Chapter 38 Self-employment income: How to file Schedule C ey.com/EYTaxGuide

More and more people work for themselves. Whether your business is your sole source of income, it supplements other income, or is new or existing, you will face a number of perplexing tax questions that ordinary wage earners do not face. What income do you report? What expenses can you deduct? What forms do you need to file?

Unlike a partnership or a regular corporation, a sole proprietorship is not a separate entity for tax purposes. (A limited liability company [LLC] which has only one member, is treated as a sole proprietorship for tax purposes.) In a sole proprietorship, you and your business are one and the same. You report net profit or loss for the year from a sole proprietorship on Form 1040, Schedule C (or Schedule C-EZ), and it becomes part of your adjusted gross income. In addition to owing income tax on such income, you, as the sole proprietor, usually will be liable for self-employment tax, and will also be required to make payments of estimated taxes. A net loss from the business generally can be deducted when you compute your adjusted gross income (see Hobby loss rules

This chapter concentrates on how a sole proprietorship recognizes business profit and losses on Form 1040, Schedule C, and Schedule SE. Examples of completed forms are included at the end of this chapter.

Self-employment. Millions of Americans are self-employed. The good news is that self-employment can provide a number of tax advantages not available to employees. For example, expenses you incur as an entrepreneur are deductible in calculating your adjusted gross income (AGI), but an employee can only deduct such expenses as miscellaneous itemized deductions, if they itemize, and if expenses are greater than 2% of their AGI. (See chapter 29 Miscellaneous deductions for more information.) Self-employed individuals can also establish their own retirement plans and deduct contributions to those plans. On the other hand, the self-employed have to pay a larger amount of social security and Medicare taxes than employees.

You may want to see:

15 Circular E, Employer’s Tax Guide15-A Employer’s Supplemental Tax Guide225 Farmer’s Tax Guide334 Tax Guide for Small Business463 Travel, Entertainment, Gift and Car Expenses535 Business Expenses541 Partnerships587 Business Use of Your Home (Including Use by Day-Care Providers) If you are a sole proprietor, an independent contractor, a statutory employee, a statutory nonemployee, or a single member LLC, you may be required to report business income and expenses on Schedule C.

Sole proprietor. If you operate a business as a sole proprietor, you must file Schedule C to report your income and expenses from your business. If you operate more than one business, or if you and your spouse had separate businesses, you must prepare a separate Schedule C for each business.

Husband-wife businesses. If spouses carry on a business together and share in the profits and losses, they may be partners whether or not they have a formal partnership agreement. If so, they should report income or loss from the business on Form 1065, U.S. Return of Partnership Income. They should not report the income on Schedule C (Form 1040) in the name of one spouse as a sole proprietor. However, a husband and wife can elect not to treat the joint venture as a partnership if they meet each of the following requirements:

The only members of the joint venture are the husband and wife. The husband and wife file a joint return. Both spouses materially participate in the business. Both spouses elect this treatment. Note: The election not to treat the joint venture as a partnership is not revocable without IRS consent.

Independent contractor. A person whose work hours and procedures are not controlled by another and who is therefore deemed to be self-employed for tax purposes must also file a Schedule C.

Statutory employee. If you are a statutory employee, you should file Schedule C. If you file Schedule C, you can deduct certain business expenses when computing your adjusted gross income. A statutory employee’s business expenses will not be subject to the reduction by 2% of his or her adjusted gross income that applies to “regular” employee business expenses reported as a part of Schedule A, Itemized Deductions. A statutory employee includes the following occupations:

Certain agent and commission drivers Full-time life insurance sales representatives Certain home workers performing work, according to specifications furnished by the person for whom the services are performed Certain traveling or city salespeople who work full-time (except for sideline sales activities) for one firm or person, soliciting orders from customers If you meet the definition of a statutory employee, your employer will indicate this classification by checking box 13, “Statutory employee,” on your Form W-2. This indicates to the IRS that you have the right to report your income and expenses on Schedule C.

As a statutory employee, you are considered an employee for social security and Medicare purposes. However, if you and your employer agree, federal income tax withholding is optional, rather than mandatory.

A statutory employee reports his or her wages from box 1 of Form W-2 on line 1 of Schedule C. He or she then deducts allowable expenses on Part II of Schedule C to arrive at reportable income.

Statutory nonemployee. If you are a statutory nonemployee, you must file Schedule C to report your income and expenses.

There are two categories of statutory nonemployees. The two categories are a direct seller of consumer products and a licensed real estate agent. They are treated as self-employed for federal income tax and employment tax purposes if:

Substantially all payments for their services as direct sellers or real estate agents are directly related to sales or other output, rather than to the number of hours worked; and Their services are performed under a written contract providing that they will not be treated as employees for federal tax purposes. Direct sellers. Direct sellers are persons:

Engaged in selling (or soliciting the sale of) consumer products in the home or at a place of business other than a permanent retail establishment; or Engaged in selling (or soliciting the sale of) consumer products to any buyer on a buy-sell basis, a deposit-commission basis, or any similar basis prescribed by regulations for resale in the home or at a place of business other than a permanent retail establishment. Direct selling also includes activities of individuals who attempt to increase direct sales activities of their direct sellers and who earn income based on the productivity of their direct sellers. Such activities include providing motivation and encouragement; imparting skills, knowledge, or experience; and recruiting.

Licensed real estate agents. This category includes real estate agents as well as individuals engaged in appraisal activities for real estate sales, if they earn income based on sales or other output.

Unlike a statutory employee, a statutory nonemployee is not subject to social security and Medicare withholding. Therefore, he or she is required to pay self-employment tax on net earnings. Additionally, federal income tax withholding is not required; therefore, estimated taxes must be paid.

Single Member LLC (limited liability company). If you operate your business through a single member LLC (this is generally done for liability purposes), you should report your income and expenses with respect to the LLC activity on Schedule C.

Schedule C is used to report income and related expenses applicable to the above activities. Income includes cash, property, and services received from all sources, unless specifically excluded under the tax code. Expenses include all ordinary and necessary expenses incurred in connection with the activity.

For sole proprietorships in the business of selling goods or inventory, the primary expense will be the cost of goods sold. The cost of goods sold represents the cost of materials, labor, and overhead included in the inventory sold during the year. Other expenses you may deduct on Schedule C include salaries and wages, interest on loans used in the activity, rent, depreciation, bad debts, travel, 50% of entertainment expenses, insurance, real estate taxes, state and local taxes, and an allocable portion of your tax return preparation fee.

Schedule C-EZ. You may use Schedule C-EZ instead of Schedule C if you operated a business or practiced a profession as a sole proprietorship and you have met all of the requirements listed below:

Had business expenses of $5,000 or less Used the cash method of accounting Did not have an inventory at any time during the year Did not have a net loss from your business Had only one business as a sole proprietor, qualified joint venture, or statutory employee and you:

Had no employees during the year Are not required to file Form 4562, Depreciation and Amortization, for this business Do not deduct expenses for business use of your home Do not have prior year, disallowed passive activity losses from this business The net income or net loss calculated on Schedule C is reported on page 1 of Form 1040. The net income or net loss (subject to certain limitations) generated on your Schedule C will cause either an increase or a decrease to adjusted gross income (AGI).

It is important to note that if you are filing Schedule C or Schedule C-EZ, you must use Form 1040, not Form 1040A or Form 1040-EZ.

Losses. If Schedule C expenses exceed Schedule C income, a loss will result. There is a possibility the amount of Schedule C loss that can be deducted on your current year’s income tax return may be limited. The amount of the loss that can be deducted on your return depends on whether you materially participate in the operation of the business (defined below), and/or whether you have enough investment at risk to cover the loss.

Reporting losses several years in a row on Schedule C may increase the risk that you will be subject to an IRS audit. The IRS monitors Schedule C filers to see if the “hobby loss” rules apply to their returns. Schedule C filers should make sure they understand the hobby loss rules (see below) when entering into ventures that will produce losses in the early years of operation. The ability to prove material participation will most likely result in no change to the amount of loss you claim on Schedule C, should you be audited.

Defining material participation. You are treated as a material participant only if you are involved in the operations of the activity on a regular, continuous, and substantial basis. If you are not a material participant in an activity, but your spouse is, you are treated as being a material participant, and the activity is not considered passive. A passive activity involves the conduct of any trade or business in which you do not materially participate.

For more information about passive activities and the at-risk limitation, see chapter 12 Other income , and IRS Publication 925, Passive Activity and At-Risk Rules .

What is a hobby loss? The IRS presumes that an activity which produces net income in 3 or more taxable years within a period of 5 consecutive years is engaged in for profit. Therefore, if an activity produces a loss for 3 or more years in a consecutive 5-year period, the IRS may infer that the activity is not engaged in for profit and disallow the loss.

Carrybacks and carryforwards. If you have incurred a Schedule C loss, it is possible that the loss may be large enough to offset all taxable income reported on your Form 1040. If this is the case, you may have generated a net operating loss (NOL).

Net operating loss. If you have incurred a net operating loss (NOL) in 2014, you can carry back or carry forward the loss and utilize it to offset income in other years. Generally, an NOL can be carried back 2 years and forward 20 years.

A business owner with an NOL realized in a year beginning or ending in 2008 or 2009 may elect to carry back the NOL to as many as 5 previous tax years rather than 2 years. This applies to owners of businesses that operate as partnerships and S corporations, as well as sole proprietorships. NOLs incurred in 2001 and 2002 could also be carried back 5 years instead of 2 years. Earlier NOLs from pre-1998 tax years expire after 15 carryforward years. Victims of theft or casualty and sole proprietorships with less than $5 million in gross receipts that incurred losses attributable to presidentially declared disaster areas are subject to a 3-year carryback period. You may elect not to carry back your NOL. If you make this election, you may use your NOL only during the 20-year carryforward period. To make this election, attach a statement to your tax return for the NOL year. This statement must show that you are electing to forgo the carryback period under Section 172(b)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. If you do not make this election with your timely filed return in the NOL year, you are required to carry back the loss to prior years.

Example. In 2014, Robert Jones, the sole proprietor of a small business, has a net operating loss of $66,000. In past years, Jones reported the following amounts of taxable income: in 2012, $82,000, and in 2013, $10,000. The NOL can be carried back 2 years to 2012 and offset $66,000 of taxable income in that year. If Robert anticipates income in 2015, he may prefer to elect to carry forward his loss to 2015 by attaching an election under Section 172(b)(3) to his timely filed 2014 return.

If your income was subject to tax at a lower tax bracket during the carryback period and you expect future income to be subject to tax at a higher tax bracket, you may wish to elect to forgo the carryback of the NOL, and carry it forward instead. This may be especially relevant for net operating losses arising in 2014 since, beginning in 2013, the top marginal income tax rate increased from 35% to 39.6% for higher income taxpayers (i.e., those with annual taxable incomes over $406,750 if filing individually, $432,200 if filing as a head of household, $457,600 if married filing jointly, and $228,800 if married filing separately).

Example. In 2014, Mark’s business incurs an NOL of $20,000. It had been profitable in the 2 previous years, and the profits have been taxed at a 15% tax rate. He expects to generate large income in future years, which will be taxed at the 39.6% top tax rate. By electing to forgo the carryback of the NOL, he can save $4,920 in taxes [$20,000 × (39.6% − 15%)].

For more information on net operating losses, see Form 1045 and Publication 536, Net Operating Losses .

Income reported on Schedule C is classified as self-employment income for sole proprietors, independent contractors, and statutory nonemployees. It is not classified as self-employment income for statutory employees, and is therefore not subject to self-employment tax.

Self-employment tax is calculated on Form 1040, Schedule SE.

The social security tax rate applied to net earnings from self-employment remains at 12.4%.

For 2014, self-employment tax is composed of social security tax of 12.4% and Medicare tax of 2.9%. Under the Affordable Care Act (the comprehensive health care law that was passed in 2010 and upheld as constitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2012), beginning in 2013, an Additional Medicare Tax of 0.9% is assessed on top of the current 2.9% rate—for a total rate of 3.8%—on self-employment income (as well as wages) received in excess of $200,000 ($250,000 for married filing jointly, $125,000 for married taxpayers filing separately). For married couples filing jointly, the additional 0.9% tax applies to the couple’s combined wages in excess of $250,000.

For 2014, the maximum amount of wages and/or self-employment income subject to the social security portion of the self-employment tax is $117,000. All net earnings are subject to the Medicare portion of self-employment tax. Therefore, if your salary income as an employee is $117,000 or above, you would have already paid all the social security tax you owe. Your self-employment income would, however, be subject to the Medicare tax of 2.9% (or 3.8% for taxpayers with higher self-employment income). There is no limit on the amount of earnings subject to the Medicare portion of the self-employment tax. A comprehensive example at the end of this chapter shows how to calculate self-employment tax when you also have salary income.

You may be able to use the short Schedule SE if:

Your self-employment earnings and wages subject to social security were less than $117,000; You did not receive tips reported to your employer; You are not a minister or member of a religious order; and You did not report any wages on Form 8919, Uncollected Social Security and Medicare Tax on Wages. If your net self-employment income multiplied by 0.9235 is below $400, you are not subject to self-employment tax on your self-employment income.

Estimated income taxes. You may be required to pay estimated tax on your self-employment income. This depends on how much income and self-employment tax you expect for the year and how much of your income will be subject to withholding tax.

If you are self-employed but also a salaried employee, you may cover your estimated self-employment tax payments by having your employer increase the amount of income tax withheld from your pay.

For more information, see chapter 4 Tax withholding and estimated tax .

If you have more than one trade or business, you must combine the net earnings from each business to determine your net self-employment income. A loss that you incur in one business will offset your income in another business.

When an individual’s self-employment earnings multiplied by 0.9235 are less than $400, he or she is not required to file Form 1040, Schedule SE, or to pay self-employment tax.

Joint returns. Show the name of the spouse with self-employment income on Schedule SE. If both spouses have self-employment income, each must file a separate Schedule SE. If one spouse qualifies to use Short Schedule SE and the other has to use Long Schedule SE, both can use one Schedule SE. One spouse should complete the front (short form) and the other the back (long form).

Include the total profits or losses from all businesses on Form 1040, as appropriate. Enter the combined Schedule SE tax on Form 1040.

Self-employment tax deduction. You can deduct one-half of your self-employment tax in figuring your adjusted gross income. This is an income tax adjustment only. It does not affect either your net earnings from self-employment or your self-employment tax. To deduct the tax, enter on Form 1040, line 27, the amount shown on line 6 of Short Schedule SE or line 13 of Long Schedule SE and include Schedule SE with your 1040.

In most cases, net earnings include your net profit from a farm or nonfarm business, plus the following items:

Rental income from a farm if, as landlord, you materially participated in the production or management of the production of farm products on this land. Cash or a payment in kind from the Department of Agriculture for participating in a land diversion program. Payments for the use of rooms or other space when you also provided substantial services for the convenience of your tenants. Examples are hotel rooms, boarding houses, tourist camps or homes, trailer parks, parking lots, warehouses, and storage garages. Income from the retail sale of newspapers and magazines if you were age 18 or older and kept the profits. Income you receive as a direct seller. Amounts received by current or former self-employed insurance agents and salespersons that are:Paid after retirement but figured as a percentage of commissions received from the paying company before retirement; Renewal commissions; or Deferred commissions paid after retirement for sales made before retirement. Fees as a state or local government employee if you were paid only on a fee basis and the job was not covered under a federal-state social security coverage agreement. Interest received in the course of any trade or business, such as interest on notes or accounts receivable. Fees and other payments received by you for services as a director of a corporation. Fees you received as a professional fiduciary. Recapture amounts under Sections 179 and 280F that you included in gross income because the business use of the property dropped to 50% or less. Gain or loss from Section 1256 contracts or related property by an options or commodities dealer in the normal course of dealing in or trading Section 1256 contracts. Salaries, fees, and so on, subject to social security or Medicare tax that you received for performing services as an employee. Fees received for services performed as a notary public Income you received as a retired partner under a written partnership plan that provides for lifelong periodic retirement payments if you had no other interest in the partnership and did not perform services for it during the year. Income from real estate rentals, if you did not receive the income in the course of a trade or business as a real estate dealer. This includes cash and crop shares received from a tenant or sharefarmer. Dividends on shares of stock and interest on bonds, notes, and so on, if you did not receive the income in the course of your trade or business as a dealer in stocks or securities.Gain or loss from:The sale or exchange of a capital asset; The sale, exchange, involuntary conversion, or other disposition of property unless the property is stock in trade or other property that would be includible in inventory, or held primarily for sale to customers in the ordinary course of the business; or Certain transactions in timber, coal, or domestic iron ore. Net operating losses from other years. Statutory employee income. If you were a statutory employee, do not include the net profit or loss from that Schedule C (or the net profit from Schedule C-EZ) on Schedule SE. A statutory employee is defined above.

Self-employment tax can be calculated using one of the following methods: the regular method, the farm optional method, and the nonfarm optional method.

Regular Method. Under the regular method, your self-employment tax should be calculated as follows:

Figure your net self-employment income. The net profit from your business or profession is generally your net self-employment income. After you figure your net self-employment income, determine how much is subject to self-employment tax. The amount subject to self-employment tax is called net earnings from self-employment. It is figured on Short Schedule SE, line 4, or Long Schedule SE, line 4a. It is generally 92.35% of net self-employment income. Figure your self-employment tax as follows:If, for 2014, your net earnings from self-employment plus any wages and tips are not more than $117,000 and you do not have to use Long Schedule SE, use Short Schedule SE. On line 5, multiply your net earnings by 15.3% (0.153). The result is the amount of your self-employment tax. If you had no wages or tips in 2014, your net earnings from self-employment are more than $117,000, and you are not required to complete Long Schedule SE (see guidelines at the top of Short Schedule SE), use Short Schedule SE. On line 5, multiply the line 4 net earnings by 2.9% (0.029) Medicare tax and add the result to $14,508 (12.4% of $117,000). The total is the amount of your self-employment tax. If you received wages or tips in 2014 and your net earnings from self-employment plus any wages and tips are more than $117,000, you must use Long Schedule SE. Subtract your total wages and tips from $117,000 to find the maximum amount of earnings subject to social security tax. If more than zero, multiply the amount by 12.4% (0.124). The result is the social security tax due. Next, multiply your net earnings from self-employment by 2.9% (0.029). Multiply the amount of self-employment income (as well as wages) received in excess of the specified threshold amounts ($250,000 for a joint return; $125,000 for a married individual filing a separate return; and $200,000 for all other filers) by 3.8% (0.038). The result is the Medicare tax due. The total of the social security tax and the Medicare tax is your self-employment tax. Optional Methods. Generally, you can use the optional methods when you have a loss or small amount of net income from self-employment and:

You want to receive credit for social security benefit coverage (in 2014, the maximum social security coverage under the optional methods is four credits, the equivalent of $4,800 of net earnings from self-employment); You incurred child or dependent care expenses for which you could claim a credit (this method will increase your earned income, which could increase your credit); or You are entitled to the earned income credit (this method will increase your earned income, which could increase your credit).

The ability to use an optional method of calculating self-employment tax allows you to maintain the benefits of contributing to social security and eligibility for credits based on income even in a down year in your business. In a year where your self-employment earnings are lower, you can use the following optional methods to achieve the result of contributing the maximum amount to social security. Also, an optional method would permit you to take the earned income or child and dependent care credit (depending on eligibility). This benefit is allowed only five times during your lifetime. To be eligible for these methods, net earnings from self-employment must have been $400 or more in 2 out of the previous 3 years and your net nonfarm profits were less than $5,198 and also less than 72.189% of your gross nonfarm income. The optional methods are as follows:

If gross nonfarm income from self-employment is $6,960 or less, report 2/3 of gross income; or If gross income is greater than $6,960, then your net earnings are equal to $4,800. For tax years after 2008, the maximum amount reportable using this method will be equal to the amount needed to get four work credits for a given year. For example, for tax year 2014, the maximum amount reportable using the optional method would be $1,200 × 4, or $4,800.

Start-up expenditures are the costs of getting started in business before you actually begin doing business. Start-up costs may include expenses for advertising, travel, utilities, repairs, or employees’ wages. These are often the same kinds of costs that can be deducted when they occur after you open for business.

Pre-operating costs include what you pay for both investigating a prospective business and getting the business started. For example, they may include costs for the following items:

A survey of potential markets An analysis of available facilities, labor, supplies, etc. Advertisements for the opening of the business Salaries and wages for employees who are being trained and their instructors Travel and other necessary costs for securing prospective distributors, suppliers, or customers Salaries and fees for executives and consultants or for other professional services. Start-up costs do not include deductible interest, taxes, or research and experimental costs. Therefore, subject to other limitations, these items are currently deductible.

The deductibility of your start-up expenditures depends on whether you actually begin the active trade or business.

If you go into business, start-up expenses of a trade or business are not deductible unless you elect to deduct them.

For tax year 2014, the deductible amount of start-up expenditures is the lesser of:

The amount of the start-up expenditures for the active trade or business; or $5,000, reduced (but not below zero) by the amount by which the start-up expenditures exceed $50,000. Any remaining start-up expenditures are to be claimed as a deduction spread over a 15-year period.

All start-up expenditures related to a particular trade or business are considered in determining whether the cumulative cost of start-up expenditures exceeds $50,000. For more information on start-up expenditures, see Publication 535, Business Expenses .

If you have start-up costs in 2014 for a new business exceeding the $5,000 limited amount, you should attach a statement to your tax return electing to amortize the portion exceeding $5,000 ratably over a period of 15 years. Complete and attach Form 4562, Depreciation and Amortization, for start-up expenses you are beginning to amortize in 2014.

Example. Tony’s repair shop started business on June 4, 2014. Prior to starting business, Tony incurred various expenses totaling $11,000 to set up shop. Tony can deduct $5,000 of these expenses in 2014 and deduct the balance of $6,000 ratably over 15 years.

Although the IRS has been instructed to do so, no guidance has been issued as to when a trade or a business begins. When it does so, the IRS is likely to take a conservative stance. In the meantime, there has been substantial litigation about this issue. The generally accepted rule seems to be that even though a taxpayer has made a firm decision to enter into a business, and over a considerable period of time has spent money in preparation for entering that business, he or she still has not engaged in carrying on any trade or business until such time as the business has begun to function as a going concern and has performed those activities for which it was organized.

Failure to go into business. If an attempt to go into business is not successful, your ability to deduct the expenses incurred trying to establish your business depends on the type of expenses incurred.

Investigatory expenses. The costs incurred before making a decision to acquire or to begin a specific business are classified as personal and therefore are not deductible. Investigatory expenses include costs incurred in the course of a general search for, or preliminary investigation of, a business prior to reaching a decision to acquire or enter any business. Examples include: expenses incurred for the analysis or survey of potential markets, products, labor supply, transportation facilities, and so on.

Start-up expenses. The costs incurred after making a decision to acquire or to establish a particular business, and prior to its actual operation, are classified as capital expenditures and may be deductible in the year in which the attempt to go into business fails, if prior to the end of the amortization period.

Business sold. If you completely dispose of a trade or a business before the end of the amortization period you have selected, any deferred start-up costs for the trade or business that have not yet been deducted may be deducted to the extent that they qualify as a loss from a trade or a business.

Every taxpayer must determine taxable income and file a tax return on the basis of an annual accounting period. The term “tax year” is the annual accounting period you use for keeping your records and for reporting your income and expenses. The accounting periods you can use are as follows:

A calendar year A fiscal year A tax year is adopted when you file your first income tax return. It cannot be longer than 12 months.

Calendar tax year. If you adopt the calendar year for your annual accounting period, you must maintain your books and records, and report your income and expenses for the period from January 1 through December 31 of each year.

Fiscal tax year. A regular fiscal tax year is 12 consecutive months, ending on the last day of any month except December.

If you adopt a fiscal tax year, you must maintain your books and records, and report your income and expenses using the same tax year.

If you filed your first return using the calendar tax year and you later begin business as a sole proprietor, you must continue to use the calendar tax year, unless you get permission from the IRS to change. You must report your income from all sources, including your sole proprietorship, using the same tax year.

Accounting methods are described in chapter 1 Filing information . The discussion that follows relates mainly to self-employed entrepreneurs, sole proprietors, and others who file Schedule C.

No single accounting method is required for all taxpayers. Generally, you may figure your taxable income under any one of the following accounting methods:

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue

15 Circular E, Employer’s Tax Guide

15 Circular E, Employer’s Tax Guide 15-A Employer’s Supplemental Tax Guide

15-A Employer’s Supplemental Tax Guide 225 Farmer’s Tax Guide

225 Farmer’s Tax Guide 334 Tax Guide for Small Business

334 Tax Guide for Small Business 463 Travel, Entertainment, Gift and Car Expenses

463 Travel, Entertainment, Gift and Car Expenses 535 Business Expenses

535 Business Expenses 541 Partnerships

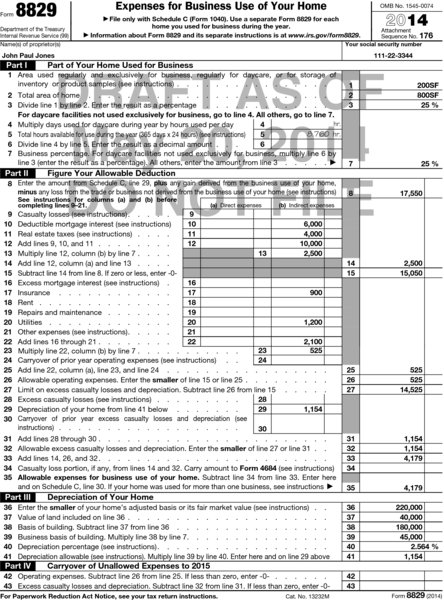

541 Partnerships 587 Business Use of Your Home (Including Use by Day-Care Providers)

587 Business Use of Your Home (Including Use by Day-Care Providers)