Airport Zoning and Noise

10

Airport Zoning and Noise

In interpreting and applying the provisions of this resolution, they shall be held to be the minimum requirements adopted for the promotion of the public health, safety, comfort, convenience and general welfare.

1916 New York Zoning Resolution

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, you should:

1. understand how zoning authority is exercised;

2. understand the concepts of conforming and nonconforming use;

3. understand the benefits of noise exposure mapping to airport operators;

4. be familiar with the various tools that an airport operator may use as part of a noise abatement program;

5. be familiar with the criteria that the FAA uses to evaluate a proposed noise abatement program;

6. be familiar with aircraft noise stages.

AIRPORT ZONING

Overview of Zoning Laws

Prior to zoning, cities had to rely on nuisance laws to curtail hazardous or obnoxious activities within the city proper, such as brick manufacturing (Hadacheck v. Sebastian, 239 U.S. 394 (1915)), beer brewing (Mugler v. Kansas, 123 U.S. 623 (1887)), and coal mining (Vogler v. Chicago & Carterville Coal Co., 180 Ill. App. 51 (Ill. App. 1913)). New York City enacted the first zoning ordinance in 1916. The ordinance was basic but effective. It created setback requirements, limited the number of tall buildings that could be built in a given area, imposed height limitations, and established zones for certain industries.

Because of the success of the New York City zoning ordinance, Commerce Secretary (and future President) Herbert Hoover established a zoning commission to develop a uniform zoning act that could be adopted by local governments. The result was the basis for modern zoning policy, the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act. State statutes based on the Standard State Zoning Enabling Act were immediately challenged in court, but their basic constitutionality was upheld by the US Supreme Court in Village of Euclid v. Amber Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926). However, this isn’t to say that all zoning ordinances are constitutional or that every application of zoning power is legitimate.

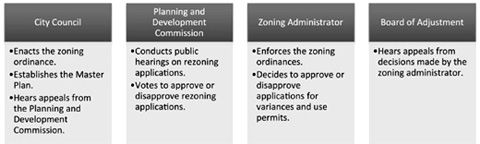

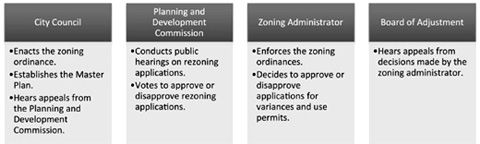

Figure 10.1 Apportionment of zoning authority between the city council, planning and development commission, zoning administrator, and the board of adjustment

It has not been possible to amend this figure for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472445629Figure10_1.pdf

Zoning authority is delegated to quasi-judicial government bodies. In a typical scenario, the city council is responsible for enacting the zoning ordinance. A commission, generally called a planning and development commission, is responsible for conducting public hearings and deciding whether to approve applications to rezone land. A Zoning Administrator is responsible for enforcing the zoning ordinances and deciding whether to approve applications for variances or permits. A board, typically called a board of adjustment, reviews the decisions of the zoning administrator.

Euclidian Zoning

Euclidian zoning (named after Euclid v. Amber Realty) uses cumulative zoning. Under this system, areas are zoned for multiple purposes, such as height, area, and use. In the Euclid case, the use category contained six different subcategories of uses: U-1 included things such as single family dwellings, parks, and water towers; U-2 included things such as two-family dwellings; U-3 included apartments, hotels, schools, libraries, hospitals, and similar types of uses; U-4 included retail stores; U-5 included light manufacturing; and U-6 included water reclamation, cemeteries, garbage dumps, and other such uses. With cumulative zoning, a permitted use can include not only the uses in that category but also all uses below it. For example, a parcel of land zoned as U-3 could include all the permitted uses in zones U-3, U-2, and U-1.

Euclidian zoning also makes use of master plans (sometimes called “comprehensive plans”) in which zoning is established before land is developed, so that a town’s expansion can be theoretically planned in advance. Many municipalities have found this approach unworkable because it is difficult to predict how a city will expand. As a result, many municipalities’ master plans zone undeveloped land in the most restrictive zoning category. This creates a wait-and-see approach in which land developers must apply to have property rezoned before beginning development. This places the burden on developers to demonstrate that their intended plans support the public good.

Compatible Uses Around Airport

Land development in the areas surrounding an airport can interfere with airport operations. In order to aid communities that desire to restrict building height and use in the area around an airport, the FAA has published Advisory Circular 150/5190-4A, A Model Zoning Ordinance to Limit Height of Objects Around Airports. The Advisory Circular states:

Aviation safety requires a minimum clear space (or buffer) between operating aircraft and other objects. When these other objects are structures (such as buildings), the buffer may be achieved by limiting aircraft operations, by limiting the location and height of these objects, or, by a combination of these factors … The purpose of zoning to limit the height of objects in the vicinity of airports is to prevent their interference with the safe and efficient operations of the airport.

The model zoning ordinance establishes several distinct zones around the airport, and within each zone, height limitations apply. The model zoning ordinance also contains use restrictions within the airport zone. Regardless of height, no device or structure may be placed on land within the airport zone if it creates an electrical interference with navigation signals or radio communications, makes it difficult for pilots to distinguish between airport lights and non-airport lighting, impairs pilot visibility, creates a bird hazard, or risks interfering with landing, takeoff, or maneuverability of aircraft.

The model zoning ordinance also contains procedures regarding nonconforming uses. A nonconforming structure is one that is not permitted under the zoning ordinance, but is nonetheless permitted to remain in place. There are many ways in which a property could be authorized to continue with a nonconforming use. For example, if the property was in its current use before the zoning ordinance was put in place and the zoning ordinance does not contain a provision that applies the ordinance retroactively, it will be grandfathered in as a nonconforming use. Depending on how the zoning ordinance is written, property owners may also have the option to apply for a use variance to permit a nonconforming structure or use on their property. The model zoning ordinance requires landowners with nonconforming property to allow airport authorities to enter onto their land to inspect potential hazards and install lighting or other appropriate warnings to alert pilots to potential hazards created by the nonconforming use. The model ordinance also permits landowners to apply for a variance.

Several states have passed laws authorizing municipalities to adopt airport zoning ordinances. The following case concerns one of those statutes.

Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

FACTS: Pennsylvania passed the Airport Zoning Act in 1984. The Act did not impose a specific zoning policy upon the cities with the State of Pennsylvania but instead gave those cities authority to promulgate their own individual zoning ordinances. The Act states:

In order to prevent the creation or establishment of airport hazards, every municipality having an airport hazard area within its territorial limits shall adopt, administer and enforce … airport zoning regulations for such airport hazard area. The regulations may divide the area into zones and, within the zones, specify the land uses permitted and regulate and restrict the height to which structures may be erected or objects of natural growth may be allowed to grow. A municipality that includes an airport hazard area created by the location of a public airport is required to adopt, administer and enforce zoning ordinances pursuant to this subchapter if the existing comprehensive zoning ordinance for the municipality does not [already regulate structure height and land use in the hazard area].

Chanceford Aviation Properties owned a public airport in the Chanceford Township. Its predecessor had repeatedly demanded that the Chanceford Township Board of Supervisors enact airport zoning regulations pursuant to the statute. The Board of Supervisors declined, stating that it already had a zoning ordinance that incorporated FAA standards regarding height obstructions. The predecessor filed suit and Chanceford Aviation Properties was substituted for the plaintiff when it purchased the airport. The trial court sided with the airport, but the Court of Appeals reversed the decision. The airport then appealed to the state Supreme Court. There were two issues on appeal: (1) are all municipalities containing an airport required to enact airport zoning ordinances?; and (2) if airport zoning ordinances are necessary, does the Chanceford Township ordinances comply with the state statute?

REASONING: The state Supreme Court concluded that airport zoning is mandatory in every municipality where an airport is located. The first sentence of the Pennsylvania statute uses the imperative term shall: “In order to prevent the creation or establishment of airport hazards, every municipality having an airport hazard area within its territorial limits shall adopt, administer and enforce … airport zoning regulations.” This sentence clearly requires every municipality containing an airport to enact and enforce proper zoning ordinances to guard against obstructions and hazards.

The state Supreme Court also held that Chanceford Township’s existing zoning ordinances failed to comply with the state statute. The second sentence of the statute uses the permissive term may: “The regulations may divide the area into zones and, within the zones, specify the land uses permitted and regulate and restrict the height to which structures may be erected or objects of natural growth may be allowed to grow.” This clause allows each municipality to determine how best to regulate airport hazards, but the regulations must still meet the requirement of the statute to impose height and use restrictions in the areas surrounding an airport. Chanceford Township’s zoning ordinance was too basic. It established some height limitations on the approach to the airport, but it contained no use restrictions. Moreover, the zoning ordinance’s height restrictions only applied to the airport, not to the surrounding properties. The state Supreme Court found that this was clearly inadequate to satisfy the statutory requirement to regulate airport hazards.

HOLDING: The Pennsylvania statute made it mandatory for every municipality containing an airport to enact zoning ordinances to curtail airport hazards. The Chanceford Township ordinance did not comply with the state statute because it only imposed height limitations on the airport itself, not on the surrounding properties. It also failed to contain any use restrictions. For these reasons, the ruling of the Court of Appeals was reversed.

Federal Regulation of Airport Hazards

Federal Air Rule Part 77 regulates air hazards. It applies to structures, construction, terrain, trees, and equipment. Part 77 requires prior notice to the FAA before construction can begin within the following distances from an airport or heliport:

• At any distance from an airport, if the proposed construction is over 200 feet above ground level.

• Within 20,000 feet of a military airport or public airport that has a runway greater than 3,200 feet in length, if the proposed construction exceeds a height that is equal to or greater than 1/100th of the distance from the runway.

• Within 10,000 feet of a military airport or public airport that has a runway equal to or less than 3,200 feet in length, if the proposed construction exceeds a height that is equal to or greater than 1/50th of the distance from the runway.

• Within 5,000 feet of a public heliport, if the proposed construction exceeds a height of 1/25th of the distance from the landing pad.

When the FAA receives the notice, it may issue a “no hazard” finding or conduct an aeronautical study of the effect of the proposed construction. Such studies are conducted by the Office of the Regional Manager, Air Traffic Division. The Air Traffic Manager may solicit comments from any interested parties, examine possible revisions to the proposed construction, make recommendations to adjust aviation requirements to accommodate the construction, and conduct public hearings on the effect of the proposed construction. If a public hearing is set, the FAA will designate a hearing officer to issue subpoenas, administer oaths, hear testimony, and receive evidence. The hearing officer then submits the transcripts of the hearing and the evidence to the FAA Administrator for a decision.

THE CONDEMNATION POWER

Source of the Condemnation Power

Eminent domain, or condemnation, is an inherent governmental power to seize private property and convert it to public use. In the aviation context, condemnation is often used to seize land near airports in order to construct airport facilities, demolish hazards, or protect against potential damage to private property by airport operations. The Fifth Amendment limits condemnation in three ways. It states: