Chapter 13 Basis of property ey.com/EYTaxGuide

This chapter discusses how to figure your basis in property. It is divided into the following sections.

Cost basis. Adjusted basis. Basis other than cost. Your basis is the amount of your investment in property for tax purposes. Use the basis to figure gain or loss on the sale, exchange, or other disposition of property. Also use it to figure deductions for depreciation, amortization, depletion, and casualty losses.

If you use property for both business or investment purposes and for personal purposes, you must allocate the basis based on the use. Only the basis allocated to the business or investment use of the property can be depreciated.

Your original basis in property is adjusted (increased or decreased) by certain events. For example, if you make improvements to the property, increase your basis. If you take deductions for depreciation or casualty losses, or claim certain credits, reduce your basis.

You may want to see:

15-B Employer’s Tax Guide to Fringe Benefits525 Taxable and Nontaxable Income535 Business Expenses537 Installment Sales544 Sales and Other Dispositions of Assets550 Investment Income and Expenses551 Basis of Assets946 How To Depreciate Property The basis of property you buy is usually its cost. The cost is the amount you pay in cash, debt obligations, other property, or services. Your cost also includes amounts you pay for the following items:

Sales tax, Freight, Installation and testing, Excise taxes, Legal and accounting fees (when they must be capitalized), Revenue stamps, Recording fees, and Real estate taxes (if you assume liability for the seller). In addition, the basis of real estate and business assets may include other items.

Loans with low or no interest. If you buy property on a time-payment plan that charges little or no interest, the basis of your property is your stated purchase price minus any amount considered to be unstated interest. You generally have unstated interest if your interest rate is less than the applicable federal rate.

For more information, see Unstated Interest and Original Issue Discount (OID) in Publication 537.

Real property, also called real estate, is land and generally anything built on, growing on, or attached to land.

If you buy real property, certain fees and other expenses you pay are part of your cost basis in the property.

Lump sum purchase. If you buy buildings and the land on which they stand for a lump sum, allocate the cost basis among the land and the buildings. Allocate the cost basis according to the respective fair market values (FMVs) of the land and buildings at the time of purchase. Figure the basis of each asset by multiplying the lump sum by a fraction. The numerator is the FMV of that asset and the denominator is the FMV of the whole property at the time of purchase.

Fair market value (FMV). FMV is the price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller, neither having to buy or sell, and both having reasonable knowledge of all the necessary facts. Sales of similar property on or about the same date may be helpful in figuring the FMV of the property.

Assumption of mortgage. If you buy property and assume (or buy the property subject to) an existing mortgage on the property, your basis includes the amount you pay for the property plus the amount to be paid on the mortgage.

Settlement costs. Your basis includes the settlement fees and closing costs you paid for buying the property. (A fee for buying property is a cost that must be paid even if you buy the property for cash.) Do not include fees and costs for getting a loan on the property in your basis.

The following are some of the settlement fees or closing costs you can include in the basis of your property.

Abstract fees (abstract of title fees). Charges for installing utility services. Legal fees (including fees for the title search and preparation of the sales contract and deed). Recording fees. Survey fees. Transfer taxes. Owner’s title insurance. Any amounts the seller owes that you agree to pay, such as back taxes or interest, recording or mortgage fees, charges for improvements or repairs, and sales commissions. Settlement costs do not include amounts placed in escrow for the future payment of items such as taxes and insurance.

The following are some of the settlement fees and closing costs you cannot include in the basis of property.

Casualty insurance premiums. Rent for occupancy of the property before closing. Charges for utilities or other services related to occupancy of the property before closing. Charges connected with getting a loan, such as points (discount points, loan origination fees), mortgage insurance premiums, loan assumption fees, cost of a credit report, and fees for an appraisal required by a lender. Fees for refinancing a mortgage. Real estate taxes. If you pay real estate taxes the seller owed on real property you bought, and the seller did not reimburse you, treat those taxes as part of your basis. You cannot deduct them as an expense.

If you reimburse the seller for taxes the seller paid for you, you can usually deduct that amount as an expense in the year of purchase. Do not include that amount in the basis of your property. If you did not reimburse the seller, you must reduce your basis by the amount of those taxes.

Points. If you pay points to get a loan (including a mortgage, second mortgage, line of credit, or a home equity loan), do not add the points to the basis of the related property. Generally, you deduct the points over the term of the loan. For more information on how to deduct points, see chapter 24

Points on home mortgage. Special rules may apply to points you and the seller pay when you get a mortgage to buy your main home. If certain requirements are met, you can deduct the points in full for the year in which they are paid. Reduce the basis of your home by any seller-paid points.

Before figuring gain or loss on a sale, exchange, or other disposition of property or figuring allowable depreciation, depletion, or amortization, you must usually make certain adjustments (increases and decreases) to the cost basis or basis other than cost (discussed later) of the property. The result is the adjusted basis.

Increase the basis of any property by all items properly added to a capital account. Examples of items that increase basis are shown in Table 13-1 . These include the items discussed below.

Improvements. Add to your basis in property the cost of improvements having a useful life of more than 1 year, that increase the value of the property, lengthen its life, or adapt it to a different use. For example, improvements include putting a recreation room in your unfinished basement, adding another bathroom or bedroom, putting up a fence, putting in new plumbing or wiring, installing a new roof, or paving your driveway.

When you sell your home, your gain or loss is measured by the difference between the price you receive on the sale and your basis. Any improvements you have made will have increased your basis and will now decrease your tax liability. It is important that you keep adequate records of all improvements and selling expenses, including the following:

Replacing the roof Installing permanent storm windows Installing new plumbingInstalling a new heating or air-conditioning system Installing a new furnace Restoring a rundown house Landscaping: adding new trees, shrubs, or lawn Building a swimming pool, tennis court, or sauna Constructing or improving a driveway Constructing walks Constructing patios and decks Constructing walls Kitchen or bathroom remodeling, including cost of new appliances Payment of legal fees stemming from improvements, zoning, and so on Payment of real estate commissions Other selling expenses, such as advertising or paying professional fees related to staging your property Payment of closing costs It is important to distinguish between expenditures that constitute additions to basis and those that constitute repairs. If the asset is used in a trade or a business, repairs are deductible, but do not increase its basis. If the asset is personal, the costs of repairs are not deductible and do not increase the asset’s basis. For a more complete discussion of this matter, see chapter 9 Rental income and expenses .

As noted by the IRS, your basis in property is reduced by money you receive as a return of capital. See chapter 8 Dividends and other corporate distributions , for further details.

Example

You buy land and a building for $25,000 for use as a parking lot. You pay $3,000 to have the building torn down, and you sell some of the materials you salvage from it for $5,000. You figure your adjusted basis in the property by taking your $25,000 initial cost, adding the $3,000 you spent for tearing down the building, and subtracting the $5,000 you received for the materials you salvaged. Your adjusted basis for the lot is $23,000. The money you received from the sale of the salvaged materials is not income, and the cost of tearing down the building is not deductible.

Table 13-1

Increases to Basis Decreases to Basis • Capital improvements: • Exclusion from income of subsidies for energy conservation measures

Assessments for local improvements. Add to the basis of property assessments for improvements such as streets and sidewalks if they increase the value of the property assessed. Do not deduct them as taxes. However, you can deduct as taxes assessments for maintenance or repairs, or for meeting interest charges related to the improvements.

Example. Your city changes the street in front of your store into an enclosed pedestrian mall and assesses you and other affected property owners for the cost of the conversion. Add the assessment to your property’s basis. In this example, the assessment is a depreciable asset.

Decrease the basis of any property by all items that represent a return of capital for the period during which you held the property. Examples of items that decrease basis are shown in Table 13-1 . These include the items discussed below.

Casualty and theft losses. If you have a casualty or theft loss, decrease the basis in your property by any insurance proceeds or other reimbursement and by any deductible loss not covered by insurance.

You must increase your basis in the property by the amount you spend on repairs that restore the property to its pre-casualty condition.

For more information on casualty and theft losses, see chapter 26

Depreciation and Section 179 deduction. Decrease the basis of your qualifying business property by any Section 179 deduction you take and the depreciation you deducted, or could have deducted (including any special depreciation allowance), on your tax returns under the method of depreciation you selected.

For more information about depreciation and the Section 179 deduction, see Publication 946 and the Instructions for Form 4562.

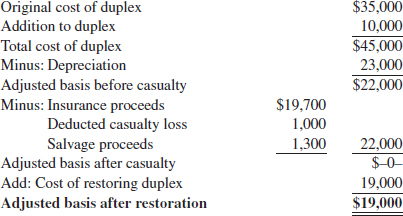

Example. You owned a duplex used as rental property that cost you $40,000, of which $35,000 was allocated to the building and $5,000 to the land. You added an improvement to the duplex that cost $10,000. In February last year, the duplex was damaged by fire. Up to that time, you had been allowed depreciation of $23,000. You sold some salvaged material for $1,300 and collected $19,700 from your insurance company. You deducted a casualty loss of $1,000 on your income tax return for last year.

You spent $19,000 of the insurance proceeds for restoration of the duplex, which was completed this year. You must use the duplex’s adjusted basis after the restoration to determine depreciation for the rest of the property’s recovery period. Figure the adjusted basis of the duplex as follows:

Note. Your basis in the land is its original cost of $5,000.

Easements. The amount you receive for granting an easement is generally considered to be proceeds from the sale of an interest in real property. It reduces the basis of the affected part of the property. If the amount received is more than the basis of the part of the property affected by the easement, reduce your basis in that part to zero and treat the excess as a recognized gain.

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

15-B Employer’s Tax Guide to Fringe Benefits

15-B Employer’s Tax Guide to Fringe Benefits 525 Taxable and Nontaxable Income

525 Taxable and Nontaxable Income 535 Business Expenses

535 Business Expenses 537 Installment Sales

537 Installment Sales 544 Sales and Other Dispositions of Assets

544 Sales and Other Dispositions of Assets 550 Investment Income and Expenses

550 Investment Income and Expenses 551 Basis of Assets

551 Basis of Assets 946 How To Depreciate Property

946 How To Depreciate Property