Charitable Trusts

Charitable trusts

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ appreciate the privileges enjoyed by charitable trusts

■ define a charity within the new Charities Act 2011

■ recognise a charitable purpose within the Charities Act 2011

■ understand the cy-près doctrine

12.1 Introduction

A charitable trust is a type of purpose trust in that it promotes a purpose and does not primarily benefit specific individuals. However, in furthering a purpose the performance of the trust may result in individuals or members of the public deriving direct benefits. Even so, the trust remains one for a purpose and not for the benefit of those individuals. The purpose of the trust is to benefit society as a whole or a sufficiently large section of the community so that it may be considered public. Thus, a charitable trust is a public purpose trust and is enforceable by the Attorney General on behalf of the Crown.

Private trusts, on the other hand, seek to benefit defined persons or narrower sections of society than charitable trusts and, as we saw, a private purpose trust is void for lack of a person to enforce the trust.

Generally, charitable trusts are subject to the same rules as private trusts but, as a result of the public nature of such bodies, they enjoy a number of advantages over private trusts in respect of:

(a) certainty of objects;

(b) the perpetuity rule;

(c) the cy-près rule; and

(d) fiscal privileges.

perpetuity

Endless years. There is a rule against perpetuities which, if infringed, will make a gift void.

cy-près

Nearest alternative gift.

The Charities Act 2006 introduced five main statutory modifications to the law of charities. These are:

1. the restatement of charitable purposes in a modern statutory form;

2. the public benefit obligation;

3. changes in the function of the Charity Commission;

4. the establishment of a Charity Tribunal;

5. the improvement of the range of legal entities that are available to charities.

The principles that were enacted in the 2006 Act have since been repealed and replaced by equivalent provisions in the Charities Act 2011. This Act was brought into force on 14 March 2012. The Charities Act 2011 is divided into 19 Parts, contains 358 sections and 11 Schedules.

Section 1(1) of the Charities Act 2011 adopts a two-tier definition of a charity. It is an institution which:

(a) is established for charitable purposes only; and

(b) falls to be subject to the control of the High Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction with respect to charities.

The definition in s 1(1)(a) of the 2011 Act is related to the test for certainty of charitable objects (see below). In addition, the institution is required to be subject to the control of the High Court. This is the jurisdictional aspect of the definition.

A number of British registered charities carry on their activities abroad. There is little judicial authority on the attitude of the courts to such overseas activities. In 1963, the Charity Commissioners issued guidelines on the way they would approach this problem. Their view is that activities of trusts within the first three heads of Lord Macnaghten’s classification (trusts for the relief of poverty, for the advancement of education and for religion) are charitable wherever such operations are conducted. In respect of the fourth head, such purposes would be charitable only if carried on for the benefit (direct or reasonably direct) of the UK community, such as medical research. The Commissioners added that it may be easier to establish this benefit in relation to the Commonwealth (although this link has become weaker since the statement was made).

The limited number of authorities in this field seem to make no distinction between activities conducted abroad as opposed to UK activities.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Keren Kayemeth Le Jisroel Ltd v IRC [1932] AC 650 A company was formed with the main object of purchasing land in Palestine, Syria and parts of Turkey for the purpose of settling Jews in such lands. It was argued that the company was established for charitable purposes, namely the advancement of religion, the relief of poverty and other purposes beneficial to the community. The court held that the company was not charitable, because of the lack of evidence of religion and poverty. In addition, the company was not charitable under the fourth head because of the uncertainty of identifying the community. |

In Re Jacobs (1970) 114 SJ 515, a trust for the planting of a clump of trees in Israel was held to be charitable because soil conservation in arid parts of Israel is of essential importance to the Israeli community. The court relied on IRC v Yorkshire Agricultural Society [1928] 1 KB 611: the promotion of agriculture is a charitable purpose.

However, if the organisation is not registered in the United Kingdom but abroad, and carries on its activities substantially abroad, the connection with the UK could be so insignificant that the English courts may reject jurisdiction. The justification for this rule is that the activities of the charity as well as the trustees will be outside the court’s control. In Gaudiya Mission v Brahmachary (1997), the Court of Appeal refused jurisdiction on the ground that the statutory and practical controls could not have been extended to such institutions.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Gaudiya Mission v Brahmachary [1997] 4 All ER 957, CA The claimant, an Indian charity (the Mission), maintained preaching centres and temples in order to advance the doctrines of the Vaishnava faith throughout India and also Cricklewood, northwest London. The Mission was not registered in England. Rival factions within the Mission set up a trust under the name ‘Gaudiya Mission Society Trust’ (the Society), which was a registered English charity. The defendants were the priest in charge of the charity’s London temple and the trustees of the English registered Society. The claimant contended that the assets held by the Society belonged to it and that the Society was passing itself off as the Mission. The question in issue was whether the Mission was an institution established for charitable purposes, and thereby subject to the control of the High Court under its supervisory jurisdiction. The judge decided that the Mission was within the control of the High Court and, consequently, that the Attorney General ought to be added as a party to the proceedings. The Attorney General appealed to the Court of Appeal. Held: The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal on the ground that the English law of charities was not applicable to institutions other than those established for charitable purposes in England and Wales. Charitable institutions within England and Wales are required to register with the Charity Commission. The legal and practical considerations of enforceability are decisive factors, which indicate that the law was never intended to extend to an institution registered abroad. Thus, the Mission was not a charity within English law and the Attorney General was not a proper party to be joined. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Under English law charity has always received special treatment. It often takes the form of a trust; but it is a public trust for the promotion of purposes beneficial to the community, not a trust for private individuals. It is therefore subject to special rules governing registration, administration, taxation and duration. Although not a state institution, a charity is subject to the constitutional protection of the Crown as parens patriae, acting through the Attorney-General, to the state supervision of the Charity Commissioners and to the judicial supervision of the High Court. This regime applies whether the charity takes the form of a trust or of an incorporated body. The English courts have never sought to subject to this regime institutions or undertakings established for public purposes under other legal systems. [The authorities] show that the courts of this country accept that they do not have the means of controlling an institution established in another country, and administered by trustees there.’ |

| Mummery LJ |

12.2 Certainty of objects

In s1(1)(a) of the Charities Act 2011, the expression, ‘charity’ has been partially defined by reference to the exclusivity of charitable purposes promoted by the institution. This is a reference to the test for certainty of the charitable objects and amounts to a statutory recognition of the common law approach that preceded the passing of the Act. At common law a charitable trust is subject to a unique test for certainty of objects, namely whether the funds of the institution are applicable for charitable purposes. In other words, if the trust funds may be used solely for charitable purposes, the test will be satisfied. Indeed, it is unnecessary for the settlor or testator to specify the charitable objects which are intended to take the trust property: provided that the trust instrument manifests a clear intention to devote the funds for ‘charitable purposes’, the test will be satisfied. Thus, a gift ‘on trust for charitable purposes’ will satisfy this test. The Charity Commission and the courts have jurisdiction to establish a scheme for the application of the funds for charitable purposes (i.e. the court will make an order indicating the specific charitable objects which will benefit).

But if the trust funds are capable of being applied in a substantial manner to promote charitable and non-charitable purposes the trust will fail to satisfy the test for certainty of charitable objects and a resulting trust may arise in favour of the settlor or his estate, if he is dead. In Morice v Bishop of Durham, the gift failed as a charity on this ground.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Morice v Bishop of Durham [1804] 9 Ves 399 A fund was given upon trust for such objects of benevolence and liberality as the Bishop of Durham should approve. The question in issue was whether the fund was charitable. |

| Held: The gift was not valid as a charity because the objects were not exclusively charitable. A resulting trust was created. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]t is now settled, upon authority, which it is too late to controvert, that, where a charitable purpose is expressed, however general, the bequest shall not fail on account of the uncertainty of the object: but the particular mode of application will be directed by the King in some cases, in others by this court. I am not aware of any case, in which the bequest has been held to be charitable, where the testator has not either used that word, to denote his general purpose or specified some particular purpose, which this court has determined to be charitable in its nature.’ |

| Grant MR |

In Moggridge v Thackwell (1807) 13 Ves 416, a bequest to ‘such charities as the trustee sees fit’ was valid as a gift for charitable purposes. The court approved a scheme for the disposition of the residuary estate.

On the other hand, where the settlor in the trust instrument identifies two sets of purposes, one set of charitable objects and another set of non-charitable objects, the court will construe the objects to determine the scope of the disposition. If the trust funds are capable of being devoted to both charitable and non-charitable purposes the gift will be invalid as a charity for uncertainty of objects.

CASE EXAMPLE

| IRC v City of Glasgow Police Athletic Association [1953] 1 All ER 747 The association promoted both a charitable purpose (efficiency of the police force) and a non-charitable purpose (promotion of sport). The court decided that the association was not charitable. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The private advantage of members is a purpose for which the association is established and it therefore cannot be said that this is an association established for a public charitable purpose only. In principle, therefore, if an association has two purposes, one charitable and the other not, and if the two purposes are such and so related that the non-charitable purpose cannot be regarded as incidental to the other, the association is not a body established for charitable purpose only.’ |

| Lord Normand |

The courts have created a distinction between on the one hand, the broad notion of a trust for benevolent purposes and on the other hand, a charitable trust for the benefit of the community. On construction, the court may decide that benevolent purposes involve objectives that are much wider than charitable purposes and accordingly the gift may fail as a charity. Thus, where the draftsman of the objects clause uses words such as ‘charitable or benevolent purposes’, the court may, on construction of the clause, decide that the word ‘or’ ought to be interpreted disjunctively, with the effect that benevolent purposes which are not charitable are capable of taking, thereby invalidating the charitable gift. In Chichester Diocesan Fund v Simpson (1944), the gift failed as a charity on construction of the objects clause.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Chichester Diocesan Fund v Simpson [1944] 2 All ER 60, HL A testator directed his executors to apply the residue of his estate ‘for such charitable or benevolent objects’ as they might select. The executors assumed that the clause created a valid charitable gift and distributed most of the funds to charitable bodies. The House of Lords decided that the clause did not create charitable gifts and therefore the gifts were void. A resulting trust was set up for the testator’s estate. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It is not disputed that the words charitable and benevolent do not ordinarily mean the same thing; they overlap in the sense that each of them, as a matter of legal interpretation, covers some common ground, but also something which is not covered by the other. It appears to me that it inevitably follows that the phrase charitable or benevolent occurring in a will must, in its ordinary context, be regarded as too vague to give the certainty necessary before such a provision can be supported or enforced. |

| The conjunction or may be sometimes used to join two words whose meaning is the same, but, as the conjunction appears in this will, it seems to me to indicate a variation rather than an identity between the coupled conceptions. | |

| I regret that we have to arrive at such a conclusion, but we have no right to set at nought an established principle such as this in the construction of wills, and I, therefore, move the House to dismiss the appeal.’ | |

| Viscount Simon LC |

Prima facie, the conjunction, ‘and’ is construed conjunctively but may exceptionally be construed disjunctively in a way similar to the word ‘or’. The construction of the expression will depend ultimately in the context in which the words were used in the trust instrument or will. In Re Best [1904] 2 Ch 354, a testator transferred property by his will for ‘such charitable and benevolent institutions in the city of Birmingham as the Lord Mayor should choose’. The court decided, on construction, that the will created a valid charitable trust.

JUDGMENT

| ‘I think the testator here intended that the institutions should be both charitable and benevolent; and I see no reason for reading the conjunction and as or.’ |

| Farwell J |

But in A-G of the Bahamas v Royal Trust Co [1986] IWLR 1001, a bequest to provide education ‘and’ welfare for Bahamian children failed as a charitable bequest. The expression ‘welfare’ was a word of wide import and, taken in the context of the expression ‘education and welfare’, was not restricted to the educational prosperity of the objects. The gift was therefore void for charitable purposes.

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]t is not easy to imagine a purpose connected with the education of a child which is not also a purpose for the child’s welfare. Thus, if welfare is to be given any separate meaning at all it must be something different from and wider than mere education, for otherwise the word becomes otiose … the phrase education and welfare in this will inevitably fall to be construed disjunctively. It follows that, for the reasons which were fully explored in the judgments in the courts below, and as is now conceded on the footing of a disjunctive construction, the trusts in paragraph (t) do not constitute valid charitable trusts.’ |

| Lord Oliver |

In Helena Partnerships Ltd v Revenue and Customs [2012] EWCA Civ 569, the Court of Appeal decided that a registered company formed to provide housing for persons other than those in need was not a charitable organisation and that corporation tax was payable on its profits.

JUDGMENT

| ‘I conclude that the provision of housing without regard to a relevant charitable need is not in itself charitable.’ |

| Lloyd LJ |

In two circumstances, an objects clause which seeks to benefit both charitable and non-charitable purposes will not fail as a charity if:

(i) The non-charitable purpose is construed as being incidental to the main charitable purpose. This involves a question of construction for the courts to evaluate the importance of each class of objects. In Re Coxen [1948] Ch 747, a bequest of 200,000 provided for the income to be paid to orthopaedic hospitals, subject to 100 per annum for dinners for trustees when they met on trust business. The issue was whether the objects were charitable. The court decided that, on construction of the relevant clause, a valid charitable gift was created. The provision for the trustees’ dinners was purely incidental to the main charitable purpose of benefiting orthopaedic hospitals.

(ii) The court is able to apportion the fund and devote the charitable portion of the fund for charitable purposes. An apportionment will be ordered where part only of the fund is payable for charitable purposes and the other part for non-charitable purposes. In the absence of circumstances requiring a different division, the court will apply the maxim ‘Equality is equity’ and order an equal division of the fund. In Salusbury v Denton (1857) 3 K & J 529, severance was permitted where an unspecified part of a fund was made for charitable purposes (the relief of poverty) and the remainder for a private purpose (the testator’s relatives).

JUDGMENT

| ‘It is one thing to direct a trustee to give a part of a fund to one set of objects, and the remainder to another, and it is a distinct thing to direct him to give either to one set of objects or to another … This is a case of the former description. Here the trustee was bound to give a part to each.’ |

| Page Wood VC |

12.3 Perpetuity

Charities are not subject to the rule against excessive duration. Indeed, many charities (schools and universities) continue indefinitely and rely heavily on donations. But charitable gifts, like private gifts, are subject to the rule against remote vesting, i.e. the subject-matter of the gift is required to vest in the charity within the perpetuity period. But even in this respect the courts have introduced a concession for charities, namely charitable unity. Once a gift has vested in a specific charity, then, subject to any express declarations to the contrary, it vests forever for charitable purposes. Accordingly, a gift which vests in one charity (A) with a gift over in favour of another charity (B) on the occurrence of an event will be valid even if the event occurs outside the perpetuity period. This concessionary rule does not apply to a gift over to a charity after a gift in favour of a non-charity. The normal rules as to vesting apply. Similarly, a gift over from a charity to a non-charity is caught by the rules as to remote vesting.

12.4 The cy-près doctrine

The advantage over private trusts is that when a gift vests in a charity then, subject to express provisions to the contrary, the gift vests for charitable purposes. Accordingly, the settlor (and his estate) is excluded from any implied reversionary interests by way of a resulting trust in the event of a failure of the charitable trust. Thus, the cy-près doctrine is an alternative to the resulting trust principle. This principle will be dealt with in more detail later in this chapter.

12.5 Fiscal advantages

A variety of tax reliefs are enjoyed both by charitable bodies and by members of the public (including companies) who donate funds for charitable purposes. A detailed analysis of such concessions is outside the scope of this book.

12.6 Registration

Section 30 of the Charities Act 2011 lays down the requirement that all charitable bodies must be registered with the Charity Commission, subject to exemptions, exceptions and small charities. Section 29 of the Charities Act 2011 deals with the register of charities, including its contents, which the Charity Commission will continue to maintain. Section 34 of the 2011 Act deals with the circumstances when the Commission may remove charities or institutions that are no longer considered to be charities.

The effect of registration is governed by s 37 of the 2011 Act. This provision declares that, except for the purposes of rectification, the organisation ‘shall be conclusively presumed to be or to have been a charity’ while it remains on the register.

12.7 Status of charitable organisations

Charitable bodies may exist in a variety of forms. The choice of charitable medium is determined by the founders of the charity.

Express trusts

An individual may promote a charitable purpose by donating funds inter vivos or by will to trustees on trust to fulfil a charitable objective. The purpose need not be specified by the donor, for the test here is whether all the purposes are charitable; for example, a trust will be charitable if the donor disposes of property on trust for ‘charitable and benevolent purposes’. It may be necessary for the trustees to draw up a scheme with the Charity Commission or with the approval of the court in order to identify the specific charitable purposes which will benefit. It was pointed out earlier that charitable trusts are exempt from the test for certainty of objects applicable to private trusts. Alternatively, the donor may identify the charitable objectives which he or she had in mind and, if these objectives are contested, the courts will decide whether the purposes are indeed charitable.

Corporations

A great deal of charitable activity is conducted through corporations. Such bodies may be incorporated by royal charter, such as the ‘old’ universities, or by special statute under which many public institutions, such as hospitals and ‘new’ universities, have been created. In addition, many charitable bodies have been created under the Companies Act 2006, usually as private companies limited by guarantee. In these circumstances, there is no need for separate trustees; since the corporations are independent persons, the property may vest directly in such bodies.

Charitable incorporated organisations

Part 11 (ss 204–250) of the Charities Act 2011 introduces provisions creating a new legal form known as a ‘charitable incorporated organisation’ (CIO). The CIO is the first legal form to be created specifically to meet the needs of charities. A CIO is a body corporate with a constitution with at least one member. The purpose of a CIO is to avoid the need for charities that wish to benefit from incorporation to register as companies and be liable to comply with regulations from Companies House and the Charity Commission. Any one or more persons may apply to the Charity Commission for a CIO to be registered as a charity. The effect of registration is that all the property of the applicant’s organisation shall become vested in the CIO. The Minister may make provisions for the winding up, insolvency, dissolution and revival of CIOs. The regulations may provide for the transfer of the property and rights of a CIO to the official custodian or another person or body or cy-près.

Unincorporated associations

A group of persons may join together in order to promote a charitable purpose. Such an association, unlike a corporation, has no separate existence. The funds are usually held by a committee in order to benefit the charitable purpose. In the absence of such a committee, the funds may be vested in the members of the association on trust for the charitable activity.

12.8 Charitable purposes

Pre-Charities Act 2011

The purpose of this section is to introduce the reader to the approach of the courts over four centuries in clarifying the law as to charitable purposes. Most of the case law is still relevant today in deciding whether a purpose is charitable or not.

Prior to the passing of the Charities Act 2011 (consolidating the provisions laid down in the Charities Act 2006), there was no statutory or judicial definition of charitable purposes. It was at one time believed that a statutory definition of charitable purposes would have created the undesirable effect of restricting the flexibility which existed in allowing the law to keep abreast with the changing needs of society.

Ever since the passing of the Charitable Uses Act 1601 (sometimes referred to as the Statute of Elizabeth I), the courts developed the practice of referring to the preamble for guidance as to charitable purposes. The preamble contained a catalogue of purposes which at that time were regarded as charitable. It was not intended to constitute a definition of charities. The purposes included in the preamble to the 1601 Act are:

SECTION

| Preamble to the Statute of Elizabeth I | |

| ‘The relief of aged, impotent and poor people; the maintenance of sick and maimed soldiers and mariners, schools of learning, free schools and scholars of universities; the repair of bridges, ports, havens, causeways, churches, sea banks and highways; the education and preferment of orphans; the relief, stock or maintenance of houses of correction; the marriages of poor maids; the supportation, aid and help of young tradesmen, handicapped men and persons decayed; the relief or redemption of prisoners or captives; and the aid or care of any poor inhabitants concerning the payments of fifteens, setting out of soldiers and other taxes.’ |

Admittedly, the above-mentioned purposes were of limited effect, but Lord Macnaghten in IRC v Pemsel [1891] AC 531 classified charitable purposes within four categories, thus:

JUDGMENT

| ‘charity in its legal sense comprises four principal divisions: ■ trusts for relief of poverty; ■ trusts for the advancement of education; ■ trusts for the advancement of religion; ■ trusts for other purposes beneficial to the community.’ |

The approach of the courts treated the examples stated in the preamble as a means of guidance in deciding on the validity of the relevant purpose. Two approaches have been adopted by the courts, namely:

■ Reasoning by analogy: the approach here is to ascertain whether a purpose has some resemblance to an example as stated in the preamble or to an earlier decided case which was considered charitable, for example the provision of a crematorium was considered charitable by analogy with the repair of churches as stated in the preamble in the following case:

JUDGMENT

| ‘What must be regarded is not the wording of the preamble, but the effect of decisions given by the Courts as to its scope, decisions which have endeavoured to keep the law as to charities moving according as new social needs arise or old ones become obsolete or satisfied.’ |

| Lord Wilberforce in Scottish Burial Reform and Cremation Society v City of Glasgow Corporation [1968] AC 138 |

■ The spirit and intendment of the preamble: this approach is much wider than the previous approach. The courts decide whether the purpose of the organisation is ‘within the spirit and intendment’ or ‘within the equity’ of the statute, unhindered by the specific purposes as stated in the preamble. In other words, the examples enumerated in the preamble are treated as the context or ‘flavour’ against which the purpose under scrutiny may be determined. In this respect it has been suggested that purposes beneficial to the community are prima facie charitable, unless they could not have been intended by the draftsman of the Statute of Elizabeth I, assuming that he was aware of the changes in society.

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]f a purpose is shown to be so beneficial or of such utility it is prima facie charitable in law, but the courts have left open a line of retreat based on the equity of the statute in case they are faced with a purpose (e.g. a political purpose) which could not have been within the contemplation of the statute even if the then legislators had been endowed with the gift of foresight into the circumstances of later centuries.’ |

| Russell LJ in Incorporated Council of Law Reporting v A-G [1972] Ch 73 |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Incorporated Council of Law Reporting v A-G [1972] Ch 73 The court decided that the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting was a charitable body, on the grounds that it advanced education and other purposes beneficial to society. The fact that the reports may be used by members of the legal profession for their ‘personal gain’ was incidental to the main charitable purposes. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In a case such as the present in which the object cannot be thought otherwise than beneficial to the community and of general public utility, I believe the proper question to ask is whether there are any grounds for holding it to be outside the equity of the statute; and I think the answer to that is here in the negative.’ |

| Russell LJ |

A second requirement for a trust to gain charitable status is that the entity exists for the public benefit, i.e. that it confers some tangible benefit to the public at large or a sufficiently wide section of the community. This feature distinguishes a charitable trust (public trust) from a private trust. In practice, the conferment of some tangible benefit was presumed to exist when the trust purpose fell within the first three categories of the Pemsel classification. With regard to the fourth category laid down in Pemsel the trustees were required to prove the existence of a benefit. The Charities Act 2011 has changed this practice.

From this brief outline of the pre-2011 law of charities three conclusions may be drawn:

■ There was no statutory definition of a charity.

■ A formidable body of case law on charitable purposes was built up over the centuries. This wealth of case law is still relevant in deciding charitable purposes today.

■ It was perceived that a presumption existed in favour of public benefit concerning the first three heads of Lord Macnaghten’s classification in Pemsel.

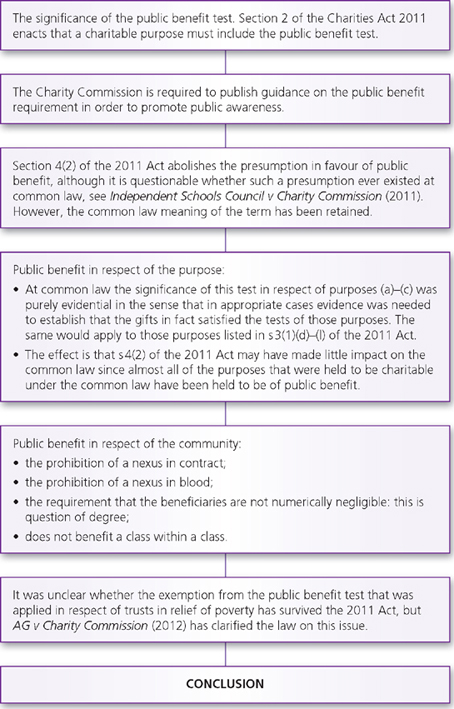

12.9 Public benefit or element

Section 2(1) of the Charities Act 2011 defines a ‘charitable purpose’ as a purpose that:

(a) falls within s 3(1) of the Act (see later); and

(b) also satisfies the definition of ‘public benefit’ as laid down in s 4 of the Act.

The effect is that a two-tier definition of charitable purposes has been adopted by the Act. We will first examine the concept of public benefit before embarking on a discussion of the 13 specific charitable purposes.

It must not be assumed that all public trusts will be treated as charitable: Chichester Diocesan Fund v Simpson [1944] AC 341 (see earlier) where a gift for ‘charitable or benevolent purposes’ failed as a charity because benevolent purposes, which were not charitable, were capable of deriving substantial benefits.

In order to qualify for charitable status the entity is required to promote a benefit to society within one or more of the purposes enacted within s 3 of the Charities Act 2011 (the benefit aspect) and the beneficiaries who are capable of enjoying the facility comprises the public or an appreciable section of the society (the public aspect), i.e. the public benefit test. In Verge v Sommerville [1924] AC 650, Lord Wrenbury commented on the public benefit requirement in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| ‘To ascertain whether a gift constitutes a valid charitable trust so as to escape being void on the ground of perpetuity, a first inquiry must be whether it is public – whether it is for the benefit of the community or of an appreciably important class of the community. The inhabitants of a parish or town, or any particular class of such inhabitants, may for instance, be the objects of such a gift, but private individuals, or a fluctuating body of private individuals, cannot.’ |

12.9.1 Public benefit

The ‘public benefit’ test is used as a means of distinguishing a public trust from a private trust. A public or charitable trust is required to exist for the benefit of the public (the community) or an appreciable section of society, with the exception of trusts for the relief of poverty. Section 4(3) of the 2011 Act consolidates the case law interpretation of the public benefit test that existed before the introduction of the Charities Act. Thus, the wealth of case law that existed over four centuries may still be relevant. Section 4(3) declares that ‘any reference to the public benefit is a reference to the public benefit as that term is understood for the purposes of the law relating to charities in England and Wales’. This test incorporates two limbs.

JUDGMENT

| ‘[The judge] would start with a predisposition that an educational gift was for the benefit of the community; but he would look at the terms of the trust critically and if it appeared to him that the trust might not have the requisite element, his predisposition would be displaced so that evidence would be needed to establish public benefit. But if there was nothing to cause the judge to doubt his predisposition, he would be satisfied that the public element was present. This would not, however, be because of a presumption as that word is ordinarily understood; rather, it would be because the terms of the trust would speak for themselves, enabling the judge to conclude, as a matter of fact, that the purpose was for the public benefit.’ |

| Warren J |

In deciding whether the ‘benefit aspect’ is satisfied, the approach of the courts is to weigh up the benefits to society as against the adverse consequences to the public and determine whether the net balance of benefits is in favour of the public. In Independent Schools Council v Charity Commission (2011), Warren J expressed the point in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The court … has to balance the benefit and disadvantage in all cases where detriment is alleged and is supported by evidence. But great weight is to be given to a purpose which would, ordinarily, be charitable; before the alleged disadvantages can be given much weight, they need to be clearly demonstated.’ |

This principle may be illustrated by the House of Lords decision in National Anti-vivisection Society v IRC [1948] AC 31. The court decided that a society whose main object was the abolition of vivisection was not charitable for its purpose was detrimental to medical science and was political in the sense that it involved a change in the law.

JUDGMENT

| ‘There is not, so far as I can see, any difficulty in weighing the relative value of what it called the material benefits of vivisection against the moral benefit which is alleged or assumed as possibly following from the success of the appellant’s project. In any case the position must be judged as a whole. It is arbitrary and unreal to attempt to dissect the problem into what is said to be direct and what is said to be merely consequential. The whole complex of resulting circumstances of whatever kind must be foreseen or imagined in order to estimate whether the change advocated would or would not be beneficial to the community.’ |

| Lord Wright |

The second requirement concerns the identification of the class of beneficiaries to be regarded as the public (the community) or an appreciable section of society. The satisfaction of the test is a question of law for the judge to decide on the evidence submitted to him. Further, the courts have decided this question in a flexible manner by reference to the description of the purposes of the entity within s 3(1) of the Charities Act 2011. In short, the public benefit test may be approached differently where the trust promotes education, relieves poverty or advances religion. In Gilmour v Coats [1949] AC 426, Lord Simonds expressed the point in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| ‘It is a trite saying that the law is life, not logic. But it is, I think, conspicuously true of the law of charity that it has been built up not logically but empirically. It would not, therefore, be surprising to find that, while in every category of legal charity some element of public benefit must be present, the court had not adopted the same measure in regard to different categories, but had accepted one standard in regard to those gifts which are alleged to be for the advancement of education and another for those which are alleged to be for the advancement of religion, and it may be yet another in regard to the relief of poverty. To argue by a method of syllogism or analogy from the category of education to that of religion ignores the historical process of the law.’ |

In IRC v Baddeley [1955] AC 572 (see below), a gift to promote recreation for a group of persons forming a class within a class did not satisfy the public benefit test. Lord Somervell expressed the flexible approach to the public benefit test, thus:

I cannot accept the principle submitted by the respondents that a section of the public sufficient to support a valid trust in one category must as a matter of law be sufficient to support a trust in any other category. I think that difficulties are apt to arise if one seeks to consider the class apart from the particular nature of the charitable purpose. They are, in my opinion, interdependent. There might well be a valid trust for the promotion of religion benefiting a very small class. It would not at all follow that a recreation ground for the exclusive use of the same class would be a valid charity.

Lord Somervell in IRC v Baddeley [1955] AC 572

In essence, this test will be satisfied if the potential beneficiaries of the trust are not numerically negligible and there is no personal bond or link between the donor and the intended beneficiaries, subject to the exception regarding trusts for the relief of poverty.

The policy that underpins the second limb of the public benefit test was laid down by Lord Simonds in IRC v Baddeley [1955] AC 572. The policy distinguishes between gifts that are limited for the benefit of a defined class of individuals on the one hand, and gifts that are available to the community as a whole, but may be enjoyed by those beneficiaries who are willing to avail themselves of the benefit. In this case, a trust in favour of Methodists in West Ham and Leyton failed the public element test because the beneficiaries were composed of a class within a class:

JUDGMENT

| ‘[There is a] distinction between a form of relief accorded to the whole community yet by its very nature advantageous only to a few and a form of relief accorded to a selected few out of a larger number equally willing and able to take advantage of it … for example, a bridge which is available for all the public may undoubtedly be a charity and it is indifferent how many people use it. But confine its use to a selected number of persons, however numerous and important; it is then clearly not a charity. It is not of general public utility; for it does not serve the public purpose which its nature qualifies it to serve.’ |

| Lord Simonds in IRC v Baddeley |

In the provision of education, the public benefit test will not be satisfied if there is a personal nexus between the donor and the beneficiaries or between the beneficiaries themselves. The personal nexus may take the form of a ‘blood’ relationship. In Re Compton [1945] 1 All ER 198, the Court of Appeal decided that the test was not satisfied where the gift was on trust for the education of the children of three named relatives:

JUDGMENT

| ‘I come to the conclusion, therefore, that on principle a gift under which the beneficiaries are defined by reference to a purely personal relationship to a named propositus cannot on principle be a valid charitable gift. And this, I think, must be the case whether the relationship be near or distant, whether it is limited to one generation or is extended to two or three or in perpetuity.’ |

| Lord Greene MR |

This test was approved and extended to a personal nexus by way of contract in Oppenheim v Tobacco Securities Trust Co Ltd [1951] AC 297, HL.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Oppenheim v Tobacco Securities Trust Co Ltd [1951] AC 297, HL Trustees were directed to apply moneys in providing for the education of employees or ex-employees of British American Tobacco or any of its subsidiary companies. The employees numbered 110,000. The court held that in view of the personal nexus between the employees themselves (being employed by the same employer), the public element test was not satisfied. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[The] words section of the community have no special sanctity, but they conveniently indicate first, that the possible (I emphasise the word possible) beneficiaries must not be numerically negligible, and secondly, that the quality which distinguishes them from other members of the community, so that they form by themselves a section of it, must be a quality which does not depend on their relationship to a particular individual.’ |

| Lord Simonds |

JUDGMENT

| ‘If the bond between those employed by a particular railway is purely personal, why should the bond between those who are employed as railwaymen be essentially different? … Are miners in the service of the National Coal Board now in one category and miners in a particular pit or of a particular district in another? Is the relationship between those in the service of the Crown to be distinguished from that obtaining between those of some other employer?’ |

More recently, in Dingle v Turner [1972] AC 601, Lord Cross of Chelsea gave his support to this view.

There is some support for the view, albeit weak, that if the donor sets up a trust for the benefit of the public or a large section of the public, but expresses a preference (not amounting to an obligation) in favour of specified individuals, the gift is capable of satisfying the public element test.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Koettgen’s Will Trust [1954] Ch 252 A trust was created for the promotion and furtherance of the commercial education of British-born subjects, subject to a direction that preference be given to the employees of a company. The court decided that, on construction, the preference was intended as permitting, without obliging, the trustees to consider distributing the property in favour of the employees. |

This decision had been criticised by the Privy Council in Caffoor v Commissioners of Income Tax, Colombo [1961] AC 584 as being in essence an ‘employee trust’ and ‘had edged very near to being inconsistent with Oppenheim’s case’.

In IRC v Educational-Grants Association Ltd [1967] 3 WLR 341, the Court of Appeal refused to follow Re Koettgen’s Will Trust (1954).

CASE EXAMPLE

| IRC v Educational-Grants Association Ltd [1967] 3 WLR 341 An association was established for the advancement of education by, inter alia, making grants to individuals. Its principal source of income consisted of annual sums paid to it by Metal Box Ltd. About 85 per cent of the association’s income during the relevant years was applied to the children of employees of Metal Box Ltd. The question in issue was whether the association was a charitable body. The Court of Appeal affirmed the decision of Pennycuick J and decided that the application of the high proportion of the income for the benefit of children connected with Metal Box Ltd was inconsistent with an application for charitable purposes. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘I find considerable difficulty in the Re Koettgen decision. I should have thought that a trust for the public with reference for a private class comprised in the public might be regarded as a trust for the application of income at the discretion of the trustees between charitable and non-charitable objects.’ |

| Pennycuick J |

In essence, the public element test will be satisfied if:

(i) the beneficiaries are not numerically negligible; and

(ii) the beneficiaries have no ‘link’ in contract or in blood between themselves or with a narrow group of individuals.

JUDGMENT

| ‘To constitute a section of the public, the possible beneficiaries must not be numerically negligible and secondly, the quality which distinguishes them from other members of the community so that they form by themselves a section of it must be a quality which does not depend on their relationship to a particular individual … A group of persons may be numerous but, if the nexus between them is their personal relationship to a single proposition or to several propositus they are neither the community nor a section of the community for charitable purposes.’ |

| Lord Simonds in Oppenheim v Tobacco Securities Trust Co (1951) |

Subject to the absence of a personal nexus between the beneficiaries and/or a limited class of individuals, the issue of whether or not the beneficiaries constitute a section of the public in order to satisfy the public element test is a question of degree. There are many decisions which appear to be inconsistent with each other. In Gilmour v Coats [1949] 1 All ER 848, HL, the court decided that a gift to a community of 20 cloistered nuns who devoted themselves to prayer and contemplation did not satisfy the public element test:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The community [order of nuns] does not engage in – indeed, it is by its rules debarred from – any exterior work, such as teaching, nursing, or tending the poor, which distinguishes the active branches of the same order.’ |

| Lord Simonds |

On the other hand, in Neville Estates Ltd v Madden [1962] 1 Ch 832, the members of the Catford Synagogue were treated as an appreciable section of the public and satisfied the public element test because they integrated with the rest of society.

JUDGMENT

| ‘The two cases [Gilmour v Coats and Neville Estates v Madden], however, differ from one another in that the members of the Catford Synagogue spend their lives in the world, whereas the members of a Carmelite Priory live secluded from the world.’ |

| Cross J |

In Re Lewis [1954] 3 All ER 257, a gift to ten blind boys and ten blind girls in Tottenham was charitable. But in Williams’ Trustees v IRC [1947] AC 447, HL, a gift in order to create an institute in London for the promotion of Welsh culture failed as a charity:

JUDGMENT

| ‘I doubt whether the public benefit test could be satisfied if the beneficiaries are a class of persons not only confined to a particular area but selected from within the area by reference to a particular creed … the persons to be benefited must be the whole community, or all the inhabitants of a particular area. Not a class within a class.’ |

| Lord Simonds |

The same principle was applied in IRC v Baddeley (1955) (see above).

In 2008, the Charity Commission published guidelines on the public benefit requirement and declared that the test will not be satisfied, as stated in paras 2(b) and (c) of the guide, if the provision of the benefit is determined by the ability to pay fees charged and excludes people in poverty. In Independent Schools Council v Charity Commission [2011] UKUT 421, the Upper Tribunal, in judicial review proceedings, decided that the Charity Commission guidelines were defective and ought to be quashed in respect of paras 2(b) and (c) as stated above. The issue in the proceedings concerned the accuracy of the Charity Commission’s published guidelines on the public benefit requirement and its application to fee-paying independent schools. Charitable independent schools would fail to act for the public benefit if they failed to provide some benefit for its potential beneficiaries, other than its fee-paying students. The Upper Tribunal decided that it was a matter for the trustees to decide how their obligations might be fulfilled. Benefits for potential beneficiaries who may not have the capacity to pay the full fees for their education may be provided in a variety of ways including, for example, the remission of all or partial fees to ‘poor’ students and the sharing of educational facilities with the maintained sector.

As a result of the judgment in the Independent Schools Council case, the Charity Commission modified its guidelines on public benefit. The salient points in the guidelines include the following:

■ There are two aspects of public benefit – the ‘benefit’ and ‘public’ aspects.

● The ‘benefit aspect’ involves an inquiry as to whether the trust purposes comply with one or more of the 13 purposes laid down in s 2 of the Charities Act 2011, and any detriment or harm that results from the purpose does not outweigh the benefit. The benefit is required to be identifiable and capable of being proved, where necessary. In some cases the purpose may be so clearly beneficial that there may be little need for trustees to provide evidence of this.

● The ‘public aspect’ concerns those who may benefit from the funds of the trust and is required to be the public in general, or a sufficient section of the public. There is no set minimum number of persons who may comprise a sufficient section of the public. This issue is decided on a case-by-case basis and the approach is not the same for every purpose. With the exception of trusts for the relief or prevention of poverty, the test will not be satisfied if the beneficiaries are identified by reference to their family relationship, employment by an employer or membership of an unincorporated association.

12.9.2 Public benefit and poverty exception

Before the introduction of the Charities Act 2011 (or the Charities Act 2006, which was consolidated in the 2011 Act) the courts adhered to the view that trusts for the relief of poverty were exempt from the public benefit test. Trusts for the relief of poverty are charitable even though the beneficiaries are linked inter se or with an individual or small group of individuals. In short, it is arguable that trusts for the relief of poverty are not subject to the strict public benefit test. The practice of the courts has always been to exclude such trusts from the public benefit test.

The justification for this exception or exemption is that the creation of such trusts is prompted by motives of altruism with inherently public benefit characteristics, see Lord Greene’s judgment in Re Compton [1945] Ch 123:

JUDGMENT

| ‘There may perhaps be some special quality in gifts for the relief of poverty which places them in a class by themselves. It may, for instance, be that the relief of poverty is to be regarded as in itself so beneficial to the community that the fact that the gift is confined to a specified family can be disregarded.’ |

Accordingly, in Gibson v South American Stores Ltd [1950] Ch 177 and Dingle v Turner [1972] AC 601, the courts decided that gifts in order to relieve the poverty of employees of a company were charitable.

JUDGMENT

| ‘[C]ounsel for the appellant hardly ventured to suggest that we overrule the poor relations cases. His submission was that which was accepted by the Court of Appeal for Ontario in In Re Cox [1951] OR 205 – namely that while the poor relations cases might have to be left as longstanding anomalies there was no good reason for sparing the poor employees cases which only date from In Re Gosling [1900] 48 WR 300, and which have been under suspicion ever since the decision in In Re Compton. But the poor members and the poor employees decisions were a natural development of the poor relations decisions and to draw a distinction between different sorts of poverty trusts would be quite illogical and could certainly not be said to be introducing greater harmony into the law of charity. Moreover, though not as old as the poor relations trusts poor employees trusts have been recognised as charities for many years; there are now a large number of such trusts in existence; and assuming, as one must, that they are properly administered in the sense that benefits under them are only given to people who can fairly be said to be, according to current standards, poor persons, to treat such trusts as charities is not open to any practical objection. So it seems to me it must be accepted that wherever else it may hold sway the Compton rule has no application in the field of trusts for the relief of poverty.’ |

| Lord Cross |

At the same time, the courts have drawn a subtle distinction between private trusts for the relief of poverty and public trusts for the same purpose. The distinction has been expressed as a private trust for identifiable individuals with the motive of relieving poverty, and a charitable trust in order to relieve poverty amongst a class of persons; for example a gift for the settlor’s poor relations, A, B and C, may not be charitable but may exist as a private trust, whereas a gift for the benefit of the settlor’s poor relations without identifying them may be charitable. It appears that the distinction between the two types of trust lies in the degree of precision in which the objects have been identified. The more precise the language used by the settlor in identifying the poor relations, the stronger the risk of failure as a charitable trust. This is a question of degree.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Scarisbrick [1951] Ch 622, CA A bequest was made on trust ‘for such relations of my said son and daughters as in the opinion of the survivor shall be in needy circumstances’. The court held that the gift was charitable. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[T]he true question in each case [is] whether the gift was for the relief of poverty amongst a class of persons, or rather … a particular description of poor, or was merely a gift to individuals, albeit with relief of poverty amongst those individuals as the motive of the gift … It should be added that the class of beneficiaries falls to be ascertained at the death of the survivor of the three children, not at the testatrix’s death. Thus, the class of beneficiaries is so extensive as to be incapable of being exhaustively ascertained and includes persons who the testatrix may never have seen or heard of.’ |

| Jenkins LJ |

The court came to a similar conclusion in Re Segelman [1996] 2 WLR 173. Chadwick J was influenced by the fact that the class of ‘poor and needy’ relatives was not closed on the date of the testator’s death. The list of beneficiaries included six named members of the testator’s family and the issue (unnamed) of five of them who were ‘poor and needy’, provided that they were born within 21 years following the death of the testator. There were 26 persons within the class. The court decided that the gift was charitable for the relief of poverty.

JUDGMENT

| ‘Prima facie, a gift for the benefit of poor and needy persons is a gift for the relief of poverty … [and] is no less charitable because those whose poverty is to be relieved are confined to a particular class limited by ties of blood or employment: see In Re Scarisbrick [1951] Ch 622; and Dingle v Turner [1972] AC 601. The gift with which I am concerned has, in common with the gift which the Court of Appeal had to consider in Re Scarisbrick, the feature that the class of those eligible to benefit was not closed upon the testator’s death. It remained open for a further period of 21 years. During that period issue of the named individuals born after the death of the testator will become members of the class. It is, in my view, impossible to attribute to the testator an intention to make a gift to those after-born issue as such. His intention must be taken to have been the relief of poverty amongst the class of which they would become members.’ |

| Chadwick J |

The position today is that there is an element of ambiguity as to whether trusts for the relief of poverty are subject to a different test of public benefit since the introduction of the Charities Act 2011 (or its predecessor, the Charities Act 2006). On the one hand, no such concession has been enacted in s 4 of the 2011 Act and any presumptions regarding public benefit have been abolished. On the other hand, s 4(3) consolidates the common law meaning of public benefit and declares that ‘any reference to the public benefit is a reference to the public benefit as that term is understood’. The Charity Commission and the Attorney General’s office are concerned that the law on public benefit may have been modified by statute, but recognise that it is only a question of time before the courts consider the issue. The possible outcomes are:

(a) The law has been changed and trusts for the relief of poverty are subject to the rigorous public benefit test.

(b) The law has not been modified and a special approach to the public benefit test in the context of trusts for the relief of poverty remains.

(c) A third approach is that the law in this context has been changed, not retrospectively, but only from the date that the Charities Act 2006 came into force, namely 1 April 2008. The provisions of the Charities Act 2006 were consolidated in the Charities Act 2011. The effect may be that the funds of charitable trusts for the relief of poverty that existed before 1 April 2008 which contain a ‘personal nexus’ may be applied cy-près.

However, in Attorney General v Charity Commission [2012] WTLR 977, the Upper Tribunal allayed fears that the public benefit test applicable to trusts for the relief of poverty has been modified by the Charities Act. The Upper Tribunal clarified this area of the law on the test of public benefit. The Upper Tribunal ruled that the pre-2008 approach of the courts is still relevant and applicable today to determine whether the public benefit test for the relief of poverty is satisfied.

The Attorney General v Charity Commission case involved a non-adversarial reference by the Attorney General. The Upper Tribunal published its opinion on the public benefit requirement that is applicable to charitable trusts for the relief of poverty. The Tribunal decided:

(i) Where a trust for the relief of poverty is limited, owing to a personal nexus, by reference to a class of individuals, their employment by a commercial company, or their membership of an unincorporated association, the trust was nevertheless capable of satisfying the public benefit test.

(ii) Such trusts are not automatically treated as charitable but the approach is based on whether the evidence satisfies the dual nature test for public benefit.

(iii) The abolition of the presumption of public benefit by statute will have no impact on whether a trust for the relief of poverty is charitable or not.

(iv) In deciding whether a trust satisfied the public benefit test in the pre-Charities Act era, the courts had proceeded not by way of presumption, but on the evidence that existed on the facts of each case.

(v) There was no real distinction between the expressions ‘prevention’ and ‘relief of poverty, as used in the Charities Act 2011.

In 2013 the Charity Commission published its guidelines on the public benefit requirement and affirmed that trusts for the relief of poverty were subject to a broader set of rules. The public benefit requirement may be met by satisfying the ‘benefit’ aspect only. Accordingly, trusts for the relief of poverty may satisfy the public benefit test where the beneficiaries are defined by reference to their family relationship, employment by an employer or membership of an unincorporated association. But the test will not be satisfied if the beneficiaries comprise a group of named individuals.

12.9.3 Classification of charitable purposes

Prior to the introduction of the Charities Act 2006 (consolidated in the Charities Act 2011), a useful classification of the charitable purposes, laid down in the preamble to the Charitable Uses Act 1601 (see earlier), was adopted by Lord Macnaghten in IRC v Pemsel (1891), as follows:

(a) the relief of poverty;

(b) the advancement of education;

(c) the advancement of religion; and

(d) other purposes beneficial to the community.

It must be emphasised that Lord Macnaghten’s statement did not constitute a definition of charitable purposes but merely a classification of the purposes within the preamble. In short, prior to the Charities Act 2006, there was no comprehensive definition of charitable purposes. The purposes stated in the preamble (albeit obsolete) were the closest to a definition of charitable purposes. It became the practice of the courts to refer back to the preamble or precedents decided in accordance with the purposes within the preamble or indeed the ‘spirit’ (or flavour) of the preamble.

There is no doubt that the classification of charitable purposes and approaches of the courts have provided a degree of flexibility that has allowed the meaning of charity to adapt to the changing needs and expectations of society. However, the four heads of charity provide little effective guidance to the public about what is a charitable purpose. The classification of charitable purposes by Lord Macnaghten is a vague indication of some charitable activities. Charitable purposes extend beyond education, religion and relief of the poor. Indeed, but for the creative approach of the courts, as evidenced by the multitude of judicial decisions, the law of charities would have been in a state of disarray. This state of affairs prompted Lord Sterndale MR in Re Tetley [1923] 1 Ch 258 to express his dissatisfaction at being unable to find any guidance as to what constitutes a charitable purpose:

JUDGMENT

| ‘I am unable to find any principle which will guide one easily and safely through the tangle of cases as to what is and what is not a charitable gift. If it is possible I hope sincerely that at some time or other a principle will be laid down.’ |

Section 3 of the Charities Act 2011 addresses some of these limitations by adopting a statutory definition of ‘charitable purposes’. This is achieved by reference to a two-step approach – the listing or identification of a variety of charitable purposes, and the public benefit test. This is the first-ever statutory definition of a charity. Section 3(1) contains a list of some 13 charitable purposes – 12 specific descriptions of charitable purposes and a general provision designed to maintain flexibility in the law of charities. The charitable purposes enacted are intended to be a comprehensive list of charitable activities. Most of these purposes, in any event, were charitable before the Act was introduced. These purposes are:

(a) the prevention or relief of poverty;

(b) the advancement of education;

(c) the advancement of religion;

(d) the advancement of health (including the prevention or relief of sickness, disease or human suffering);

(e) the advancement of citizenship or community development;

(f) the advancement of the arts, heritage or science;

(g) the advancement of amateur sport (games which promote health by involving physical or mental skill or exertion);

(h) the advancement of human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation;

(i) the advancement of environmental protection or improvement;

(j) the relief of those in need, by reason of youth, age, ill-health, disability, financial hardship or other disadvantage (including the provision of accommodation and care to the beneficiaries mentioned within this clause);

(k) the advancement of animal welfare;

(l) the promotion of the efficiency of the armed forces of the Crown, or of the efficiency of the police, fire and rescue services or ambulance services;

(m) any other purposes (the residual category).

With the exception of amateur sport, arguably, all of these purposes were charitable under the law that existed before the 2011 Act, as illustrated by the wealth of case law.

Section 3(3) endorses the common law approach to charitable objects by reference to the purposes declared in paragraphs (a) to (1) above. This is done by determining whether a purpose has some resemblance to an example as stated in the preamble, or to an earlier decided case that was considered charitable. In these cases the same meaning will be attributable to the term. Section 3(3) of the 2011 Act states that ‘where any of the terms used in any of the paragraphs (a) to (1)… has a particular meaning under the law relating to charities in England and Wales, the term is to be taken as having the same meaning where it appears in that provision’.

Section 3(1)(m)(i)–(iii) consolidates the common law approach to the residual category of charitable purposes.

SECTION

| ‘Other purposes– | |

(i) that are not within paragraphs (a) to (I) but are recognised as charitable purposes by virtue of section 5 (recreational and similar trusts, etc.) or under the old law; (ii) that may reasonably be regarded as analogous to, or within the spirit of, any purposes falling within any of the paragraphs (a) to (I)…; (iii) that may reasonably be regarded as analogous to, or within the spirit of, any purposes which have been recognised, under the law relating to charities in England and Wales, as falling within sub-paragraph (ii) or this paragraph.’ |

This subsection affirms the pre-2008 (the date that the Charities Act 2006 came into force) broad approach to purposes within the fourth heading of the Pemsel classification as summarised by Lord Wilberforce in Scottish Burial Reform and Cremation Society v City of Glasgow Corporation [1968] AC 138, including the ‘spirit’ of charitable purposes, thus:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The purposes in question, to be charitable, must be shown to be for the benefit of the public, or the community, in a sense or manner within the intendment of the preamble to the [Charitable Uses Act 1601]. The latter requirement does not mean quite what it says; for it is now accepted that what must be regarded is not the wording of the preamble itself, but the effect of decisions given by the court as to its scope, decisions which have endeavoured to keep the law as to charities moving according as new social needs arise or old ones become obsolete or satisfied.’ |

12.9.4 Consideration of the charitable purposes

Category 1: the prevention or relief of poverty

Section 3(1)(a) of the Charities Act 2011 enacts that the ‘prevention or relief of poverty’ is capable of being a charitable purpose. As stated earlier, this description consolidates the common law approach. Very little turns on the distinction between ‘prevention’ and ‘relief. Lord MacNaghten in Pemsel, in classifying charitable purposes, referred to trusts for the ‘relief of poverty but case law and the Charity Commission drew no distinction between ‘prevention’ and ‘relief. Accordingly, trusts for the provision of the basic essentials of life, agriculture, irrigation and shelter in order to prevent an impending natural disaster are as much charitable as dealing with the consequences of such disasters.

‘Poverty’ includes destitution but is not interpreted so narrowly as to mean destitution. It connotes that the beneficiaries are in straitened circumstances and unable to maintain a modest standard of living (determined objectively).

The Charity Commission in its report in December 2008 explained the concept of poverty:

QUOTATION

| ‘The expression, “people in poverty” does not just include people who are destitute, but also those who cannot satisfy a basic need without assistance. The courts have avoided setting an absolute criteria to be met in order for poverty to be said to exist, although they have been prepared to state in specific cases whether or not a particular level of income or assets meant that a person was “poor”. In essence, “people in poverty” generally refers to people who lack something in the nature of necessity or quasi-necessity, which the majority of the population would regard as necessary for a modest, but adequate standard of living.’ |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Coulthurst [1951] Ch 661, CA A bequest of £20,000 to trustees was subject to the direction that the income be paid to the widows and orphans of deceased officers and ex-officers of Coutts & Co, as the trustees may decide the most deserving of such assistance, having regard to their financial circumstances. The court decided that, on construction of the terms of the gift, the gift was charitable for the relief of poverty. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Poverty does not mean destitution; it is a word of wide and somewhat indefinite import; it may not unfairly be paraphrased for present purposes as meaning persons who have to go short in the ordinary acceptation of that term, due regard being had to their status in life and so forth.’ |

| Evershed MR |

In addition, the gift is required to relieve the misery of poverty by providing the basic necessities of human existence – food, shelter and clothing. The expression ‘relief signifies that the beneficiaries have a need attributable to their condition which requires alleviating and which the beneficiaries may find difficulty in alleviating from their own resources.

In Biscoe v Jackson (1887) 25 Ch D 460, a gift to establish a soup kitchen in Shoreditch was construed as a valid charitable trust for the relief of poverty. Likewise, in Shaw v Halifax Corporation [1915] 2 KB 170 it was decided that a home for ladies in reduced circumstances was charitable. Similarly, in Re Clarke [1923] 2 Ch 407 a gift to provide a nursing home for persons of moderate means was charitable. But a gift for the ‘working classes’ does not necessarily connote poverty: see Re Saunders’ Will Trust [1954] Ch 265, although a gift for the construction of a ‘working men’s hostel’ was construed as charitable under this head: see Re Niyazi’s Will Trust [1978] 1 WLR 910.

JUDGMENT

| ‘The word hostel has to my mind a strong flavour of a building which provides somewhat modest accommodation for those who have some temporary need for it and are willing to accept accommodation of that standard in order to meet the need. When hostel is prefixed by the expression working men’s, then the further restriction is introduced of this hostel being intended for those with a relatively low income who work for their living, especially as manual workers.’ |

| Megarry VC in Re Niyazi |

Under this head of poverty, it is essential that all the objects fall within the designation ‘poor’. If someone who is not poor is able to benefit significantly from the funds, the gift will fail as not being one for the relief of poverty. In Re Gwyon [1930] 1 Ch 225, a trust to provide free trousers for boys resident in Farnham was not charitable because there was no restriction to the effect that the boys were required to be poor.

Relief of poverty maybe provided directly for the intended beneficiaries, and includes: apprenticing poor children, see AG v Minshull (1798) 4 Ves 11; the provision of allotments or buying land to be let to the poor at a low rent, see Crafton v Firth (1851) 4 De G & Sm 237; the provision of cheap flats to be let to aged persons of small means at rents that they can afford to pay, see Re Cottam [1955] 1 WLR 1299; gifts for the establishment or support of institutions for the benefit of particular classes of poor persons such as railway servants, see Hull v Derby Sanitary Authority (1885) 16 QBD 163; and policemen, see Re Douglas (1887) 35 Ch D 472. Relief may be provided indirectly, such as providing accommodation for relatives coming from a distance to visit patients critically ill in hospital, see Re Dean’s Will Trust [1950] 1 All ER 882; a home of rest for nurses at a particular hospital, see Re White’s Will Trust [1951] 1 All ER 528.

As stated earlier, the approach of the courts to the public benefit test has been fairly relaxed in this context.

Category 2: the advancement of education

Section 3(1)(b) of the Charities Act 2011 identifies the advancement of education as a charitable purpose. This classification originates from the preamble to the 1601 Act, which refers to ‘the maintenance of schools of learning, free schools and scholars in universities’.

The Charity Commission in its Guide for Consultation, published in March 2008, identified many forms of education.

QUOTATION

| ‘Education today includes: | |

■ formal education; ■ community education; ■ physical education and development of young people; ■ training (including vocational training) and life-long learning; ■ research and adding to collective knowledge and understanding of specific areas of study and expertise; ■ the development of individual capabilities, competencies, skills and understanding.’ | |

| Charity Commission 2008 |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Hopkins’ Will Trust [1964] 3 All ER 46 Money was bequeathed to the Francis Bacon Society, to be used to search for the manuscripts of plays commonly ascribed to Shakespeare but believed by the Society to have been written by Bacon. The court decided that the gift was for the advancement of education. The discovery of such manuscripts would be of the highest value to history and literature. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The word education must be used in a wide sense, certainly extending beyond teaching, and the requirement is that, in order to be charitable, research must either be of educational value to the researcher or must be so directed as to lead to something which will pass into the store of educational material, or so as to improve the sum of communicable knowledge in an area which education may cover – education in this last context extending to the formation of literary taste and appreciation.’ |

| Wilberforce J |

More recently, Slade J in McGovern v A-G [1981] 3 All ER 493 summarised the principles governing research:

JUDGMENT

| ‘(i) A trust will ordinarily qualify as a charitable trust if, but only if, (a) the subject matter of the proposed research is a useful object of study; and (b) it is contemplated that the knowledge acquired as a result of the research will be disseminated to others; and (c) the trust is for the benefit of the public, or a sufficiently important section of the public. (ii) In the absence of a contrary context, however, the court will be readily inclined to construe a trust for research as importing subsequent dissemination of the results thereof. (iii) Furthermore, if a trust for research is to constitute a valid trust for the advancement of education, it is not necessary either (a) that the teacher/pupil relationship should be in contemplation, or (b) that the persons to benefit from the knowledge to be acquired should be persons who are already in the course of receiving “education” in the conventional sense.’ |

On the other hand, the mere acquisition of knowledge without dissemination or advancement will not be charitable. The emphasis here is on the publication or sharing of the information or knowledge.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Shaw; Public Trustee v Day [1957] 1 All ER 745 The testator, George Bernard Shaw, bequeathed money to be used to develop a 40-letter alphabet and translate his play Androcles and the Lion into this alphabet. The court held that the gift was not charitable, as it was aimed merely at the increase of knowledge. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The research and propaganda enjoined by the testator seem to me merely to tend to the increase of public knowledge in a certain respect, namely, the saving of time and money by the use of the proposed alphabet. There is no element of teaching or education combined with this, nor does the propaganda element in the trusts tend to more than to persuade the public that the adoption of the new script would be a good thing, and that, in my view, is not education.’ |

| Harman J |

Gifts which have been upheld as charitable under this head have included: trusts for choral singing in London (Royal Choral Society v IRC [1943] 2 All ER 101); the diffusion of knowledge of Egyptology and the training of students in Egyptology (Re British School of Egyptian Archaeology [1954] 1 All ER 887); the encouragement of chess playing by boys or young men resident in the city of Portsmouth (Re Dupree’s Trusts [1944] 2 All ER 443); the furtherance of the Boy Scout movement by helping to purchase sites for camping (Re Webber [1954] 3 All ER 712); the promotion of the education of the Irish by teaching self-control, elocution, oratory, deportment and the arts of personal contact and social intercourse (Re Shaw’s Will Trust [1952] 1 All ER 712); the publication of law reports which record the development of judge-made law (Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales v A-G [1971] 3 All ER 1029); the promotion of the works of a famous composer (Re Delhis’ Will Trust [1957] 1 All ER 854) or celebrated writer (Re Shakespeare Memorial Trust [1923] 2 Ch 389); the students’ union of a university (Baldry v Feintuck [1972] 2 All ER 81); the furtherance of the Wilton Park project, i.e. a conference centre for discussion of matters of international importance (Re Koeppler’s Will Trust [1986] Ch 423); the provision of facilities at schools and universities to play association football or other games (IRC v McMullen [1981] AC 1); and professional bodies which exist for the promotion of the arts or sciences (Royal College of Surgeons of England v National Provincial Bank Ltd [1952] 1 All ER 984). Many of these purposes will now overlap with other specified purposes laid down in the Charities Act 2006.

Before deciding whether the gifts are charitable or not, the courts are required to take into account the usefulness of the gifts to the public. This may be effected by judicial notice of the value of the gift to society. In the event of doubt, the courts may take into account the opinions of experts. The opinions of the donors are inconclusive. In Re Pinion [1965] Ch 85, a gift to the National Trust of a studio and contents to be maintained as a collection failed as a charity. The collection as a whole lacked any artistic merit. The judge could conceive of no useful purpose in foisting on the public this ‘mass of junk’.