Bringing Human Rights into Public Health

Bringing Human Rights into Public Health

Introduction

What role do human rights have in public health work? Since the early stages of the women’s health, reproductive health, and indigenous health movements it has been asserted that public health policies and programs must be cognizant and respectful of human rights norms and standards. It has also been stated that lack of respect for human rights hampers the effectiveness of pubic health policies and programs. For the last decade or so, an interdisciplinary ‘health and human rights’ movement has been generating scholarship and inspiring programming intended to realize ‘‘the highest attainable standard of health’’ (UN International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, 1966; Gruskin and Tarantola, 2001) with a particular focus on the most underserved and marginalized populations and human rights language has been integrated into numerous national and international public health strategies, such as those embraced by UNAIDS (2005, 2006). Yet moving beyond the rhetoric, there is still diversity of opinion as to what this means in practice.

Given that many public health practitioners are interested in the application of human rights to their work even as they are unsure what besides having a good heart this means for their efforts, as a first step an understanding of some aspects of human rights is necessary. In the present chapter we attempt to set out what application of these concepts has meant to date in practice, discuss ‘rights-based’ approaches to health, and suggest questions and concerns for the future.

Although this chapter will not seek to incorporate bioethical frameworks into the discussion, it is important to recognize the long-standing relationship of those working in bioethics and those working in human rights in relation to health (see, e.g., UNESCO, 2005). The two fields are distinct, but they do overlap particularly in relation to instituting international guidelines for research via professional norm-setting modes. Human rights and ethics in health are closely linked, both conceptually and operationally (Mann, 1999; Gruskin and Dickens, 2006). Each provides unique, valuable, and concrete guidance for the actions of national and international organizations focused on health and development. Public health workers should appreciate their distinct value, but also the differences in the paradigms they represent in particular with respect to means of observance, action, and enforcement. The similarities and differences between bioethics and human rights frameworks for strengthening protections in relation to health are beginning to be explored but are outside the scope of the present chapter.

In the work of public health we have learned that explicit attention to human rights shows us not only who is disadvantaged and who is not, but also whether a given disparity in health outcomes results from an injustice. Human rights are now understood to offer a frame-work for action and for programming, as well as providing a compelling argument for government responsibility—not only to provide health services but also to alter the conditions that create, exacerbate, and perpetuate poverty, deprivation, marginalization, and discrimination (Gruskin and Braveman, 2005). A diverse array of actors are increasingly finding innovative ways to relate human rights principles to health-related work, thereby demonstrating how a human rights perspective can yield new insights and more effective ways of addressing health needs within country settings as well as in the policy and programmatic guidance offered at the global level.

Approaches to Bringing Human Rights into Health Work

Over time it has become clear that people tend to work in a variety of ways to further work on health and human rights, and that while some take health as an entry point, others take human rights and no one approach has primacy as the only way to make these connections. Despite this diversity, the frameworks within which they operate can be generally assigned to four broad categories: advocacy, legal, policy, and programs. We summarize each framework briefly as follows.

Advocacy Frameworks

Advocacy is a key component of many organizations’ work in health and human rights. Work in the advocacy category can be described as using the language of rights to draw attention to an issue, mobilize public opinion and advocate for change in the actions of governments and other institutions of power. Advocacy efforts may call for the implementation of rights even if they are not yet in fact established by law, and in so doing serve to move governmental and inter-governmental bodies closer to legitimizing these issues as legally enforceable human rights claims. This means also linking of activists working on issues related to health (such as groups focused on violence against women, poverty and global trade issues), reaching out to policy makers and other influential groups, translating international human rights norms to the work and concerns of local communities, and supporting the organizing capabilities of affected communities to push for change in legal and political structures. An example of an advocacy approach is the People’s Health Movement (PHM), a civil society initiative created in 2000, bringing together individuals and organizations committed to the implementation of the Alma-Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care (Declaration of Alma-Ata, 1978; The People’s Health Charter, 2005). In 2006, The PHM launched a campaign ‘‘To promote the Health for All goal through an equitable, participatory and intersectoral movement and as a rights issue’’ (Right to Health and Health Care Campaign, 2006).

Legal Frameworks

This approach prioritizes the role of human rights law at international and national levels in producing norms, standards, and accountability in health-related efforts. This includes engaging with law in the formal sense, including building on the consonance between national law and international human rights norms, for example, to promote and protect the rights of people living with HIV/AIDS through litigation and other means. Pursuing legal accountability through national law and international treaty obligations often takes the form of analyzing what a government is or is not doing in relation to health and how this might constitute a violation of rights, seeking remedies in national and international courts and tribunals and focusing on transparency, accountability, and functioning norms and systems to promote and protect health-related rights. Examples of a legal approach include recent court cases in Latin America and in South Africa focused on access to antiretroviral therapy by people living with HIV, invoking in particular the right to life and the right to health (Carrasco, 2000; Nattrass, 2006). There, constitutional provisions and international human rights treaties were used to challenge the inaction or opposition of governments to the procurement and availability of drugs alleged to be beyond the economic means of the state or, in the case of South Africa, lacking scientific evidence of their safety and efficacy (Elliott, 2002; PAHO, 2006).

Policy Frameworks

This approach looks to instituting human rights norms and standards mostly through global and national policymaking bodies from health, economic, and development perspectives. These include human rights norms or language as it appears in the documents and strategies that emanate from these bodies as well as the approach taken to operationalize human rights work within an organization’s individual programs and departments. In addition to the inclusion of human rights norms within recent global consensus documents such as the UN General Assembly Special Session on AIDS (UN, 2006), a large and growing number of national and international entities have formulated rights-based approaches to health in the context of their own efforts. Among these are several official development assistance organizations and agencies, funds, and programs of the United Nations System. (These agencies include UNAIDS, UNICEF, UNDP, UNFPA, DFID, as well as Canadian CIDA and Swedish SIDA.)

Programmatic Frameworks

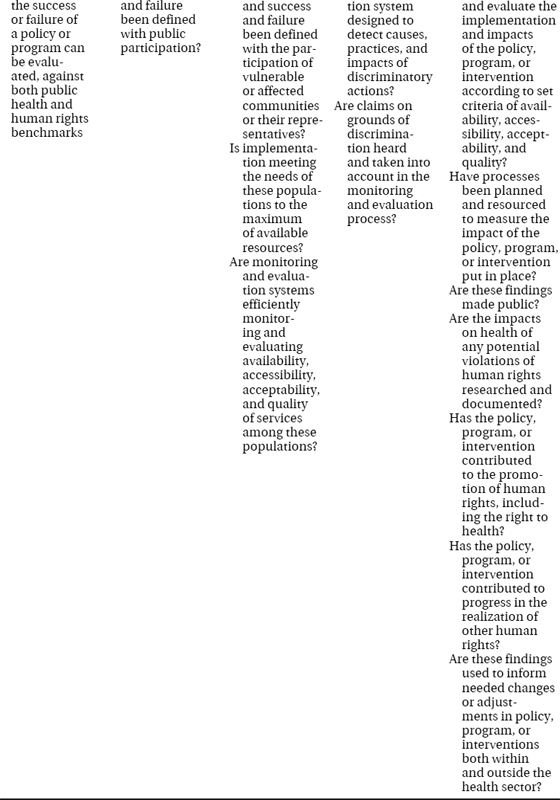

This approach is concerned with the implementation of rights in health programming. This includes the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of health programs, including what issues are prioritized and why, at different stages of the work. Often these efforts are carried out by large international organizations, including both inter-governmental and nongovernmental entities. In general, work in this category refers to inclusion of key human rights components within programmatic initiatives and in daily practice such as ensuring attention to the participation of affected communities, nondiscrimination in how policies and programs are carried out, attention to the legal and policy context within which the program is taking place, transparency in how priorities were set and decisions were made, and accountability for the results. Examples with respect to this category are discussed in more detail below.

As the health and human rights field has become more strongly rooted in robust human rights principles and sound public health, it is appropriate that such different interpretations and applications to practice are coming forward. This has, however, unfortunately, in many ways fuelled the lack of clarity as to what added-value human rights offer to public health work. Despite significant differences, work which falls under these different rubrics is often amalgamated under what is called a ‘rights-based approach’ to health, and these are in themselves ‘all over the map,’ whether encompassing legal, advocacy, or programmatic efforts. One can say that it is a great accomplishment of all those who have fostered the dialogue around ‘rights-based approaches to health’ that this term is now being used to characterize such a wide range of activities. A great challenge is that the term is used in very different ways by different institutions and individuals. At worst, the inconsistencies in how ‘rights-based approaches to health’ are conceptualized threaten to undo major accomplishments. At best, the diversity in interpretation of what is meant by ‘rights-based approaches to health’ means the field is alive and well.

The Elusive Rights-Based Approach to Health

Ultimately much of the work to bring human rights into public health is looking at synergies and trade-offs between health and human rights and working, within a framework of transparency and accountability, toward achieving the highest attainable standard of health. Central in all settings are the principles of nondiscrimination, equality, and to the extent possible the genuine participation of affected communities. This does not mean a one-size-fits-all approach. In addition to differences in frameworks, the rights issues and the appropriateness of policies and programs relevant to one setting with one population might not be so in a different setting to another.

Initially conceptualized in the mid-1990s as a ‘human rights based approach to development programming’ by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 1998), rights-based approaches have been applied to specific populations (e.g., children, women, migrants, refugees, and indigenous populations), basic needs (e.g., food, water, security, education, and justice), health issues (e.g., sexual and reproductive health, HIV, access to medicines), sources of livelihood (e.g., land tenure, pastoral development, and fisheries), and the work of diverse actors engaged in development activities (e.g., UN system, governments, NGOs, corporate sector). Even as health cuts across all of these areas and is regarded both as a prerequisite for and an important outcome of development, the understanding of what a rights-based approach actually means for public health efforts varies across sectors, disciplines, and organizations.

In order to define the core principles of rights-based approaches (RBAs) applicable across all sectors of development, including health, a ‘‘Common Understanding’’ was elaborated by the UN system in 2003 (UN, 2003). In short, it suggests that the following points are critical for identifying a rights-based approach: all programs should intentionally further international human rights; all development efforts, at all levels of programming, must be guided by human rights standards and principles founded in international human rights law; and all development efforts must build the capacity of ‘‘duty bearers’’ to meet obligations and/or ‘‘rights holders’’ to claim rights (UN, 2003 May).

UN Statement of Common Understanding of the Human Rights-Based Approach to Development

- All programmes of development cooperation, policies and technical assistance should further the realisation of human rights as laid down in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments.

- Human rights standards contained in, and principles derived from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments guide all development cooperation and programming in all sectors and in all phases of the programming process.

- Development cooperation contributes to the development of the capacities of ‘duty-bearers’ to meet their obligations and/or of ‘rights-holders’ to claim their rights.