CONTEMPORARY AND FOUNDATIONAL ISSUES IN PUBLIC LAW

Contemporary and foundational issues in public law

1.1 What is a constitution?

1.1.1 A basic definition of a ‘constitution’ would be a body of rules regulating the way in which an organisation or institution operates. However, when the term ‘constitution’ is used in the context of a State’s constitution the definition is a little more complex.

The constitution of a State would be expected to:

- • establish the organs of government. Traditionally, this would consist of a body responsible for legislative functions; a body responsible for executive functions; and a body responsible for judicial functions;

- • allocate power between those institutions;

- • provide for the resolution of disputes on the interpretation of the constitution; and

- • establish procedures etc. for the amendment of the constitution.

1.1.2 The constitution therefore defines the relationship between the various institutions of the State (horizontal relationship) and that between the State and the individual (vertical relationship).

1.1.3 In a narrow sense, a constitution could be defined as a particular document (or series of documents) setting out the framework and principal functions of the organs of government in a particular State. Such a constitution will have, as Wade describes, ‘special legal sanctity’, meaning that it is the highest form of law in the State.

1.1.4 The majority of States have such a constitution, against which all other laws are measured. Should such laws fail to conform to the constitution, they may be declared unconstitutional by the courts.

1.1.5 The United Kingdom does not have a constitution that is the highest form of law since its constitutional principles can be amended by the passing of ordinary legislation – a consequence of the principle known as parliamentary supremacy, or parliamentary sovereignty (discussed in Chapter 3).

1.1.6 For this reason some have argued that the United Kingdom does not have a constitution. However, if we consider the wider definition of a constitution, which would be one that refers to the whole system of government, including all the laws and rules that regulate that government, we can clearly see that the United Kingdom does have a constitution.

1.2 Classifying constitutions

1.2.1 Constitutions can be classified in a number of different ways. We often talk of ‘written’ (codified) or ‘unwritten’ (uncodified) constitutions.

1.2.2 This has been the traditional way of classifying a constitution. In many examples, constitutions are described as being written or unwritten. This is too simplistic an explanation. It is more accurate to describe constitutions as codified or uncodified.

1.2.3 A codified constitution is one where the constitution is enshrined in a single document or series of documents, as, for example, in the United States.

1.2.4 An uncodified constitution is one where the constitutional rules exist, and indeed may be written down in legislation, but there is no one source that can be identified.

1.2.5 The United Kingdom is one of the few major countries in the world not to have a codified constitution. Consequently, the sources of the UK constitution are varied and include, for example, statute, common law and conventions.

1.2.6 In modern constitutional terms the desire to create a codified constitution will often be the result of some significant event, such as, for example:

- • revolution (e.g. France 1789);

- • reconstruction and/or redefinition of a State’s institutions following war/armed conflict (e.g. Germany, Iraq);

- • conferment of independence on a former colony (e.g. India, Australia, Canada);

- • creation of a new State by the union of formerly independent States (e.g. United States, Malaysia);

- • creation of a new State(s) by the break-up of a former Union of States (e.g. States created by the break-up of the former Republic of Yugoslavia).

1.2.7 The United Kingdom has suffered no major historical or political event that has necessitated the creation of a codified constitution. There have nevertheless been significant constitutional events such as, for example:

- • the 1688 Revolution;

- • the Union of England and Scotland (1707) and Great Britain with Ireland (1800);

- • the House of Lords crisis 1910;

- • the abdication of the Monarch 1936; and

- • joining the European Economic Community (now known as the European Union) in 1973.

- • the abdication of the Monarch 1936; and

1.2.8 However, all of these events were responded to or anticipated through parliamentary means; by the passing of ordinary legislation such as, for example:

- • Bill of Rights 1688/9;

- • Parliament Act 1911;

- • Abdication Act 1936; and

- • European Communities Act 1972.

Hence the United Kingdom’s constitution has evolved over time and remains uncodified.

1.2.9 Constitutions can also be classified as ‘rigid’ or ‘flexible’ constitutions. This way of classifying a constitution was first suggested by Lord Bryce in the late 19th century.

- • A flexible constitution is one where all the laws of that constitution may be amended by the ordinary law-making process. The United Kingdom has a flexible constitution.

- • A rigid constitution is one where the laws of that constitution can only be amended by special procedures. Consequently, the constitution is ‘entrenched’. In other words, it is protected from being changed by the need to comply with a special procedure.

1.2.10 F or example, the United States has a rigid constitution that cannot be amended by the passing of an ordinary piece of legislation (an Act of Congress). A special procedure has to be followed, which requires there to be:

- • a two-thirds majority in each House of the Federal Congress (the legislative body), followed by:

- • the acceptance (ratification) of at least three-quarters of the individual states that make up the United States.

A further example: In the Republic of Ireland, a Bill passed by both Houses of Parliament, a majority of votes in a referendum and the assent of the President are required to change the constitution.

1.2.11 A constitution can also be described as a ‘unitary’ or a ‘federal’ constitution. This description rests on the way that law-making bodies or institutions (sometimes known as ‘organs of the state’, ‘state organs’ or simply ‘organs’) are distributed throughout the country as a whole.

- • federal constitution is one where government powers are divided between central (federal) organs and the organs of the individual states/provinces that make up the federation. For example, the United States and Canada have federal constitutions. If there is to be any change in the distribution of power between the federal organs and the state organs, there must be amendment of the constitution using a special procedure.

- • A unitary constitution is one where all government power rests in the hands of one central set of organs.

1.2.12 There are some other ways in which constitutions can be classified. Constitutions can be described as being:

- • Supreme or subordinate – if the legislature cannot change the constitution by itself, then the constitution is supreme. If the legislature can change the constitution by itself, then it is subordinate.

- • Monarchical or republican:

- (a) In a monarchical constitution, the Head of State is a King or Queen and State powers are exercised in their name.

- (b) In a republican constitution, the Head of State is a President.

- (c) This classification has become less popular since the majority of monarchies, including the United Kingdom, have, in practical terms, removed the constitutional power of the Monarch.

- (d) In the United Kingdom, for example, the majority power rests with Parliament and the executive.

- (e) In contrast, in a republican constitution, such as the United States, the Head of State, the President, has significantly more power since he or she is elected and consequently accountable to the people.

- (a) In a monarchical constitution, the Head of State is a King or Queen and State powers are exercised in their name.

- • Fused or separated – the latter is a constitution that adheres to the doctrine of the separation of powers. The former is one that does not, so that certain organs of the State have a range of powers. (The separation of powers is discussed in part of Chapter 2.)

- • De Smith claims that constitutions can also be classified as presidential (e.g. the United States) or parliamentary (e.g. the United Kingdom).

- (a) In a parliamentary system the people choose representatives to form the legislature. The legislature will be responsible for scrutinising the executive and consenting to laws. There is usually a separate Head of State who formally and ceremonially represents the State but who has little political power.

- (b) In a presidential system the leader of the executive, the President, is elected independently of the legislature. The President appoints the rest of the executive, who are often not members of the legislature. The President is also the Head of State.

- (a) In a parliamentary system the people choose representatives to form the legislature. The legislature will be responsible for scrutinising the executive and consenting to laws. There is usually a separate Head of State who formally and ceremonially represents the State but who has little political power.

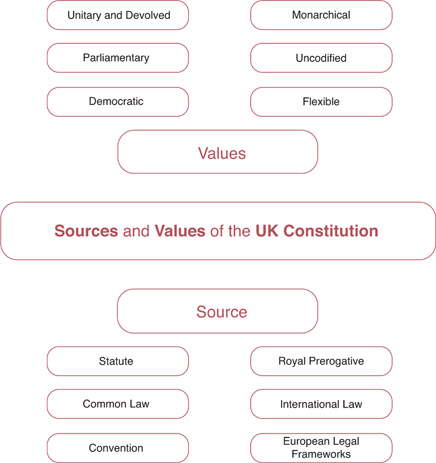

1.3 Essential elements of the UK constitution

The key aspects of the UK’s constitution can be classified as:

1.3.1 Uncodified (or unwritten) – The United Kingdom does not have a codified constitution since there is no single document or series of documents that contain the constitution.

1.3.2 Unitary – The United Kingdom is a union of once separate countries but operates a unitary rather than federal system. The Parliament, sitting at Westminster, has full legislative supremacy but has granted considerable self-government through the process of devolution to:

- • Scotland (e.g. through the Scotland Act 1998);

- • Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland Act 1998); and

- • Wales (Wales Act 1998).

However, the arrangements preserve the unlimited power of Parliament to legislate for the devolved regions and to override laws made by any of the devolved bodies:

- • Numerous matters remain outside the authority of the devolved bodies to legislate on, for example, international relations, defence and national security, and economic and fiscal policies are reserved matters under the Scotland Act 1998.

- • In addition, Parliament retains the authority, or ‘sovereignty’, to repeal these Acts and regain power to fully govern (see Chapter 3) – though politically this might be extremely difficult to achieve, since devolved government in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland is, at the time of writing, very popular.

However, relatively recent modification to this traditional doctrine in the UK constitution with changes to parliamentary supremacy (also known as ‘parliamentary sovereignty’) should be noted.

1.3.4 Monarchical – The Queen is the Head of State and succession to the throne is based on the hereditary principle. However, by convention (see Chapter 4) the Queen exercises her constitutional powers only on the advice of her Ministers and, in many cases, the powers are in fact exercised by Ministers in her name.

1.3.5 P arliamentary supremacy or ‘sovereignty’ – Parliament is supreme (or ‘sovereign’) and can make or unmake any law and legislate on anything it wishes. In theory, no Parliament can be bound by its predecessors or bind its successors. (This principle and the limitations now imposed on it by, e.g., membership of the European Union and the European human rights law system are discussed in detail in Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 respectively.)

1.3.6 Bicameralist – The United Kingdom has a legislative body known as Parliament, which is composed of two chambers. These two chambers are known as the House of Commons (the lower House) and the House of Lords (the upper House).

1.3.7 Democratic – The House of Commons has a membership that is directly elected at least every five years. The political Party that wins the majority of seats in the House makes up the Government.

The leader of that political Party is then appointed by the Queen to be the Prime Minister, who in turn nominates the Ministers of the Government who are responsible for departmental activities and are accountable to Parliament. (The electoral system is discussed in Chapter 9.)

1.4 Should the UK constitution be codified?

1.4.1 The advantages of an uncodified constitution such as that of the United Kingdom include the following:

- • the constitution is flexible and easily adaptable to change; and

- • as Dicey argued, it is a strength that the UK’s constitution is one embedded in the structure of the law as a whole, rather than being merely a piece of paper.

1.4.2 The disadvantages of an uncodified constitution include the following:

- • because of the flexibility of the constitution, constitutional principles can change without the support of the people;

- • the ease with which the constitution can change can lead to confusion and people are left unsure of the constitutional position;

- • the lack of a codified constitution means that many people do not know or understand constitutional principles; and

- • the courts cannot declare Acts of Parliament to be unconstitutional.

1.4.3 Since 1997 the UK’s constitution has undergone the most far-reaching reform since the 19th century. The reforms, whilst not all necessarily completed, could move the United Kingdom away from a traditional unitary state with an unwritten constitution and a sovereign Parliament.

1.4.4 This is partly because the constitution is increasingly being reduced to writing/codified. For example:

- • Lord Bingham identified that 18 statutes of constitutional importance were introduced between 1997 and 2004; and

- • it is possible to identify still more ‘statutes of constitutional importance’ enacted under the Coalition Government between 2010 and 2015.

1.4.5 In addition to this, the doctrine of parliamentary supremacy has been modified by the supremacy of European Community law (see Chapter 6) and the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights by the Human Rights Act 1998 (see Chapter 7). In the context of the effect of membership of the European Union on the supremacy of Parliament, we can see a distinct modification of the traditional doctrine in that implied repeal no longer operates for certain important statutes. These have been called ‘constitutional statutes’ (see 1.6 for further discussion).

1.4.6 The Constitutional Reform Act 2005 provides for moves towards a more formal separation of executive, legislative and judicial powers (see Chapter 2 for the ‘separation of powers’).

1.4.7 Also, the process of devolution for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, whilst not formally affecting the unitary character of the constitution, has created a system that the sovereign Westminster Parliament is unable to undo in practice (see Chapter 3 on parliamentary sovereignty).

- • a codified constitution may be vague, leading to inconsistent interpretation; and

- • a codified constitution will also be reflective of the time in which it was written, and because of its rigidity be difficult to change.

1.4.9 Consequently, in a way similar to uncodified constitutions, the majority of codified constitutions are also supplemented by unwritten standards, rules, practices etc. often to fill any gaps or to allow for adjustment.

1.4.10 Finally, the actual effectiveness of a constitution against abuse of power depends on the willingness of the organs of the State to comply with it, the ability of the courts to enforce it and the people to abide by it, regardless of whether it is codified or uncodified.

1.4.11 In 2007 the Government published a Green Paper entitled ‘The Governance of Britain’. The proposals in the Green Paper included discussion of ideas to:

- • develop a British Bill of Rights; and

- • produce a codified/written constitution.

1.4.12 The idea of a British Bill of Rights was explored further by the Joint Committee on Human Rights and was contained within a Green Paper, ‘Rights and responsibilities: developing our constitutional framework’ published in March 2009. However, no legislation was produced prior to the May 2010 General Election.

1.4.13 But, since the 2010 General Election, the Coalition Government of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats undertook considerable constitutional work involving considerable changes to the landscape of UK governance, though perhaps not drastic constitutional reforms. The General Election of May 2015, however, may mark a serious acceleration of constitutional change in the United Kingdom.

1.4.14 Some of the statutes introduced by the Coalition Government between 2010 and 2015 are addressed at 1.6, on the issue of the concept of constitutional statutes.

1.4.15 The idea of a codified constitution was not expanded upon in either the Constitutional Renewal White Paper published in March 2008, or the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act, which received the Royal Assent on 8 April 2010.