Challenges Based on Breach of Natural Justice

CHALLENGES BASED ON BREACH OF NATURAL JUSTICE

(1) Summary of Challenges Based on Breach of Natural Justice | |

(1) Summary of Challenges Based on Breach of Natural Justice

10.01 The following points of general application have emerged from the cases on natural justice:

1. An adjudicator is required to act impartially under s. 108(2)(e) of the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’), and under the common law. A party has the right to present its case before an impartial tribunal where justice must be seen to be done.

2. An adjudicator must conduct proceedings in accordance with the rules of natural justice, or as fairly as the time constraints permit. However the speed with which adjudications are conducted means that some breaches of natural justice which have no demonstrable consequences may be disregarded.

3. The adjudicator’s conduct is key, and this may in some cases require asking whether the adjudicator himself considered he had sufficient time to conduct proceedings fairly. If he considers that justice cannot be done then he may request an extension of time or, if necessary, resign.

4. Parties can, by their conduct, agree to waive or acquiesce in a breach of natural justice. If so, a subsequent challenge to enforcement proceedings is unlikely to be successful.

(2) General Principles of Natural Justice

10.02 Section 108(2)(e) of the 1996 Act imposes a duty of impartiality upon the adjudicator. Where an adjudication is being conducted under the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’), this duty to act impartially is also imposed by paragraph 12.

10.03 In addition, the common law principles of natural justice require that those affected by decision-makers are dealt with in a fair manner. The House of Lords have said, in another context, that quite what ‘fairness’ requires will depend on the character of the decision-making body, the questions it is being asked to answer and the framework (statutory or otherwise) in which it is operating.1 In the most general terms, natural justice requires that a party should have the right to prior notice of the case against it and a fair opportunity to make representations before a decision is made; the specific requirements will depend on the circumstances of each particular case.2

10.04 Absent agreement of the parties, adjudication under the Act is subject to strict time limits. That necessarily limits the time for preparation and presentation of evidence and argument and subsequent consideration by the adjudicator. Questions of unfairness in the course of adjudication therefore need to be considered against that background. An adjudicator is required to conduct proceedings in accordance with broad concepts of procedural fairness.3 Thus whilst the adjudicator must be impartial and allow the parties an opportunity to present their cases, the nature of the process will introduce limitations as to what is required. As observed in Discain Project Services Ltd v Opecprime Development Ltd (2000) BLR 402,4 adjudication is inherently an imperfect but not necessarily final process5 which makes regard for the rules of natural justice ‘more rather than less important’, particularly where there is no appeal on fact or law from the adjudicator’s decision.

10.05 There is therefore something of a balancing act to be performed. It is now well established that adjudicators must conduct proceedings ‘in accordance with natural justice, or as fairly as the limitations imposed by Parliament permit’.6 However, the speed of adjudication makes it inevitable that natural justice might sometimes be compromised. Indeed, the courts have recognized that adjudication is ‘not a finely tuned instrument’ but rather a ‘summary and at times blunt instrument for the resolution of disputes’.7

10.06 Thus, the principles of procedural fairness (or the need to observe the rules of natural justice) are not to be regarded as diluted for the purposes of the adjudication process, but are judged in the light of time restraints, the provisional nature of the decision, and any concessions or agreements made by the parties as to the nature of the process in a particular case.8

Materiality of Breach

10.07 Not every breach of natural justice necessarily leads to an invalidation of the decision.9 The breach must be a material breach, which will be a question of fact and degree in each case. The courts will ask whether the issue at the heart of the natural justice objection had any ‘demonstrable consequence’ and if not, ‘repugnant’ as it may be, such breaches are disregarded.10 Thus, an unsuccessful party must not merely assert a breach of natural justice, ‘any breach proved must be substantial and relevant’.11

10.08 Guidance for applying the test of materiality was provided in Cantillon Ltd v Urvasco Ltd (2008).12 In that case, the adjudicator awarded prolongation costs for a nine-week period; however this was a different period from that claimed in the dispute referred to him. Urvasco sought to resist enforcement on the grounds that it had not been given an opportunity to address the adjudicator on the prolongation costs which applied to this alternative period, even though the contending periods had clearly been discussed during the adjudication. In refusing the challenge, Akenhead J made the following points:

57. … (a) It must first be established that the Adjudicator failed to apply the rules of natural justice;

(b) Any breach of the rules must be more than peripheral; they must be material breaches;

(c) Breaches of the rules will be material in cases where the adjudicator has failed to bring to the attention of the parties a point or issue which they ought to be given the opportunity to comment upon if it is one which is either decisive or of considerable potential importance to the outcome of the resolution of the dispute and is not peripheral or irrelevant.

(d) Whether the issue is decisive or of considerable potential importance or is peripheral or irrelevant obviously involves a question of degree which must be assessed by any judge in a case such as this.

10.09 Provided that the procedure is fair, then the rules of natural justice cannot be used to protect a party against an outcome that may be considered unfair. As discussed in Chapter 7, adjudication decisions may be enforced even where they contain manifest errors of fact or law as long as they were made within the adjudicator’s jurisdiction. Considerations of natural justice, therefore, concern whether the process has been conducted fairly. They are not concerned with the question of whether the adjudicator got the decision wrong unless it is alleged that was the result of a breach of natural justice in the way the procedure was conducted. However, the terms of the decision are often relied upon to support a challenge based on breach of natural justice.

Adjudicators’ Decisions Should Generally Be Enforced

10.10 Parties cannot treat every perceived procedural unfairness as grounds for challenging enforcement. The observations of Chadwick LJ in Carillion Construction Ltd v Devonport Royal Dockyard Ltd (2005) (Key Case)13 apply equally to challenges based on natural justice as challenges based on excess jurisdiction:

1. It is only too easy in a complex case for a party dissatisfied with the decision of an adjudicator to comb through the adjudicator’s reasons and identify points upon which to present a challenge under the labels ‘excess of jurisdiction’ or ‘breach of natural justice’.

2. The objective behind the 1996 Act requires the courts to respect and to enforce an adjudicator’s decision unless it is plain that the manner in which it was reached was obviously unfair.

10.11 The need to have the ‘right’ answer has been subordinated to the need to have an answer quickly, and, as the cases discussed below show, it will only be in the clearest of circumstances that enforcement of a decision may be resisted on these grounds. As the Court of Appeal affirmed in AMEC Capital Projects Ltd v Whitefriars City Estates Ltd (2004),14 allegations of breach of natural justice are ‘easy enough’ to make, however only those challenges based on a ‘properly arguable objection’ should be allowed to succeed:

22. It is easy enough to make challenges of breach of natural justice against an adjudicator. The purpose of the scheme of the 1996 Act is now well known. It is to provide a speedy mechanism for settling disputes in construction contracts on a provisional interim basis, and requiring the decisions of adjudicators to be enforced pending final determination of disputes by arbitration, litigation or agreement. The intention of Parliament to achieve this purpose will be undermined if allegations of breach of natural justice are not examined critically when they are raised by parties who are seeking to avoid complying with adjudicators’ decisions.

The Adjudicator’s Conduct Is Key

10.12 The manner in which the adjudicator has conducted himself in order to perform the balancing act between natural justice and tight time constraints is the prime consideration. In particular, a Court will ask whether he has complied with the adjudication process established by the parties’ agreement or the Act and/or the Scheme. The case law confirms that adjudicators must apply natural justice principles ‘without fear or favour’ and that it is the adjudicator’s conduct of the adjudication which is key, rather than the action of the parties:

31. … The introduction of systems of adjudication has undoubtedly brought many benefits to the construction industry in this country, but at a price. The price, which Parliament, and to a large extent the industry, has considered justified, is that the procedure adopted in the interests of speed is inevitably somewhat rough and ready and carries with it the risk of significant injustice. That risk can be minimised by adjudicators maintaining a firm grasp upon the principles of natural justice and applying them without fear or favour. The risk is increased if attempts are made to explore the boundaries of the proper scope and function of adjudication with a view to commercial advantage.15

Impact of the Human Rights Act 1998

10.13 Early discussions after the 1996 Act came into force considered whether the process of adjudication would stand up to the scrutiny of the Human Rights Act 1998 (‘the Human Rights Act’). The Human Rights Act reflects the rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (‘the Convention’) including Article 6(1) of the Convention whereby, in the determination of its civil rights and obligations, a party is entitled to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal with public announcement of the judgment.

10.14 In 2001, the TCC confirmed in Elanay Contracts Ltd v The Vestry (2001)16 that the Convention did not apply to adjudications, which were ‘not in any sense a final determination’, but could be reopened. This decision was criticized by the commentators in the Building Law Reports but was quickly followed by the case of Austin Hall Building Ltd v Buckland Securities Ltd (2001).17 Despite approaching ‘the matter from a different direction’, Judge Bowsher concluded that the process of adjudication could not be described as legal proceedings by a public authority (and thus caught by the Convention and the Human Rights Act) as adjudications were designed to avoid the need for legal proceedings.18

10.15 No further challenge to the inherent fairness of the adjudication procedure based on the Convention or the Human Rights Act has been made since 2001. Accordingly, whilst the adjudication procedure might be considered by some to be inherently unfair, an adjudicator is bound by the time limits that parliament prescribed19 and there is no legal right to a public hearing or public pronouncement of an adjudicator’s decision. On the contrary, adjudication is generally approached as though it is a confidential process.20

(3) Possible Grounds for a Natural Justice Challenge

Inadequate Time or Opportunity to Respond

10.16 Absent agreed extension of time, in an adjudication under the Act the adjudicator’s decision must be reached within 28 days of the referral of the dispute. Even with agreed extensions of time adjudication is a rapid procedure by comparison with litigation or arbitration. Parties have sought to use the rapid nature of adjudication as the basis for resisting enforcement of a decision by asserting that the dispute referred was simply too complex for adjudication, that it had insufficient time to respond to the referral, or that it had insufficient time to deal with specific material, particularly where such material was provided late in the timetable.

Dispute Too Complex

10.17 In London & Amsterdam Properties Ltd v Waterman Partnership Ltd (2003) (Key Case)21 there was a suggestion (obiter) that there may be some disputes, in particular final-account disputes, that may be too complex to be decided fairly in the time limits imposed by adjudication. A similar comment was made in AWG Construction Services Ltd v Rockingham Motor Speedway Ltd (2004).22 That argument has subsequently been raised by parties seeking to resist enforcement—but without success to date.

10.18 The Act does not impose any restriction on the scale of dispute that may be referred to adjudication23 and it provides a mechanism for extension of time either by the referring party or by agreement between the parties (such extensions therefore being reliant, at least, on the cooperation of the referring party). There is no power for the adjudicator to extend time unilaterally. However, the courts have made clear the approach that should be taken by adjudicators: if the adjudicator considers that the dispute is too complex to allow a fair procedure and decision within the time limits, then the parties should be invited to agree an extension of time, failing which the adjudicator should resign.24 The courts have taken the view that the adjudicator is best placed to make the assessment as to whether there is sufficient time for submissions by the parties and consideration by the adjudicator. If it can be shown that the adjudicator properly considered whether a fair decision could be reached in the time allowed, then such challenges are unlikely to succeed. That is likely to be discernable from the adjudicator’s reaction to requests for more time during the adjudication. Absent such contemporaneous requests, protestations after the event that there was insufficient time will lack credibility.

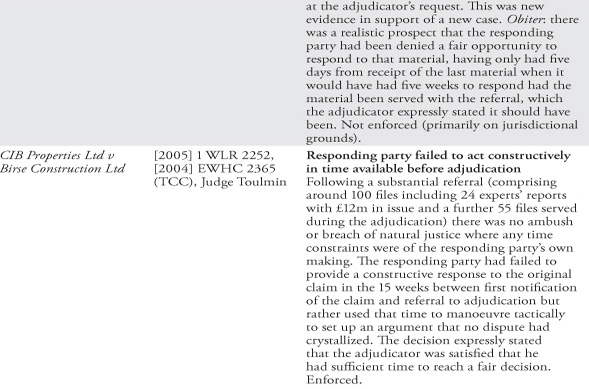

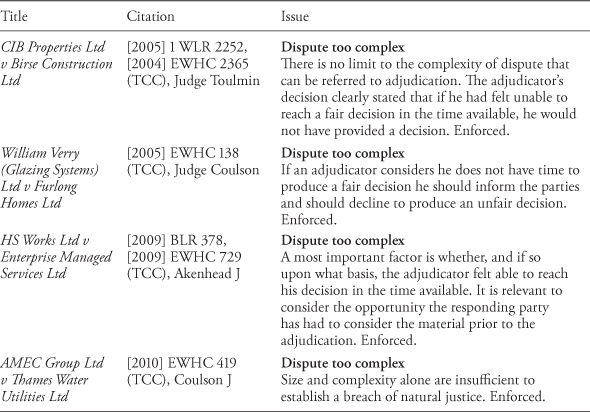

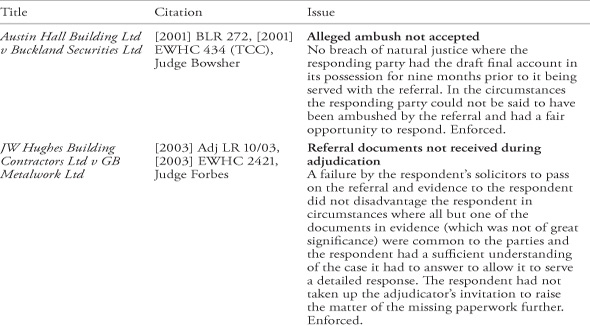

Key Case: Dispute Too Complex

Table 10.1 Table of Cases: Dispute Too Complex

Ambush and Inadequate Opportunity to Respond

10.21 Statutory adjudication (and often contractual adjudication) is by its nature a rapid process which necessarily abbreviates the time available for the responding party to deal with, and the adjudicator to consider, the matters in issue. On enforcement proceedings there is therefore often a plea by the responding party that it was not granted a fair time to deal with the referral with the result that there was a breach of natural justice. Such challenges generally do not succeed.

10.22 The time limits imposed on adjudication and the inherent nature of the procedure undoubtedly place the referring party at an advantage. Since the timetable does not start until the notice of adjudication is served, the referring party has the opportunity to prepare a detailed case over an extended period of time, only giving notice of adjudication when it is satisfied that it has its case in order. By comparison, the response and decision will be required in a very limited period of time, subject to any extensions of time that may be granted. The referring party’s exploitation of this process, often referred to as an ‘ambush’, has been acknowledged as a ‘real public concern’25 and ‘a matter of regret’26 and is considered by some to be an abuse of the adjudication process. However, because the Act permits a referring party to refer a dispute ‘at any time’, it is not uncommon for referring parties to do so ‘in order to obtain the greatest possible advantage from the summary adjudication procedure’.27 Other tactics that could also be categorized as ambush include deliberately referring the matter during holiday periods or holding back material until the adjudication, or even until late in the timetable.

10.23 However, there is at least a degree of protection conferred on responding parties by the requirement that the dispute must have crystallized before it can be referred to adjudication. It is therefore likely that much of the material and arguments will not be new to the responding party. CIB Properties Ltd v Birse Construction Ltd (2005)28 demonstrates that the courts will have little sympathy for a party who fails to use the time following the initial notification of a claim productively. The result is that ambush on its own will not necessarily be enough to found a breach of the rules of natural justice, as confirmed in London & Amsterdam Properties Ltd v Waterman Partnership Ltd (2004) (Key Case):29

179. … mere ambush however unattractive does not necessarily amount to procedural unfairness. It depends upon the case. It may be an important part of the context in which the Adjudicator is required to operate and in which his conduct may fall to be judged in the light of the fundamental common law requirements statutorily underpinned in Section 108 (2)(e) of the Act.

10.24 The courts have enforced decisions where parties have alleged that they did not have enough time to respond;30 or that submission of compendious documents from an earlier adjudication deprived them of a fair opportunity to respond;31 or where a reasonable extension was given to the referring party to deal with a refined and enhanced extension of time claim submitted by the responding party.32

10.25 The only examples of successful challenges have been the result of either not receiving the referral documents at all,33 a late change in the referring party’s case, or late additional evidence that should have been provided with the original referral rather than by way of reply.34

10.26 As with the question of the complexity of the matter as a whole, the primary consideration is whether the adjudicator considers he has time to deal with the matter fairly.35 If the adjudicator considers that there is insufficient time in the adjudication timetable for a party to respond adequately to new issues arising during the course of an adjudication, then the adjudicator should seek the parties’ consent to extend the timetable, or should resign.36 If the adjudicator does neither and then bases the decision on that evidence, then there may be grounds for the decision to be challenged. Akenhead J in Bovis Lend Lease Ltd v Trustees of the London Clinic (2009)37 set out the reasons for this and highlighted the course that should be taken if an adjudicator believes the timetable is insufficient:

51. … [T]he statutory framework of the [1996 Act] is one which enables a party to a construction contract to refer anything, which might be classified as a dispute to adjudication, in the ordinary course of events for a decision to be provided by the adjudicator within 28 days of the reference. Therefore, the threshold to a reference to adjudication is simply and only that there is a crystallised dispute. Thus, if a dispute has arisen by 23rd December in a given year, the referring party may refer that dispute to adjudication on 24 December. That might give rise to an assertion that there has been an ‘ambush’ because the defending party may well have insufficient time, given the Christmas break common in the construction industry, to prepare its defence. It is not uncommon, similarly, for claiming parties to refer matters to adjudication during the summer holidays when it is known that key personnel of the defending party are away. Again, this might be said to be an ‘ambush’. However, for better or for worse, Parliament does not expressly give an adjudicator the power to extend the 28 days by reason of that fact. However, there is a sensible school of thought which suggests that in those circumstances an adjudicator can in effect decline to accept the appointment on the grounds that justice cannot be done or the adjudicator can simply say to the claiming party words to the effect: ‘Unless you agree to an extension of time I will not be able to produce my decision within 28 days.’ Indeed, that is commonly what adjudicators will do and it is a very rare case when the claiming party does not accede to some extension of time accordingly.

10.27 A similar approach was identified in London & Amsterdam Properties Ltd v Waterman Partnership Ltd (2004) (Key Case)38 where Judge Wilcox suggested that the appropriate course of action for an adjudicator to take, where there was late submission of substantial new material but the referring party refused to extend time, was to exclude the late material.

10.28 Whilst some breaches of natural justice may not be apparent until the decision is communicated, a party should be acutely aware at the time it is responding in the adjudication that it faces real difficulties responding in time. Any failure to raise such concerns contemporaneously is likely to be fatal to any subsequent claim that it had inadequate time. For instance, a complaint that an opportunity to make further submissions was denied would appear to be doomed to failure unless such an opportunity was requested at the time.39

10.29 Whether the adjudicator allowing late provision of material will amount to a breach of natural justice will be a question of fact and degree considering the particular circumstances of each case. In Balfour Beatty Construction Northern Ltd v Modus Corovest (Blackpool) Ltd (2008),40 Judge Coulson identified that such a finding would depend on the information concerned, the lateness of that material, whether it could properly be described as an ‘ambush’, the surrounding facts and, most importantly, the adjudicator’s obligation to comply with the timetable.41

10.30 In AWG Construction Services Ltd v Rockingham Motor Speedway Ltd (2004)42 the referring party made out a completely new case in its reply and it was held that the responding party was not given adequate opportunity to deal with the new case. AWG had only five days to respond before the adjudicator issued his decision in which he found in favour of Rockingham on the grounds set out in Rockingham’s late report. Whilst the case was primarily decided on the basis of lack of jurisdiction, it was determined, obiter, that the adjudicator’s failure to afford AWG a proper opportunity to give a fully considered response to the additional material that had been served at such a late stage had clearly prejudiced AWG.

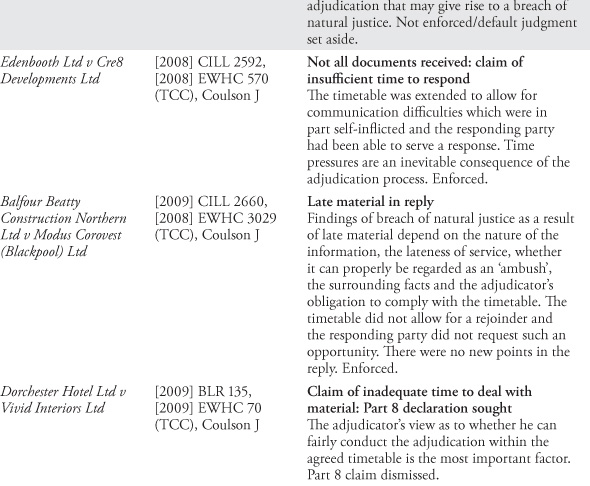

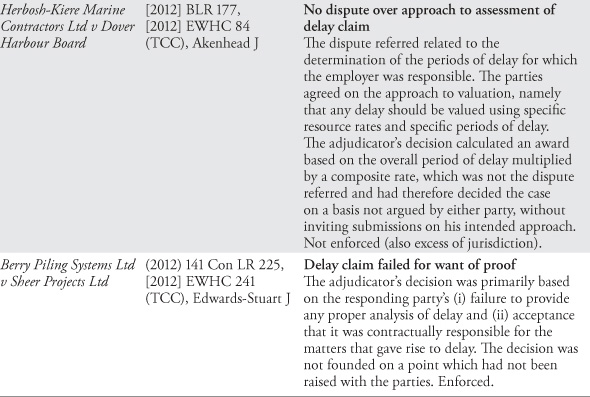

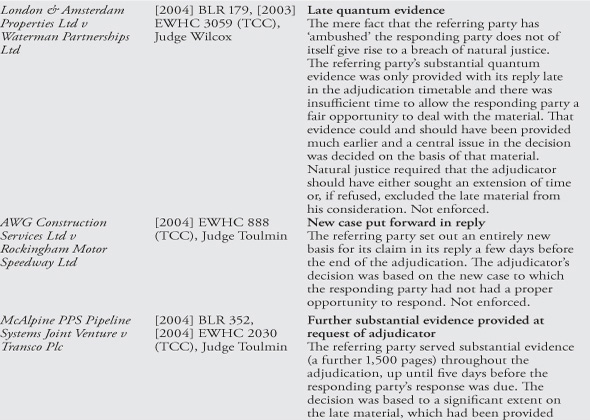

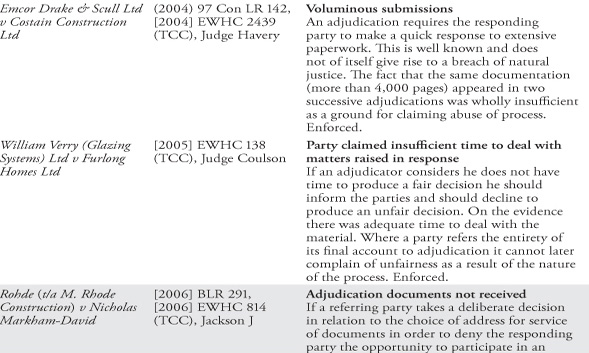

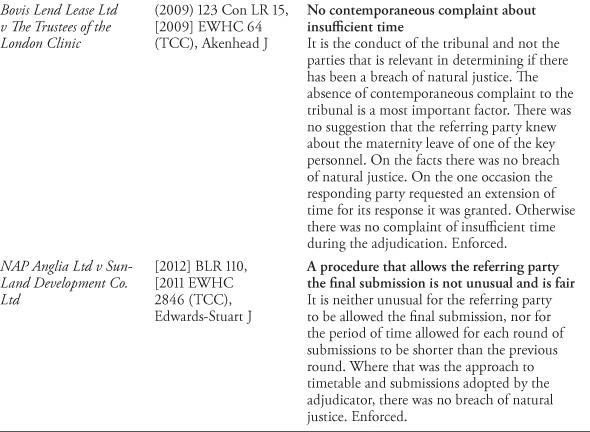

Key Cases: Ambush and Inadequate Opportunity to Respond

Table 10.2 Table of Cases: Ambush and Insufficient Opportunity to Respond (successful challenges are indicated by shaded entries)

Failure to Consider Defence/Counterclaim

10.36 It is frequently the case in construction disputes that both parties consider they have valid claims; for example, a contractor’s claim for payment is often met with a counterclaim for defective work. It is now well settled, as discussed in Chapter 9 on jurisdiction, that the responding party is entitled to raise any defence that is a proper defence in law to the claim being made. It matters not that the matters giving rise to the defence are not set out in the adjudication notice or were not raised or ‘in dispute’ prior to the reference to adjudication.43

10.37 Whilst there is no doubt that a defendant can raise whatever matters it wishes by way of defence for the adjudicator to consider, that general principle does not permit a defendant to rely on a cross-claim which should have been the subject of a withholding notice, but was not. In other words, a defendant cannot avoid the absence of a valid withholding notice if, by reference to the contract and on the facts of the particular dispute, the raising of the cross-claim in question required such a notice. To hold otherwise would be to obviate the need for withholding notices at all.

10.38 The decided cases generally fall into three categories, although some of the earlier decisions in this area have subsequently been doubted. First, where the adjudicator erroneously determines as a matter of jurisdiction alone (where such jurisdictional decisions do not bind the parties) that he cannot consider a defence and therefore ignores it, there will have been a breach of natural justice.44 There is clear injustice where a party is denied having its defence considered on its merits when it should have been, and such errors will generally be considered to be a material breach, as long as the defence has a real, as opposed to fanciful, prospect of success. However, the court will not investigate the facts to determine whether the adjudicator would have reached a different decision had the evidence and argument in question been considered.45

10.39 Secondly, cases where the adjudicator determines on the merits that the defence does not represent a proper legal defence. This often arises as a result of the adjudicator’s determination that the circumstances are such that a withholding notice is required before any sum can be deducted from an interim payment. Such determinations are not determinations as to jurisdiction but are a consideration of the merits of the defence. They will usually require an investigation of the true construction of the payment and withholding notice provisions and a factual investigation of any documents that purport to be notices. If the adjudicator errs in any part of those investigations, that is an error of fact or law made whilst determining a matter within the adjudicator’s jurisdiction and is generally unimpeachable.46

10.40 An adjudicator therefore has to decide whether or not a withholding notice is required to permit a cross-claim to be raised as a defence, and if so, whether or not there has been a valid notice. If he concludes that no notice was required, or that a notice was required and that there was a valid notice, then he must take the cross-claim into account in arriving at his decision. If he concludes that a notice was required, and that either there was no notice or that the notice that has been served was invalid for any reason, then he is entitled to disregard the cross-claim, and the court cannot interfere with that decision: Letchworth Roofing Co. v Sterling Building Co. (2009).47 If the adjudicator wrongly decides that a withholding notice was required and because there was no notice he rejects a defence of set-off, then he has made an error of law rather than a breach of natural justice.48

10.41 Thirdly, where the adjudicator’s decision does not expressly refer to a defence having been considered. Such cases turn on their own particular facts, including the nature of the defence that it is said was ignored and whether it can be said from the terms of the decision that the defence was considered and dismissed. What is clear is that an adjudicator’s decision is not required to expressly refer to each and every defence or alternative defence raised and to recite and address the arguments and why they were considered unpersuasive.49 However, where the terms of the decision suggest that the adjudicator has entirely ignored a fundamental defence, that may well found a material breach of the rules of natural justice.50 An entire defence was expressly ignored in CJP Builders Ltd v William Verry Ltd (2008) (Key Case),51 the adjudicator considering that the applicable adjudication rules did not allow him any discretion to consider a response that was served late or grant an extension of time for service. As a result the adjudication was in effect not contested and the court found that the responding party’s right to be heard had been infringed, albeit entirely innocently and as a result of an erroneous interpretation of the adjudication rules. Whilst such a procedural failure is not strictly an error as to jurisdiction, it is broadly analogous with the cases in the first category. It certainly could not be categorized as a case where the adjudicator had made an error of fact or law whilst considering the merits of the defence.