1922

1922

I am young, I am twenty years of age; but I know nothing of life except despair, death, fear, and the combination of completely mindless superficiality with an abyss of suffering. I see people begin driven against one another, and silently, uncomprehendingly, foolishly, obediently and innocently killing one another … Our knowledge of life is limited to death. What will happen afterwards? And what can possibly become of us?1

– Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front

This is a book about a book and how it still speaks to us. It is also a book about a time and how it still resonates in us. The year is 1922: the year that D.H. Lawrence wrote Kangaroo and that T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland and James Joyce’s Ulysses were both published. So too was Max Weber’s posthumous masterpiece Economy and Society.2 The same year Mikhail Bakhtin first embarked on his great work on the history of the novel. With the publication of Political Theology, Carl Schmitt dramatically changed his direction and cast his die. Mussolini seized power. Something unusual was in the air in 1922; something fevered and intense and gravely troubled. This was not unusual for Lawrence – he was always fevered and intense and gravely troubled. But for just a moment Lawrence stood on the same side of history rather than grimly against it.

This chapter is in three sections: first, I will say something about the dimensions of the crisis of thought and feeling which the end of the First World War aroused and to which the many creative works in the immediate post-war period were a distinctive reaction. In the next section I hope to show how this crisis related not just to questions of art and culture but to questions of law and politics – in particular to a reaction to the problem of legal judgment strongly tinged by romanticism and invested with an alternative version of modern legal history. Indeed, as has been ably established, in Weimar Germany the early 1920s was a remarkable intense period for the legal and political theory which is central to this book.3 In 1920 Hans Kelsen’s major work on sovereignty and law appeared. Walter Benjamin’s ‘Critique of Violence’ followed in 1921, along with Carl Schmitt’s The Dictator. In the final section I will focus on Schmitt’s 1922 work Political Theology in which he took on all three of these works (including his own).4 All these books address the relationship between political authority and legal judgment, and the limits or otherwise imposed by the latter on the former. Carl Schmitt’s uncompromising rejection of the liberal rule of law can be seen in terms of both this wider legal historiography and the post-war crisis that it mirrored. In Chapter 4 I want to situate Lawrence in relation to this crisis and propose his novel Kangaroo as our guide to it and through it. Chapter 5 will return us to the question of the rule of law and attempt to demonstrate that, in uncannily similar ways, the crisis of the early twentieth century has not yet been resolved. That will set the stage for my effort in the remainder of the book to present Lawrence’s writing, particularly in Kangaroo and his other works from that time, as a striking response to the most important problems of his time.

Modernism and the crisis of modernity

What was in the air in 1922 was modernity, modernism and the modern. Now these are all sweeping terms whose use is contentious and divergent. Their periodicity and their relevance take on quite different inflections in different places, cultures, disciplines, and arts. Modernity might be said to encompass the monumental changes in society and in belief that the Enlightenment set in motion and that accelerated and ramified with the industrial revolution right through the nineteenth century.5 Modernism is by no means merely the affirmation of these changes. On the contrary, it refers to the paroxysms which ensued when the worlds of the arts and ideas began to depict, understand, and respond to them. Some would date modernism as early as the publication of Rimbaud’s Un Saison en Enfer in 1873, with its ruthless rejection of romance and its ringing final sentence: ‘One must be absolutely modern’.6 Well before the First World War, certainly, Sigmund Freud and Henri Bergson, Cézanne, Malevich, Kandinsky and the Blue Rider School, Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite and Rite of Spring and Schoenberg’s Second String Quartet had all broken with key tenets of aesthetic and social convention. Virginia Woolf famously wrote that ‘on or about December 1910, human character changed’.7 In the teens of the new century, cubism and dadaism further accomplished in aesthetic terms the fracturing of the previous century’s social and class stability – even complacency – to which Woolf alludes. Meanwhile, in a few short years, starting perhaps from the failed Russian Revolution of 1905, political turmoil had pulverised the empires of Europe with the force of an imploding star. In different ways all these events challenged the normative assumptions and framework of the European establishment, its blithe progressivism and its arrogant imperialism. In modernism we see how the forces of modernity (including its secularism, its industrialisation, its specialisation, its rationalism) steadily undermined the authority of God and government, the neutrality and logic of science and reason, and the objectivity of representation – in painting, in literature, in music, in philosophy, in psychology, and in politics no less.

Now the response of artists and thinkers to these transformations and doubts was not uniform. For some this shattering of established ways of knowing or being was a matter of description, for others it provoked invention or celebration, mourning, fear or nihilism. The expressionists seem to respond with despair to this new world; the futurists and the constructivists embraced it as a land of unfettered imaginative possibility; the dadaists, cubists and modernist writers with a certain whimsy. But regardless of their affective orientation, certain key features emerge. Modernism signifies a commitment to individual over social good, a sense of rootlessness and exile, and, coupled with an emphasis on the varieties and uncertainties of individual subjectivity, the most comprehensive critiques of representation and the most radical experiments in form.8 Again Rimbaud presaged much that was to follow when he wrote Je est un autre.9 The fractured subjectivity, the formal inventiveness, the linguistic restlessness, the uncertain searching that lies close to the heart of all his poetry seems not far from the mark.

Modernism represented and was a response to ‘the shock of the new’.10 Both were traumatically intensified by the Great War. Throughout Europe (and again with quite different implications in different countries) the Great War was an infected wound that gave the lie to the previous century’s conceit that European civilisation had triumphantly united the forces of reason, science and humanity. Easier said than done. As Paul Fussell writes, even the grandiloquent names of the War’s noble-sounding ‘battles’ – the Somme, Verdun, Paschendaele, Gallipoli and the rest – merely disguised, beneath the illusion of their continuity with past military exploits, the tragedy of a loss of life that was at once unfathomable, banal and futile.11 The power of Erich Maria Remarque’s classic record of his experiences in the War, All Quiet on the Western Front, does not lie in his depiction of the violence and pain of war, but in the powerful way in which he depicts its timeless futility. An abyss without purpose faced all those who went to die and to watch others die.12 What was glorious about leaving millions of men to rot in foetid trenches year upon year, periodically slaughtering them for notional gains (well over a million casualties on the Somme, over 60,000 on the first day alone)?13 Did the logic of reason allow this? Did the power of technology enable it? Was this what religion sanctified, what democracy supported, where civilisation led?

Shells, gas clouds and flotillas of tanks – crushing, devouring, death.

Dysentery, influenza, typhus – choking, scalding, death.

Trench, hospital, mass grave – there are no other possibilities.14

The British war poets had seen all this, none more so than Wilfred Owen, who in a shocking reversal of the story of Abraham and Isaac, imagined the War as the betrayal of young men by their elders:

Then Abram bound the youth with belts and straps,

And builded parapets and trenches there,

And stretchèd forth the knife to slay his son.

When lo! an Angel called him out of heaven,

Saying, Lay not thy hand upon the lad,

Neither do anything to him, thy son.

Behold! Caught in a thicket by its horns,

A Ram. Offer the Ram of Pride instead.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.15

There is something appalling not just in the image of wilful arrogance conjured by this poem, but in the relentless logic which continues to play itself out, blindly destroying its own seed not all at once but ‘one by one’. And a pall likewise hangs over all of post-war poetry. In T.S. Eliot’s Wasteland and Ezra Pound’s Cantos, the smoldering ashes of our illusions hang like ‘smoke over Troy’.16

The Great War had traumatically shown that the problem of the modern world lay in man, and that a greater knowledge of it, a greater organisation of it, a greater technological competence, was likely to do more harm than good. The War came to a world of moral and technological over-confidence, unmasking its inner contradictions and its hollow rhetoric. Ernest Hemingway wrote that ‘abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene besides the concrete names of villages’.17 The War was the final and resounding blow struck against the naïve faith of modernity in its systems, ideology and leaders:

They were supposed to be the ones to help us eighteen-year-olds to make the transition, who would guide us into adult life, into a world of work, of responsibilities, of civilized behavior and progress – into the future … In our minds the idea of authority – which is what they represented – implied deeper insights and a more humane wisdom. But the first dead man that we saw shattered this conviction … And we saw that there was nothing left of their world. Suddenly we found ourselves horribly alone – and we had to come to terms with it alone as well … Our knowledge of life is limited to death. What will happen afterwards? And what can possibly become of us?18

Much later, of course, George Orwell wrote of all this as the emerging conflict between technology and humanism: of the problem of social relatedness in the era of scientific progress, of the deadening effect of industry, rationality and positivism on art, emotion, and community.19 Max Weber, too, in the last few years before he died in 1920, became increasingly disillusioned with the implications of the rationalist and specialised tendencies of the West that he had done so much to identify. His later works and lectures seem to call for the revival of an ‘ethics of conviction’ and even extolled the necessity of a kind of charismatic leadership which he had previously characterised as irrational.20 In his posthumous Economy and Society, also published in 1922, Weber defines modernity in terms of a shift from normative to instrumental modes of social action and justification, but paints a distinctly bleak picture of a ‘polar night of icy darkness’ in which the increasing rationalisation of human life traps individuals in an ‘iron cage’ of rule-based controls.21

Rational calculation … reduces every worker to a cog in this bureaucratic machine and … he will merely ask how to transform himself into a somewhat bigger cog … This passion for bureaucratization drives us to despair.22

Indeed, by 1917 ‘the crisis of modernity’ was already shorthand for a comprehensive loss of faith in the foundations of the modern world. R.G. Collingwood that year wrote of the ‘crisis of civilization’ as a rupture, catastrophically magnified by modernity, in the framework of logical positivism that ‘belittles what one cannot share and destroys what one cannot understand’.23 George Simmel’s final lecture, delivered shortly before he died in war-torn Strasbourg in September 1918, likewise spoke of the deep-seated ‘conflict of modern culture’ between life and form, rigidity and flow, rules and experience, in which the classical impulse to prioritise form as such is rejected root and branch.24 ‘Life, in its flow, is not determined by a goal but driven by a force’, he wrote, while the guns of the Western front continued to bring home the depth of the error we make in treating the latter as if it were the former.

In sociology as in poetry, philosophy as well as literature, the crisis of modernity articulated a widespread loss of conviction in moral, religious or social certainty. The forces of materialism and industrialisation had exposed the illusory conceits of these alternative creeds without replacing them. This was what Weber meant by the ‘disenchantment of the world’:25 the German word Entzauberung suggests the end of magical thinking. How else to explain the obsession of the late and post-Victorians with séances and mediums and ghosts, or the bizarre fairy-mania which, immediately after the War, led the Theosophical Society and well-known figures like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to treat as genuine ‘spiritual emanations’ photographs of fairies – quite obviously cut-outs from a picture book – cavorting with two girls in an arcadian scene? Conan Doyle, the father of Sherlock Holmes, that shining light of Victorian rationality, published The Coming of the Fairies in 1922.26 How are we to explain such delusions except as the last desperate efforts of a society to find evidence of a mystical reality, to turn back from the corruption of the War to a radical and fantastic ignorance masquerading as innocence?27

In E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India (1924), the ambiguous and traumatic events of the Marabar Caves give a palpable physical dimension to this psychic crisis:

[Mrs. Moore] had come to that state where the horror of the universe and its smallness are both visible at the same time – the twilight of the double vision in which so many elderly people are involved. If this world is not to our taste, well, at all events there is Heaven, Hell, Annihilation – one or other of those large things, that huge scenic background of stars, fires, blue or black air. All heroic endeavour, and all that is known as art, assumes that there is such a background, just as all practical endeavour, when the world is to our taste, assumes that the world is all. But in the twilight of the double vision, a spiritual muddledom is set up for which no high-sounding words can be found; we can neither act nor refrain from action, we can neither ignore nor respect Infinity. Visions are supposed to entail profundity, but – Wait till you get one, dear reader! The abyss also may be petty, the serpent of eternity made of maggots …28

In short, Mrs Moore lived in a world she no longer knew or understood. In the forbidding and disorienting caves, she found she could no longer rely on either a mundane or a sublime compass. On the precipice of the twentieth century, Moore lost her moorings, and heard only the echoes of a deep nothingness.

The great romantics such as Wordsworth or Coleridge believed that imagination ‘reveals itself in the balance of reconciliation of opposite or discordant qualities … rich in proportion to the variety of parts which it holds in unity’.29 I suggest that the War had trampled that amiable dream of harmony or synthesis – of the overcoming of difference and conflict between peoples and between, say, art and science – once and for all. Thus the two visions that had underpinned the previous century – the materialist vision of mechanical and rational progress, and the romantic or immaterialist vision of harmony and balance – could be neither sustained nor reconciled. The result was a widely felt sense of ethical and social free-fall.30 The nineteenth-century novel, for example, had operated under an implied compact which granted the narrator an omnipotent knowledge and the depiction of a single and objective reality, in exchange for an ultimate resolution. In short, sense and sensibility: literature as a social science. A great deal of writing in law and literature still assumes this world-view, with its insistence on an aesthetic pleasure which attests to social reality. But the Great War struck it dead – destroyed literature’s over-confident regard for its own universality, objectivity, order and completeness. Instead, literary modernism moved in another direction. It began to pursue a wary obsession with the deep subjectivity and incommensurability of individual voices and perspectives, and can be seen as part of this same pattern of fraught response to and disenchantment with the promise of order, rules, reason and progress. The great modernist texts of the post-war period, not just Ulysses and The Wasteland of 1922 but also, for example, To the Lighthouse, seek a new accommodation amongst these terms in a faithless and fallen world. These works reveal a struggle, not just in the world but in their authors as they try to find a voice and to make sense of the world. Dickens, Eliot, Trollope, Balzac, Tolstoy and the rest are too confident, too objective, altogether too omniscient for that; whatever failings or incomprehension they explore are their characters, not their own.

The vertiginous disenchantment, external and internal, physical and psychological, brought on by the menacing failure of the promise of rationalism and the promise of romanticism can perhaps be seen most clearly in the emotional and subjective phenomenology of Expressionism. There is a line of affective horror which leads from Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) right up to the work of German post-war artists like George Grosz, Egon Schiele and Otto Mueller. Otto Dix, notably, experienced and documented modern warfare during his years as a machine gunner on the Western Front. He combined chillingly realist portrayals of it with a Nietzschean ecstasy in the primal liberation from conventional morality which the modern War unleashed.31 His great series of war-time etchings, Der Krieg, exposed the reality of modern warfare with a clinical eye. In Der Schutzengraben or Trench (1920–23)32 and later works on the same motif, the depiction of atrocity is fused with an hallucinatory sublime, as if the romantic landscapes of Caspar Friedrich were constructed out of a mountain of corpses. Taken together these works helped to destroy forever the romantic illusions of soldiering that had held sway in the European imaginary for a thousand years. But what was to replace them?

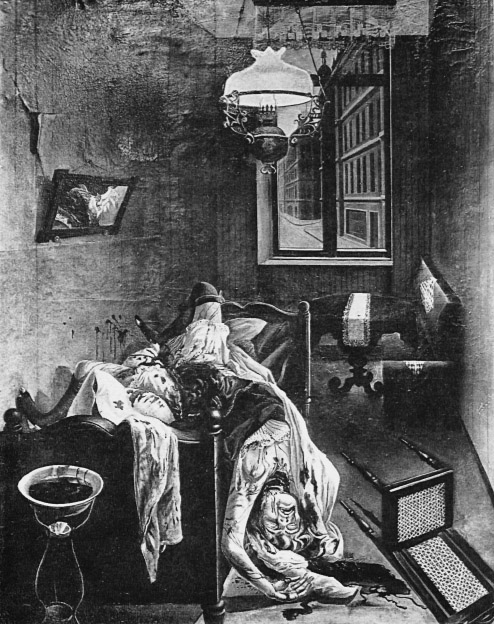

In Lustmord (1922) – indeed there are three works about ‘sex murder’ from that year alone – the personal implications of the Great War’s violence and degradation, its objectification, mechanisation and alienation, are brought home in the most intimate and pitiless fashion. Dix’s work does not aim to depict the pained psychology of the post-war world, but rather through this disturbing

objectivity to produce it. He stands as the prophet of a new era, in which all the old connections between nations, morals, responsibilities and norms have been (as Lawrence would say) reduced to dust. Dix’s ‘new objectivity’ exposes the desolation, alienation and degradation of modernity, along with the terrifying liberties of a world endowed of such capacities and shorn of all anchors or limits.

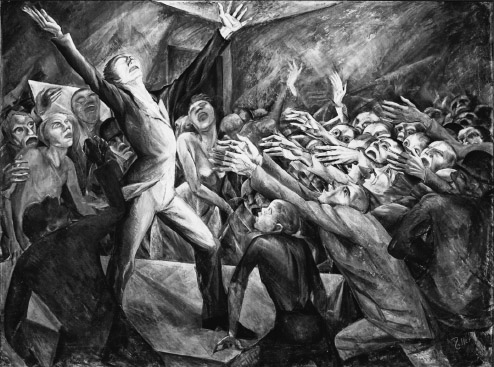

In La Valse (1920), another masterwork of post-war modernism, Maurice Ravel challenges us to wonder whether the most romantic of nineteenth-century musical forms – the most progressive, the most elegant, the most civilised – could still be taken seriously. The intense irony of Ravel’s music lies in its juxtaposition of older forms and traditions with modernist disenchantment. As the waltz swirls faster and faster, increasingly manic and out of control, the sense of contradiction becomes ever stronger, until finally the effort of sustaining the illusion of such a world brings the whole edifice crashing down. The metaphor of dance is not inapt in its implications of movement without progress. Schoenberg described his fractured music as ‘a death dance of principles’.35 And here is Klaus Mann:

The stock market danced. The members of the Reichstag hopped about as if mad. The poets were convulsed with rhythmic spasms. The cripples, the prostitutes, the beggars, the reformers, the retired monarchs and astute industrialists – all of them swayed and skipped. They danced the shimmy, tango, fox trot and St Vitus’ dance. They danced despair and schizophrenia and cosmic divinations.36

In the aftermath of the War, and in every sphere, the crisis of modernity and the question of positivism and its ‘other’ were imbued with an intense and panicked urgency. In every sphere the disorienting loss of faith in both this world and the next, the human and the divine, in reason and in love, was crucial. The great writers of modernism were united in their sensitivity to the death dance of principles around them.

Lawrence was by no means alone in his interdisciplinary interest in these questions or in perceiving the connections between all these spheres.37 But Kangaroo is an unusually ambitious attempt to engage with literary, political and psychological modernism all at once. Lawrence was the canary of the crisis, uniquely sensitive to its many registers. For Lawrence was a child of romanticism; it told in his intellectual formation, notably in the time he spent in Germany before the War, but equally in his social and religious background. Like Nietzsche, he was the rebellious son of a family of Dissenters and, throughout his early work, the threads of a communitarian and millenarian spirit are everywhere apparent. ‘Down among the uneducated people’, Lawrence wrote about his own upbringing, ‘you will still find Revelation rampant’.38 The Rainbow portrays the intimacy of working-class communities and the weight of the modern world as it bears in on them. In its metaphors and style it exhales the rhythms of the Bible and the immanence of a mighty God. Lawrence was deeply religious and yet this foundation was being swept away from beneath his feet. Lawrence was also deeply English and – as we will see and as Kangaroo addresses quite specifically – this too was taken from him. The Englishman became the exile, the preacher’s son the pantheist. What is interesting is not just that Lawrence made those choices but what it cost him to make them. If the crisis of modernity was a loss of the foundations of the known world then he is emblematic not just in communicating for us exactly what this catastrophe felt like but in the deeply personal manner in which it affected him.39

Although Anne Wright identifies Women in Love as Lawrence’s ‘crisis book’, it was merely one moment in his on-going and deepening search for some new moorings to save him from the rudderless impasse of modernity. The need to find a deeper and truer order than that provided by modern civilisation and which can be linked to something like spiritual and temporal love, certainly haunts both The Rainbow (1915) and Women in Love (1916). But without doubt his experiences in the last years of the War profoundly intensified this sense of loss; it would take him five years, until he wrote Kangaroo, to come to terms with it. In a letter written in 1917 he wrote, ‘I feel as if the whole thing were coming to an end – the whole of England, of the Christian era … The world is gone, extinguished, like the lights of last night’s Café Royal’. And in another, written to Lady Ottoline after witnessing the Zeppelin raids on London (a passage which eventually found its way into Kangaroo), he sees the technological violence of the twentieth century as auguring a total erasure: ‘So it seems our cosmos is burst, burst at last, the stars and moon blown away … So it is the end – our world is gone, and we are like dust in the air’.40 In 1918 he wrote to his friends the Garnetts:

I suppose you think the war is over that we shall go back to the kind of world you lived in before it. But the war isn’t over. The hate and evil is greater now than ever. Very soon war will break out again and overwhelm you. It makes me sick to see you rejoicing like a butterfly in the last rays of the sun before the winter … Europe is done for.41

The War years ‘changed his life forever’.42 Not because it gave him a hatred of the mob and democracy (he already had that) but because it radically undermined his ability to believe in any structures, principles or ideologies at all. Lawrence was in fact one of the very first writers to see that the end of the Great War was only the beginning of the terrible problems that this loss of belief and this truly desperate search for an alternative way of thinking about politics, justice and personal relations would engender in the years to come, and of which the looming battles between fascism and communism were merely symptoms.

The romantic turn

Reactionary modernism

After the War, one notable response was therefore to turn one’s back on mechanical modernity and adopt a renewed and uncompromising romanticism. In Lawrence’s work, not least in the early parts of Kangaroo, we can see the threads which connected him to the writers and philosophers from the German tradition in which he was immersed,43 no less than to the millennial and eschatological religious tradition of radical Inner Light hermeneutics that had been central to Lawrence’s upbringing: apocalyptic, ‘right-angled’, and committed to ushering in a new world of unity and perfection, of love not of law.44 This religious feeling, as M.H. Abrams and others make clear, was itself central to the origins and structuring architecture of romantic thought.45

Now as I previously noted, romanticism can be understood in terms of the search for a lost unity of purpose and in the reconciliation or synthesis of opposites. This led, so Schmitt argued, to a purely aesthetic response to conflict or difference, a ‘metaphysical narcissism’,46 and a chronic inability, faced with the reality of conflict, to take decisive action. But from the turn of the century, in a world which increasingly seemed to be losing its connection to nature, art and tradition, the search for a new harmony, a new Eden or a new Jerusalem,47 very often took the form of a deep antagonism to modernity. The romantics are thus increasingly distinguished by the opposition of art to science, feeling to reason, pre-modern to modern ideals, and the soul to the material world. This is how Leo Strauss explained it: