Aviation Labor Law

9

Aviation Labor Law

They are in violation of the law, and if they do not report for work within 48 hours, they have forfeited their jobs and will be terminated.

President Ronald Reagan,

responding to the PATCO strike, August 3, 1981

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should:

1. know what a labor union is and understand how one is formed;

2. recognize the difference between a “major dispute” and a “minor dispute” under the Railway Labor Act;

3. understand the distinction between mediation and arbitration;

4. understand the role of the federal government in both private and public sector labor disputes.

LABOR POLICY IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR

The Railway Labor Act

The Railway Labor Act governs the relationship between employers and employees in the airline industry.1 The Act is administered by a federal agency, the National Mediation Board, and was designed to balance three competing interests: (1) employees’ right to unionize; (2) employers’ desire to resolve labor disputes without strikes; and (3) the public’s interest in the uninterrupted flow of commerce. It achieves these goals by guaranteeing the rights of airline employees to unionize, by obligating employers and unions to bargain in good faith over the terms and conditions of employment, and by providing a mandatory mediation process before any work stoppage may commence.

The Railway Labor Act was a response to widespread labor unrest in the rail industry. Labor strikes including the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Pullman Strike of 1894 caused not only significant obstruction of commerce but also resulted in large-scale violence. During the 1877 strike, police and state militia fired on striking workers, killing dozens. The Pullman Strike also resulted in widespread bloodshed. Prior attempts to regulate labor–management relations were largely unsuccessful. The Arbitration Act of 1888 created a system of arbitration, but the federal government had no power to enforce the arbitration awards. The Newlands Act of 1913 created the Railway Labor Board, which was tasked with investigating and mediating labor disputes, but the Board was largely viewed as a corrupt arm of the railroad companies.

The Railway Labor Act was passed in 1926 to replace the previous system for regulating railway labor disputes. The Act favors negotiation and agreement between the parties instead of direct federal intervention. It promotes the mutually agreeable resolution of labor conflicts by prohibiting both employers and employees from engaging in strikes, lockouts, and other types of work stoppages without first following the negotiation process set forth in the Act.

How a Labor Union is Formed

A labor union is formed by a majority vote of the affected employees. The Railway Labor Act prohibits employers from interfering with employees’ right to organize and it flatly forbids “yellow dog” contracts, in which an employee must agree never to join a union as a condition of employment.

Once a union has been formed, the first order of business is to negotiate with the employer to reach a contract, called a collective bargaining agreement, regarding the terms and conditions of employment. Once the employer and the union negotiators have reached an agreement in principle, the contract is presented to the union’s members for a ratification vote.

Minor Disputes

Disagreements inevitably arise between employers and labor unions. These disagreements can be classified as either major disputes or minor disputes. A major dispute is one that concerns the formation or modification of the collective bargaining agreement. Minor disputes, on the other hand, involve isolated grievances that hinge on an interpretation of the existing agreement. The distinction is important because the two types of disputes are resolved in very different ways.

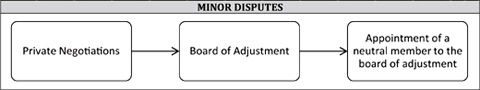

Minor disputes that cannot be resolved privately between the union and the employer are referred to a board of adjustment.2 The composition of the board is determined by the parties’ collective bargaining agreement. Generally, boards of adjustment are comprised of two representatives from the union and two representatives from management. If these four individuals reach a deadlock, either side may request that the National Mediation Board appoint a neutral referee. The decision of a board of adjustment is final and binding, and it can be enforced in the federal court.3

Figure 9.1 Minor disputes

It has not been possible to amend this figure for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472445629Figure9_1.pdf

The process by which minor disputes are resolved is shown in Figure 9.1 below. You will notice that labor strikes, lockouts, and other forms of self-help are not listed. This is because the Railway Labor Act prohibits self-help for minor disputes.

Major Disputes

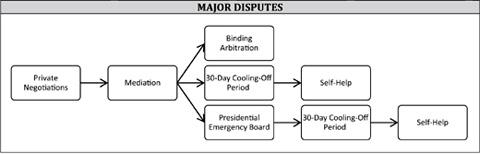

The first step to any major dispute is personal negotiation between the employer and the union. If negotiations fail, either party may submit the dispute to the National Mediation Board. Unlike judges, mediators do not have the power to issue rulings or declare one side victorious. Instead, the goal of a mediator is to help the parties reach a settlement. If no settlement is reached through the mediation process, there are three possible outcomes, as shown in Figure 9.2 below.

Figure 9.2 Major disputes

It has not been possible to amend this figure for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472445629Figure9_2.pdf

Option One: Binding Arbitration

The first option is binding arbitration. This option is only available if both parties agree to it. Arbitration is different from mediation. Unlike the mediation process, arbitration is an adjudicative process. The arbitrator will hear from both sides and will then make a ruling as to how the dispute must be resolved. The benefit of arbitration is that it is quick and definitive. The risk of arbitration is that both parties lose the option to craft a mutually agreeable solution to their dispute and must instead rely on the wisdom of a neutral third party to choose the outcome.

Option Two: The Cooling-Off Period

If the parties do not agree to submit the case to arbitration, the mediation board may initiate a 30-day “cooling-off” period. The parties can continue to negotiate amongst themselves to try and reach a settlement during this period. Once the 30 days is up, either party may engage in “self help.”

The Railway Labor Act does not list the permissible types of self-help that the union or employer may take, but the federal courts have generally refused to place limitations on the remedies available to either side after labor negotiations have broken down. For unions, self-help generally involves strikes and picketing activities. Employers can engage in their own form of self-help by conducting lockouts, hiring new employees to fill the vacancies created by striking workers, and imposing the employer’s last best contract offer on employees.

Option Three: Empanelment of a Presidential Emergency Board

In rare cases, the National Mediation Board may issue a recommendation to the President to empanel an emergency board to assist in resolving a labor dispute. The President may establish a Presidential Emergency Board (PEB) if the labor dispute threatens “to interrupt interstate commerce to a degree such as to deprive any section of the country of essential transportation service.” PEBs are convened by executive order and the President selects the members of the board. The PEB’s purpose is to investigate a labor dispute and issue recommendations to the parties.

While PEBs have the power to investigate and make recommendations, they ultimately cannot enforce those recommendations. All a PEB can do is assist the parties in reaching an agreed-upon compromise. This doesn’t mean that a PEB is powerless. Until the Board completes its investigation and issues its recommendations, the cooling-off period is extended. This allows the PEB to delay both sides’ ability to engage in strikes, lockouts, and other forms of self-help.