WINDING UP AND DISSOLUTION OF A COMPANY

Winding up and dissolution of a company

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Identify the different types of winding up

Identify the different types of winding up

Decide whether a document creates a fixed or floating charge Determine the order of priority of charges against the same property

Decide whether a document creates a fixed or floating charge Determine the order of priority of charges against the same property

Appreciate the importance of registration of charges

Appreciate the importance of registration of charges

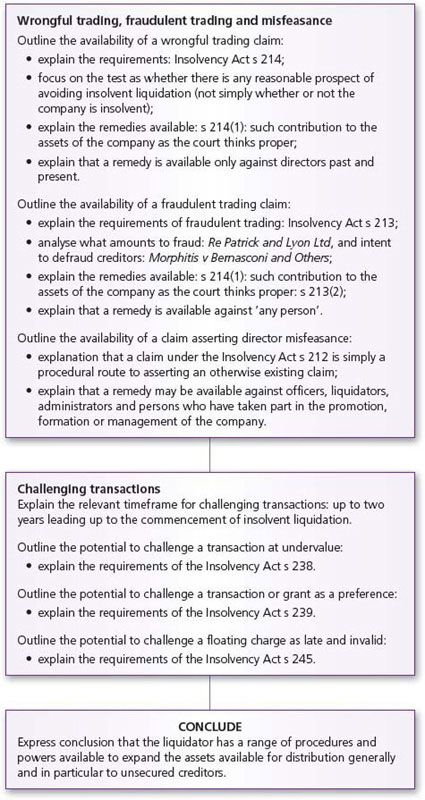

Advise on the steps a liquidator may take to avoid certain pre-winding up transactions

Advise on the steps a liquidator may take to avoid certain pre-winding up transactions

Advise on the steps a liquidator may take to swell the asset pot available for distribution

Advise on the steps a liquidator may take to swell the asset pot available for distribution

Advise on the statutory order of distribution of the assets of a company on a winding up

Advise on the statutory order of distribution of the assets of a company on a winding up

Appreciate the routes available to dissolution of a company

Appreciate the routes available to dissolution of a company

liquidation

The winding up of a company

Before a company ceases to exist, its affairs should be wound up. ‘Winding up’ and ‘liquidation’ mean the same thing. Essentially, in a winding up, any assets the company has are sold to turn them into cash which is distributed to meet the company’s liabilities. The name of the company is then removed by the registrar from the register of companies and at that point the company ceases to exist. Most companies cease to exist without being formally wound up. If a company ceases to trade, has no assets and stops making the required annual returns to the registrar, for example, the registrar may remove its name from the register of companies (see the final section of this chapter).

When a solvent company is wound up, all creditors are paid in full and the surplus is shared between the shareholders in accordance with their class rights. As noted in Chapter 7, the shareholders may decide to wind up a company and share out its residual wealth by passing a special resolution.

The situation is very different if a company is insolvent. The board of a company finding itself in financial trouble, struggling to pay its debts, including interest payments on its loans, will try to renegotiate the terms of loans and other credit arrangements to reach a voluntary compromise or settlement or composition (a range of terms are used) with its creditors to give the company a breathing space to trade itself back into financial good health.

In addition to informal efforts, three statutory legal processes are available to a company in financial difficulties to try to avoid the need to liquidate and dissolve the company: formal company voluntary arrangements, formal small company voluntary arrangements with a moratorium and administration. All three were considered in Chapter 15.

If efforts to renegotiate legal agreements with its creditors are unsuccessful, and the mechanisms in Chapter 15 are unsuccessful, a company is likely to enter liquidation or, put another way, be wound up. In this chapter we focus on companies entering into insolvent winding up. We briefly consider the different types of winding up (solvent and insolvent), followed by an examination of the most common forms of loan security: fixed and floating charges. An understanding of the basic types of loan security is important to understand the order in which the liquidator shares out the assets of a company amongst its creditors. We then look at the assets available for distribution in a winding up, the steps liquidators may take to avoid certain pre-winding up transactions and swell the asset pot available for distribution, and the statutory order of distribution of assets. Finally, we identify nine routes to dissolution of a company.

Unless indicated otherwise, statutory references in this chapter are to sections of the Insolvency Act 1986.

voluntary winding up

The winding up of a company commenced by a special resolution of its members

statutory declaration of solvency

A statement made by the board for the purposes of s 89 of the Insolvency Act 1986 which confirms that the directors have formed the opinion, based on reasonable grounds, that the company will be able to pay its debts in full within a period not exceeding 12 months from the commencement of the voluntary winding up

A company may be wound up whether it is solvent or insolvent. Two types of winding up exist: voluntary winding up and compulsory winding up.

A voluntary winding up is commenced by the passing of a special resolution by the shareholders (Insolvency Act 1986, s 84(1)(b)). A voluntary winding up will be:

a members’ voluntary winding up, if a statutory declaration of solvency (that they are of the opinion that the company will be able to pay its debts in full within a specified time of no more than 12 months) has been made by the directors in accordance with s 89; or

a members’ voluntary winding up, if a statutory declaration of solvency (that they are of the opinion that the company will be able to pay its debts in full within a specified time of no more than 12 months) has been made by the directors in accordance with s 89; or

a creditors’ voluntary winding up, if no such statutory declaration has been made (s 90), or, if a declaration of solvency has been made but, subsequently, the liquidator disagrees with the declaration and is of the opinion that the company will be unable to pay its debts in full within the specified period (s 96).

a creditors’ voluntary winding up, if no such statutory declaration has been made (s 90), or, if a declaration of solvency has been made but, subsequently, the liquidator disagrees with the declaration and is of the opinion that the company will be unable to pay its debts in full within the specified period (s 96).

compulsory liquidation or compulsory winding up

The winding up of a company by order of the court

A compulsory winding up is commenced by presentation of a petition to the court followed by an order of the court (Insolvency Act 1986, ss 122 and 124). The winding up is deemed to have commenced at the time of presentation of the petition, i.e. earlier than the date of the order (s 129(2)). The principal grounds on which a company may be wound up by the court are:

the company is unable to pay its debts (s 122(1)(f));

the company is unable to pay its debts (s 122(1)(f));

the court is of the opinion that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up (s 122(1)(g) (see Chapter 14)).

the court is of the opinion that it is just and equitable that the company should be wound up (s 122(1)(g) (see Chapter 14)).

Creditors typically present a petition seeking a winding up on the first ground whereas minority shareholders typically seek a winding up on the second ground (see section 14.6.1).

The focus of this chapter is insolvent winding up, which can be either voluntary or compulsory. A company is insolvent when it is unable to pay its debts. In these circumstances either the company itself passes a special resolution to commence a creditors’ voluntary winding up or a winding-up petition is presented to the court, most commonly by a creditor who is owed £750 or more and has served an unpaid statutory demand on the company (s 123(1)(a)), or a creditor who has secured a judgment for any sum owed to him and execution of that judgment has failed (s 123(1)(b)).

16.2.4 Sources of insolvency law

The main statute governing windings up is the Insolvency Act 1986, as amended, most significantly for our purposes, by the Enterprise Act 2002. The main regulations are the Insolvency Rules 1986. The Companies Act 2006 also contains provisions important to winding up and a host of other Acts and statutory instruments are relevant, making the structure of the law unsatisfactory.

QUOTATION

‘It has to be said that the structure of English insolvency legislation does not display a particularly rational structure or scheme of arrangement … Overall the Insolvency Act and the Insolvency Rules have become a legislative morass through which even the experienced practitioner cannot pick his way without difficulty.’

Goode 2005

In an effort to address this state of affairs, the Insolvency Service (an executive agency of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, or BIS) has been working for a number of years on the Modernisation of Insolvency Rules Project, to ‘reduce the regulatory and administrative burdens that exist for users of insolvency legislation’. The final phase of the modernisation, ‘to produce a new set of Insolvency Rules to restructure and entirely replace the 1986 Rules, which have been amended more than 20 times since they came into force’, resulted in the publication in September 2013 of a first draft of the Insolvency Rules 2015. A second draft was yet to be published at the time of updating this text. Progress can be tracked on the website referenced under further reading at the end of this chapter.

winding-up order

A court order to liquidate a company

official receiver

A civil servant in the Insolvency Service (an executive agency of BIS) and an officer of the court. The first liquidator of any company subject to compulsory winding up

16.2.5 Effects of a winding-up order or appointment of a liquidator

Once a winding-up order has been made (in a compulsory winding up), or a liquidator has been put in place (in a creditors’ voluntary winding up), the powers of the board of directors cease. No person may commence or continue any legal actions against the company or its property without the leave of the court (s 130(2)) and control of the assets of the company passes to the liquidator.

In a compulsory winding up, the initial liquidator is the official receiver. The liquidator exercises statutory powers as an agent for the company (Knowles v Scott [1891] 1 Ch 717). His role is returned to in section 16.4 after we have examined loan security and, in particular, fixed and floating charges.

When a company enters insolvent winding up the liquidator is required to draw up a list of creditors of the company whose claims that the company owes them money have come up to proof. Creditors fall into categories: preferential creditors, secured creditors, unsecured creditors and deferred creditors. Secured creditors are those who, in addition to having a contractual right to sue the company for the return of any money owed to them, have taken a property interest in one or more items of the company’s property as security for the credit they have made available to the company.

The existence of a property interest, or a ‘charge’, ordinarily permits the holder of that interest to take possession of the asset in certain circumstances and thereby remove it from the pot of assets available to the liquidator to liquidate and distribute rateably amongst those creditors who have only contractual rights against the company (unsecured creditors). In this way, the property interest, the security, reduces the risk to the secured creditor of not getting its money back. By reducing risk, security facilitates the lending of money (see Re Brightlife Ltd [1987] Ch 200, at section 16.3.3). As we shall see, not all of those with a property interest have the right to take possession of the charged property. Floating chargeholders, for example, do not have the right to take possession of the charged property (although their rights are greater than those of unsecured creditors).

16.3.1 Classification of loan security

Loan securities can be classified according to a number of criteria. Three classification criteria are commented on in this section.

charge

A legal or equitable property interest in some or all of the assets of the company created to secure a loan to the company or to secure some other right against the company

Mortgages and charges

Although a distinction is often made in property law between a mortgage and a charge, this distinction is not usually important in company law. The term ‘charge’ is regularly used to describe a loan security whether the security established is a charge or a mortgage. For the purposes of registration of charges, for example, s 859A(7) states that charge includes a mortgage. For the purposes of the insolvency process, s 248 of the Insolvency Act 1986 defines secured creditor as a creditor who holds security over property of the company in respect of his debts, which it defines to include both charges and mortgages. No attempt is made in this chapter to distinguish security operating by way of mortgage from security operating by way of charge.

Legal and equitable property interests

Loan security may provide the lender with an equitable interest or legal property right in the charged property. The distinction is particularly important where more than one property interest has been granted in relation to the same item of property. In deciding which property interest takes priority, that is, the order in which secured lenders will be entitled to the proceeds of sale of the property, legal rights almost always take priority over equitable interests. The order of priority will be affected, however, by whether or not the charge has been properly registered with the registrar in accordance with the Companies Act 2006. Priority and registration are dealt with at section 16.3.6.

Fixed and floating charges

When we study winding up we need to understand not only the rights of secured creditors vis-à-vis other creditors but also the rights of different types of secured creditors. In this context it is critically important to classify charges into fixed and floating charges, an important distinction for at least two key reasons.

Second, a floating charge is vulnerable to avoidance pursuant to the Insolvency Act 1986, s 245, whereas a fixed charge is not (see avoidance of transactions at section 16.4.2).

For these reasons, amongst others, it is essential to know how to decide whether a particular security interest is a fixed or floating charge. Also for these reasons, banks go out of their way to characterise charges as fixed charges, seeking to establish the much stronger rights of a fixed chargeholder in the event of a winding up, when, in reality, the charge in question has operated as a floating charge. The distinction between fixed and floating charges was introduced in Chapter 6 where we considered debt financing and you may find it useful to reread the secured funding part of that chapter (section 6.4.6) before reading on.

A fixed charge, also sometimes called a specific charge, is a property interest in specific property preventing the owner of the property from selling the property or otherwise dealing with it without first either:

paying back the sum secured against it; or

paying back the sum secured against it; or

securing the consent of the chargeholder.

securing the consent of the chargeholder.

A fixed charge is created by a deed or other charge document (called a debenture), usually at the same time the loan is made or a credit facility (such as an overdraft facility) is put in place. The rights of the fixed chargeholder will be determined by the language of the charge document which stipulates what the chargeholder may do in relation to the charged property and in which eventualities. Typically, the fixed chargeholder has the right to take possession of the charged property, sell it and recover from the proceeds of sale the secured sum and costs reasonably incurred. Any surplus proceeds are returned to the company. Additionally, or alternatively, the charge will empower the chargeholder to appoint a receiver to take possession of the property on its behalf. The chargeholder is empowered to take these steps only if and when certain events occur, such as the company defaulting on payment of one or more repayments, or the company entering into liquidation. Figures 6.1 and 6.2 in Chapter 6 illustrate how fixed charges work.

receiver

A person appointed under a debenture or other instrument secured over the assets of a company to manage and realise the secured assets for the benefit of the chargeholder

No simple legal definition of a fixed charge exists. It is a non-possessory security that is not a floating charge. Non-possessory means that the person who benefits from the charge does not have possession of the charged property. Possession remains with the company. This is the reason why it is important to have a public register of charges so that third parties, by consulting the register, are able to discover whether or not a piece of property owned and in the possession of the company is subject to any of the registrable charges. The essence of a fixed charge is that control over dealing with the charged property rests with the bank/lender/creditor/chargee/chargeholder. In contrast, property subject to a floating charge may be dealt with (usually sold) by the company in the ordinary course of business without seeking the consent of the chargee.

The meaning of fixed charge has been explored in several significant cases in the past 20 years in which liquidators and the Inland Revenue (now HM Revenue & Customs) have sought to challenge charges described on their face as fixed charges, arguing that they are, in reality, floating charges. In Re Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] 2 AC 680 (HL), Lord Scott emphasised that it is the substance of the rights created and not the form that determines the nature of the charge.

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘[T]he label of “fixed” or “specific” (which I take to be synonymous in this context) cannot be decisive if the rights created by the debenture, properly construed, are inconsistent with that label.’ | |

Before the relevant sections of the Enterprise Act 2002 came into effect, unpaid taxes of a company that went into winding up were payable as preferential debts. This is no longer the case, but it was the case when the facts of the four major cases exploring the line between fixed and floating charges arose. Accordingly, the taxing authorities were keen to establish that the form of security scrutinised in the cases were floating charges thereby requiring the liquidator to pay the unpaid taxes out of the proceeds of sale of the charged assets before applying any of those proceeds to pay back the chargeholder.

The four leading cases in which a charge named on its face as a fixed charge was examined to determine what rights the parties intended to create and whether or not, as a matter of law, those rights constituted a fixed or a floating charge are:

Siebe Gorman & Co Ltd v Barclays Bank Ltd [1979] 2 Lloyds Rep 142 (overruled in Re Spectrum);

Siebe Gorman & Co Ltd v Barclays Bank Ltd [1979] 2 Lloyds Rep 142 (overruled in Re Spectrum);

Re New Bullas Trading Ltd [1994] 1 BCLC 485 (PC) (overruled in Agnew);

Re New Bullas Trading Ltd [1994] 1 BCLC 485 (PC) (overruled in Agnew);

Agnew v Commissioner of Inland Revenue (Re Brumark Investments Ltd) [2001] 2 AC 710 (PC) (approved in Re Spectrum);

Agnew v Commissioner of Inland Revenue (Re Brumark Investments Ltd) [2001] 2 AC 710 (PC) (approved in Re Spectrum);

Re Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] 2 AC 680 (HL).

Re Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] 2 AC 680 (HL).

The leading authority, Re Spectrum, a test case on a widely used standard form of debenture, is discussed at section 16.3.4 when we examine charges over book debts.

Justice Hoffmann (as he then was) explained the role played by floating charges in Re Brightlife Ltd [1987] Ch 200. He highlighted the tension between the rights of floating chargeholders and unsecured creditors, stating that responsibility for balancing these competing interests lies with the legislature, not the courts.

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘The floating charge was invented by Victorian lawyers to enable manufacturing and trading companies to raise loan capital on debentures. It could offer the security of a charge over the whole of the company’s undertaking without inhibiting its ability to trade. But the mirror image of these advantages was the potential prejudice to the general body of creditors, who might know nothing of the floating charge but find that all the company’s assets, including the very goods which they had just delivered on credit, had been swept up by the debenture holder. The public interest requires a balancing of the advantages to the economy of facilitating the borrowing of money against the possibility of injustice to unsecured creditors. These arguments for and against the floating charge are matters for Parliament rather than the courts and have been the subject of public debate in and out of Parliament for more than a century. Parliament has responded, first, by restricting the right of the holder of a floating charge and secondly, by requiring public notice of the existence and enforcement of the charge.’ | |

a charge upon all of a certain class of assets present and future;

a charge upon all of a certain class of assets present and future;

which class is, in the ordinary course of the company’s business, changing from time to time;

which class is, in the ordinary course of the company’s business, changing from time to time;

in relation to which charged assets, until steps are taken to enforce the charge, the company can carry on business in the ordinary way including removing a charged asset from the security.

in relation to which charged assets, until steps are taken to enforce the charge, the company can carry on business in the ordinary way including removing a charged asset from the security.

In Agnew v Commissioner of Inland Revenue (Re Brumark Investments Ltd) [2001] 2 AC 710 (PC) Lord Millett stressed it is the third of these characteristics that is the essential feature of a floating charge and which distinguishes a floating charge from a fixed charge. A fixed charge may have one or both of the first characteristics listed above but may not have the third.

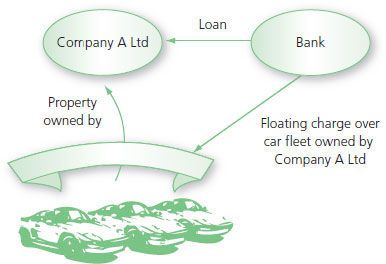

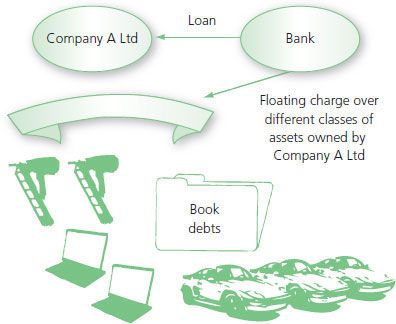

Figures 16.1 and 16.2 illustrate how a floating charge may be put in place over a single class of assets or a number of different classes of assets. It is common for floating charges to be put in place over ‘all the assets and business of the company’. This is referred to as a general floating charge. The great attraction and benefit of a floating charge is that the company can continue to use the charged assets of the company, buying and selling them in the ordinary course of business, without recourse to the chargeholder, until, that is, the charge crystallises. Until crystallisation, the property interest of the chargee simply floats above the assets, hence the name ‘floating charge’.

crystallisation

On crystallisation, a floating charge becomes a fixed charge

Crystallisation of a floating charge

The effect of crystallisation

On crystallisation, a floating charge becomes a fixed charge. The right of the company to deal with the charged assets in the ordinary course of business ceases and the rights of the chargeholder/bank are essentially those stated for a fixed chargeholder above, except that if the company is being wound up those rights are subject to the Insolvency Act 1986 provisions overriding them.

Also, do not think that because a floating charge becomes a fixed charge at the point of crystallisation it is thereby taken outside the statutory insolvency law provisions applicable to floating charges. Although it is possible to provide in a floating charge that it will crystallise in circumstances that occur before the commencement of a winding up, Parliament has acted to neutralise the effect of such provisions by providing in the Insolvency Act 1986 that for the purposes of a winding up, ‘floating charge’ is defined as, ‘a charge which, as created, was a floating charge’ (s 251) (emphasis added). Consequently, provided the charge started its life as a floating charge, it is treated as a floating charge in a winding up.

Figure 16.1 Floating charge over single class of assets.

Figure 16.2 Floating charge over different classes of assets.

When does crystallisation occur?

Crystallisation of a floating charge occurs on/when:

appointment of a receiver;

appointment of a receiver;

the company goes into liquidation;

the company goes into liquidation;

the company ceases to carry on business/sells its business;

the company ceases to carry on business/sells its business;

a notice of conversion being given (if the charge document gives the chargeholder/bank the right to convert the charge from floating to fixed on giving notice);

a notice of conversion being given (if the charge document gives the chargeholder/bank the right to convert the charge from floating to fixed on giving notice);

an event occurs which, under the terms of the charge document, causes ‘automatic crystallisation’.

an event occurs which, under the terms of the charge document, causes ‘automatic crystallisation’.

The freedom of the parties to stipulate the crystallisation events was supported by Hoffmann J in Re Brightlife Ltd [1987] Ch 200 subject to statutory provisions that cannot be contracted out of.

book debt

A debt arising in the course of a business that would or could in the ordinary course of business be entered in well-kept books of account of the business

16.3.4 Charges over book debts

What is a book debt?

Sums receivable, either immediately or at some date in the future, by a company operating a business (‘receivables’) are important assets of a company. When they are used to raise capital for the company it is called ‘receivable financing’. Book debts are a very important type of receivable. They can be either sold (assigned) to raise capital for the company (the sale price), or charged as security for a loan made to the company.

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘Shipley v Marshall [(1863) 14 CBNS 566], I think, establishes that, if it can be said of a debt arising in the course of a business and due or growing due to the proprietor of that business that such a debt would or could in the ordinary course of such a business be entered in well kept books relating to that business, that debt can properly be called a book debt whether it is in fact entered in the books of the business or not.’ | |

Book debts example

Company A Ltd manufactures shoes and sells them to wholesaler customers. The customers to whom it sells shoes in December 2013 are B, C, D, E and F. The customers it sells to in January 2014 are D, E, F, G and H. The terms of supply provide for the price to be paid within 45 days of invoice. The sums owed to Company A Ltd are recorded in its books of account as assets. These assets are called ‘book debts’ and they are choses in action. When the debtor pays the invoiced sum, the book debt is extinguished and the cash payment is deposited in the bank account of Company A Ltd. If a debtor/customer does not pay the sum due by the due date the Company can sue the debtor to recover the debt. Company A Ltd’s list of book debts is constantly changing. The following table illustrates this:

Book debts of Company A Ltd | |

1 January 2014 | 1 February 2014 |

B owes £10,000 | D owes £15,000 |

C owes £5,000 | E owes £1,000 |

D owes £1,000 | F owes £1,000 |

E owes £1,000 | G owes £6,000 |

F owes £1,000 | H owes £9,000 |

In January 2014, wholesaler B pays the invoice for the shoes it has bought from Company A Ltd in December 2013 by sending Company A Ltd a cheque for £10,000. The book debt owed by wholesaler B ceases to exist and does not appear in the list of book debts of Company A Ltd on 1 February 2014. Company A Ltd has, in its place, a cheque. Company A Ltd deposits the cheque in its bank account. Company A Ltd uses the money in the bank account in the ordinary course of running the business, to pay bills, employee wages, taxes, etc.

Fixed charges over book debts

Charges over book debts are usually floating charges. It is theoretically possible to have a fixed charge over book debts but the chargeholder/bank must control the property charged.

| Re Spectrum Plus Ltd [2005] 2 AC 680 (HL) A standard form charge used widely by banks to take security over book debts, present and future, of a company, was expressed on its face to be a specific charge, meaning a fixed charge. The Inland Revenue challenged the nature of the charge, seeking to have it declared to be a floating charge so that the proceeds of sale of the book debts in the hands of the liquidator had to be used to pay off preferred debts (which, when the facts of the case arose, included unpaid taxes, although this is no longer the case). The charge provided that the company could not deal with uncollected book debts. It also required the proceeds of the book debts (the sums paid by the book debtors to the company extinguishing the book debt) to be paid into the company’s current account with the bank. Provided the overdraft limit on that account was not exceeded, the company could draw sums freely out of the bank account and use the sums for its business purposes. Held: The document created a floating charge not a fixed charge. The account into which the proceeds of the book debts was to be paid was not a ‘blocked account’, that is, one that the company could not draw on without the consent of the chargee bank and therefore the company was free to deal with the proceeds of the book debts in the ordinary course of its business. This did not give the bank the control over the charged asset that is required to establish a fixed charge. | |

Following Re Spectrum Plus Ltd (2005), the leading case on the defining features of a fixed charge and which involved a charge over book debts, there are three stages to the control needed for a charge over book debts to be a fixed charge:

the company must not be able to sell or use the book debts as security without the consent of the chargeholder/bank (so no using the charged book debts for receivables financing);

the company must not be able to sell or use the book debts as security without the consent of the chargeholder/bank (so no using the charged book debts for receivables financing);

the sum paid to the company by the book debtors must be paid into an account specified by the chargeholder/bank;

the sum paid to the company by the book debtors must be paid into an account specified by the chargeholder/bank;

the proceeds in the bank account must be useable by the company only with the consent of the chargee/bank (it must be a ‘blocked account’): essentially, the chargee/bank must control withdrawals from the bank account into which the book debt receipts are paid, both in theory and in practice.

the proceeds in the bank account must be useable by the company only with the consent of the chargee/bank (it must be a ‘blocked account’): essentially, the chargee/bank must control withdrawals from the bank account into which the book debt receipts are paid, both in theory and in practice.

Note that although not strictly needed for the decision in the case, the court in Re Spectrum did not consider that a court should confine its concern to the language of the documentation creating the charge but should also consider how the charge was operated in practice. Lord Scott, referring to the words of Lord Millet in Agnew v Commissioner of Inland Revenue (Re Brumark Investments Ltd) [2001] 2 AC 710 (PC), said, ‘It was not enough to provide in the debenture for an account to be blocked, if it was not in fact operated as a blocked account.’ Where, therefore, the language of the document gives the chargee bank control over the bank account but as a matter of fact that control is not exercised, the charge will not be a fixed charge.

16.3.5 Registration of charges

The obligation to register, with the registrar of companies, a charge created by a company over some or all of its property, backed by criminal penalties for non-compliance, was removed in 2013 (see the Companies Act 2006 (Amendment of Part 25) Regulations 2013 (SI 2013/600)). Today, although registration with the registrar of companies is technically optional, the civil law consequences for the chargee of failure to do so provide a strong incentive to register. The new Companies Act 2006 registration regime is considered below.

When considering a charge over land granted by a company, in addition to the Companies Act registration regime, it is important to consider whether or not to register the charge at the Land Registry or the Land Charges Department. Even if registration is not required, it is important to consider the benefits to the chargeholder that flow from registering the charge at the Land Registry or the Land Charges Department. Registration and priority of interests in land is complex.

Charges over Land

Registered land charges

If it is to take effect as a legal mortgage, a legal charge over registered land owned by the company must be registered at the Land Registry pursuant to s 27(2)(f) of the Land Registration Act 2002. A number of other charges can also be ‘noted’ on the land register to protect the chargeholder’s position. Registration under the 2002 Act and the effects of registration and non-registration operate in addition to the Companies Act 2006 registration regime.

Unregistered land charges

A charge over unregistered land owned by the company may be registered with the Land Charges Department pursuant to the Land Charges Act 1972 and failure to do so will often result in the charge being void against the purchaser of certain interests in the property (precisely which interests depends upon the type of charge). Again, registration under the 1972 Act and the effects of registration and non-registration operate in addition to the Companies Act 2006 registration regime.

Registration with the registrar of companies (s 859A-Q)

The rules for registering charges created on or after 6 April 2013 with the registrar of companies changed significantly as a result of the Companies Act 2006 (Amendment of Part 25) Regulations 2013 (SI 2013/600), which repealed ss 860–892 of the Companies Act 2006, replacing them with ss 859A–Q. As stated above, the criminal penalty for non-registration no longer exists and, technically, the statutory provisions no longer make registration a legal obligation, but the civil law consequences for the chargeholder of failure to register provide a strong incentive to register. The changes are intended to:

streamline procedures and reduce costs, particularly by enabling electronic filing;

streamline procedures and reduce costs, particularly by enabling electronic filing;

clarify the scope of the registration regime, i.e. which charges need to be registered in order to protect the chargeholder’s rights;

clarify the scope of the registration regime, i.e. which charges need to be registered in order to protect the chargeholder’s rights;

create a single registration scheme for all UK-registered companies (charges are now registered in one place, not with the three registrars depending upon the place of incorporation of the company); and

create a single registration scheme for all UK-registered companies (charges are now registered in one place, not with the three registrars depending upon the place of incorporation of the company); and

expand the information about the charge available to third parties.

expand the information about the charge available to third parties.

Charge is defined in s 859A(7). It includes a mortgage. All charges except those listed in s 859A(6) may be registered. (Charges on cash deposits connected with leases of land and charges made by members of Lloyds are the only two charges listed in s 859A(6) as not registrable but provision is made for specified types of charges to be excepted by provisions in other statutes.)

The documents to be delivered to register a charge are:

a statement of particulars; and

a statement of particulars; and

a certified copy of the document creating the charge (which can be delivered as a pdf) (s 859A).

a certified copy of the document creating the charge (which can be delivered as a pdf) (s 859A).

The contents of the statement of particulars (s 859D) are:

the registered name and number of the company;

the registered name and number of the company;

the date of creation of the charge and (if applicable) the date of acquisition of the property or undertaking concerned;

the date of creation of the charge and (if applicable) the date of acquisition of the property or undertaking concerned;

where the charge is created or evidenced by an instrument:

where the charge is created or evidenced by an instrument:

the name of each of the persons in whose favour the charge has been created;

the name of each of the persons in whose favour the charge has been created;

whether the instrument is expressed to contain a floating charge and, if so, whether it is expressed to cover all the property and undertaking of the company;

whether the instrument is expressed to contain a floating charge and, if so, whether it is expressed to cover all the property and undertaking of the company;

whether any of the terms of the charge prohibit or restrict the company from creating further security that will rank equally with or ahead of the charge (i.e. a negative pledge clause);

whether any of the terms of the charge prohibit or restrict the company from creating further security that will rank equally with or ahead of the charge (i.e. a negative pledge clause);

whether (and if so, a short description of) any land, ship, aircraft or intellectual property that is registered or required to be registered in the United Kingdom, is subject to a charge (which is not a floating charge) or fixed security included in the instrument;

whether (and if so, a short description of) any land, ship, aircraft or intellectual property that is registered or required to be registered in the United Kingdom, is subject to a charge (which is not a floating charge) or fixed security included in the instrument;

whether the instrument includes a charge (which is not a floating charge) or fixed security over any tangible or corporeal property, or any intangible or incorporeal property, not described in the foregoing bullet point; and

whether the instrument includes a charge (which is not a floating charge) or fixed security over any tangible or corporeal property, or any intangible or incorporeal property, not described in the foregoing bullet point; and

where the charge is not created or evidenced by an instrument:

where the charge is not created or evidenced by an instrument:

a statement that there is no instrument creating or evidencing the charge;

a statement that there is no instrument creating or evidencing the charge;

the names of each of the persons in whose favour the charge has been created;

the names of each of the persons in whose favour the charge has been created;

the nature of the charge;

the nature of the charge;

a short description of the property or undertaking charged; and

a short description of the property or undertaking charged; and

the obligations secured by the charge.

the obligations secured by the charge.

A charge may be registered within 21 days beginning with the day after the date of creation of the charge, or any extended period ordered by the court under s 859F(3). If a company acquires property subject to a charge, however, no time limit is specified within which that charge may be registered to preserve its enforceability.

On registration of a charge, the registrar of companies gives a certificate of registration which is conclusive evidence that the requirements of the Act as to registration have been complied with (s 859I(6)). The decision to issue a certificate is not subject to judicial review (R v Registrar of Companies, ex parte Central Bank of India [1986] QB 1114).

If a charge is not registered in the time provided the court may extend the time to register the charge. Under the old rules, late registration was only granted subject to the standard proviso, known as the ‘Joplin’ proviso, that registration was without prejudice to the rights of parties acquired during the period between the date by which the charge should have been registered and the date of its actual registration (Re Joplin Brewery Co Ltd [1902] 1 Ch 79). It was also settled practice that a court would not make an order under extending time for registration if the application was made after winding up of the company has commenced, and there is no reason to expect these practices to change.

Failure to register a charge within the initial or extended time period renders the charge void (so far as any security on the company’s property or undertaking is conferred by it) against a liquidator, administrator or creditor of the company (S 859h(3)). Even if a second chargeholder knew of the creation of the prior unregistered charge, the prior charge is still void against the second chargeholder (Re Monolithic Building Co [1915] Ch 643). The obligation to repay the money secured by the charge continues (i.e. the loan secured by the charge is not void) and, by s 859H(4), the money secured becomes repayable immediately.

Note that when the company is a going concern in good financial health, (i.e. is not in administration or being wound up), even an unregistered charge is valid and can be enforced against the company. The importance of registration when a company is a going concern is to establish priority over other secured creditors; subsequent registered charges will take priority over an unregistered charge. Smith (Administrator of Coslett (Contractors) Ltd) v Bridgend County Borough Council [2001] 1 All ER 292 decided that, in the event of insolvency, an unregistered registrable charge is void against a company. In effect, on a winding up, the creditor becomes an unsecured creditor.

When a registered charge is released, or property subject to the registered charge has ceased to form part of the company’s property, or the debt for which the registered charge was given has been paid (in whole or in part), the company sends the information required by s 859L to the registrar who will enter a statement of satisfaction or release, as the case may be, on the register.

Registration in the company’s own register

The obligation imposed upon a company to maintain a register of charges was also removed in 2013 by the repeal of s 876 by the Companies Act 2006 (Amendment of Part 25) Regulations 2013 (SI 2013/600).

Copies and inspection of charge documentation

Sections 859P and 859Q require a company to keep a copy of every instrument creating or amending a charge available for inspection at its registered office. This copy can be in the same form as that delivered to the registrar (i.e. may be subject to redactions). It must be open to the inspection of any creditor or shareholder without charge and to any other person subject to payment of a prescribed fee. Failure to make the instrument available within 14 days of a request is punishable by a fine which can be imposed on the company and any officer of the company who is in default.

Provided charges have been properly registered with the registrar pursuant to s 859A, the following basic rules apply to determine the priority of charges:

Fixed charges rank in order of the time at which they are created: the first in time takes priority over all subsequent fixed charges over the same property.

Fixed charges rank in order of the time at which they are created: the first in time takes priority over all subsequent fixed charges over the same property.

Fixed charges establish stronger rights than floating charges and a later-in-time fixed charge ranks in priority over an earlier floating charge (Re Castell & Brown Ltd [1898] 1 Ch 315). Except that if the subsequent fixed chargeholder had actual or constructive knowledge, at the time its charge was entered into, that the pre-existing floating charge expressly prohibited the company from creating a subsequent charge with priority, the pre-existing floating charge will take priority over the subsequent fixed charge (Siebe Gorman & Co Ltd v Barclays Bank Ltd [1979] 2 Lloyds Rep 142, which remains good law on this point). Such a clause is known as a ‘negative pledge’. A negative pledge principally operates as a contractual right between the company and the first chargeholder. Note that prior to 6 April 2013, registration with the registrar of the pre-existing floating charge was not enough to confer constructive knowledge on a subsequent fixed charge-holder to stop the subsequent fixed charge from taking priority as the registration system did not require the existence of a negative pledge to be registered. Note that the new rules do not expressly clarify the vexed question of how the doctrine of constructive notice operates in relation to the registration of charges, and, in particular, the effect of a negative charge clause in a registered charge. This is because to provide clarification on this issue was characterised as potentially interfering with property rights which is beyond the powers of amendment conferred on the Secretary of State by ss 894(1) and 1292(1) of the Companies Act 2006. Briefly, the position appears to be that if, at the time a fixed charge is granted by a company, the person to whom it is granted has either actual or constructive knowledge of a negative pledge in an existing, properly registered floating charge, the floating charge takes priority over the later fixed charge. For a charge registered on or after 6 April 2013, as it is part of the statement of particulars (see above), whether or not the charge contains a negative pledge will be clear from the register. Accordingly, any person checking the register will have actual knowledge of the negative pledge and their charge will not take priority over the floating charge containing the negative pledge. The assertion that a later fixed chargeholder who does not check the register will be held to have constructive notice of a negative pledge, in an earlier, registered floating charge, is not wholly without doubt but it is very likely that constructive notice will be found to exist. Accordingly, it is very likely that a floating charge containing a negative pledge registered on or after 6 April 2013 will take priority over a subsequently granted fixed charge.

Fixed charges establish stronger rights than floating charges and a later-in-time fixed charge ranks in priority over an earlier floating charge (Re Castell & Brown Ltd [1898] 1 Ch 315). Except that if the subsequent fixed chargeholder had actual or constructive knowledge, at the time its charge was entered into, that the pre-existing floating charge expressly prohibited the company from creating a subsequent charge with priority, the pre-existing floating charge will take priority over the subsequent fixed charge (Siebe Gorman & Co Ltd v Barclays Bank Ltd [1979] 2 Lloyds Rep 142, which remains good law on this point). Such a clause is known as a ‘negative pledge’. A negative pledge principally operates as a contractual right between the company and the first chargeholder. Note that prior to 6 April 2013, registration with the registrar of the pre-existing floating charge was not enough to confer constructive knowledge on a subsequent fixed charge-holder to stop the subsequent fixed charge from taking priority as the registration system did not require the existence of a negative pledge to be registered. Note that the new rules do not expressly clarify the vexed question of how the doctrine of constructive notice operates in relation to the registration of charges, and, in particular, the effect of a negative charge clause in a registered charge. This is because to provide clarification on this issue was characterised as potentially interfering with property rights which is beyond the powers of amendment conferred on the Secretary of State by ss 894(1) and 1292(1) of the Companies Act 2006. Briefly, the position appears to be that if, at the time a fixed charge is granted by a company, the person to whom it is granted has either actual or constructive knowledge of a negative pledge in an existing, properly registered floating charge, the floating charge takes priority over the later fixed charge. For a charge registered on or after 6 April 2013, as it is part of the statement of particulars (see above), whether or not the charge contains a negative pledge will be clear from the register. Accordingly, any person checking the register will have actual knowledge of the negative pledge and their charge will not take priority over the floating charge containing the negative pledge. The assertion that a later fixed chargeholder who does not check the register will be held to have constructive notice of a negative pledge, in an earlier, registered floating charge, is not wholly without doubt but it is very likely that constructive notice will be found to exist. Accordingly, it is very likely that a floating charge containing a negative pledge registered on or after 6 April 2013 will take priority over a subsequently granted fixed charge.

Floating charges rank in order of time of creation: the first in time takes priority over all subsequent floating charges over the same property (Re Benjamin Cope & Sons Ltd [1914] 1 Ch 800).

Floating charges rank in order of time of creation: the first in time takes priority over all subsequent floating charges over the same property (Re Benjamin Cope & Sons Ltd [1914] 1 Ch 800).

A floating charge over specific assets may rank in priority to an earlier floating charge expressed to be a charge over all the assets and undertaking of the company (‘a general floating charge’) if power is reserved to the company in the earlier charge to create a later charge having priority (Re Automatic Bottle Makers Ltd [1926] Ch 412).

A floating charge over specific assets may rank in priority to an earlier floating charge expressed to be a charge over all the assets and undertaking of the company (‘a general floating charge’) if power is reserved to the company in the earlier charge to create a later charge having priority (Re Automatic Bottle Makers Ltd [1926] Ch 412).

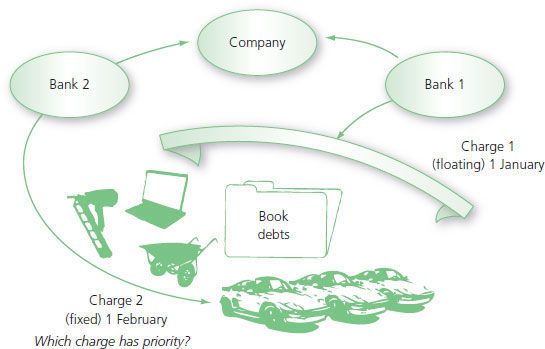

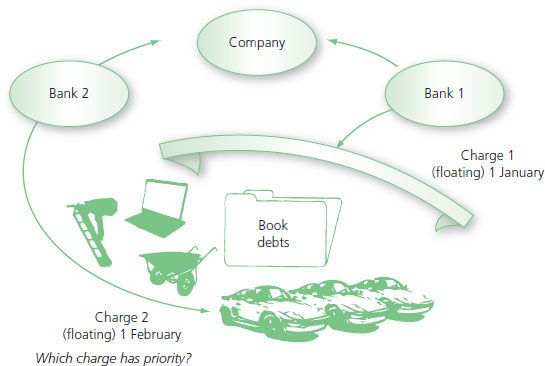

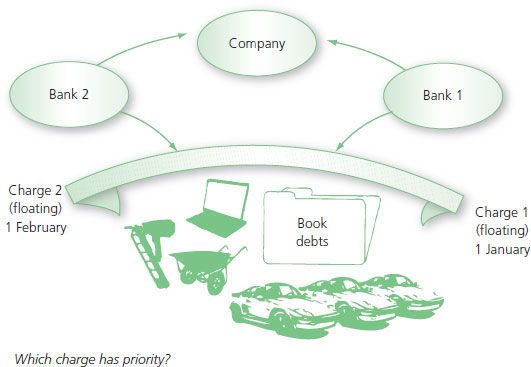

Figures 16.3 to 16.5 illustrate the operation of these rules.

Figure 16.3 Priority of charges: fixed and floating charges.

Figure 16.4 Priority of charges: two floating charges.

Figure 16.5 Priority of charges: two general floating charges.

Figure 16.3 Answer: Bank 2 has prior claim to the proceeds of sale of the premises, Re Castell & Brown Ltd [1898] 1 Ch 315. (Assuming that Charge 1 did not contain a negative pledge clause of which Bank 2 had knowledge when Charge 2 was granted.)

Figure 16.4 Answer: Bank 1 has prior claim to the proceeds of sale of the car fleet. If the document creating Charge 1 contained a clause permitting the creation of subsequent charges with priority, Charge 2 would take priority if it falls within the permission, Re Automatic Bottle Makers Ltd [1926] Ch 412.

Figure 16.5 Answer: Bank 1 has prior claim to the proceeds of sale of the assets, Re Benjamin Cope & Sons Ltd [1914] 1 Ch 800.

16.3.7 Fixed and floating charges compared and contrasted

The key differences between a fixed and floating charge are:

Whilst the floating charge remains floating (before crystallisation), the company/chargor remains free to deal with the charged property in the ordinary course of business.

Whilst the floating charge remains floating (before crystallisation), the company/chargor remains free to deal with the charged property in the ordinary course of business.

Various statutory rules are worded to apply to one form of security (e.g. floating charges) but not the other, including:

Various statutory rules are worded to apply to one form of security (e.g. floating charges) but not the other, including:

floating charge property proceeds are available to pay the expenses of winding up, preferential debts and a statutory ‘prescribed’ part is set aside for unsecured creditors out of them;

floating charge property proceeds are available to pay the expenses of winding up, preferential debts and a statutory ‘prescribed’ part is set aside for unsecured creditors out of them;

the liquidator may treat certain floating charges as invalid pursuant to s 245 of the Insolvency Act 1986.

the liquidator may treat certain floating charges as invalid pursuant to s 245 of the Insolvency Act 1986.

Priority of charges against the same property: the floating nature of the floating charge until it crystallises, results in it being treated differently from a fixed charge in determining priority of charges.

Priority of charges against the same property: the floating nature of the floating charge until it crystallises, results in it being treated differently from a fixed charge in determining priority of charges.

Note that it is common for banks to take both a fixed charge and a floating charge in the same document thereby seeking to combine the priority advantages of the fixed charge with the flexibility of the floating charge. It is instructive to look at the language actually used in such documents. In Re Spectrum (above), for example, the charge was expressed in the following language: ‘A specific charge [of] all book debts and other debts … now and from time to time due or owing to [Spectrum]’ (para 2(v)) and ‘A floating security [of] its undertaking and all its property assets and rights whatsoever and wheresoever present and/or future including those for the time being charged by way of specific charge pursuant to the foregoing paragraphs if and to the extent that such charges as aforesaid shall fail as specific charges but without prejudice to any such specific charges as shall continue to be effective’ (para 2(vii)).

liquidator

The person who undertakes the liquidation of a company and who must be a qualified insolvency practitioner