Can Intellectual Property Help Feed the World? Intellectual Property, the PLUMPYFIELD® Network and a Sociological Imagination

Chapter 8

Can Intellectual Property Help Feed the World? Intellectual Property, the PLUMPYFIELD® Network and a Sociological Imagination

Can intellectual property law help feed the world? Informed by C.W. Mills’ 1959 sociological classic, The Sociological Imagination,1 this chapter begins to answer the question of whether intellectual property law can help feed the world by directly relating and linking intellectual property law with the lives of those affected by food insecurity.2 In exploring the role of intellectual property law in hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity, this chapter begins by suggesting that justifying intellectual property based on advances in technology is compromised by the complexity of food insecurity, and ultimately results in a technology trap; a situation in which intellectual property specifies food security as technology at the expense of the relations in which food is produced, distributed and accessed. The chapter then examines Nutriset’s PlumpyField global supply network, an instance in which intellectual property is being used in the fight against hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity. In the context of food insecurity and intellectual property, then, the PlumpyField network provides a model in which intellectual property can be used as a vehicle for social change. More specifically, the PlumpyField network shows how intellectual property can be used to encourage and support local participation in the manufacture and distribution of food and nutritional products, and, thus, help create a local presence, help build local capacity, facilitate access to food and nutritional products, and ensure the quality of food and nutritional products (as well as broader health and safety standards) in developing countries.

The Technology Trap: How Intellectual Property Specifies Food Security as Technology

Proponents of robust intellectual property protection tend to rely on a direct connection between intellectual property and technological advancement to justify the grant of intellectual property in agricultural research and food production. More specifically, supporters of intellectual property law, particularly patents and plant variety rights, in agricultural research and food production argue that intellectual property is a catalyst for research investment and that they create a positive environment in which new, modified and improved technologies are developed. The traditional argument is: if researchers and companies can protect their innovations, and potentially recoup the costs of investment or even earn a profit, through the use of intellectual property rights, they are more likely to innovate and invent.3 The connection between intellectual property and technological advancement is reflected in Article 7 of the Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property (the ‘TRIPs Agreement’) which sets out the objectives of the intellectual protection and enforcement as ‘contribut[ing] to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare’.4 The corollary of this argument is that, without intellectual property to incentivize agricultural research and food production, there would be less agricultural research, technological development and, ultimately, less food-related innovation.

But, in the context of food insecurity supporting intellectual property based on technological advancement in technology is compromised by the complexity of food insecurity, and by the fact that the link between intellectual property, technology and food security is based on a number of (often unstated) assumptions. One assumption that underpins the use of intellectual property in agricultural research and food production is that food insecurity is caused by a scarcity of food, as well as the related absence of high yielding, pest and climate resilient crops. If, however, we examine the rationale that technological advancement is necessary to overcome the problem of scarcity more closely, and with a sociological imagination, it becomes apparent that developing new technology and producing more food is not the panacea of food insecurity.5 Lappé and Collins, who have been at the forefront of food policy critiques since the 1970s, argue that the source of world hunger is not a lack of food or technology but rather it is colonialism and the subsequent exploitation of multinational companies that are the root causes of world hunger.6 Also, in his book Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Amartya Sen examines a number of famines including the Bengal Famine of 1943, the Ethiopian Famine of 1972-4 and the Famine of Bangladesh in 1974, and argues that it is a loss of capability or entitlement rather than a scarcity of food that leads to famine. At the time, Sen’s capabilities and entitlement approach challenged the Malthusian logic that there is simply too many people and not enough food, and shifted the focus of away from food production towards issues of ownership and exchange of food or other goods that provide the money to purchase food.7 Significantly, Sen argues that in many cases of famine food supplies are not, in absolute terms, insufficient and on this point he is worth quoting at length:

Sometimes famines have coincided with years of peak food availability, as in the Bangladesh famine of 1974. Even when a famine is, in fact, associated with a decline in food production, we still have to go beyond the output statistics to explain why it is that some parts of the population get wiped out, while the rest do just fine. Since food and other commodities are not distributed freely, people’s consumption depends on their ‘entitlements’, that is, on the bundles of goods over which they can establish ownership through production and trade, using their own means. Some people own the food they themselves grow, while other buy them in the market on the basis of incomes earned through employment, trade or business. Famines are initiated by a severe loss of entitlements of one or more occupation groups, depriving them of the opportunity to command and consume food. Famines survive by divide and rule. For example, a group of peasants may suffer entitlement loss when food output in their territory declines, perhaps due to a local drought, even when there is no general dearth of food in the country. The victims would not have the means to buy food from elsewhere, since they wouldn’t have anything much to sell to earn an income, given their own production loss. Others with more secure earnings in other occupations or in other locations may be able to get by well enough by purchasing food from elsewhere.8

That food insecurity is a problem of access, as well as production, is exemplified by the so-called ‘food crisis’ of 2007-8 that occurred around the world in countries such as Morocco, Egypt, Italy, Haiti, Jordan, the Philippines, Argentina and Mexico.9 In Mexico for example, tortillas (which have been a staple food in Mexico for thousands of years) became too expensive for much of the Mexican population. This was due to a range of complex, related factors. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force in 1994 between the United States, Canada and Mexico to create the world’s largest free trade area. While the objectives of the NAFTA include reducing barriers to trade in North America, improving working conditions in North America and creating a safe market for goods and services produced in North America, the NAFTA also tied Mexican corn production to the North American market. In the early 2000s, climate change became a driving force in international, regional and national policy and numerous countries introduced laws and regulation encouraging the use of agro-fuels. In 2005, the United States Congress, for example, established various measures to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions by encouraging the development and use of renewable fuels; leading, in 2007, to the introduction of the Renewable Fuels Standards program which set an agro-fuel mandate that encouraged the use of corn as fuel.10

Unsurprisingly, the demand for corn for use as a fuel increased substantially in the United States during the mid-2000s, leaving many farmers with little choice but to use their land for the production of corn for agro-fuel rather than for food.11 As McMichael summarizes the situation: ‘through rising demand for agro-fuels, and feed crops – to exacerbate food price inflation as their mutual competition for land has the perverse effect of rendering each crop more lucrative, as they also displace land used for food crops’.12 In Mexico, the effect of this was that corn production moved away from contributing to staple foods such as tortillas and towards agro-fuels for the high value United States market. As a consequence Mexico, a country defined by corn, had to import corn from the United States and, as a consequence, the price of tortillas doubled during 2006.13 So devastating has been the confluence of the NAFTA and the demand for agro-fuels on food supply that, on 9 August 2012 the Director General of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), José Graziano da Silva, called on the United States to suspend its ethanol mandate so that more crops, particularly corn, could be diverted back to food production.14

Another assumption that underpins and informs the use of intellectual property in agricultural research and food production is that intellectual property leads to crop improvement, and that ultimately this will lead to food security. Although the question of whether intellectual property law provides an incentive for technological development has been asked for decades, incentive-based rationales for intellectual property have proven difficult to substantiate.15 Robert Merges sums up the problem of demonstrating that intellectual property provides an incentive to innovate or create in the following way:

Estimating costs and benefits, modelling them over time, projecting what would happen under counterfactuals (such as how many novels or pop songs really would be written in the absence of copyright protection, and who would benefit from such a situation) – these are all overwhelmingly complicated tasks. And this problem poses a major problem for utilitarian theory. The sheer practical difficulty of measuring or approximately all the variables involved means that the utilitarian program will always be at best aspirational.16

In addition to the broader questions about whether intellectual property provides an incentive for technological development, the impact of technology on food insecurity is unclear. Although there have been attempts empirically to assess the impact of technology on food security, this, in a similar way to proving that intellectual property law provides an incentive for technological advancement, has proven difficult.17 In keeping with a sociological imagination when thinking about the effect of technology on food security, it is helpful to consider the people affected by technological advances in agriculture and food production rather than merely focusing on the technological advances related to agriculture and food production. In this way the so-called Green Revolution is an ideal site to scrutinize the effect of technological advances and crop improvement on food security.

First used in 1968 by William Gaud, the Director of the United States Agency for International Development, the phrase ‘the Green Revolution’ refers to a period of technological advancement that began in the 1940s and lasted until the late 1970s. This period was characterized by the modernization of agriculture through a suite of measures including improved crop varieties, irrigation, fertilizers, pesticides, extension services and the availability of credit to famers.18 There is no denying that the Green Revolution had a significant impact on agriculture, for example: wheat production in Pakistan increased by 60 per cent from 1967 to 1969; India achieved self-sufficiency in cereals in the mid-1970s; and Indonesia’s rice yields nearly doubled from 1965 to 1989.19 As one commentator noted: ‘history records no increase in food production that was remotely comparable in scale, speed and duration’.20 Despite the increases in food production, the impact of the Green Revolution on food security is less clear. Critics of the Green Revolution question whether technological advances – such as improved corn, wheat and rice varieties – resulted in a significant and lasting impact on food security. A review of 300 studies on the Green Revolution published between 1970 and 1989 shows that the effect of the Green Revolution’s improved crop varieties was inconsistent at best: in fact, 80 per cent of the articles reviewed concluded that the Green Revolution increased inequality.21 More specific condemnation of the Green Revolution has focused on the fact that to be effective the technology developed required considerable resources such as fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation and machinery; all of which are not always readily available in developing countries.22 Furthermore, uptake of technology is dependent on policy, the availability of loans, credit or subsidies, and the availability of the necessary infrastructure such as roads, railways and ports.23 According to critics, the Green Revolution also assumes a one-size-fits-all approach, and, as a consequence, had little impact on developing countries such as Africa which had institutional and structural problems, political and economic instability, corruption and an absence of resolve to make meaningful, long-term change.24

When thinking about the role that intellectual property law plays (or might play) in feeding the world it is important to keep in mind that food insecurity is a complex physical, economic, political and social problem. Too often, however, it is assumed that crop improvement is the panacea of food insecurity, and, thus, intellectual property is justified on the grounds that it provides the necessary incentives for crop improvement and food production. While this might be true in some circumstances – and there are a range of technological innovations such as transgenic crops, fertilizers and pesticides that can potentially increase agricultural productivity – merely focusing on the relationship between intellectual property and technological advancement leads to a technology trap: a situation in which food security is specified as technology at the expense of the relations in which food is produced, accessed and distributed. Avoiding the technology trap is particularly important because, despite advances in technology and food production, hundreds of millions of people are hungry not because of an absolute scarcity of food but because they lack the means to produce or purchase the food that they need for a healthy and productive life.25 With this is mind, the remainder of this chapter examines Nutriset’s PlumpyField global supply network of food and nutritional products, an example of intellectual property being used to encourage and support the participation of entities in developing countries in the manufacture of food and nutritional products.

The PLUMPYFIELD® Global Supply Network: Using Intellectual Property to Encourage and Support Local Participation

Established in 1986, Nutriset is a for-profit company based in France that specializes in developing food and nutritional products that are used to prevent and treat malnutrition and diarrhoea in developing countries. Nutriset is best known for developing, in partnership with the Institut de Recherché pour le Développement (IRD), the first peanut-based ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition known as Plumpy’Nut. Plumpy’Nut comes in a 92 gram foil packet, provides around 500 kcal and is enriched with vital vitamins and minerals. It does not need refrigeration, cooking or water, and lasts up to two years. So effective is Plumpy’Nut in treating acute malnutrition that it is one of the most widely used therapeutic solutions to fight child malnutrition and is used by a number of world health agencies including the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Food Programme (WFP). In addition to Plumpy’Nut, Nutriset have developed a wide range of food and nutritional products including Plumpy’Doz, Plumpy’Sup, Nutributter, QBmix and Plumpy’Soy.26

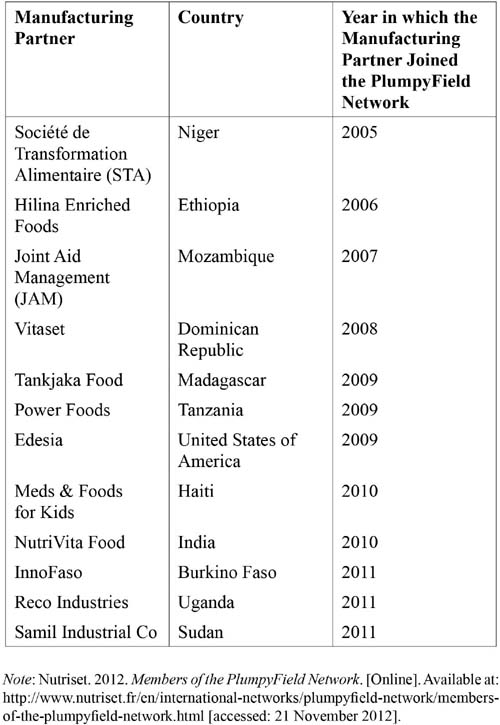

In response to an increase in demand for Plumpy’Nut, as well as pressure to permit local production of Plumpy’Nut, Nutriset’s food and nutritional products and services are distributed to developing countries largely through the PlumpyField network.27 Formalized in 2005, the PlumpyField supply network is a franchising scheme that provides developing countries with access to Nutriset’s products as well as information and know-how about technical matters such as production processes, quality control and management, and staff training. Importantly, the PlumpyField network, and the more recent ZincField network, have been established to allow Nutriset to monitor and control the production of its food and nutritional products.28 By having a high level of involvement and control over the manufacture of their products, Nutriset contend that they are able to do more than merely supply food and nutritional products to those in need. More specifically Nutriset argue that through the PlumpyField network they are able to exclude companies in developed countries from producing Nutriset’s products, and can instead, encourage and support local partners in the (developing) countries to produce their own food and nutritional products. In so doing, Nutriset argue that they are increasing the economic and social effect of their products in developing countries. In 2012, 12 of the 13 PlumpyField manufacturing partners were based in developing countries (see Table 8.1).

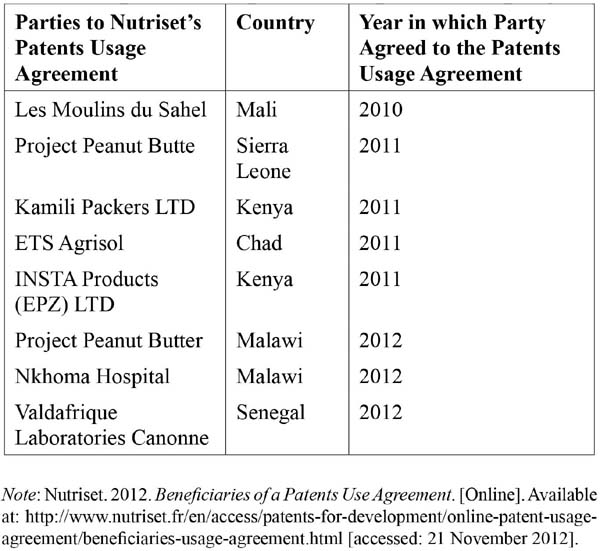

In addition to the PlumpyField and ZincField networks, Nutristet uses online Patents Usage Agreements to grant non-exclusive licences to entities in developing countries.29 The aim of the Patents Usage Agreements is to ‘allow companies in developing nations to benefit from [Nutriset’s] common patents and, for this purpose, enter into Usage Agreement via a simplified internet-based system’. To be eligible for the Patents Usage Agreement entities must be local non-government organizations, and must ‘have its production and business site, activity, headquarters, and main shareholders (at least 51% of the share capital) based’ in one of the developing countries in which Nutriset has valid patent rights.30 According to Nutriset, these countries include Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Uganda, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Chad, Togo and Zimbabwe. While the ‘beneficiaries’ of the Patents Usage Agreement are granted non-exclusive authorization to use Nutriset’s patents, they do not receive the associated benefits of joining the Plumpy’Field network. More specifically, in return for being permitted to use the processes and methods needed to prepare (similar) products to those developed by Nutriset the licensee must ‘develop its own formulae, recipes and Products, without assistance from Nutriset and the IRD’,31 ‘undertake to develop and implement its own quality system’32 and not ‘reproduce and/or imitate the brands, logos, packaging, graphic identity or any other distinctive signs used by Nutriset for its own products, packaging and communication media’.33 Whilst it is not compulsory for the patent licensee to pay a licence fee they are ‘invited’ to make a 1 per cent contribution of the turnover earned by the sales of the products included in the Usage Agreement to fund the IRD’s research and development.34 As of 10 December 2012 six entities have signed up to the Patents Usage Agreement (see Table 8.2).

One of the reasons why Nutriset is able to adopt a franchise and licensing system is because they hold intellectual property over some of their products, names and brands.35 The most well-known of Nutriset’s intellectual property is the Plumpy’Nut patent which is registered with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) with the title High Energy Complete Food or Nutritional Supplement, Method for Preparing Same and Uses Thereof.36 The Plumpy’Nut patent has been registered with the French patent office, the Canadian Intellectual Property Office, the European Patent Office and the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Perhaps most importantly, however, Nutriset has strategically sought, and been granted, patents in a number of developing countries including Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Uganda, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Chad, Togo and Zimbabwe.37 Somewhat contentiously, the Plumpy’nut patent is broadly written and covers a number of products as well as processes for making Plump’nut. The Plumy’nut patent has 23 claims that include, for example, a:

Table 8.2 Parties to Nutriset’s Patents Usage Agreement

[p]rocess for the preparation of a complete food or food complement according to claim 1, wherein all or part of the products which provide carbohydrates, the products which provide proteins, and the vitamins, minerals, enzymes and additives is mixed, the products which provide lipids and the coating substance are then added to this mixture, the ingredients are mixed again and the resulting product is then poured into the pack.38

In addition to holding patent rights in both developed and developing countries Nutriset have several registered trade marks. The names PlumpyField, ZincField, Plumpy’Nut, Plumpy’Doz and Nutributter are registered trade marks in a range of jurisdictions world-wide, including the Unites States and some developing countries. The word PlumpyField, for example, is registered under International Classification 35 (for goods and services related to business management and consultancy, particularly for a franchisor in the field of food production and preparation intended for the prevention and the fight against malnutrition) and the word Plumpy’Nut is registered under International Classification 5 (for food and substances adapted for medical uses, and dietary supplements for human consumption).

One of the defining features of intellectual property is that they enable the owner to control who has access to the products, processes or brands that are protected. Indeed, Nutriset’s franchise and licensing strategy is largely made possible by the fact that they have sought, and been granted, intellectual property in both developed and developing countries. By proactively using and defending its intellectual property, Nutriset is able to exert control over whom, and under what circumstances, their products and services are used. Generally speaking, manufacturers only obtain permission to use Nutriset’s registered patents and trade marks once they have joined the PlumpyField network. Take, for example, the Indian-based company NutriVita Food which was formed in 2010 to ‘eradicate under-nourishment and create a healthy and well nourished younger generation’ in India. NutriVita Food became a PlumpyField member in 2010 and in so doing obtained permission from Nutriset to manufacture and distribute Nutriset’s patented products – including Plumpy’Nut, Plumpy’Sup and Plumpy’Doz. As a PlumpyField member, NutriVita Food can also use the associated PlumpyField, Plumpy’Nut, Plumpy’Sup and Plumpy’Doz trade marks, packaging and branding (see Figures 8.1 and 8.2).

© Nutriset – all rights reserved.

Building Nutritional Autonomy by Creating a Local Presence, Increasing Local Capacity, Facilitating Access and Ensuring the Quality Food Products

By using their patent and trade mark rights to control access to their products, processes and brands Nutriset hopes to encourage and support local participation in the production and distribution of its food and nutritional products. Indeed, one of the underlying principles of the PlumpyField global network, as well as Nutriset’s Patents Usage Agreement, is nutritional autonomy. Defined by Nutriset as ‘[t]he capacity of a country or community to set up a sustainable system to identify and make accessible the nutrients required for the development and good health of its population’,39 nutritional autonomy is similar to the more commonly used concept of food sovereignty. First proposed by the international farmers’ advocacy, Via Campesina in the mid-1990s at the World Food Summit, food sovereignty – which was defined in 2007 at an international forum on food sovereignty as ‘the right of peoples to define their own food and agriculture; to protect and regulate domestic agricultural production and trade in order to achieve sustainable development objectives; to determine the extent to which they want to be self-reliant; to restrict the dumping of products in their markets’40 – has come to be a rallying call that is in part a response to the dominance of large corporate-driven food production and the proliferation of free trade policies. With its emphasis on local food systems, putting control and knowledge in the hands of local farmers and local manufacturers, food sovereignty movements are seen as long-term solutions to alleviate hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity.41

The significance of locally oriented solutions to the long-term alleviation of hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity is underlined by criticisms of alternative forms of assistance that are provided to developing countries. One form of assistance, food aid, is a multifaceted approach that is largely driven by international donors and international organizations such as the United Nations’ WFP and FAO. Food aid is often provided in the form of in-kind or subsidized deliveries of food and nutritional products. Traditionally, one of the main strategies of international food aid has been to export food and nutritional products from developed countries to those countries in need.42 Another form of assistance increasingly being used to respond to hunger, malnutrition and poverty is the social business model known as ‘buy one give one’. The ‘buy one give one’ model is an approach in which companies donate products or services to countries or individuals in need every time a customer buys one of their products. One of the largest and most well-known ‘buy one give one’ businesses is Toms shoes; a United States based company founded in 2006 that, for every pair of shoes that someone buys, gives a pair shoes to a child in need.43 An example of a food-based ‘buy one give one’ business is Two Degrees of Food. Based in the United States, Two Degrees of Food has the slogan ‘Buy a Bar: Give a Meal’, and, have, according to their own website, ‘committed’ over 500,000 meals to those in need.44