Asbestos firms and their liabilities

Chapter 6

Asbestos firms and their liabilities

Since the 1800s, asbestos firms have been key actors throughout the history of asbestos and have exercised a substantial influence in asbestos compensation. Firms have hired workers, withdrawn key medical information, lobbied governments, appeared in courts to defend themselves, relocated their business to escape liabilities, filed for bankruptcy, settled cases, set up voluntary compensation schemes, paid damages to asbestos victims—in most cases only after victims had been able to secure verdicts after extensive litigation. Many are the companies that played important roles at different times and in different countries. Most firms have abandoned the asbestos business or more simply disappeared because of bankruptcy or other forms of dissolution. Few of the companies that were in business a century ago have survived or are still connected to asbestos.

This chapter looks at three of these firms that were major players of the asbestos industry since the beginning of the twentieth century and are still in operation: James Hardie, Cape, and Eternit. For each firm, I outline their business model of each company and highlight some of the strategies that they implemented to avoid accountability for their asbestos liabilities. The chapter, which is a break from the country-by-country exposition of the material so far, enriches the data and the analysis with a transnational outlook—these three firms operated in different countries and litigation against them was brought in various jurisdictions—on asbestos compensation as a set of cultural responses to the dark side of industrialization. The stories of the three firms raise important issues of the role of corporate law. In particular, the chapter highlights how adherence to two bedrock principles of corporate law (the limited liability of shareholders and the doctrine of separate and distinct corporate entity) enabled firms to postpone, limit, and even avoid, facing their asbestos liabilities and how victims engaged in legal struggles in which they found themselves catching up with powerful adversaries’ use of corporate law to escape the rule of law.

James Hardie’s Machiavellian corporate restructuring

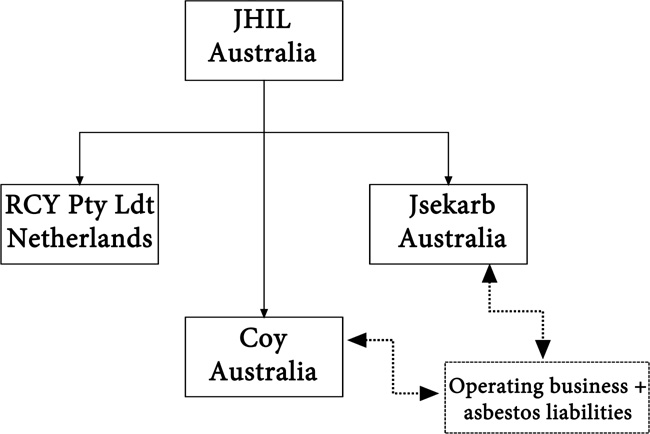

In Australia, James Hardie is synonymous with asbestos. A leader in fiber cement building products with operations in Australia, the United States, New Zealand, Indonesia, Chile, and the Philippines, James Hardie mined, manufactured and distributed the majority of Australian asbestos thus dominating the domestic asbestos industry for decades. The firm assumed the parent/subsidiary structure in the 1930s. James Hardie Industries Limited (JHIL) held all of the shares of two subsidiaries, James Hardie and Company Pty Limited (Coy) and Jsekarb Pty Limited (Jsekarb), which run the operations of the business. Coy manufactured fiber cement building products and asbestos-cement pipes and Jsekarb manufactured brake linings for motor vehicles, railway wagons and locomotives.1 The company reached the peak of its growth by the mid-1950s when “more than half of the new homes built in New South Wales were made from Hardie’s asbestos-cement sheets.”2

Since its business generated significant asbestos liabilities, Hardie began being targeted by lawsuits in the 1970s. In a matter of a few years, Hardie realized the magnitude of its asbestos liabilities and began enacting stratagems to avoid accountability. The first stratagem involved settling cases of union members for small amounts. This, in 1979, Hardie and the Federated Miscellaneous Workers Union agreed that any Hardie employee who was diagnosed with an asbestos disease recognized by the Dust Disease Board of New South Wales would receive an out-of-court lump sum award of AUD 14,000.3 The stratagem however was ineffective. Rather than turning off victims, the agreement invited victims to come forward. Asbestos lawsuits increased dramatically and, from 1981 to 2000, James Hardie paid out over AUD 130m to more than 2,000 asbestos victims. This wave of cases led Hardie to enact a second stratagem involving a substantial amount of conglomerate restructuring. This stratagem effectively shielded Hardie from asbestos liabilities for a decade.

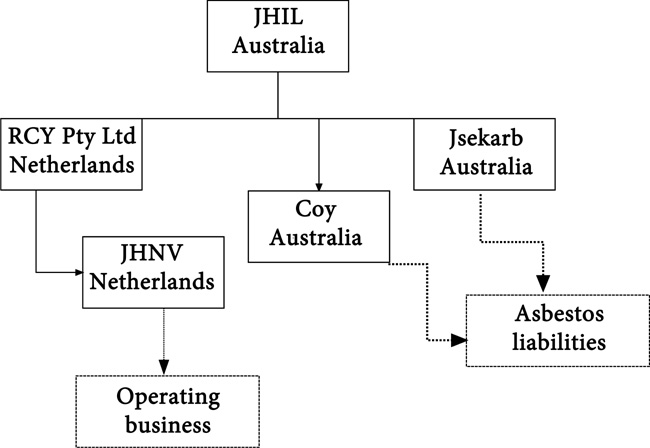

The stratagem was put to work in 1996 and consisted of four stages. The first stage (1996-2001) strategy entailed modifying the existing conglomerate structure by transferring the lucrative operating business (that is, all non-asbestos assets of Coy and Jsekarb) to James Hardie NV (JHNV), a subsidiary of RCI Pty Limited, a Dutch company that was fully owned by JHIL (see Figures 6.1 and 6.2).

At the end of this stage, JHIL, which retained all shares in the two subsidiaries, owned two empty boxes soaked in asbestos liability.

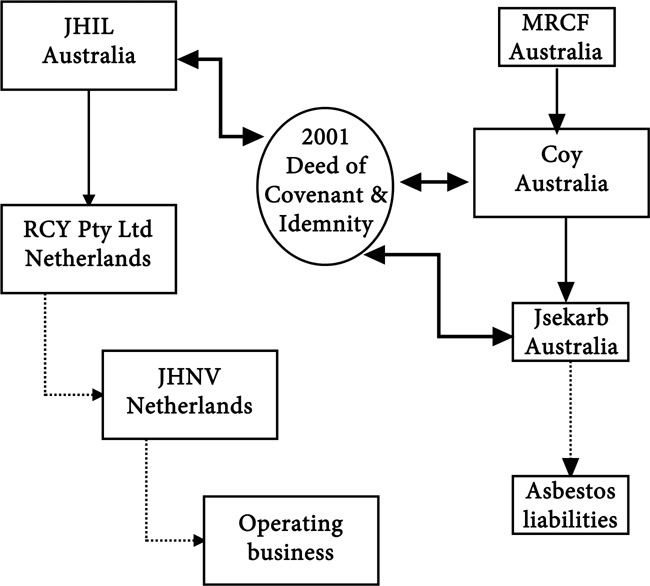

The second stage (February 2001) entailed Jsekarb becoming a subsidiary of Coy and Coy’s, shares being transferred to the Medical Research and Compensation Foundation (MRCF), a charitable trust set up for the purpose of conducting research on asbestos toxicity and compensating asbestos victims (see Figures 6.3). Later, Coy and Jsekarb were respectively renamed Amaca Pty Ltd and Amaba Pty Ltd. The second stage only entailed the signing of the 2001 Deed of Covenant and Indemnity, an agreement between Coy, Jsekarb, and JHIL under which “JHIL undertook to make payments totaling AUD 112.5m over 42 years in return for an indemnity and covenant not to sue in relation to certain asbestos claims and intercompany transactions.”4 As a result, the operating business and asbestos liability were separated into different corporate entities: the asbestos liabilities went to MRCF and the operating businesses stayed with the James Hardie group.

Figure 6.1 James Hardie (pre-1996)

Figure 6.2 James Hardie (1996-2000)

Figure 6.3 James Hardie (February 2001)

The third stage (October 2001) entailed rearranging the parent/subsidiary structures within the James Hardie group (see Figures 6.4). To do so, the Dutch company RCI Pty Limited was renamed James Hardie Industries NV (JHINV) and became a subsidiary of JHIL. Its shares in JHNV—the company that held all operating businesses—however were transferred to JHIL. At this point, JHINV became the parent company of the conglomerate, holding, amongst others, all shares in two subsidiaries: JHIL and JHNV.

Figure 6.4 James Hardie (October 2001)

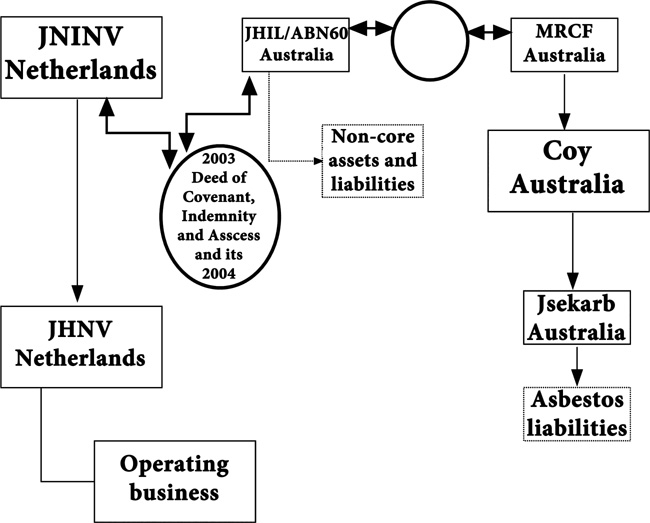

This meant that AUD 1.9b left Australia for Europe. The small European state had not been chosen randomly: at the time, the Netherlands was one of the few countries around the world that had not signed a treaty for the enforcement of judicial orders with Australia. The fourth and final stage (2003-2004) entailed changing JHIL’s name into ABN 60 Pty Ltd (ABN60) and separating it from the (now Dutch-based) James Hardie group (see Figures 6.5).

ABN60 cancelled all shares held in it by JHINV. As a result, ABN 60 became a wholly owned subsidiary of ABN 60 Foundation Pty Limited and ceased to be a member of the James Hardie Group. Immediately prior to the cancellation of shares, ABN 60 entered into a Deed of Covenant, Indemnity and Access with JHINV. The combined reading of the 2003 Deed of Covenant, Indemnity and Access and its 2004 Rectification stipulate that ABN60, which has negligible assets, renounces its right to be indemnified for asbestos claims by JHINV. The legal picture that emerges from the conglomerate restructuring is both frightening and depressing: what was once the parent company of subsidiaries that had dealt in asbestos for more than half a century became a company estranged from the conglomerate, with no operating business, and negligible assets. The four-stage Machiavellian exit strategy left victims with no remedy against a profitable conglomerate that had generated a substantial amount of unmet asbestos liabilities.

Figure 6.5 James Hardie (2003-2004)

The Machiavellian plan, however, did not go unchallenged. In reaction to such grim prospects of recovery, unions and asbestos victim advocacy groups organized public protests and a successful boycott of James Hardie products in 2004.5 By May of 2005, James Hardie had lost 2 percent in annual net profit as a consequence of the boycott.6 The loss exceeded AUD 1b.7 The protests and boycotts also found allies in the political world. The State of New South Wales established a Commission of Inquiry with the mandate to look into MRCF and the circumstances “in which MRCF was separated from the James Hardie Group and whether this may have resulted in or contributed to a possible insufficiency of assets to meet its future asbestos-related liabilities … and the adequacy of current arrangements available to MRCF under the Corporations Act.”8 The inquiry concluded that James Hardie had engaged in deceptive conduct that misled the stock exchange to understate the extent of future asbestos liabilities. This finding was reinforced in 2012 when the High Court of Australia upheld the conviction of seven Hardie directors, including the former chairman Meredith Hellicar, for making misleading statements, and thus breaching their duties as directors, when in 2001 they shifted the company to the Netherlands with the promise that they had formed a “fully funded” body to meet all future compensation claims.9 As the inquiry had already established, the Fund was far from being fully funded: “Within three years, the compensation fund cupboard was empty, short by an estimated $1.5 billion.”10

The inquiry however left James Hardie with few options. In 2006, the conglomerate negotiated the establishment of a new, more generously funded charitable trust with the government of New South Wales. This trust, called the Asbestos Injuries Compensation Fund (AICF), is a public-private partnership between James Hardie and the NSW government and its terms mandated that, after an initial deposit of AUD 184,000, James Hardie would fund it for 40 years with a yearly sum drawn from up to 35 percent of the company’s annual cash flow.11 In 2009, AICF reported that all personal injury claims caused by exposure to asbestos in Australia “in respect of which final judgment has been give against, or a binding settlement has been entered into by [any company of the James Hardie group]” were being paid.12 Compensation was further guaranteed against corporate stratagems to avoid liability by the provision that events such as bankruptcy and restructuring of the holding company, which is the signatory of the trust deed, would have no effect as to James Hardie’s obligation to the Fund.

In 2009, however, James Hardie’s willingness to stick to its obligation was tested as the global economic crisis weakened its commitment financially to support the Fund. The collapse of the housing market in the United States, with the resulting collapse of orders in the homebuilding industry, dried up cash flow, and in April 2009 the company made public statements warning that it was unlikely to contribute to the Fund: “With assets of just AUD 140m at the end of March, the fund says it may be unable to meet all of its commitments within two years.”13 Fortunately for asbestos victims, in 2012 Hardie received a generous tax refund in the amount of AUD 369.8 million, 35 percent of which was directed to the AICF.14 This influx of money replenished the pockets of the Fund, which in the nine months to December 31, 2011 paid out AUD 73.9 million in compensation.15 In 2011, Hardie relocated one more time, moving its domicile to Ireland allegedly for reasons having to do with taxes and management.16 Overall the establishment of the Fund is certainly good news for Australian asbestos victims: it is an achievement that was obtained in spite of corporate law.

Cape’s successful exit strategy from the American asbestos litigation

Registered in England and Wales, Cape plc is the holding company of a network of subsidiaries that do business in the UK, North Africa, the Middle East and the Far East. Currently this conglomerate specializes in insulation, fire protection, abrasive blasting, refractory, coatings, cleaning, training and other essential non-mechanical services. While its current business is not connected to its asbestos heritage, Cape used to be a leading asbestos firm. The firm was founded in 1893 to control a syndicate that operated South African crocidolite asbestos mines and then expanded to manufacture insulation products containing asbestos. It mined most of the world’s amosite asbestos and was a leading producer of crocidolite. Its manufacturing and sales expansion reached its peak after World War II with operations in the UK, the United States, South Africa, France, Germany, and Italy. While the business reach and asbestos liabilities of Cape are global, in this chapter I only focus on corporate restructuring that was implemented by Cape headquarters as exit strategy with regard to asbestos liabilities in the United States.

Cape has done business in the United States since the 1930s. It sold its asbestos to various clients through the Union Asbestos and Rubber Company (UNARCO), which was the exclusive distributor of Cape’s asbestos in North America. As a consequence of the success of this business venture, the London headquarters decided, in 1953, to establish a fully-owned subsidiary in Chicago: the North American Asbestos Corporation (NAAC). For several decades, NAAC successfully acted as an “agent” of CASAP, which was based in South Africa and fully owned by Cape, and which in turn fully owned Egnep, another South African part of Cape’s conglomerate that ran the mining business. NAAC acted with no authority to bind CASAP contractually and received commission for its service (see Figures 6.6).

Figure 6.6 Cape (pre-2005)

Between 1953 and the late 1970s, Cape sold “nearly half-a-million tons of asbestos in the United States.”17