Ad Hoc References and Adjudications Outside the Act

AD HOC REFERENCES AND ADJUDICATIONS OUTSIDE THE ACT

No Conferral of Jurisdiction where Continued Jurisdiction Objection | |

(1)Ad Hoc References to Adjudications

5.01 The statutory right to adjudicate arises1 only in respect of construction contracts within the meaning of ss. 104 and 105 of the Act.2 Contracts not caught by the legislation may nevertheless contain an adjudication clause thus providing either contracting party with a right to adjudicate. Where neither situation applies and there is no pre-existing right to adjudicate, an adjudicator may be appointed to decide a dispute or an issue on the basis of a one-off agreement to adjudicate. Such agreements may be referred to as ‘ad hoc’ adjudications as the expression ‘ad hoc’ generally signifies a solution that has been custom designed for a specific problem. The situations in which the parties may expressly or impliedly confer ad hoc jurisdiction on an adjudicator are discussed in this chapter.

5.02 In the context of arbitration it is well established that the parties may agree to confer jurisdiction upon an arbitrator on an ad hoc basis.3 In principle, if two people agree to submit a dispute to a third person for determination then the parties are conferring jurisdiction on that third party to decide the matter and are agreeing to be bound by his decision: Westminster Chemicals & Produce Ltd v Eicholz & Loeser (1954),4 Project Consultancy Group v The Trustees of the Gray’s Trust (1999) (Key Case).5 The agreement to confer special jurisdiction on an adjudicator may be express but it may also be implied from the conduct of the parties.

5.03 If one party considers that an issue or dispute is outside the agreement to adjudicate, or the scope of the reference, he may protest there is no jurisdiction to determine that matter. If he protests in a form that indicates he will not abide by the decision of the adjudicator on that matter, he may continue to take part in the adjudication without losing his right to argue the decision is not binding because it was made without jurisdiction.

5.04 Where the responding party does not wish to confer ad hoc jurisdiction on the adjudicator, the objection to jurisdiction ought to be taken at the earliest opportunity or there will be a real prospect that the responding party will be found to have waived the lack of jurisdiction and acquiesced in conferring ad hoc jurisdiction on the adjudicator.6

5.05 Typical situations in which the issue of ad hoc jurisdiction arises are where the referring party asks an adjudicator to determine a claim and:

1. An adjudication agreement exists but is not wide enough to cover the claim referred.

2. An adjudication agreement exists wide enough to cover the claim in question but one party asks for an issue to be decided which was not part of the original reference.

3. No adjudication agreement exists and there is no statutory right to adjudicate.

5.06 Whether the parties have conferred ad hoc jurisdiction on an adjudicator is a question of fact. An ad hoc submission may occur in a number of situations.

Express Agreements to Confer Jurisdiction

5.07 Conferring ad hoc jurisdiction on an adjudicator may be done expressly by agreement as was the case in Nordot Engineering Services Ltd v Siemens plc (2001).7 The issue concerned whether the works were ‘construction operations’ under the Act. The respondent argued they were not but also said ‘we will, however, abide by your decision in this matter and will comply with what ever direction you deem appropriate’. This was a clear and unequivocal agreement to be bound by the decision of the adjudicator that conferred jurisdiction to decide the jurisdiction question.

Implied Agreements to Confer Jurisdiction

5.08 For there to be an implied agreement to give the adjudicator jurisdiction over a dispute or a particular issue, one needs to look at everything material that was done and said to determine whether one can conclude that the parties must be taken to have agreed that the adjudicator had such jurisdiction. Conferral of jurisdiction has been implied from the circumstances in the following cases:

(1) In Northern Developments (Cumbria) Ltd v J&J Nichol (2000)8 the respondent raised several grounds for challenging the validity of the decision, including that the adjudicator had no power to decide costs. On the issue of costs it was shown that both parties’ submissions had asked the adjudicator for costs and neither had denied there was a power to deal with costs. Hence neither party had contended there was no jurisdiction to deal with costs. The judge found that it was implied from the facts that the parties had agreed the adjudicator had the authority to determine costs and hence they had conferred jurisdiction on the adjudicator to decide the issue.

(2) In Carillion Construction Ltd v Devonport Royal Dockyard (2005)9 the referring party had asked for interest to be decided and the respondent had answered by saying the question of interest did not arise as no sum was due. The respondent did not argue that there was no jurisdiction to deal with interest. The Court of Appeal found that this amounted to acquiescence by the respondent in the conferral of ad hoc jurisdiction to make a decision about the claim to interest.

(3) Maymac Environmental Services Ltd v Faraday Building Services Ltd (2001)10 concerned a dispute as to whether a relevant construction contract existed. The court found there was a construction contract and that there had been an agreement to adjudicate on the same terms. It was held that the respondent would be estopped by representation from asserting that there was no jurisdiction.

Objecting and Reserving the Right to Object

5.09 There will be no implied agreement if at any material stage before or during the adjudication a clear objection is raised by the party contesting jurisdiction of the adjudicator, coupled with a reservation of the right to maintain that objection. A party that does not wish to give the adjudicator power to decide a matter needs to raise the jurisdiction objection at the earliest opportunity. The objecting party may ask the adjudicator to enquire into the jurisdiction issue and to decide that there is none and that he or she should resign.

5.10 An adjudicator does not have power to give a binding decision upon his or her own jurisdiction unless the parties confer that power.11 A decision of an adjudicator about the existence or scope of his or her own jurisdiction is therefore, in principle, a non-binding decision.12 However, when raising a jurisdiction objection and asking the adjudicator to consider it, it is important that the objecting party does not give the adjudicator power to decide the jurisdiction issue in a binding way. Accordingly a party must reserve the right to maintain its jurisdiction objection at a later date. In the absence of an express reservation the court may find by implication that the party has permitted the adjudicator to make a binding decision on the issue: Christiani & Neilsen Ltd v Lowry Centre Development Co. Ltd (2000).13 It is essential therefore that the objecting party makes it clear that, despite asking for the jurisdiction to be investigated, they do not agree to give the adjudicator power to make a binding decision either on the jurisdiction point or on the substantive dispute.14

5.11 Where an effective reservation of rights has been made the objecting party may continue to participate in the adjudication and yet still argue that any decision is unenforceable because it was made without jurisdiction: Project Consultancy Group v The Trustees of the Gray’s Trust (1999) (Key Case).15

5.12 A clear reservation can be made by words expressed by or on behalf of the objecting party. Words such as ‘I do not intend to confer on the adjudicator jurisdiction to make a binding decision, I am only participating in the adjudication under protest and reserve the right to argue that any decision was made without jurisdiction’ will usually suffice to make an effective reservation. One can, however, look at every relevant thing said and done during the course of the adjudication to see whether by words and conduct what was clearly intended was a reservation as to the jurisdiction of the adjudicator: Aedifice Partnership Ltd v Ashwin Shah (2010) (Key Case).16

5.13 If a party does not reserve its position effectively then generally it cannot avoid enforcement on the ground that it was made without jurisdiction. There may be unusual circumstances if the party making the challenge did not know or could not reasonably have ascertained the grounds of challenge before the decision was issued.17 However where a party knows or should have known of grounds for a jurisdictional objection and participates in the adjudication without making an effective reservation then it may be said that it has submitted to the jurisdiction or waived the right to object.18

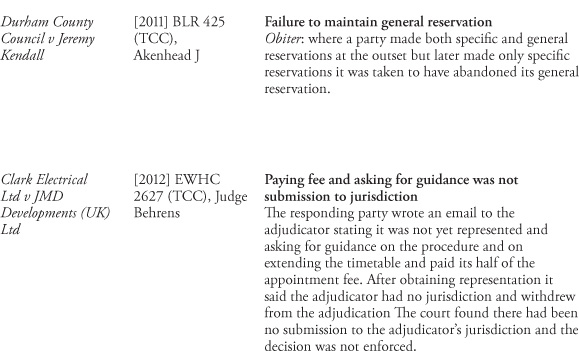

No Conferral of Jurisdiction where Continued Jurisdiction Objection

5.14 Whether the parties have agreed that the adjudicator could determine his own jurisdiction is a matter of fact. In Christiani & Nielsen Ltd v The Lowry Centre Development Co. Ltd (2000)19 the respondent agreed to make submissions on the existence of a construction contract. That was found to be simply an agreement as to procedure. The respondent’s submissions were made against the background of their continuing protest as to jurisdiction. Thus the judge decided that the respondent was not agreeing that the adjudicator could make a binding decision on jurisdiction.

5.15 A party will not be taken to have submitted to the jurisdiction of an adjudicator unless he knew of the matters which meant the adjudicator lacked jurisdiction: R. Durtnell & Sons Ltd v Kaduna Ltd (2003).20 However, the court will consider whether a party actually knew or ought to have known that there was a jurisdiction issue to be made: Aedifice Partnership Ltd v Ashwin Shah (2010) (Key Case).21

General Reservations

5.16 Generally a party who wishes to do so may object to the jurisdiction of the adjudicator either in general terms or by objecting to jurisdiction in relation to a specific matter.22 However where the general reservation was used a party had to be careful to ensure it was clearly worded to ensure it achieved its purpose. Where both a general and specific reservation is made at the outset but later only the specific reservation is argued, a party may be taken to have abandoned the general reservation.23