18 REMEDIES

CHAPTER 18

REMEDIES

INTRODUCTION

In the majority of disputes arising from a contract, it is clear that self-help remedies will most often be resorted to before the injured party considers their formal legal remedies. Self-help remedies have a number of economic advantages. They are cheaper, informal and quick. In the everyday world of business, they may also produce a powerful incentive to perform. Complaints and threats to reputation, the holding of the other party’s belongings and realisation of a ‘security’, all pose a considerable risk to those who claim legitimate breach or hope that an illegitimate breach will not be actioned because of the financial consequences. These factors provide an important backdrop to our consideration of formal remedies and will continue to be relevant as we move on to a consideration of whether or not litigation is the appropriate dispute resolution mechanism.

It is also important to remember that the majority of commercial lawyers devote most of their time to transactional matters rather than to disputes. The essence of their work is clarifying their client’s commercial objectives in connection with a transaction and translating them into an agreed form of contract. Part of the lawyer’s role will be to ensure that, so far as is possible, adequate safeguards are built into the contract for their client in the event that things go wrong in the business relationship at a later stage. The lawyer’s objective will be to ensure that, if such difficulties do arise, their client will have a sufficient armoury of legal arguments and remedies to enable them to deal with difficulties in a commercially sensible way. It is in this context that students need to appreciate the necessary overlap between prudent commercial planning by the lawyer and client and a proper appreciation of legal remedies.

It is only by understanding the legal nature of breach and the available legal remedies that parties can make express provision in their contract for particular situations that may arise and so avoid, or at least limit, the potential for full-scale litigation. It should be clear from earlier chapters that lawyers go beyond just specifying what constitutes performance in a contract. They also have to plan for changes in circumstance which might make performance difficult and to plan how disputes which arise should be managed.

CONTRACTUAL PLANNING

A well-structured contract will have addressed these issues at a number of levels. Firstly, the drafter may have been able to anticipate the possibility of particular circumstances arising and may have included a specific remedy or mechanism for addressing the problem. One obvious example of this is a ‘cure notice’ procedure by which the party not in default delivers to the defaulting party a notice specifying the particular breaches complained of and requiring the defaulting party to remedy those breaches within a specified period. As we mention later in this chapter, it is also open to the parties to agree and include in the contract a specified financial penalty in the event of a particular breach occurring. Secondly, where the contract provides no clear answer to the particular breach of which complaint is made, it may contain an escalation procedure by which the parties are required to adopt a number of dispute resolution procedures aimed at securing a speedy settlement of the dispute at modest cost. We deal with such procedures in the next chapter. The final layers of planning are the contractual provisions concerned with exclusion and limitation of liability, liquidated damages and termination procedures.

Empirical studies of the use of contract in the commercial sphere have made clear that the majority of commercial contractors pay little heed to most contractual provisions during the performance of the contract. Case law in preceeding chapters demonstrates that the parties often stray from the original terms and conditions by varying the contract and that they often do so without satisfying the rules relating to consideration. These findings have been used by some to suggest that the formal contract is of little use in the lived world of contract. However, it has also been argued that, whilst this is true during trouble-free performance, the parties will revert to the contractual provisions if a problem arises and they are unable to resolve the problems by using self-help remedies such as re-negotiation of price or time scales. In such circumstances, it is the raft of contractual provisions outlined above and an understanding of the legal remedies available that will provide the foundations for a party’s negotiating stance. For this reason, it is essential for both client and adviser to understand how the courts approach the issue of remedies.

Whilst commercial factors often take precedent over legal doctrine and process, it is clear that, when negotiating a settlement after breach, the parties commonly ‘bargain in the shadow’ of the law. Disputants can and do use the ‘bargaining chips’ created by contractual terms and legal precedent to bolster their position and add credibility to a claim that their position would be upheld by a court. The threat of litigation when used judiciously is, of itself, a powerful tool in the portfolio of the lawyer. Likewise, a proper understanding of the weaknesses in a party’s position can inform that party’s risk and cost analysis and thus perhaps facilitate an early settlement on commercially realistic terms. Whether or not litigation is used, it is important to know what remedies might be available.

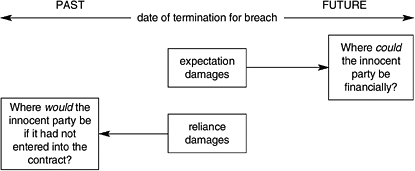

There are three principal remedies for a breach of contract. These are specific performance, termination and damages. It will be seen that each of these respond to different needs. In some circumstances, what the injured party will want most is to bring the contractual relationship to an end as quickly as possible and move on. This is a particularly attractive option where there has been a complete breakdown in trust or it makes better business sense to find another supplier or purchaser. In other cases the injured party might want to insist on performance of contractual obligations. This situation might arise where the party in breach is a specialist, is supplying a rare commodity or has agreed to perform a service at a low cost. In each of these examples termination is not appropriate because the contract is special in some way and cannot easily be replicated. In a third scenario the injured party may need to be compensated for financial losses which have been suffered as a result of the breach. In the remainder of this chapter, we will go on to consider how the three principal remedies available for breach of contract address these various needs.

SPECIFIC PERFORMANCE

When the court issues an order for specific performance, it directs one of the parties to perform its obligations as specified in the contract. Such a remedy may appear to be a very natural one in response to breach of an obligation freely entered into by the party in breach. However, in English law, the remedy of specific performance is rarely granted. This is because it is generally unrealistic to speak of compelling performance in cases where one party is refusing to perform, has so managed their affairs as to make performance out of the question, or has broken the contract in a serious way. As a result, specific performance tends to be granted only where it is realistic to do so and damages are considered to be an inadequate remedy. For example, the remedy will not be granted for contracts for the sale of goods which are readily available elsewhere in the market, but it will be granted where the contractual subject matter is land, property, or other things which fall within the concept of ‘commercial uniqueness’.

In Perry & Co v British Railways Board (1980), Perry obtained an order during the steel strike of 1980, that the Railways Board deliver a quantity of steel owned by him under contract. At the time of the case, steel was very difficult to obtain. Frightened of strike action, the Railways Board had refused to allow it to be moved. In this case it was said that damages would be an inadequate remedy because they would be ‘a poor consolation if the failure of supplies forces a trader to lay off staff and disappoint his customers’. Similarly, the decision in Sky Petroleum Ltd v VIP Petroleum Ltd (1974) was made at a time when there was a petrol shortage. As a result Sky, who had contracted to take all their petrol from VIP, was granted an interim injunction to stop VIP withholding supplies. This amounted to temporary specific performance of a contract for the sale of goods. Although there were normally alternative sources of supply, this was not the case at the time as the market had failed.

Traditionally, the courts have also refused to enforce a contract under which one party is bound by continuous duties. This is because the performance of such contracts might require constant supervision by the court. However, in some such cases specific performance has been ordered and it has been suggested that the difficulty of supervision is sometimes exaggerated. There are various devices that the court can adopt to overcome such difficulty, such as appointing a receiver and manager, Moreover, there are several judicial statements in recent cases to suggest that ‘constant supervision’ is no longer a bar to specific performance but merely a factor to be taken into account. There has also been some indication of an increased willingness by the courts to sanction the use of this remedy, although some doubt has been cast on this change in attitude by the case of Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd (1998). However, the decision of the House of Lords in that case has itself been subject to criticism. As things stand, it would seem that the standard question ‘are damages an adequate remedy?’ might be rewritten to allow for consideration of whether it is just, in all the circumstances, that a claimant should be confined to a remedy in damages?

TERMINATION OF THE CONTRACT

Depending upon the nature of the contractual term breached and the consequences of the breach, the innocent party may be entitled to terminate the contract. This can be done in addition to a claim for damages. The right to do so may be contained in a contractual term or as a matter of general law. The right to terminate a contract is carefully regulated. The judiciary have shown themselves concerned to ensure that the ‘engines of industry’ are slowed as little as possible by breach situations. As a result, it has traditionally given weight to a requirement that the injured party could only terminate a contract following a serious breach and, if it did so, it had a duty to mitigate its loss.

Termination is not a straightforward remedy and must be undertaken with great care if the situation is not to be made even worse. As a first step, the innocent party and their lawyer will need to check the contract carefully to see if it contains express provision for early termination in the event of a breach. Such provisions may restrict or impose conditions upon the right to terminate or may provide a contractual procedure for termination that will need to be implemented in tandem with other rights. If a contractual provision for termination appears to be the safest route, there may be procedures such as service of a cure notice that will need to be followed to make the termination effective. A failure to do so may expose the innocent party to an argument by the defaulting party that the termination is ineffective.

Even an apparently clear provision in a contract giving a right to terminate may not be all it seems. In Rice v Great Yarmouth Borough Council (2000), a council sought to exercise a right of termination by reason of a contractor’s various breaches of a contract for the provision of leisure management and grounds maintenance services. The right of termination for breach was expressed in the following very wide terms: ‘… if the contractor… commits a breach of any of its obligations under the contract… the council may… terminate the contractor’s employment under the contract by notice in writing having immediate effect’. However, the Court of Appeal found that only a repudiatory breach or an accumulation of breaches that as a whole could properly be described as repudiatory could justify termination. In the Court of Appeal, Hale LJJ described the circumstances in which repudiatory breach could be found by the courts and in doing so reminded us that the courts do not easily set aside contracts:

As the judge indicated, there are in effect three catefories: (1) those cases in which the parties have agreed either that the term is so important that any breach will justify termination or that the particular breach is so important that it will justify termination; (2) those contractors who simply walk away from their obligations thus clearly indicating an intention no longer to be bound; and (3) those cases in which the cumulative effect of the breaches which have taken place is sufficiently serious to justify the innocent party in bringing the contract to a premature end…. It is clear that the test of what is sufficiently serious to bring the case within the third of these categories is severe. (paras 35–36)

The court expressed concern that the council appeared to visit the same draconian consequences upon any breach, however small, so long as it was a technical breach of the contract. The court found that the breaches relied upon by the council were found to be insufficiently serious on either an individual or cumulative basis and, as a result, would not allow termination. The breaches did not substantially deny the council the benefit of the contract.

It is also clear that the parties should communicate their concerns to each other prior to a notice to terminate being issued. This was the position in Anglo Group Plc v Winther Browne, & Co Limited (2000) in which Winther Browne, by means of a third-party leasing agreement, purchased a computer system from a supplier. Winther Browne defaulted on payments due and the leasing company sued claiming that Winther Browne had repudiated the contract. Winther Browne claimed that there were defects in the system and counterclaimed for loss of profits and wasted salaries. The court found that contracts for the design and installation of computer systems required parties actively to co-operate with each other. Implied into the contract between Winther Browne and the supplier was a term requiring Winther Browne to communicate its needs clearly to the supplier and that the parties work together to resolve problems. The defects in the system had not been proven to constitute fundamental breaches of contract entitling Winther Browne to repudiate the contract. The suppler had performed substantially what it had contracted to do and Winther Browne had not fully co-operated in helping to resolve problems that had arisen.

A decision to terminate has to be properly communicated to the party in breach. The right to terminate may be lost if, in the meantime, the innocent party demonstrates an intention to continue with the contract. This might be the case, for example, if they place an order for additional services or make an advance payment of charges due under the contract. If the innocent party gets it wrong and purports to terminate in circumstances where, as a matter of law, it was not entitled to do so, the party in breach may be able to treat such ‘wrongful’ termination as a basis upon which it can then legitimately terminate the contract.

Where an ineffective termination by the innocent party enables the defaulting party to terminate, the end result (termination of the contract) is clearly the same. However, there may be very serious financial consequences for the innocent party. If the party in breach is struggling to meet its obligations or can only do so on an uneconomic basis, it may like nothing better than for the innocent party to terminate in circumstances where it may not have been entitled to do so. Not only will the defaulting party have escaped future performance under the contract but it may also have a claim against the innocent party for damages for wrongful termination. Even the opportunity for the defaulting party to raise such an argument will enhance its position in any subsequent negotiations for settlement that may take place.