CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS

4.1 Definitions of constitutional conventions

4.1.1 A significant number of important constitutional principles are not found in either statute or common law and are unwritten. They are called conventions.

4.1.2 Many definitions of conventions can be found including, for example:

- • Austin – the ‘positive morality’ of the constitution;

- • Mill – the ‘unwritten maxims’ of the constitution;

- • Freeman – the ‘whole system of political morality’; and

- • Jennings – a source that ‘fleshes out the dry bones of the law’.

4.1.3 Perhaps the most readily useable definition of a constitutional convention is that provided by Makintosh – that such conventions are ‘generally accepted descriptive statements of constitutional and political practice’.

4.1.4 According to Jennings, the existence of a convention may be determined by asking whether there is precedent for the rule; whether those operating under the convention believe themselves obligated to do so; and whether there is a reason for the convention.

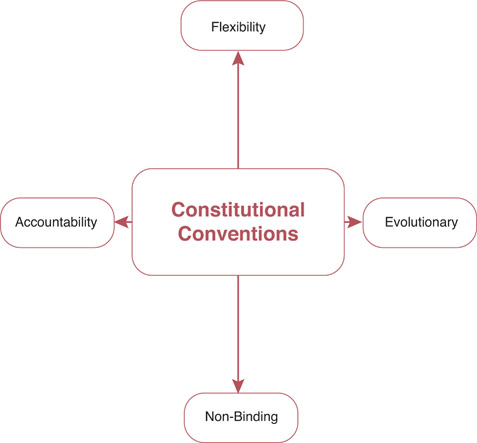

4.1.5 Conventions therefore are often evolutionary and develop through usage. There is no prescribed time or duration required to establish the existence of a convention. This, combined with their unwritten nature, means that it can be very difficult to identify whether a particular convention exists.

4.2 Examples of constitutional conventions

4.2.1 Two prominent examples of a constitutional convention are about the power exercised by the Monarch:

- • the Monarch has the legal right to grant/refuse the Royal Assent; under convention exercises that right on the advice of Ministers; and

- • the Monarch holds the legal right to appoint the Prime Minister, who under convention is the leader of the Party that holds the majority at a General Election and commands the confidence of the Commons.

4.2.2 Two of the most important constitutional conventions, designed to secure executive accountability, are individual and collective ministerial responsibility (see Chapter 10 for details).

4.2.3 Some conventions can be deliberately created, rather than emerging from practice. One example would be the ‘Sewel Convention’, created in 1999, which prevents Parliament from legislating in matters that have been devolved to the Scottish Parliament without obtaining its consent (for detail on devolution see Chapter 8).

4.2.4 Conventions offer the constitution flexibility. The principles provided in the form of conventions often develop because of a desire to avoid formal change through the production of legislation. Hence conventions can be helpful in easing constitutional change in an informal way, for example:

- • from monarchy to parliamentary supremacy – the role of the Monarch in government has effectively disappeared since the 18th century, not as a result of statute, but of conventions. In this way the Prime Minister has also acquired significant Government powers;

- • from Empire to Commonwealth – the recognition of the right to self-rule for the colonies of the Empire was originally reflected in the use of convention, requiring Westminster to seek the approval of such colonies before it could legislate for them.

4.3 Are constitutional conventions legally binding?

4.3.1 The most significant characteristic of constitutional conventions is that they are not legally binding.

4.3.2 Dicey stated that conventions may regulate conduct but ‘are not in reality laws at all since they are not enforced by the courts’;

4.3.3 Marshall and Moodie describe conventions as ‘rules of constitutional behaviour which are considered to be binding by and upon those who operate the constitution but which are not enforced by the law courts’.

4.3.4 However, the courts may recognise the existence of a convention when coming to judgment. For example:

- • Attorney-General v Jonathan Cape Ltd (1976) – where the court recognised the existence of convention, in this case the convention of collective ministerial responsibility, but would not enforce it per se since it was a non-legal rule;

- • Madzimbamuto v Lardner-Burke (1969) – where it was held that no court could declare an Act of Parliament invalid purely because it breached a convention, in this case the convention that Westminster seek the approval of colonies before legislating for them;

- • Manuel v Attorney-General (1983) – where it was confirmed that conventions are non-legal rules and are unable to limit parliamentary supremacy. Consequently any Act of Parliament that breaches convention will nevertheless be upheld by the courts.

4.3.6 The breach of a convention may result in a number of consequences, depending on the importance of the convention itself. Indeed, Dicey stated that the breach of some conventions could result in legal consequences. However, it is rarely the case that breach of a convention will have legal consequences: breaching a convention will most often result in political, not legal, consequences.

4.3.7 Therefore, conventions are generally followed not because of legal consequences but because of political difficulties that may arise otherwise, if they were not followed.