8 Billing Schemes

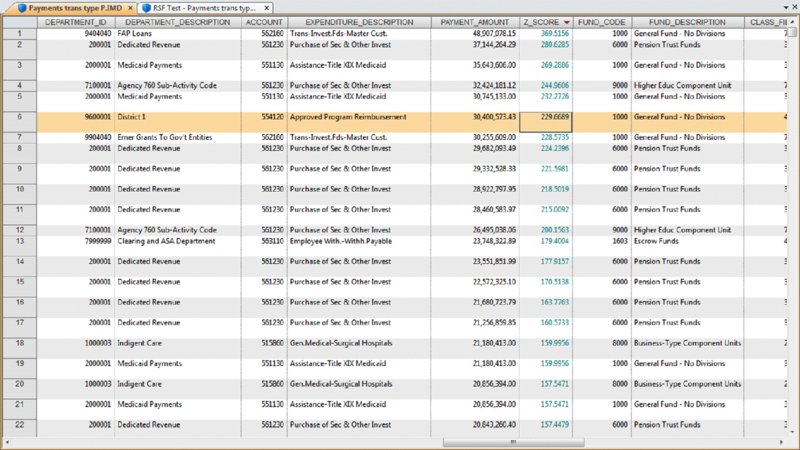

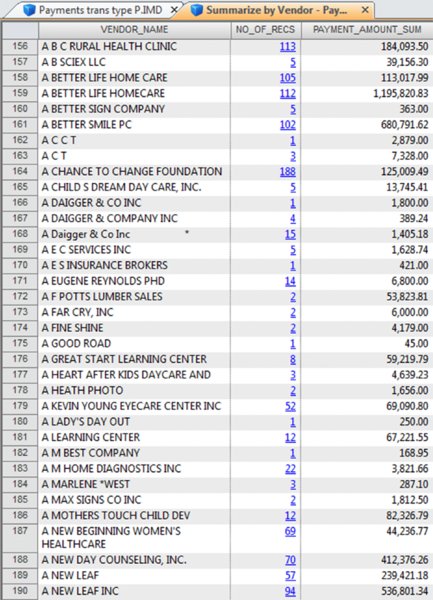

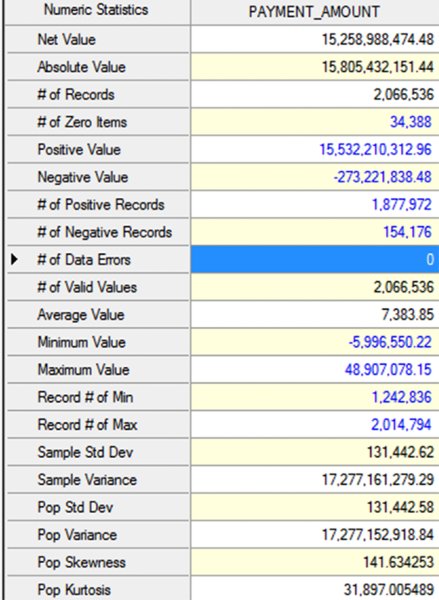

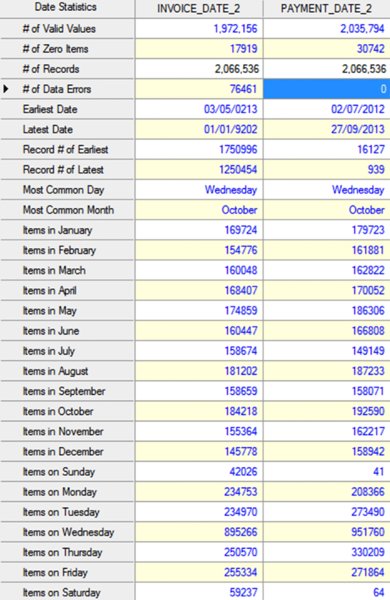

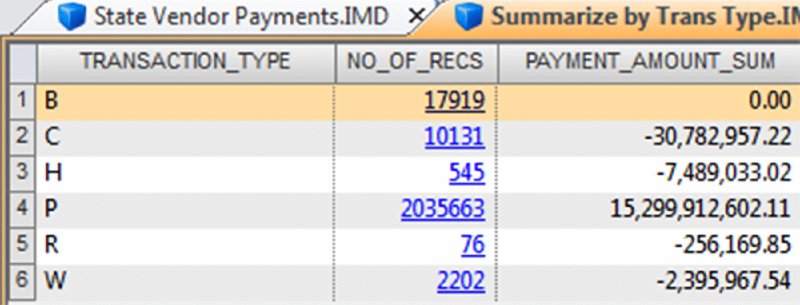

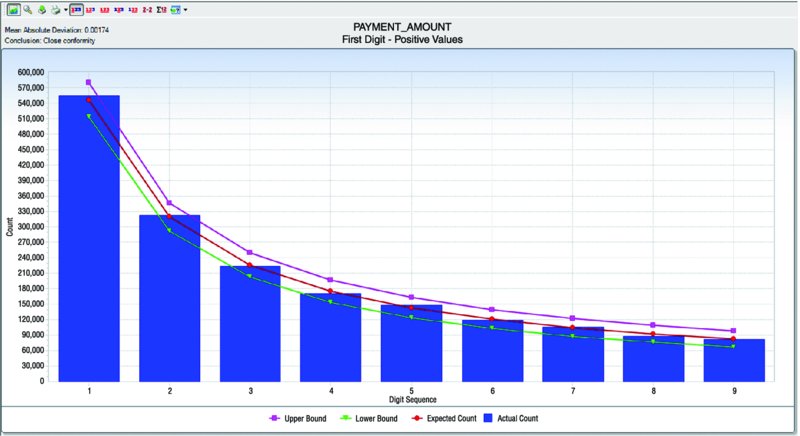

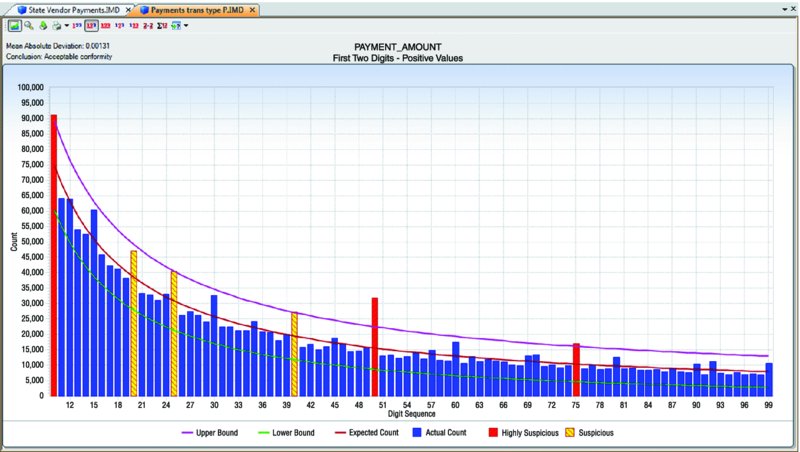

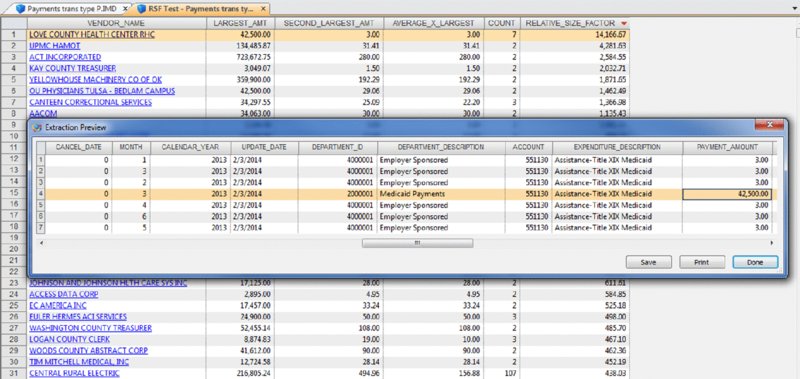

CHAPTER 8 BILLING SCHEMES ARE PERPETRATED on the business through the accounts payable department. Businesses incur liabilities through the normal course of business that must be settled within a certain time period. Almost all expenditures made by the company are processed by accounts payable. The majority of the payments would be for trade payable and expense payable accounts. Trade payables are for the purchases of goods that are normally recorded as inventory and as part of the cost of goods sold. Expenses payable are those spent for purchases of goods or services that are normally expensed. Travel and entertainment expenses are also typically handled by accounts payable. Payments flow through the system in the same manner, whether they are legitimate or fraudulent. Since so many transactions go through accounts payable and are the largest outlay for most organizations, you need to be vigilant to detect bogus payments. Not only is fraud of concern, but errors and inefficient payment processing are also issues, and all are costly to organizations just the same. Errors may be duplicate payments made or unnecessary charges paid for. Inefficient processing may include unnecessary payments for late payment interest or fees, discounts for earlier payment not taken, or individual payments of multiple invoices to the same provider during the same period. There are a number of ways to run a billing scheme. The costliest to the organization are those where the corrupt employee forms a company for the purpose of receiving illegitimate payments. The company is formed so that the transaction flows are the same as a legitimate business, but the company has not provided goods or services invoiced to the targeted business. Normally the fraudulent invoices would be for services, as services eliminate involving the receiving department for goods. Where the billing of goods is involved, collusion from the receiving department or warehouse is needed to verify the receipt of fictitious shipments. However, there would be an inventory issue that needs to be covered by means of falsifying inventory counts or by setting up a method of writing the goods off. For goods, the intermediary scheme is simpler and less risky to implement. The corrupt purchasing employee, rather than purchasing directly from the vendor, would have his own intermediary company make the purchase and resell it to the employer at inflated prices. A company is formed; a bank account is set up; and sometimes a post office box is used to receive the payments. When a false invoice is submitted to the organization, the corrupt employee, if in the right position, would authorize the payment of the invoice. If the employee cannot authorize the payment, then he or she may bring it to someone who is overly trusting to sign the authorization. Alternatively, the corrupt employee could just forge an authorization signature. Once the first payment goes through the accounts payable system, subsequent payments are simpler. The vendor by then is already added to the vendor master file as a supplier. Where there are strong controls over adding new vendors to the master file, the fraudster can form a company with the name similar to that of an existing vendor. An inactive vendor still on the vendor master file would be preferred so that only the address where the payment is to be sent needs to be changed. Where there are strong controls over the automated flow of payments, there may be weak controls over manual payments. The corrupt employee will cause some deliberate error in the payment process so that the process is disrupted and manual intervention is necessary. This allows an opportunity for the employee to take control of the payment process to their benefit. There are also overpayments, duplicate payments, and paying the wrong vendor schemes. These schemes involve making deliberate errors and paying legitimate vendors excess funds. The corrupt employee calls and asks those vendors to return the check or the excessive payment back directly to them for conversion to their own account. Schemes that have the organization purchase goods benefiting the corrupt employee may be personal items paid for by the organization or supplies used for the corrupt employee’s side business or for resale. These are not goods that the organization requires in their regular business operations so it is not classified as theft. The corrupt employee caused the organization to pay for items not needed so it is considered a billing scheme. If the employee cannot authorize the purchases, then the fraudster has to take additional steps, such as getting a supervisor to sign a purchase requisition so a purchase order can be sent to the vendor. Signatures can be forged and purchase orders can be inserted into the purchasing cycle depending on the corrupt employee’s position in the organization. For accounts payable data analytical tests, we will mainly be using a large data set downloaded from the state of Oklahoma’s website.1 The data set is the state of Oklahoma Vendor Payments Fiscal Year 2013, which contains over 2 million records from the different agencies in Oklahoma. There are 29 fields, of which 15 are relevant to our discussion: Where this payment file is not appropriate for demonstration purposes, the sample files that are included with the IDEA software or IDEA course material will be used. To get an overall view of the data contents of the “State Vendor Payments” file, we review the field statistics. Of the numeric fields, only the PAYMENT_AMOUNT field provides any interest, as shown in Figure 8.1. Figure 8.1 Field Statistics of Payment Amount We note that all 2,066,536 records have valid values in this field but 34,388 of them contain the amount of zero. There is a wide spread among the data amounts, ranging from a negative $5,996,550.22 to a positive value of $48,907,078.15. To obtain a better insight of the amounts, you should perform a stratification of the PAYMENT_AMOUNT field. More interesting are the field statistics for the INVOICE_DATE_2 and the PAYMENT_DATE_2 fields. We can see that the INVOICE_DATE_2 field contains 76,461 errors and that there are issues with date inputs, as can be seen in both the record number of the earliest and of the latest dates as displayed in Figure 8.2. Figure 8.2 Field Statistics of Dates The PAYMENT_DATE_2 field appears to be reliable. There are no data errors and the dates seem to be in line with what is expected. Of special interest are the 41 payments made on Sundays and the 64 payments made on Saturdays. Both the INVOICE_DATE_2 and the PAYMENT_DATE_2 fields contain zero or were originally blank in these fields of 17,919 and 30,742 respectively. Summarizing on TRANSACTION_TYPE tells us that our main focus should be on type P, as they appear to be payments actually made. See Figure 8.3. Figure 8.3 Transaction Types From the review of the data the following are noted: We are not sure of all the coding as the data file was downloaded from an Internet public source. From the “State Vendor Payments” file, we can extract to a new file called “Payments trans type P” by using the equation of TRANSACTION_TYPE = P. We can check to see if the data set conforms to Benford’s Law. For Benford’s Law, we will test on where TRANSACTION_TYPE are P or payments and on positive values. For the high-level first digit test, the resulting graph shows high conformity in Figure 8.4. We can then select the first two digits for a better precision analysis. Figure 8.4 Benford’s Law First Digit Test for Payment Amounts There is acceptable conformity in Figure 8.5. While it is not unusual for the first two digits test for all the digit pairs not to meet the expected count, on the whole the data set conforms. However, it would be prudent to examine some of the contents of the highly suspicious and suspicious numbers. Figure 8.5 Benford’s Law First Two Digits Test on Payment Amounts For the last two digits test shown in Figure 8.6, there is close conformity for almost all the numbers with the exception of 0 and 50, which in reality is normal, especially for numbers ending with zero. Figure 8.6 Benford’s Law Last Two Digits Test Since the data set as a whole conforms we can accept the Benford’s Law results or we can apply the tests on specific individual agencies. If a specific agency is selected for a detail review, then all the general tests can be reapplied just to the payments associated with that specific agency. This data set contains many high-dollar-payment amounts. There are 1,590 records where the paid amounts were $1 million or more. To see these high-dollar records, we simply index the PAYMENT_AMOUNT field in descending order. The largest amount of almost $49 million was paid to a Protected Information vendor name. Many of the top amounts exceeding $20 million were paid to JPMorgan Chase Bank for the purchases of securities and other investments. It is unlikely in our general review that these high-dollar amounts would be of significant interest, unless we were auditing investment transactions or focusing on payments to banks. What we are interested in are unusually high payments to individual vendors. We could employ the Top Records feature of IDEA to extract a user-specified number of the top-most amounts for each vendor. However, we would have to examine all the vendors. There are many vendors in this payment file. Our objective is to review, by vendors, where the largest amount paid is significantly higher than the next highest amount. High differences can signify errors or fraud. To make reviewing details easier, in the resulting Relative Size Factor test file, we use the Defined Action Field feature on the VENDOR_NAME linked to the payment file. We can then just click on any of the vendor names to obtain an extraction preview for the selected vendor. As an example, we will look at the transactions of the incredibly high RSF ratio of the first vendor displayed. All records had payments of $3.00 each while the largest records showed a payment of $42,500.00, shown in Figure 8.7. Figure 8.7 Relative Size Factor Test of Payments by Vendor Names You can then select other high-RSF ratios, such as Central Rural Electric in record number 31, to examine in more detail. There were 107 transactions with average amounts of $156.88 if the largest number of $216,805.24 was excluded. Applying the Z-score test on the entire payment file and indexing the Z_SCORE field by descending order, we can see from the score how much the amount deviates from the center amount shown in Figure 8.8. Figure 8.8 Z-Score Test of All Payments While useful, the Z-score test is more effective when applied to certain classes such as on a specific agency or specific vendor. Let’s summarize by vendor to select some to apply the Z-score test to. The new summarize file is named “Summarize by Vendor—Payment.” Since we do not have vendor numbers and are relying on vendor names, in Figure 8.9, we note that there may be issues with how the names are entered. This should be kept in mind when applying additional tests later. For instance, record 158 and 159 are likely the same vendor. Similarly, records 189 and 190 are the same vendor. Figure 8.9 Summarizing by Vendors’ Names We will combine the vendors A Better Life Home Care with A Better Life Homecare and then apply Z-score to both as if they were one vendor. The new file can be called “A better life home care—combined.”

Billing Schemes

DATA AND DATA FAMILIARIZATION

DATA AND DATA FAMILIARIZATION

BENFORD’S LAW TESTS

BENFORD’S LAW TESTS

RELATIVE SIZE FACTOR TEST

RELATIVE SIZE FACTOR TEST

Z-SCORE

Z-SCORE