Empiricists, rationalists and the Enlightenment

Empiricists, Rationalists and the Enlightenment

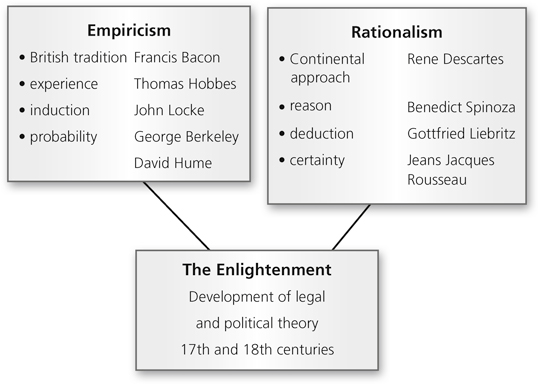

3.1 Empiricists

3.1.1 British Tradition

1. Influenced by the Renaissance, philosophers tended to focus on human nature and the law of nature, but not in the same ways that classical and medieval thinkers had done.

3. Interest grew in discoveries and the advancement of material science, with increased knowledge of physics, astronomy and mathematics, a seminal English influence being Sir Isaac Newton (1642–1727).

4. The resulting scientific advances had a considerable methodological effect on legal philosophy, with much of the emphasis being redirected to collection of empirical data on the premise that, if it produced such exciting results for pure science, it could also be adapted to develop the social philosophical science of jurisprudence.

5. The idea was that it is not the soul that provides the explanation of how mankind functions, but a constantly changing and developing collection of perceptions flashing across the brain, linked to some kind of association with the mind, an early anticipation of psychology.

6. These were all influences that took strong root in Britain, the methodology to be used being empiricist, and its main characteristics and key words being:

(a) experience

(b) induction

(c) probability.

7. Important British empiricists included:

Francis Bacon (1561–1626), whose Novum Organum Scientiarum (1620) is an exposition of the inductive method of interpreting nature

Francis Bacon (1561–1626), whose Novum Organum Scientiarum (1620) is an exposition of the inductive method of interpreting nature

Thomas Hobbes (1561–1626), who is usually remembered for describing Man’s existence as ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’ (section 3.1.2)

Thomas Hobbes (1561–1626), who is usually remembered for describing Man’s existence as ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’ (section 3.1.2)

John Locke (1632–1704), whose best-known work is entitled An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) but who also wrote influentially on government and rights

John Locke (1632–1704), whose best-known work is entitled An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) but who also wrote influentially on government and rights

George Berkeley (1685–1753), whose views changed considerably during his lifetime, but who ended up believing that the only realities were God, the soul and ideas in the human mind

George Berkeley (1685–1753), whose views changed considerably during his lifetime, but who ended up believing that the only realities were God, the soul and ideas in the human mind

David Hume (1711–76), who wrote A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40) explaining that all ideas are derived from sense impression, which he called the phenomena or appearances of things reflected in the senses (section 3.1.4).

David Hume (1711–76), who wrote A Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40) explaining that all ideas are derived from sense impression, which he called the phenomena or appearances of things reflected in the senses (section 3.1.4).

3.1.2 Hobbes

1. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was a philosopher whose view of life as a pessimistic writer was coloured by a number of things as he:

was born in the same year as the Spanish Armada attempted to conquer England

was born in the same year as the Spanish Armada attempted to conquer England

lived through mostly depressing times, including the English Civil War

lived through mostly depressing times, including the English Civil War

died in extreme old age.

died in extreme old age.

2. Influenced by Galileo’s ideas on perpetual motion, he originally intended to write a comprehensive account of science, men and citizens, but was obliged to flee to the continent because of his political views.

3. Eventually he published his important work Leviathan (1651), expanding on an earlier work De Cive (Concerning the Citizen) (1642), in which he argued that:

(a) Man is selfish, self-interested and pursues his own good at the expense of others

(b) such unenlightened self-interest pursued in ignorance would lead to disaster

(c) society in a state of nature would negate any possibility of civil order or rule of law

(d) given these characteristics of human existence, Man’s life would inevitably be ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’, and a ‘war of every man against every man’.

4. However, there are some positive counter-balances, including the fact that:

(a) people possess a right of nature, i.e. a wish to survive

(b) they have a degree of rationality, or law of nature

(c) the right of survival at all costs that justifies a person’s violence has to be renounced in order to achieve mutual security

(d) this leads to a rough state of uncomfortable balance in society.

(a) an absolute monarch, or

(b) a democratic parliament.

6. The Leviathan is given absolute power in return for securing peace and stability for its citizens, so if power is the sole element that legitimates the law:

(a) it is the act of rebellion that is wrong rather than supporting one form of government or another

(b) values such as justice, morality, freedom and property have no universal or eternal meaning, being dependent upon the policy of Leviathan

(c) the state is always right as long as it is achieving its primary objectives of stability and maintenance of peace.

7. His discussion of what he identifies as the 19 laws of nature can be distilled to the following basic rules:

(a) men should strive to keep the peace

(b) they should be prepared to give up much of their right of nature in return for protection

(c) generally they should follow the golden rule of ‘do as you would be done by’.

8. In summary, Hobbes’ philosophy contains:

aspects of natural law

aspects of natural law

social contractarian elements

social contractarian elements

some of the ideas of legal positivism, in a disregard of the need for morality, freedom, justice etc.

some of the ideas of legal positivism, in a disregard of the need for morality, freedom, justice etc.

suggestions of utilitarian hedonism

suggestions of utilitarian hedonism

perhaps most of all, and explanatory of the others, pragmatic responses to contemporary difficulties, or an early form of realism

perhaps most of all, and explanatory of the others, pragmatic responses to contemporary difficulties, or an early form of realism

a counter-balance to more optimistic traditions of legal thinking

a counter-balance to more optimistic traditions of legal thinking

an argumentative inclination to enter into philosophical disputes, reminiscent of HLA Hart in the 20th century.

an argumentative inclination to enter into philosophical disputes, reminiscent of HLA Hart in the 20th century.

3.1.3 Locke

1. John Locke (1632–1704) led a varied earlier life, mixing the occasional practice of medicine and involvement in political intrigues with experimental science and travel, obtaining extensive political experience working for the Earl of Shaftesbury followed by high administrative offices, and so developing his interest in government.

2. Major key points in his natural rights philosophy are:

(a) the existence of a benign state of nature, but without organisation