Classification of Trusts and Powers

Chapter 2

Classification of Trusts and Powers

Chapter Contents

What Type of Property Can Be Left on Trust?

This chapter builds upon the meaning and history of equity considered in Chapter 1. The focus now shifts to the single biggest item that equity has created in the English and Welsh legal system: the trust. It is the trust which now remains the subject of the remainder of this book (except for Chapter 17), so its importance to equity cannot be overstated.

As You Read

As you read this chapter, look out for:

what a trust is: its concept, how it grew up from its origins in the Middle Ages to today and the different types of property that can be left on trust;

what a trust is: its concept, how it grew up from its origins in the Middle Ages to today and the different types of property that can be left on trust;

the different types of trust within the two over-arching areas of express trusts and implied trusts; and

the different types of trust within the two over-arching areas of express trusts and implied trusts; and

how a trust can be compared to and distinguished from something that may, at first glance, look very similar to it — a power of appointment.

how a trust can be compared to and distinguished from something that may, at first glance, look very similar to it — a power of appointment.

The Trust

As has been seen in Chapter 1, equity’s history is long. It has grown up over centuries into what it is today: a set of legal principles that contributes meaningfully to the English legal system to mitigate the otherwise harsh effects of the common law. The principles — or maxims — of equity are applied in cases today to give results that are designed to be fair and in good conscience.

But equity is not just a series of maxims that are applied by the courts. Those are only the underlying ideas that guide equity. Equity has more structure to it than the maxims suggest.

As has been mentioned in Chapter 1, equity has also given the legal system a set of bespoke remedies when common law damages are not adequate. Those remedies include orders of specific performance, injunctions and the rectification of documents.1

There is, however, one item that equity has given the legal system which far surpasses all of the other items — remedies or maxims — which it has also provided. That item is the trust. It is the greatest asset that equity has bestowed on the legal system. The word ‘asset’ is not used lightly, for as we shall see, it is the concept of a trust that enables the legal system to recognise more subtle shades of ownership than the common law permits.

Definition

Snell’s Equity defines a trust as being formed when:

a person in whom property is vested (called ‘the trustee’) is compelled in equity to hold the property for the benefit of another person (called ‘the beneficiary’), or for some legally enforceable purposes other than his own.2

This concise definition demonstrates that:

it is equity — not the common law — that recognises the trust;

it is equity — not the common law — that recognises the trust;

due to equity being the body that recognises the trust, the basis of the recognition is likely to be conscience and fairness;

due to equity being the body that recognises the trust, the basis of the recognition is likely to be conscience and fairness;

there are normally three parties to the trust, those being the person who originally owns the property, the trustee and the beneficiary; and

there are normally three parties to the trust, those being the person who originally owns the property, the trustee and the beneficiary; and

there does not, in fact, have to be a human beneficiary to benefit from the trust, since the trustee can hold the trust property for some other ‘legally enforceable purposes’.3, 4

there does not, in fact, have to be a human beneficiary to benefit from the trust, since the trustee can hold the trust property for some other ‘legally enforceable purposes’.3, 4

All of these issues are explored later in this chapter.

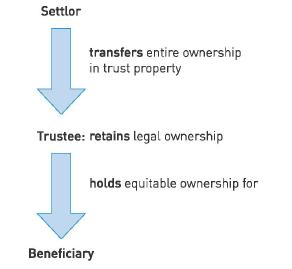

The parties typically involved in the creation of an express trust

In a simple, expressly declared trust, there are three parties involved in the matter. They are:

The settlor. This is the person who creates the trust. He ‘settles’ the property on trust. In order to do this, he transfers the legal ownership of the property to the second person in the arrangement, the trustee.

The settlor. This is the person who creates the trust. He ‘settles’ the property on trust. In order to do this, he transfers the legal ownership of the property to the second person in the arrangement, the trustee.

The trustee. This is the person who administers the trust. The trustee will hold the trust property for the benefit of the third party in the arrangement, the beneficiary. When the trust comes to an end, the trustee must transfer the legal ownership to the beneficiary, but until that time he retains it. Usually it is a good idea to have more than one trustee so that, for example, the burden of trusteeship can be shared. The maximum permitted number of trustees where the trust involves land is four.5

The trustee. This is the person who administers the trust. The trustee will hold the trust property for the benefit of the third party in the arrangement, the beneficiary. When the trust comes to an end, the trustee must transfer the legal ownership to the beneficiary, but until that time he retains it. Usually it is a good idea to have more than one trustee so that, for example, the burden of trusteeship can be shared. The maximum permitted number of trustees where the trust involves land is four.5

The beneficiary. This is the person who benefits from the trust. They will enjoy the equitable interest in the property which is the subject matter of the trust. The beneficiary’s easy task is to reap the rewards of being the person the settlor has chosen to benefit from his gener-osity. As we shall see, however,6 the beneficiary’s harder task is as the enforcer of the trust, making sure the trustee completes his obligations by, if necessary, forcing him to do so. There can be any number of beneficiaries.

The beneficiary. This is the person who benefits from the trust. They will enjoy the equitable interest in the property which is the subject matter of the trust. The beneficiary’s easy task is to reap the rewards of being the person the settlor has chosen to benefit from his gener-osity. As we shall see, however,6 the beneficiary’s harder task is as the enforcer of the trust, making sure the trustee completes his obligations by, if necessary, forcing him to do so. There can be any number of beneficiaries.

The simple trust arrangement can be illustrated by the diagram in Figure 2.1.

Since the trust is a creature recognised by equity, the trustee is obliged to hold the equitable ownership on trust for the beneficiary due to the requirements of fairness and good conscience. By willing to recognise and enforce the trust, equity gives the trustee no other option but to adhere to its terms and will, if necessary, force the trustee to comply with the trust.7

In order to understand those issues, it is essential to have an understanding of how the trust originated.

Where It All Began …

It may have begun like this …

This story of the beginnings of the trust may be real or apocryphal, but it remains a nice tale.

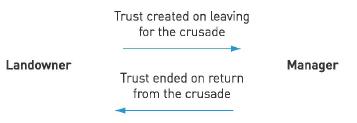

The origins of the trust may be linked to the crusades. The crusades occurred in the time of the Middle Ages and did not just involve English people but also those from other European countries. The crusades were a number of holy wars whose objective was to reclaim the Holy Land around Jerusalem for the benefit of Christians from the Muslims living there.

In all, the crusades led to hundreds of thousands of people, both members of the nobility and those from the lower classes of society, taking up arms to join in the fight for recapturing the Holy Land.

Those crusaders who owned land had a problem. They could — and often would — be away from tending their land for years at a time. What those crusaders needed was someone who could look after their land, manage it and farm it, whilst they were away. Those crusaders did not want to give their land away but instead wanted someone to take temporary custody of it. The land had to be returned to the original landowner on his return from the crusade. The land needed to be given away on a metaphorical piece of elastic, so that its ownership would always bounce back to the original landowner.

The common law, with its blinkered view of matters, could not help the landowner. Even today, if you give something away, the common law sees a change in ownership of the property from you to the recipient. You are no longer the owner at common law. You have given the property away. You have relinquished all claims to it. The common law could not assist the landowner who went away on crusade because the common law was not subtle enough to help with the landowner’s problem. The common law would simply say that the landowner had given his land away to someone else.

Equity, though, with its 3-D glasses, could assist. Equity was capable of looking at the entire situation and seeing that the landowner only wanted to transfer his land to someone else on a time-limited basis. Equity would see that the land was to be, effectively, loaned out and that it was always to be returned to the landowner at the end of the loan period. Equity achieved that outcome through creating and developing the medium of the trust. The landowner would remain the true owner of the land whilst passing the day to day management of the land to someone else whilst he was away on crusade. That manager would then return the land to its rightful owner upon his return. The landowner, it might be said, trusted the manager to look after the land for him during his absence and return it to him on his return. The trust was born.

Note that this crusader’s trust differed from the majority of today’s trusts by only having two parties to it. The manager would take the role of trustee holding the land on trust for the person setting up the trust who was also the beneficiary.

But it probably began like this …

As the victor at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, William the Conqueror had a new prize that he could distribute to his friends and associates who had supported him: England. He began to divide the country up into parcels of land and gave it away to those friends and associates — his chief lords. In turn, those chief lords sub-divided their pieces of land to lords and those lords gave it to other people who did the same until the land found itself being owned by a peasant tenant, at the very end of the chain. Each layer of people made money from it, down to the individual at the bottom of the chain who perhaps farmed the land. This was the concept of feudalism that was established in the early years after the Norman conquest and which grew up over the centuries. The King remained the technical owner of all of the land.

Originally, in return for land being granted from the King to his chief lords and so on, the chief lord would demand services from his lord and each lord from his tenant.

By the beginning of the thirteenth century, actual services being provided by one party to his lord in return for the land were dying out in favour of the tenants paying cash for the privilege of holding their interest in the land. This would enable their immediate successor to purchase any services they actually required. Cash was becoming more and more important in England’s economy.

Related to this concept of each person in the feudal system preferring cash to services was the concept of inheritance. Chattels were not subject to inheritance but land was. The idea of inheritance provided that when a tenant died, the land would pass to his heir. The tenant would not get any choice about this and the concept of the common law recognising a will for a piece of land was anathema.

Death also carried with it another consequence. When the tenant died, privileges became due to the lord or, if it was the chief lord who died, to the King. These privileges were some of the ‘incidents of tenure’. They included:

Customary dues — local customs that were recognised and had to be performed on death. Baker8 gives the example of the ‘custom of heriot’ where the lord could ‘seize the best beast or chattel of a deceased tenant’.

Customary dues — local customs that were recognised and had to be performed on death. Baker8 gives the example of the ‘custom of heriot’ where the lord could ‘seize the best beast or chattel of a deceased tenant’.

The concept of escheat — if the tenant died without leaving an heir, then his land would go to his lord.

The concept of escheat — if the tenant died without leaving an heir, then his land would go to his lord.

Probably since the beginning of time, people have tried to circumvent paying any more than they absolutely must to either the King or to whomever they owe money. Whilst tenants could not find a way around death, what they set out to do was to find a way around the inheritance requirements that their land must go to their heir. That is probably where the concept of the trust first arose.

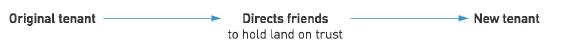

The first use of the trust

The first use of the trust, then, was really to find a way around the rules of inheritance — in other words, to circumvent the requirement that your land had to go to your heir.

It was not possible to make a will of land. The owner of the land had to find some other way to rid himself effectively of his land before he died. If he was able to achieve that objective then, critically, the incidents of tenure applicable on his death would not become due. The tenant would also have some say over who would actually receive his land. This ability to state who should have your land after your death should not be understated and remains a concept of vital importance to most people today.

The key appeared to be that the tenant should take steps to deal with how his land was going to be administered during his life and not wait for the law of inheritance to strike after his death.

The main way that was developed was the concept of the ‘use’.

Glossary: The ‘use’

The ‘use’ has nothing to do with the English verb, to use. It comes from the old French word ‘oeps’. For our purposes, the words ‘use’ and ‘trust’ can be used interchangeably.

A tenant could give the land to his friends on the explicit direction that, after his death, the friends should give the land to whomever the tenant chose. The tenant trusted his friends to honour his instructions hence the concept of the ‘trust’. The concept stopped short of imposing an absolute obligation on the friends that they had to deal with the land as instructed for, if it did this, it would have circumvented the rules on wills too crudely. The arrangement can be represented by Figure 2.3.

This trust reflects the classic tri-partite arrangement described in Snell’s Equity.9

The idea of giving something as serious as a piece of land to someone else on the basis of trust alone was far too flimsy a concept for the common law to recognise. Equity, however, would recognise trusting as a concept since, in the end, it is based on what good conscience should do — good conscience says that if you have been asked to hold a piece of land on behalf of someone else, you should not be allowed to renege on that arrangement. The Court of Chancery, therefore, began to manage trusts and by the 1400s, it consumed much of the court’s time.10

It may have been a bit of both … or something else entirely!

It is not impossible that both the crusades and the wish to avoid inheritance duties both spurred on the development of the trust. The crusades had ended by the closing years of the thirteenth century and we know that, by that stage, the incidents of tenure associated with feudalism were pretty much in full swing. Both crusaders and tenants wanted mechanisms to avoid the common law consequences of what would happen to their land. Both needed to rely on the idea of trusting others to look after their property, which was far too subtle for the common law to appreciate.

Other writers talk about the trust being descended from Franciscan monks who needed property to be held on trust for their benefit but who could not themselves own it due to their vow of poverty.11 In truth, we simply do not know what the facts were which surrounded the creation of the very first trust. Some people like to believe the crusading version of events. History supports the tax evasion version with more facts, but it is by no means impossible that the first trust was used for any version of occurrences.

Split Ownership

The common law was not willing to recognise the concept of a trust. The common law likes definites: someone either owns property or they do not. It had no time for equity’s recognition of ownership of property being based on conscience.

What is left by the two systems running parallel with each other is the concept that it is possible to split ownership of property. As will be seen, this includes all types of property, not just land. At common law, it is possible to have one person owning the property, whilst equity will recognise that the actual benefit of the property is being held for another. Equity does this by saying that the owner has an equitable interest. This is a proprietary interest — an interest in the property which is the subject of the trust — and can be relied upon against the whole world.

Key Learning Point

This is key to understanding a trust. The trust is built upon the basis that ownership of the property is split between the owner of the interest of the property at common law (the trustee) and the owner of the interest in equity (the beneficiary).

Owning the legal interest results in the trustee managing the trust. The equitable interest ensures that the beneficiary can enjoy the fruits of the trustee’s labour.

To try to understand this idea, think of a cream cake. A cream cake consists of cake and fresh cream. Without both cake and fresh cream, the end product is not complete. The trust is like that insofar as it is a mixture of the common law and equity and, without one part, the whole trust is not complete. Yet when looking at a cream cake, it is still possible to identify which part of the object is cake and which part is fresh cream. Depending on your eating preferences, it is possible to separate one from the other. That is true of the trust too: you can identify who owns the property at common law and who owns the property in equity. You can also separate the ownership of the different interests.

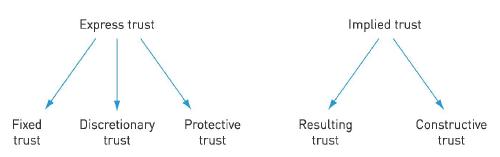

The Different Types of Trust

The expressly created trust is not the only type of trust that is recognised by equity. Figure 2.4 below shows what we might term a ‘family tree’ of trusts.

Each of these must be considered in a little more detail.

Express trusts

The fixed trust

The fixed trust is so called because the interests of the beneficiaries are determined expressly by the settlor when the trust is created. The interests are, therefore, fixed. The trustees must give to each beneficiary what the settlor has expressly provided. So the settlor has deliberately — or expressly — created a trust and fixed the beneficial interests.

If the settlor does not himself define the beneficial shares in a fixed trust, the maxim ‘equity is equality’ applies so that each beneficiary will have an equal equitable share in the trust property.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

Scott appoints Thomas as his trustee and transfers £1,000 to him to hold on trust for the benefit of Ulrika. That is an express, fixed trust. It is an express trust because Scott has deliberately created it and it is fixed because Scott has provided that Ulrika is solely entitled to the benefit of the trust property — the money.

This trust is not confined to having just one beneficiary. For example, suppose another time Scott transfers the same amount to Thomas for Thomas to hold on trust for Ulrika and Vikas in equal shares. That means that Ulrika and Vikas will equally enjoy the trust property. It is still an example of an express, fixed trust because Scott has deliberately created it and the equitable interests are still fixed: Ulrika and Vikas are each to have 50 per cent shares in the money.

The example above demonstrates the classic, three-party arrangement in creating a trust.

There is also another way to declare an express trust, just involving two parties. The settlor can say that he himself is a trustee and declare that he holds certain trust property on trust for the beneficiary. Both ways were recognised as equally good alternatives by Turner LJ in Milroy v Lord.12 There is still the three-party arrangement even in this alternative — it is just that one party is wearing two ‘hats’ of both the settlor and trustee.

Declarations of express trusts can be written down but, if the property of the trust is land, they must be evidenced in writing and signed by a person able to declare the trust.13 If the trust property is not land, it may be surprising to know that express trusts can be declared quite informally, as occurred in Paul v Constance.14

Doreen Paul and Dennis Constance began a relationship in 1967. They moved into the same house and lived together, as a couple, until Dennis died in 1974. In 1969, Dennis was injured at work and he received £950 as compensation for his claim. They both decided to open a bank account to put the money in. The account would only be in Dennis‘ name.

From the time the account was opened to Dennis‘ death, more money was paid into it. A small amount of money was withdrawn from the account for them to buy Christmas presents and food and for them to each treat themselves. By the time Dennis died, the account still had the compensation money of £950 remaining in it.

Dennis had been married prior to meeting Doreen. Dennis died without leaving a will so his widow, Bridget, wound up his estate. Bridget claimed that, as the bank account was in Dennis‘ sole name, the entire contents of it belonged solely to him. That money, she argued, became part of Dennis’ estate which she was bound to administer according to the laws of intestacy, as opposed to any of it belonging to Doreen.

Doreen disagreed. She argued that, whilst the legal title of the money had been in Dennis‘ sole name, a trust had been created by him. That meant that the equitable interest in the money was held by both her and Dennis. Doreen argued that Dennis had declared an express trust of the money. The difficulty that she faced was that the trust had been declared only orally and informally.

The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s finding that there was an express declaration of trust by Dennis in favour of both himself and Doreen. In his judgment, Scarman LJ pointed out that:15

one should consider the various things that were said and done by the [claimant] and the deceased during their time together against their own background and in their own circumstances.

Certain facts led to the conclusion that Dennis had orally declared an express trust. These were that they had only opened the account in Dennis‘ sole name due to their embarrassment of having an account in joint names when they were not married, that they had paid in joint earnings, they had both enjoyed the money that was withdrawn and, crucially, that Dennis had said to Doreen on more than one occasion ‘This money is as much yours as mine’ led to the conclusion that an express trust had been declared.

Scarman LJ emphasised the case was near the borderline. It must be clear when an express trust is formed and it was not entirely clear here: was it, for instance, at the time the bank account was opened or at some later point when Dennis had promised Doreen that the money was theirs to share equally?

But the comments of Scarman LJ quoted above illustrate that equity will look at all the circumstances of each situation to decide if a declaration of an express trust has been made. Equity will not blithely permit informal declarations of trust without considering the full factual surrounding circumstances, as shown by Jones v Lock.16

Robert Jones lived in Pembroke. He went on a business trip to Birmingham and when he returned, he was told off by his child’s nanny for failing to bring a present back for his nine-month old son. His reply was to present the child with a cheque for £900, saying to the nanny: ‘Look you here, I give this to baby; it is for himself, and I am going to put it away for him …’. Robert’s wife then warned him that the child was about to tear the cheque up and his response was to put the cheque in his safe.

The issue for the court to decide was whether Robert’s words and actions were enough to declare a trust.

Lord Cranworth LC held that there was no express declaration of trust because he thought that:

it would be of very dangerous example if loose conversations of this sort, in important transactions of this kind, should have the effect of declarations of trust.17

Again, the court looked at the evidence surrounding the actual words used by the alleged settlor. Lord Cranworth LC thought it highly unlikely that Mr Jones would have considered that he had made a once-and-for-all decision to part with such a large amount of money by such a conversation. This crucial fact surrounding the words spoken by Robert showed that a trust had not been declared.

The case also shows that equity will not use a trust as a ‘second-best’ alternative to save a failed gift. As will be seen in Chapter 7, the general rule is that where a gift fails, a trust cannot step in to rescue it.18

Express fixed trusts can be made easily, but the court will look at all of the evidence surrounding the oral declaration to be confident that a trust truly was intended.

The discretionary trust

This is still a type of express trust since it is deliberately created by the settlor. This time, however, the settlor leaves some issues of choice up to the trustees. The settlor may, for example, give the trustees a choice over who should benefit from the trust (within a defined group) and/or to the extent that those whom the trustees choose should benefit. The settlor might prefer to use a discretionary trust if he cannot himself decide who should benefit from a particular group of people.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

Scott is feeling generous again and appoints Thomas as his trustee and transfers £1,000 to him to hold on trust for the benefit of those people who live in the same road as Scott. Scott provides that Thomas should use his absolute discretion to choose those people who are to benefit and the amounts by which they are to benefit.

This is again a type of express trust since Scott has deliberately created it. The beneficial interests are not fixed. Instead, Scott has said that Thomas must choose who will benefit from a particular group of people and the extent to which they will benefit. This is a discretionary trust. Problems can arise where the settlor fails to define the group with sufficient precision.19

Trustees of a discretionary trust must choose a recipient (or recipients) from the class of people the settlor has defined. The trustees must then consider how much such a recipient should receive from the trust fund.

The rights of people falling into the group as defined by the settlor under a discretionary trust are interesting. They were considered by Walton J in Vestey v IRC (No. 2).20

Walton J said that, individually, such potential recipients had no ‘relevant right whatsoever’ to enjoy any equitable entitlement from the trust. Instead, as a whole, all of the members of the defined group of the trust could join together and collectively enforce a right to ensure the trustees kept to the terms of the trust. The reason for none of the individuals having rights personally under the trust is, of course, because of the very nature of the trust that has been created. The settlor has created a discretionary trust, to benefit a defined group. Any individual within that group may, or may not, eventually be chosen by the trustees to benefit. Until that individual is chosen, he is not a true beneficiary and has no individual rights. Collectively, however, all of those individuals can join together to enforce the trust against the trustees since — by definition — some of them must be chosen from the group. Once an individual is chosen by the trustee to benefit from the trust, he becomes a true beneficiary and only at that point does he have an equitable interest in the trust property. Until that stage, all he has is a hope of being chosen to benefit.21

The protective trust

This is our third type of express trust. As its name suggests, it is an example of equity acting paternalistically again. It seeks to protect beneficiaries from themselves. It ensures that the beneficiary can enjoy the trust property for their lifetime, but if the beneficiary infringes the trust during their life, it is converted into a discretionary trust.22 This can be shown by an example.

EXPLAINING THE LAW EXPLAINING THE LAW |

Scott transfers a house to Thomas, his trustee, to hold on protective trust for Ulrika. Scott is concerned that Ulrika has an alcohol dependency which is out of control, but he wants Ulrika to have a home in which to live. Consequently, Scott makes the trust protective by providing that if Ulrika does not seek treatment for alcoholism, the trust will come to an end and will be replaced with a discretionary trust in favour of other people whom Scott defines.

This trust should give Ulrika the incentive to control her alcohol habit by providing that the trust in her favour will end should she continue to consume it to extremes.