Civil Liability of Security Personnel

4

Civil Liability of Security Personnel

Chapter outline

Classification of Civil Wrongs/Torts

Infliction of Emotional or Mental Distress

Negligence and Security Management

Miscellaneous Issues in Vicarious Liability

Remedies under the Civil Rights Act: 42 U.S.C. §1983

“Private” Applications of §1983

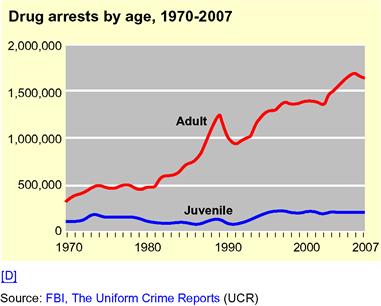

State Regulations as Providing Color of State Law

The Police Moonlighter: A Merging of Public and Private Functions

Introduction

By all accounts, the past four decades have evidenced phenomenal growth of the private security sector.1 In 1972, James S. Kakalik and Sorrel Wildhorn performed a benchmark study for the RAND Corporation,2 which prophetically indicated the influential role security would play in the protection of people and assets. At the same time, the RAND report harshly criticized the security industry, observing:

[T]he vast resources and programs of private security were overshadowed by characterizations of the average security guard—under-screened, under-trained, under-supervised and underpaid and in need of licensing and regulation to upgrade the quality of personnel and services.3

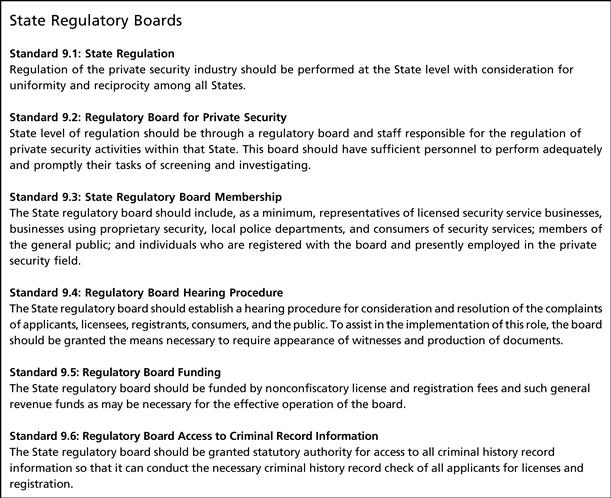

The Bureau of Labor Statistics portrays a bright future for the security industry through 2018. See Figure 4.1.4

Figure 4.1 Security Industry Employment Statistics and Projections through 2018.

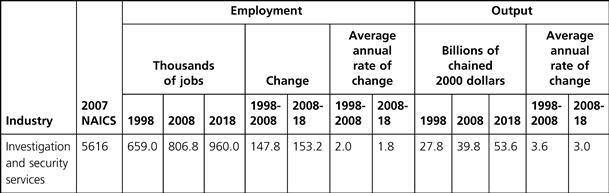

With new and emerging opportunities come the natural liabilities for industry personnel and its employing agencies. This chapter presents an intense analysis of the civil realm and its corresponding liabilities, as applied to private sector justice. The industry knows how liability impacts the bottom line better than any other constituency. The Risk and Insurance Management Society, Inc., lists the issues of risk in the marketplace at Figure 4.2.5

Visit the risk and insurance management society and discover its many resources at http://www.rims.org/Pages/Default.aspx.

Figure 4.2 Issues of Risk in the Marketplace.

The Hallcrest Report II corroborates this picture escalating liability:

Perhaps the largest indirect cost of economic crime has been the increase in civil litigation and damage awards over the past 20 years. This litigation usually claims inadequate or improperly used security to protect customers, employees, tenants, and the public from crimes and injuries. Most often these cases involve inadequate security at apartments and condominiums; shopping malls, convenience and other retail stores; hotel, motels and restaurants; health care and educational institutional; office buildings; and the premises of other business or governmental facilities. Frequently, private security companies are named as defendants in such cases because they incur 2 basic types of liability: (1) negligence on the part of the security company or its employees and (2) criminal acts committed by the security company or its employees.6

Private sector justice is deep in the mix of things, places, and circumstances where liability problems are most likely to occur. In retail and parking complexes, in government buildings and nuclear facilities, the industry will be exposed to liability just because of how and where it carries out its responsibilities. Other locales where liability is part of the territory include the following:

• Shopping malls, convenience stores, and other retailers

• Hotels, motels, casinos, bars, and restaurants

• Health care and educational institutions

• Security service and equipment companies

• Transportation operators such as common carriers, airports, and rail and bus stations

• Governmental and privately owned office buildings and parking lots

Add to this striking growth in employment the trend toward privatization itself,8 and it is only logical that accentuated levels of responsibility and legal liability are part of the security industry landscape. With increased functionaries laboring in the private sector, there will be a corresponding increase in legal liability. The Hallcrest Report II sees nothing but continuous employment growth for private sector justice:

Total private security employment is expected to increase to 1.9 million by the decade’s end. The present rate of change in employment from 1980 to 2000 is approximately 193%. The annual rate of growth in employment is anticipated to be about 2.3%, roughly double the rate of employment growth for the national workforce. By 2000 there will be 7 private security workers for each group of 1,000 Americans, an increase of 1 from 1990. Further, by 2000 there will be about 13 private security employees for each group of 1,000 workers in the nation—also an increase of 1 employee from the 1990 figure.9

The National Center for Policy Analysis (NCPA) foretells a further expansion of private justice function. Since the mid-1960s, the economic impact of private sector justice has been significant by any measure, as the NCPA notes:

• And the private sector on occasion has been used innovatively in other ways to prepare cases for district attorneys, to prosecute criminal cases, and to employ prisoners behind bars.10

Increased functional responsibility begets enhanced civil liability. “Because the effects of liability cases are far reaching, potentially affecting all levels … the more security personnel know about their responsibilities and exposure to liability, the less chance the company will be crippled with lawsuits.”11 Given the range and diversity of services private security implements, including “a whole spectrum of concerns, such as emergency evacuation plans, security procedures, bomb threats, liaisons with law enforcement agencies, electronic security systems, and the selection, training and deployment of personnel within institutions,”12 liability is an ongoing policy issue. Dennis Walters, in his article “Training—The Key to Avoiding Liability,” notes:

In the United States, where lawyers occupy a significant portion of the professional class, it is important to keep track of emerging legal trends when you are developing a comprehensive security training program. It is very helpful to know what forms of legal action are appearing that will affect the security industry.13

In fact, liability concerns are by nature part of the security game. The functions of the industry are now simply part of the mainstream of American life.14 Stephen C. George highlights how liability is part and parcel of crowd control:

Many professional security firms refuse to handle events that draw large crowds. They are often the best people equipped to deal with such situations, but they reject these jobs because of the concern over—and the potential for—liability. But if private security won’t work these events, and police are reluctant to act, who’s left to do the job?15

Whether crowd supervision and control or security at defense installations, the industry’s growth cannot escape the downside of an emerging economic force—that of legal liability. With the industry’s tentacles around every place imaginable, private sector justice will have to discover how to mitigate and prevent liability.

This chapter’s discussion involves the civil liability of security personnel from various angles. First, exactly what is the definition of civil liability and what types of civil liability are there? Second, what is negligence? How does negligence impact the security workplace? Third, what are torts, especially the intentional variety? How can the industry be held strictly accountable? Finally, what ameliorative steps can be taken to minimize the diverse forms of civil liability?

The Nature of Civil Liability

Civil wrongs or causes of action can be grounded in various remedies including negligence, intentional torts, and even strict liability findings. Private sector justice is exposed each and every day to both its protections and its corresponding liability. Consider this factual situation:

Mr. X and his fiancée Ms. Z were shopping in a large department store in the State of Missouri. The evidence indicated that Mr. X left the department store without purchasing a tool. Soon after, Mr. X was confronted by a security officer in a hostile fashion. Mr. X was handcuffed after engaging in a physical altercation with the security guard. Mr. X’s face was bleeding, his ribs were bruised and he suffered other injuries. Mr. X was eventually acquitted at trial on all charges brought forth by the department store.16

Who bears legal responsibility for these physical injuries? Is the liability civil and/or criminal in scope? Has there been an assault or battery? Was the restraint and confinement of the suspected shoplifter reasonable? Has there been a violation of Mr. X’s constitutional or civil rights? How are civil actions distinguishable from criminal actions when reflecting on this situation?17 At its core, a civil liability arises from an action that causes a particular and demonstrable harm. Civil wrongs, like criminal actions, have consequences. Civil wrongs harm personally and cause measurable damages. A civil harm is a cause of action that is uniquely personal. An individual who is victimized by an unsafe driver is personally victimized. Civil rights are correctly construed as individual harms, whereas criminal acts are seen as a public harm, an action against the society as a whole that injures the public peace or public good. Crimes, despite their personal harm, do more to influence the common psyche of a neighborhood or family. A criminal act injures the world at large. While criminal law is chiefly concerned with protection of society and a restoration of the public good, the basic policy behind tort law is “to compensate the victim for his loss, to deter future conduct of a similar nature, and to express society’s disapproval of the conduct in question.”18 Civil remedies are more concerned with making injured parties economically and physically whole, whereas criminal remedies are more preoccupied with just desserts—namely punishment of the perpetrator either by fines or incarceration. Tort remedies involve damages, whereas criminal penalties result in incarceration or fines.19

Intentional conduct that causes civil harm is generally defined as a “tort.” These are some of the more common torts:

Each cause of action requires a proof of its elements. “When a party has alleged facts that cover every element of the cause of action, the party has stated a prima facie case.”20

While there is much that distinguishes civil and criminal actions, “the same conduct by a defendant may give rise to both criminal and tort liability.”21 Selection of either remedy does not exclude the other, and in fact, success in the civil arena is generally more plausible since the burden of proof is less rigorous. Remember the evidentiary burden for the proof of a crime requires proof beyond a reasonable doubt. A successful civil action merely mandates proof by a preponderance of the evidence or by clear and convincing evidence.

The fact pattern portrayed here gives rise to a series of civil actions:

1. Assault:

2. Battery:

• An act which confines a plaintiff completely within fixed boundaries

• Plaintiff was conscious of his own confinement or was harmed by it

4. Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress:

• An act that is extremely outrageous

• Intention to cause severe emotional distress

• Actual emotional distress is suffered

Tortious conduct can be costly. Damages determined by a jurist or a jury can be economically devastating. It is difficult to get an exact figure on how many corporate dollars are lost through jury judgments against security personnel and their employers, but the fact that those losses are substantial is indicated by the circumstances of the legal climate as it affects security today. For example, jury awards in the past often amounted to only a few thousand dollars in many cases. Today, awards of $100,000 or more are becoming increasingly common.

To get some insight into the size and scope of jury awards, search the well-regarded Verdict Search at http://www.verdictsearch.com/index.jsp.

Various industry authorities estimate that at least one suit involving security is filed in the United States every day.23 A review of the literature indicates that cumulative damage awards are consistently increasing.24

In sum, there are both similarities and differences between civil law and criminal law. Table 4.1 provides a concise overview.

Table 4.1 Comparison between Crimes and Torts

| Torts or Civil Wrongs | Crimes |

| Personal harm | Harm against society |

| Does not require intentional behavior | Generally requires intentional behavior |

| Requires proof by a preponderance of evidence | Proof beyond a reasonable doubt |

| Selection of civil remedy does not exclude a criminal prosecution | Selection of criminal prosecution does not exclude a civil remedy |

| Results in damage awards generally compensatory and sometimes punitive in nature | Results in fines, imprisonments, and orders of restitution |

Classification of Civil Wrongs/Torts

Security agencies and personnel need to become accustomed to the common civil actions that firms and their officers will likely encounter. Internal and external policies of security firms and the defensibility of its practices and procedures need constant evaluation to prevent litigation.

Torts are further divided into three main classifications:

A review of common civil wrongs that regularly influence and affect security practice follows, along with illustrative case examples.

Intentional Torts

Intentional torts imply an understanding or willingness to act or cause a specific end. Intentional acts are not driven by carelessness, accident, or mistake, but a clear intentionality. In civil law, the specificity and clarity of mind and intent is less rigid than the criminal counterpart, although proof of intent remains a fundamental element. Criminal law insists on more intentionality with terms like “premeditation,” “willfully,” and “purposely.” In assessing criminal behavior, the law requires that the person choose consciously to perform a certain act and not be under duress, coercion, or suffering from any other impediment that influences volition.

Civil intent partially mirrors criminal intent. “Evil motive or the desire to cause injury need not be the end goal; intent to cause the actual result is sufficient.”26 In the law of torts, intention can be strictly “without malice or desire to harm but with full knowledge to a substantial certainty that harm would follow.”27 Specific examples of intentional torts commonly applicable in security settings are highlighted in this chapter.

Assault

Since security personnel commonly deal with situations requiring detention and restraint, the potential for assault is not unexpected. An analysis of assault requires proof of the following elements:

Noticeably absent from this element list is an absolute requirement of offensive contact or actual touching. In most jurisdictions, an assault is considered to be an incomplete battery. Instead, the act of touching is in its threatened stage, symbolized by its tentativeness and lack of execution. Movement or an act of the defendant toward a prospective victim may consist only of eye movement or a slight jerk of the body. The plaintiff must reasonably anticipate, believe, or have knowledge that this potential action against the body is harmful. The proposed injury is imminent, immediate, or without any significant delay. Consider this factual scenario:

One evening in February 1976, George I. Kelley entered a Safeway store in southeast Washington, D.C. to shop for groceries. He noticed that an automatic exit door was not working properly and that it was necessary to exert pressure on the door to push it open. According to Kelley’s testimony, he completed his shopping and later advised the cashier that he wanted to make a complaint about the broken door. The cashier suggested that Kelley talk to the Assistant Manager, Mr. Wheeler. When Kelley did so, the Assistant Manager responded that the door would be fixed in two to three months and that Kelley was always making trouble for him. Kelley testified that he had never made a complaint to Mr. Wheeler before that night and also stated that the Assistant Manager said to him “boy, if you don’t get out of this store I’m going to have you arrested.” Kelley responded, “Well call the Police, I want to file a complaint.” Holding his bag of groceries, Kelley stood in front of the store to await the police. The Assistant Manager beckoned to a Security Guard, Larry Moore, who was assigned to the store by Seaboard Security Systems, Ltd. At the same time, the Assistant Manager asked someone in the back of the store to call the police. Within a few minutes, Officer Knowles of the Metropolitan Police Department arrived. According to Kelley, Knowles first spoke to the Assistant Manager, who called him over and then approached Kelley and said “the Manager wants you to leave the store.” Kelley testified that he was about to respond to the Officer when the Security Guard approached from the rear, and grabbed him around the throat. Simultaneously, the Police Officer stuck his knee into Kelley’s chest. The two pushed him to the ground and handcuffed him. Without any resistance from Kelley, the Officer and the Security Guard took Kelley to the back of the store where he stood in handcuffs in view of store customers. After ten or fifteen minutes, a police car arrived and transported him to the precinct where the police charged him with unlawful entry.28

Using the elements of an assault or a battery action, does the plaintiff have a reasonable basis for filing a claim against Safeway and its employees? Clearly, a harmful or offensive contact took place, but was there a reasonable apprehension of harm? In upholding the assault and battery determination the court held:

Kelley alleges that although he offered no resistance, the Seaboard Guard grabbed him from behind, around the throat and pushed him to the ground before handcuffing him. Although witnesses were present each told different versions of the events. We find there was sufficient evidence upon which a jury could properly have found Safeway liable for assault and battery. Accordingly we affirm the jury finding liability on that account.29

The plaintiff’s claim of assault was correctly struck down when the sole basis for the tort was a 45-minute detention, in a state with merchant privilege, says Josey v. Filene’s.30 Even the assaults of third parties, bystanders, onlookers, and intermediaries are a security liability according to Charles Sennewald, founder and former president of the International Association of Professional Security Consultants. Sennewald highlights the pressing realty:

Before stores were sued primarily for what they did. Now they are held accountable for acts of third parties against customers, such as muggings or purse snatchings in a store’s parking lot.

This trend requires consultants to assess whether a store provides a reasonable level of security for invitees.

No matter the trends, the more enlightened retail security executives see the need for periodic outside objective advice. Firms that have failed to stay current, by not tapping into available consulting resources, have the most to lose. And some do!31

Battery

Closely aligned to assault is the battery action. A battery requires an actual touching or offensive contact to another person without right, privilege, or justification. Proof of a battery requires a demonstration of the following:

• The intention to cause the contact or to possess knowledge of the consequences

• Actual physical impairment, pain, or illness to the body

• Conduct that is personally offensive based on reasonable standards

• Causation between the defendant’s act and the actual injury to the plaintiff

The primary concern in battery analysis is whether the touching or contact is offensive. While the term “offensive” possesses a certain amount of relativity, most courts have held that offensive does not mean “that the contact must be violent or painful.”32 Offensive contact can be touching, tapping, poking, spitting, and even indecent gestures. Given the constant interaction with customers in retail settings, battery is a predictable reality for security firms.33 Security professionals should weigh and evaluate restraint techniques and detention policies, and use of force regimens as they carry out their many responsibilities, always acting in a preventive way and anticipating potential liability problems. Clients and suspects will shape those policies. For example, the suspected shoplifter should be treated with far more restraint than the suspected rapist. Reflect further on the delicate balance that must be maintained between a proprietor’s right to protect his or her property interest and the right of a consumer not to be accused, confronted, or accosted without substantial cause. Creative legal minds easily conjure up a battery case under diverse factual scenarios, “since it is not necessary that the defendant intend to cause specific harmful injury, only that the contact itself was intended.”34 In the area of retail security, such as detention of a shoplifter, any security action has a battery prospect. Security specialists often walk the fine line of professional restraint and excessive force. Courts look to the totality of circumstances when assessing the difference.35

False Imprisonment

To prove a prima facie case of false imprisonment, the following elements need demonstration:

• An act that completely confines a plaintiff within fixed boundaries

• Defendant is responsible for or the cause of the confinement

• Plaintiff or victim was conscious, aware, and knowledgeable of the confinement or was harmed by it

Industrial and retail settings provide fertile grounds for cases of false imprisonment. Evaluate the following facts:

A United Security Guard detained the Plaintiff as she was leaving the store and accused her of taking a gold necklace which she was wearing around her neck. The Plaintiff responded that the necklace had been given to her by her parents. The Guard escorted her to the Assistant Manager’s Office and told the Assistant Manager that she had witnessed the Plaintiff taking the necklace. The Plaintiff again stated that the necklace was a gift from her parents and expressed a desire to leave so that she could contact her Mother who was waiting in the parking lot outside. After the guard procured the necklace, the Assistant Manager accompanied the Plaintiff outside the store to meet her Mother. The latter confirmed the Plaintiff’s story as to where the necklace had come from, and all three proceeded back to the store office. There, the Security Guard produced a release form which she said would have to be signed. The Mother refused, and the Assistant Manager informed her that the store’s policy was not to prosecute minors. The Mother replied that she intended to prosecute the store whereupon the necklace was returned to her and both the Plaintiff and her Mother were allowed to leave. The Plaintiff also introduced evidence showing that the store did not stock necklaces of the same quality as the one the Plaintiff was wearing when she was detained.36

While there may be room for disagreement about the intentions of the security personnel, a close review of the facts reveals fulfillment of this tort’s fundamental elements. First, the plaintiff was confined to a specifically fixed boundary. Second, it was the intention of the defendant to confine that party. Third, the defendant was clearly responsible for causing the confinement. Lastly, the plaintiff was conscious of it and, in her view, was harmed by it.

It is only natural that false imprisonment cases arise in the retail environment. Even good faith efforts to restrain suspected shoplifters are subject to mistakes. As a result, proprietors have been granted, in select jurisdictions, immunity in the erroneous detention of suspected shoplifters under merchant privilege laws. Merchant privilege laws usually provide that

[w]henever the owner or operator of a mercantile establishment … detains, arrests, or causes to be detained or arrested any person reasonably thought to be engaged in shoplifting and, as a result … the person so detained or arrested brings an action for false arrest or false imprisonment … no recovery shall be had by the plaintiff in such action where it is established by competent evidence: (1) That the plaintiff had so conducted himself or behaved in such manner as to cause a man of reasonable prudence to believe that the plaintiff, at or immediately prior to the time of the detention or arrest, was committing the offense of shoplifting … or (2) That the manner of the detention or arrest and the length of time during which such plaintiff was detained was under all the circumstances reasonable.37

Read the federal case at http://ftp.resource.org/courts.gov/c/F3/413/413.F3d.175.04-2251.html, and explain why the court concluded that the merchant privilege defense, while relevant, was not essential to a jury finding.

Though there is some variance in merchant privilege laws, most state laws adhere to a formula that blends the presumption of detention with a right of the merchant to protect his or her goods and services.38 A typical construction might be as follows:

(c) PRESUMPTIONS—Any person intentionally concealing unpurchased property of any store or other mercantile establishment, either on the premises or outside the premises of such store, shall be prima facie presumed to have so concealed such property with the intention of depriving the merchant of the possession, use or benefit of such merchandise without paying the full retail value thereof within the meaning of subsection (a), and the finding of such unpurchased property concealed, upon the person or among the belongings of such person, shall be prima facie evidence of intentional concealment, and, if such person conceals, or causes to be concealed, such unpurchased property, upon the person or among the belongings of another, such fact shall also be prima facie evidence of intentional concealment on the part of the person so concealing such property.

(d) Detention—A peace officer, merchant or merchant’s employee or an agent under contract with a merchant, who has probable cause to believe that retail theft has occurred or is occurring on or about a store or other retail mercantile establishment and who has probable cause to believe that a specific person has committed or is committing the retail theft may detain the suspect in a reasonable manner for a reasonable time on or off the premises for all or any of the following purposes: to require the suspect to identify himself, to verify such identification, to determine whether such suspect has in his possession unpurchased merchandise taken from the mercantile establishment and, if so, to recover such merchandise, to inform a peace officer, or to institute criminal proceedings against the suspect. Such detention shall not impose civil or criminal liability upon the peace officer, merchant, employee or agent so detaining.39

Use of language like “reasonableness,” “prudence,” and “honest belief” manifests the legislative desire to assure protection from illegitimate claims of false imprisonment. Judgments for false imprisonment are not granted unless the plaintiff shows evidence of willful conduct, maliciousness, or wanton disregard.40 Appellate courts commonly apply the standard of “reasonableness” in determining civil liability. A Wisconsin case, Johnson v. K-Mart Enterprises, Inc., 41 dismissed an action for false imprisonment after evaluating the total duration of imprisonment consisting of 20 minutes. The gentlemanly demeanor and behavior exhibited by the retail store’s security personnel, coupled with a polite and formal apology given upon verification of the facts, favorably impressed the court:

The Appellate Court concurred in the dismissal noting that Wisconsin has a statute protecting merchants from liability where they have probable cause for believing that a person has shoplifted. Under the statute a merchant may detain such a suspect in a reasonable manner and for a reasonable length of time. The Court held that the K-Mart security guard did have probable cause to detain Johnson.42

While the facts thus enunciated arguably prove the elements, security professionals should be aware that professionalism and courtesy during detention influence judicial reaction. A case in point is Robinson v. Wieboldt Store, Inc., 43 whose facts are summarized here:

On November 21, 1977, at about 6:30 p.m., the 66-year-old Plaintiff was shopping at the Evanston Wieboldt Store. She purchased a scarf … with her credit card. Plaintiff chose to wear the scarf, removed the price tag, and handed it to the sales clerk. The sales clerk did not object when Plaintiff put the scarf around her neck. The clerk handed Plaintiff a copy of the sales receipt, which Plaintiff put in her pocket. The Plaintiff then took the escalator to the 3rd floor of the store. As Plaintiff stepped off the escalator a security guard grabbed her by the left arm near her shoulder. The guard gave his name and showed his badge. He asked her where she got the scarf and requested her to accompany him to a certain room. She told him she purchased the scarf on the 1st floor and had the receipt in her pocket. During the entire confrontation the guard was holding tightly onto Plaintiff’s upper arm. Plaintiff, who was black, described the guard as white, weighing about 200 pounds, having dark hair and wearing a dark brown suit. The guard grabbed the receipt from the Plaintiff’s hand, continued to hold her upper arm, and Plaintiff struggled to get the receipt back from the guard. Plaintiff testified that she felt very sick, as if her head was blown off and her chest was sinking in. She said she was frightened and that it seemed that the incident lasted forever. The guard took Plaintiff down to the scarf department on the 1st floor. Plaintiff removed the scarf from her neck and noticed a small tag on the corner. This tag gave instructions on the care of the scarf. This was apparently what the security guard had seen before grabbing the Plaintiff. The sales clerk told the guard the Plaintiff had purchased the scarf a short time earlier. The guard told the sales clerk that she had caused Plaintiff a lot of trouble and had embarrassed her. He then walked away without apologizing to the Plaintiff.44

By the guard’s actions, the plaintiff, for a period of time, was confined to a fixed boundary. Developing a restriction of this sort was the security agent’s intention. The cause of the confinement can only be attributed to the security guard. Since the plaintiff was conscious of the confinement and certainly felt harmed by it, a prima facie case has legal support. Not surprisingly, the defendant security officer and the employing firm relied on the statutory defense of a merchant privilege.45 Given the facts of Robinson v. Wieboldt,46 can a trier of fact conclude that the security official acted reasonably in this case? Were the actions of the security guard, especially in terms of the force exerted, reasonable in light of the age and stature of the plaintiff? The court held:

A review of the record reveals Plaintiff’s assertions do in fact present a case of false imprisonment. She testified that the security guard grabbed her tightly on her upper arm while they were on the 3rd floor of Defendant’s store, restricting her freedom of motion. Even after presenting the guard with a sales receipt she was forced to travel to the 1st floor of the store further restricting her liberty and freedom of locomotion. To claim that Plaintiff could have refused to go to the 1st floor and unilaterally ended the confrontation ignores the realities of the situation.47

False imprisonment cases can arise from distinct and differing contexts. For example, in a claim based on civil rights violations, the test is “objective reasonableness” of the security officer’s conduct during that detention. The “reasonableness of an officer’s conduct comes into play both ‘as an element of the officer’s defense’ and ‘as an element of the plaintiff’s case.’”48 For this reason, many courts have struggled with the application of qualified immunity.

Review the facts of Lynch v. Hunter Safeguard: 49

Defendant Donald Hunter, a ShopRite security guard, followed Plaintiff out of the store to her car, stopped her, took her keys and refund authorizations, and then escorted her back into the supermarket. Hunter then took Plaintiff to a storage room, restrained her wrists in handcuffs … and fastened the handcuffs to a metal stairway. The handcuffs were so tight that they cut Plaintiff’s skin, numbed her hands and fingers, and caused them to swell and darken. Plaintiff begged Hunter to allow her to use a bathroom . … She finally lost control and urinated on herself. Hunter laughed and then photographed Plaintiff in her wet clothing. Plaintiff repeatedly asked Hunter to allow her to telephone her 69-year-old mother. … Hunter ignored Plaintiff’s requests. Plaintiff remained shackled to the stairway for three to four hours. … Hunter directed other ShopRite employees to search Plaintiff’s pocketbook … [and] Plaintiff’s car … two ShopRite managers, supported and encouraged Hunter’s actions. “For a considerable length of time, neither Defendants … telephoned the police or told anyone else to telephone the police about Plaintiff’s detention, handcuffing or the shoplifting accusation against her.”

“Someone from the store” eventually telephoned the Philadelphia Police Department, and Officers … responded to the call … Officer John Doe III immediately ordered Hunter to remove the handcuffs. Hunter … told the two police officers that Plaintiff had shoplifted items from the supermarket, and asked them to arrest her. … Officers John Doe III and Jones-Mahoney placed Plaintiff under arrest. …

At the police station, Plaintiff was placed in a “small, filthy, insect-infested cell with five other women, four of whom would not allow Plaintiff to sit down on a bench for several hours. Repeatedly, Plaintiff was inappropriately touched by one of these women.” Plaintiff was incarcerated for twelve hours. … She was not allowed to telephone her mother and “was not able to drink from the water fountain. …” After seven hours, she was given food. Plaintiff was charged with Retail Theft … but the charge was later dropped.50

In this case, the debate on false imprisonment is easily resolved after a cursory review of the security methods employed. It is likely that the conditions of the detention itself would elicit juror sympathy.

The security industry is paying dearly in false imprisonment cases. Here are a few illustrations:

• A retail customer was awarded $20,850 in damages in a false imprisonment case. The security manager refused to listen to the customer’s explanation.51

• An award of $30,000 in punitive damages as well as $20,000 in compensatory damages was the result of a false imprisonment case upheld after the trier believed security personnel were loud, rude, and unpleasant.52

• A customer was detained for over two hours in a security office and was searched and questioned, even though he had a receipt, which accounted for every item in his possession. Judgment for $85,867.85 plus costs was upheld.53

The method of detention weighs heavily on the court when reaching legal conclusions about false imprisonment. Detention is scrutinized and adjudged in light of many factors:

1. If physical force itself is used to cause the restraint;

2. If a threat of force was used to effect the restraining;

3. If the conduct of the retail employee reasonably implied that force would be used to prevent the suspect from leaving the store.54

All of these liabilities could have been avoided with sound security policies. As Leo F. Hannon suggests in his article “Whose Rights Prevail?,” “The bottom line seems to be that you can’t beat common sense.”55

Security professionals should design a system of detention and restraint that does not trigger, by its shortcomings, a false imprisonment action. For example, to confine does not require walls, locks, or other barriers. Since confinement can be the result of an emotional coercion or threat, establish a polite, cordial environment when detaining. Confinement is defensible if performed by an official that is legally empowered to act. While some protection is afforded in jurisdictions that have merchant privilege statutes, any action taken by private security personnel without that limited privilege will be subject to a false imprisonment claim. Other security professionals urge regularity and professionalism as the preventive steps to thwart off liability suits based on false imprisonment. John Francis’ The Complete Security Officer’s Manual corroborates this suggestion:

A security officer is expected to be businesslike, alert, and helpful. He should treat people as he would like to be treated. He will more than likely be asked the same questions numerous times. He should remember the person standing in front of him is asking the question for the first time. He will be bombarded with questions all during his shift, and he must realize the people asking these questions have their own personal pride and they are certainly not going to ask for information that is otherwise easily obtainable to them. An officer should be sure when a person approaches him that he attempts to help them. If he cannot help them, because it is against facility rules/regulations, that should be explained. At least leave them with the knowledge that an attempt was made to help them. A simple word or a phrase: “Let me see if I can help you. Here are the rules and they cannot be changed. You will have to check with the person in charge, or call this number to get the assistance you need.” Rather than saying, “This can’t be done, it’s against the rules, and you’re not going to do it.” Rudeness is no help to a person who needs help. An officer must be courteous. There is a saying that if, “courtesy is contagious, rudeness is epidemic.” Security officers are expected to be courteous to people every day. By being rude to one employee in a facility, the word is spread throughout the facility that all the security officers are rude and inconsiderate.56

Even job announcements for positions in the private sector stress professionalism and appropriate demeanor. Examine the Guardian Security Announcement at http://www.guardiansecurityinc.com/employment/job.asp.

In contract guard settings, particularly when the company employing the security service defends itself as an independent contractor, the falsely imprisoned will argue liability on behalf of both the agent and the principal if the latter ratifies the former’s conduct. “The liability of a principal for a wrongful restraint or detention by an agent or employee depends on whether the act was authorized or subsequently ratified, or whether the act was within the scope of the agent’s or employee’s employment or authority.”57

Infliction of Emotional or Mental Distress

Often coupled with claims of assault, battery, and false imprisonment is the claim of intentional or negligent infliction of emotional or mental distress. Mental distress is the psychic portion of an injury—the pain and suffering portion of a calculable claim. Since only the minority of jurisdictions recognizes the negligent aspects of this tort, no further consideration will be given.58 Most American jurisdictions do recognize the tort of intentional infliction of mental distress.59 Many require that the tort be strictly parasitic in nature—that is, a cause of action resting uon another tort that causes actual physical injury or harm, like assault and battery. Critics of the cause of action have long felt that without an actual physical injury that can be objectively measured, mental and emotional damages are too speculative to quantify. That position has now become a minority view since most jurisdictions recognize, or at least give some credence to, the soft sciences of psychiatry and psychology in matters of damage.

For the security industry, the individual consumer, employee, or other party who is accosted, humiliated, or embarrassed by false imprisonment, battery, or assault will often attempt to collect damages tied to the emotional strain of the event. However, in an effort to provide quality control to mental damages, the elements of this tort are rather rigorous. Consider its basic elements:

• The act is deemed extreme or outrageous.

• The intention is to cause another severe emotional distress.

• The plaintiff actually suffers severe emotional distress.

The general consensus regarding extreme and outrageous conduct is that it is behavior that the ordinary person deems outrageous. The borders of extreme and outrageous behavior encompass harsh insults, threats, handcuffing, physical abuse, and humiliation.60

At best, the term “emotional distress” is a series of “disagreeable states of mind that fall under the labels of fright, horror, grief, shame, humiliation, embarrassment, worry, etc.”61 The behavior complained of must be so extreme and outrageous as “to be regarded as atrocious, and utterly intolerable in a civilized community.”62 Furthermore, the emotional distress allegedly suffered must be serious.63 A mere insult or petty bickering does not qualify.

The private security employee’s very position may make seemingly innocent conduct outrageous or extreme.64 The issue of emotional damages came to the forefront in Montgomery Ward v. Garza.65 In assessing the damages of a plaintiff in a false imprisonment case, the court considered testimony by the plaintiff that he was embarrassed and humiliated:

His son testified that Garza seemed confused, embarrassed, and frightened. He withdrew from his friends and he changed his eating habits after the incident. A psychiatrist testified that Garza was incapable of overcoming the emotional impact resulting from the false arrest, that Garza’s epileptic condition could be aggravated by the event and that psychiatric treatment would be desirable. Garza’s personal physician testified that Garza suffered from acute anxiety and depression and stated that he suffered an increased number of epileptic convulsions since his detention. The doctor has had to increase his medication and to add another tranquilizer in an effort to control Garza’s attacks. Based on this evidence the Court found that the award of $50,000.00 was “not so excessive that it shocks our sense of justice and the verdict was therefore affirmed.”66

In an age when psychiatric objectification is readily accepted and the judicial process welcomes the expert testimony of psychologists, it is not surprising that the bulk of tort actions seek emotional damages. The best preventive medicine that security professionals can ingest is to be certain, regardless of the innocence or guilt of the suspect, not to create conditions that could be characterized or described as extreme or outrageous. Just as public police must maintain an aura of decorum and professionalism, it is imperative that private justice personnel minimize the influence of emotion in daily activities. They must treat suspects with the utmost courtesy and handle cases and investigate facts with dispassionate insight and objectivity.67

For a brief summary of case law, see Louisiana State University’s web link at http://biotech.law.lsu.edu/courses/tortsf01/iiem.htm.

Malicious Prosecution

An unjustified claim or charge of criminal conduct or the affirmative use of the justice system to unlawfully prosecute may give rise to a claim of malicious prosecution. Accusations of criminality should never be made lightly, since the ramifications can be costly in both a legal and economic sense. This tort includes the following elements:

• The initiation of legal proceedings

• Legal proceedings terminate or result in favor of the accused

Proof that a charge lacked a reasonable basis in fact or in law, was lacking in probable cause, or was prompted by actual malice are the central issues in malicious prosecution. Probable cause, in a sense, is a defense to a claim of malicious prosecution for its finding imputes good faith in the action or a basis which justifies the action. To say that something has probable cause means minimally that it is arguable. And while its finding does not imply certainty, it is sure enough to justify the action. Probable cause deals with probabilities not rigorous, scientific certitude. Probable cause conclusions verify the merit of any underlying cause of action.68

More challenging in proving a malicious prosecution is the showing of malice. Malice is the willful and intentional design to harm another.69 Malice implies an improper motive—namely, that the initiation of legal action has little to do with a plaintiff’s desire to bring the accused or the defendant to justice. Instead, the accused is unduly harassed by the improper filing of civil and criminal actions and victimized by the very processes that have been established to ensure justice. Instead of justice, spite, ill will, politics, hatred, or other malevolent motive govern the decision to sue. In Owens v. Kroeger Co.,70 a jury awarded $18,500 in damages in a malicious prosecution action when Mr. Owens was prosecuted for shoplifting 99 cents worth of potatoes. The exoneration, coupled with the aggressive prosecution of Mr. Owens, convinced the trial jury that malice was the retailer’s sole motive. The trial judge disagreed and overturned the jury’s finding. Some jurisdictions, such as Georgia, bar an action for malicious prosecution even when the defendant is subsequently declared innocent if a probable cause basis triggered the arrest. In Arnold v. Eckerd Drugs of Georgia, Inc.,71 a store customer was detained and prosecuted for shoplifting based on probable cause. The court’s decision noted:

With regard to appellant’s claim for malicious prosecution, “[t]he overriding question … is not whether [she] was guilty, but whether [appellee] had reasonable cause to so believe—whether the circumstances were such as to create in the mind a reasonable belief that there was probable cause for the prosecution.” We have held that, under the undisputed evidence, appellee’s agent had reasonable grounds to believe appellant to be guilty of shoplifting at the time of her arrest. Appellant produced no evidence that, subsequent to her arrest, appellee acquired further information tending to show that its earlier assessment of the existence of probable cause was erroneous.72

In Butler v. Rio Rancho Public School,73 the U.S. District Court reiterated the need to prove the defendant’s motivations, especially when the defendant misuses legal processes to accomplish illegal and unlawful ends.

Defamation

The cumulative effect of false imprisonment, intentional infliction of mental distress, assault and battery, and other related torts in security detention and restraint situations often leads to the tort of defamation. Defamation requires proof of the following elements:

• Defamatory statement by a defendant

• Statement concerns of the plaintiff

• Demonstration of actual damages

When private security personnel make the accusation that “you have stolen an article” or “you are under suspicion for shoplifting,” the potential for a defamation case exists.74 An accusation of any criminal behavior may suffice. However, the defamatory remark must be “a statement of fact which in the eyes of at least a substantial and respectable minority of people would tend to harm the reputation of another by lowering him or her in the estimation of those people or by deterring them from associating with him or her.”75 If a security professional makes no accusation, at least in terms of verbal comment, or couches his or her interchange with the client in neutral, investigative jargon, few problems will arise. Again, common sense demands that security personnel be courteous and noncommittal and that they investigate all the facts necessary to come to an intelligent conclusion concerning the events in question.

Defamation is not mere insult or “casual insults or epithets … because such actions are not regarded as being sufficiently harmful to warrant invocation of the law’s processes.”76

Another issue in the proof of a defamation action relates to the statement’s verity. No action in defamation can be upheld if the statement, in fact, is true, and the defendant cannot demonstrate falsehood. The fact that a statement has been made is, of course, important. To whom the statement has been made is also a legal consideration, for the statement must be published or announced to others to be actionable. This is called the requirement of publication.77 “Thus a derogatory statement made by a Defendant solely to the Plaintiff is not actionable unless someone else reads or overhears it.”78 Since many retail and industrial situations involving security personnel are in the public eye, it behooves security practitioners, when they make a claim, to do so discretely. Making accusations at the cash register or in other public settings is not intelligent discretion. Security personnel must be sensitive to the public nature of defamatory remarks. Beyond public comment, the tort arises from published comments or the dissemination of written material. “Preparation of and distribution of a letter to a personnel file and to other officers may constitute publication sufficient to support cause of action [for defamation].”79

An affirmative defense regarding defamation involves the proof of truth or falsity of the assertion. Truth defends the defamation as announced in Nevin v. Citibank 80 when a security guard alleged “‘a black female was making large purchases with a Citibank Visa card’ and that, ‘she makes purchases, she puts the merchandise in her vehicle and returns to the store.’”81 Since these facts were true, the cause of action was dismissed.

Invasion of Privacy

Since much of the activity of private security is clandestine and investigatory in nature, the tortious conduct involving invasion of privacy can sometimes occur. Corporate spying—the practice of using security firms to monitor employee conduct—manifests the fine line between invading privacy and conducting a legitimate investigative tactic. Alleged spying on prospective union organizers illustrates this tension. A Chicago firm enlisted to surveil union organizers “violated Illinois’ privacy law by gathering information on employees’ opinion about unions as well as such seemingly unrelated details as where a worker shopped, an employee’s off-duty fishing plans, and a female worker’s living arrangement.”82 The case elucidates the fine line between a privacy violation and legitimate corporate oversight. The use of such spies is widespread in American business and especially common among retailers with razor-thin profit margins: “Employee theft accounted for an estimated $11 billion of the $27 billion in shortages reported by U.S. retailers in 1992. … Drug abuse is the other major reason for covert investigations.”83 These sorts of economic pressures on the profit margin prompt extraordinary measures.

The legal concept of invasion of privacy as an actionable civil remedy is a recent legal phenomenon spurred on by modern concerns for civil and constitutional rights.84 Also supporting this legal remedy are recent efforts “expressed in federal and state statutes, in proposed legislation, and in judicial decisions.”85 The private justice sector’s use of investigative technology and intrusive methodologies and practices further supports this legal remedy. When reviewing information gathering and investigative practices, security professionals should keep a few points in mind:

Do not permit security personnel to use force or verbal intimidation or abuse in investigations of employees and customers; collect and disclose personal information only to the extent necessary; inform the subjects of disclosures to the greatest extent possible; avoid the use of pretext interviews; avoid the use of advanced technology surveillance devices whenever possible; know the standards adhered to by the consumer reporting agencies and other parties with whom you exchange personal information; train your employees in privacy safeguards; periodically review your information practices with appropriate personnel and counsel.86

There are four distinct types of the invasion of privacy:

• Invasion of privacy—Intrusion

1. An act which intrudes into someone’s private affairs

2. The action is highly offensive to a reasonably prudent person

• Invasion of privacy—Appropriation

• Invasion of privacy—Public Disclosure of Private Facts

2. Concerning the private life of a plaintiff

3. Which is highly offensive to a reasonably prudent person.

• Invasion of privacy—False Light

Each of these types targets conduct that is an affront to public sensibility and personal integrity. In other words, to what extent or extremes can a party go to gain access to information or divulge the same? For example, how far can a media critic or newspaper reporter go when divulging the secret lives of the rich and famous? Are there not some activities that are uniquely personal and beyond the rabid publicity of a media without checks and balances? When, at least in this crazed age, does a public disclosure of a private fact in a private life offend individual and collective sensibilities? Politicians often complain about the intrusive stories concerning their sexual dalliances. Proponents of the disclosure hold that any public figure is fair game, as are that person’s personal, moral, and sexual habits. Critics say that these disclosures are offensive to the average person.

For an excellent summation of invasion of privacy and corresponding case law, visit http://www.cas.okstate.edu/jb/faculty/senat/jb3163/privacytorts.html.

A recent American Law Reports annotation, “Investigations and Surveillance, Shadowing and Trailing, as a Violation to the Right to Privacy,”87 addresses this very topic. Recognizing the increased use of private detective agencies and other investigatory boards, the annotation states:

Those instances in which the surveillance, shadowing or trailing is conducted in an unreasonable and obtrusive manner, intent on disturbing the sensibility of the ordinary person, without hypersensitive reactions, is usually held … an actual invasion of the right to privacy.88

In the business of security, there are many private actions that become publicly disclosed. In divorce proceedings, private sector investigators delve into highly charged conduct that touches privacy:

Where the surveillance, shadowing and trailing is conducted in a reasonable manner, it has been held that owing to the social utility of exposing fraudulent claims, because of the fact that some sort of investigation is necessary to uncover fictitious injuries, an unobtrusive investigation, even though inadvertently made apparent to the person being investigated, does not constitute an actual invasion of his privacy.89

Drug screening, testing, and related monitoring programs have been challenged on privacy grounds. For the most part, private sector businesses and other entities are largely free to conduct such tests. The American Management Association recently reported that 63 percent of companies surveyed do test for drugs. Some 96 percent will not hire individuals who test positive. SmithKline Beecham Clinical Laboratories reports that 11 percent of 1.9 million people tested produced a positive test. This figure reflects a four-year decline in applicant test-positives.

Reid Psychological Systems continues to see increasing applicant drug use. In a study of more than 17,000 applicants in four major industries, 12 percent admitted to drug use on a written questionnaire.90 Pinkerton Security and Investigation Services, Inc., and Environmental Narcotics Detection Service (ENDS) have instituted a partnership, whose singular purpose is to screen accurately and efficiently report drug testing results. ENDS helps employers detect traces of illegal drugs in the workplace. Pinkerton Security and Investigation Services collects test samples, and the Woburn, Massachusetts-based Thermedics analyzes them. Clients receive results within 48 hours.91

Both alcohol abuse and drug abuse in the workplace remain a substantial problem. The Bureau of Justice Statistics paints a distressing picture of workforce drug usage. A study that focused on findings from the 1994 and 1997 National Household Survey of Drug Abuse reported:

• 70 percent of illicit drug users, age 18 to 49, were employed full-time.

• 1.6 million of full-time workers were illicit drug users.

• 1.6 million of these full-time workers were both illicit drug and heavy alcohol users in the past.92

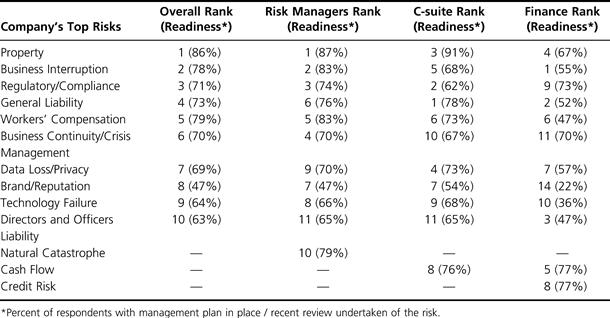

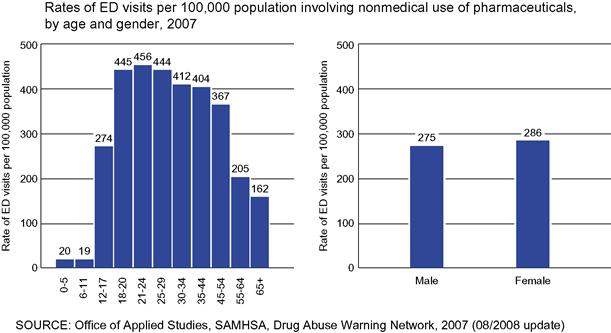

The picture is further edified by simply looking at data on arrests for drug crimes, displayed in Figure 4.3,93 which presents a most unfortunate upward incline that shows no sign of abating.94 Even emergency room data reflect this grim reality (see Figure 4.4).95

Figure 4.3 Drug Arrests by Age.

Figure 4.4 Rates of Emergency Room visits from the use of drugs.

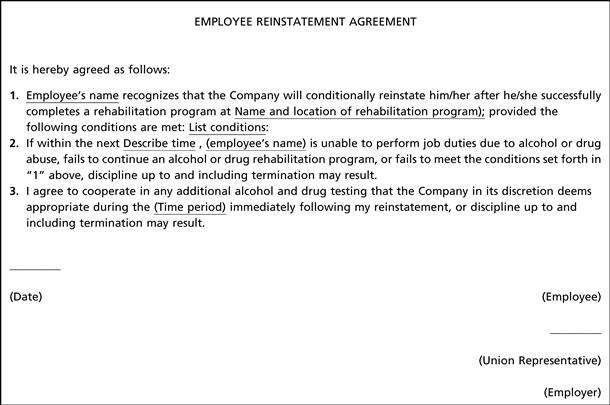

While most courts uphold the right to conduct such tests, any condemnation that does occur usually relates to the reliability of the methodology employed and the fairness relating to the test itself. Privacy questions need be balanced with the negative impact, the social and human costs that drugs cause in the workplace. Most American businesses allow a first offense, and upon individual rehabilitation will reinstate the employee. See the agreement at Figure 4.5. If employees complain about activities that invade their privacy, formally document their statement. See Figure 4.6.

Figure 4.5 Employee Reinstatement Agreement.

Figure 4.6 Employee Privacy Complaint.

Evaluate the fact patterns that follow to discern whether or not an arguable invasion of privacy has taken place: