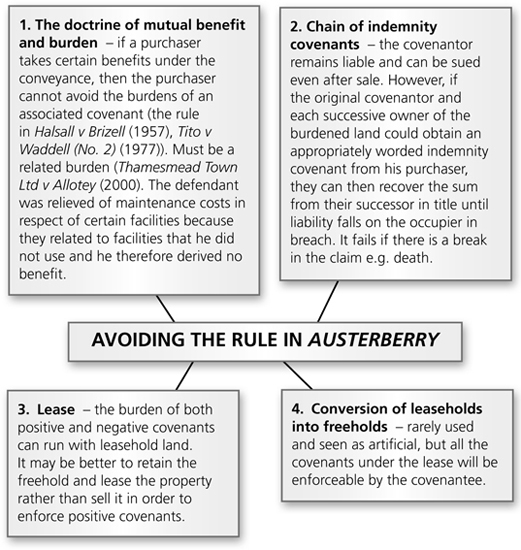

11.2.4 Avoiding the Rule in Austerberry

11.3. Covenants in Equity

11.3.1 The Running of the Burden in Equity

The decision in Tulk v Moxhay (1848).

1. The claimant sold a vacant piece of land in Leicester Square to a purchaser who had notice of a covenant restricting the use of the land (the covenantor agreed to maintain the square as a garden). The purchaser tried to build on the property.

2. It was held that the owners of the neighbouring benefited land had a right in equity to enforce the covenant against the purchaser, because he knew of the covenant when he bought the land and was therefore bound by the covenant.

11.3.2 The Rules Derived from Tulk v Moxhay

1. The covenant must be negative.

A restrictive covenant is a covenant that does not require the expenditure of money.

A restrictive covenant is a covenant that does not require the expenditure of money.

Some covenants appear to be negative but are positive, e.g. not to let the property fall into disrepair is a positive covenant. Maintenance of the property would require expenditure of money.

Some covenants appear to be negative but are positive, e.g. not to let the property fall into disrepair is a positive covenant. Maintenance of the property would require expenditure of money.

2. At the date of the covenant, the covenantee must own the land to be benefited by the covenant, and the covenantor must own an estate to carry the burden (LCC v Allen (1914)).

3. At law, a covenant can pass even where the covenantor has no estate in land, but the right would not pass in equity.

4. The covenant must benefit or accommodate the dominant tenement. This means that it must affect the value of the land and must not be a personal benefit to the owner of the land.

5.