Unequal Protection for Sex and Gender Nonconformists

Chapter 11

Unequal Protection for Sex and Gender Nonconformists

Introduction

The days when only women could be flight attendants and only men could be pilots are a distant memory. The Equal Protection Clause and hundreds of federal, state, and local constitutional provisions and statutes prohibit almost all facially discriminatory regulations based on a person’s sex. The original goal of this legislation was to eliminate societal barriers to equal opportunities for men and women. When legislators adopted these statutes, however, they assumed that sex was binary and easy to establish. Therefore, they never felt the need to define the terms “male,” “female,” “sex,” and “gender.”

This failure is especially problematic for people who do not fall neatly into the male/female binary norm. Millions of people have an intersex condition or are transgender. Both groups suffer societal discrimination in a number of areas. First, people with an intersex condition and transgender people may find that government-created tests for determining their legal sex often rely on irrational contradictory factors. These tests could lead to invalidation of their marriages and their right to be considered legal parents. Second, transgender people and people with intersex traits may suffer discrimination in a variety of settings including employment, housing, and the provision of health care.

This chapter examines whether the government violates the Equal Protection Clause in two contexts: (1) when the government establishes an illogical “sex” test for determining who qualifies as a male or female, and (2) when the government discriminates against transgender people or people with an intersex condition by subjecting them to differential treatment. The second part of this chapter describes the people who suffer discrimination because of their failure to meet traditional sex and gender binary stereotypes. The third part provides an introduction to the Equal Protection Clause. The fourth and fifth parts analyze whether governmental treatment of people with an intersex condition and transgender people violates the Equal Protection Clause. The fourth part focuses on state-created sex classification systems and explains why current government “sex” tests do not meet the rigorous review standard mandated by intermediate scrutiny. The fifth part examines sex discrimination jurisprudence and concludes that differential governmental treatment of people with an intersex condition or transgender people constitutes impermissible “sex” discrimination. This chapter concludes that sex classification systems and other governmental acts that rely on sex and gender stereotypes violate the Equal Protection Clause.

Sex and Gender Nonconformists

Courts have relied on inaccurate sex and gender stereotypes when they have determined whether a person qualifies as a male or female or whether someone has been subjected to discrimination because of “sex.” This section explains why sex-based binary classification systems based on sex and gender stereotypes do not reflect reality for the millions of people who have an intersex condition or who are transgender.

People with an Intersex Condition or Difference of Sex Development (DSD)

Millions of people do not have sex markers that are all clearly male or clearly female. They have what is known as an intersex condition, or DSD.1 Although doctors and activists in the intersex community continue to debate exactly what conditions qualify as “intersex,” the term is often used to include anyone with a congenital condition whose sex chromosomes, gonads, or internal or external sexual anatomy do not fit clearly into the binary male/female norm.2

Some intersex conditions involve an inconsistency between a person’s internal and external sex features. For example, some people with an intersex condition may have a female body type, female-appearing external genitalia, no internal female organs, and testicles.3 Other people with an intersex condition may be born with external genitalia that do not appear to be clearly male or female. For example, a girl may be born with a larger than average clitoris and no vagina.4 Similarly, a boy may be born with a small penis or no penis.5 Some people with an intersex condition may also be born with a chromosomal pattern that does not fall into the binary XX/XY norm.6

Not all intersex conditions are apparent at the time of birth; some conditions become evident as a child matures.7 In some conditions, a child whose genitalia appeared to be female at birth will masculinize in puberty.8 Other intersex conditions may be discovered at puberty when the adolescent fails to develop typical male or female traits. For example, the condition may be discovered when a girl reaches puberty and fails to menstruate.9

Because experts do not agree on exactly which conditions fit within the definition of intersexuality and some conditions are not evident until years after a child is born, it is impossible to state with precision exactly how many people have an intersex condition. Most experts agree, however, that approximately 1–2 percent of people are born with sexual features that vary from the medically defined norm for male and female.10 These variations may relate to chromosomal structure, internal reproductive organs, or external genitalia. Children with ambiguous external genitalia are not as common. Approximately one in 1,500 to one in 2,000 births involve a child who is born so noticeably atypical in terms of external genitalia that a specialist in sex differentiation is consulted and surgical alteration of the external genitalia is considered.11

The term “intersex” itself is controversial. Many doctors favor abandoning the term “intersex” in favor of the term “disorder of sex development” (DSD). Some who support the use of DSD terminology have argued that the term “disorder” should be dropped and the initial “D” should stand for difference rather than disorder.12

Transsexuality and Transgenderism

Some people are confused about how intersexuality compares to transsexuality and transgenderism. Generally, intersexuality refers to a condition in which a person’s biological sex markers are not all clearly male or female, while transgenderism and transsexuality are used to describe behaviors or identities of people whose gender expression, gender identity, or both, do not necessarily conform with the binary sex norm or may be different from the sex assigned to them at birth.13 Not all communities use the terms “transgender” and “transsexual” consistently and different groups and individuals have strong feelings about which term they prefer.

One major LGBT organization, GLAAD, suggests the following definitions:

Transgender: An umbrella term (adj.) for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. The term may include but is not limited to: transsexuals, cross-dressers and other gender-variant people. Transgender people may identify as female-to-male (FTM) or male-to-female (MTF) … Transgender people may or may not decide to alter their bodies hormonally and/or surgically.

Transsexual (also Transexual): An older term which originated in the medical and psychological communities. While some transsexual people still prefer to use the term to describe themselves, many transgender people prefer the term transgender to transsexual. Unlike transgender, transsexual is not an umbrella term, as many transgender people do not identify as transsexual.14

The University of San Francisco Medical Center defines the terms as follows:

Transgender: literally “across gender”; sometimes interpreted as “beyond gender”; a community-based term that describes a wide variety of cross-gender behaviors and identities. This is not a diagnostic term, and does not imply a medical or psychological condition.

…

Transsexual: a medical term applied to individuals who seek hormonal (and often, but not always) surgical treatment to modify their bodies so they may live full time as members of the sex category opposite to their birth-assigned sex (including legal status). Some individuals who have completed their medical transition prefer not to use this term as a self-referent.15

Experts differ on the prevalence of transgenderism. Numbers from recent studies range from a low of 1 in 104,000 to a high of 1 in 200.16

Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is determined by the person’s sexual attraction. Heterosexuals are sexually attracted to the “opposite” sex. Gays and lesbians are sexually attracted to people of the “same” sex. Bisexuals are sexually attracted to people of “both” sexes.

Society and legal institutions often inappropriately conflate the distinct concepts of biological sex, gender identity, and sexual orientation. Biological sex features do not necessarily dictate a person’s gender identity. Similarly, biological sex features and gender identity do not necessarily control a person’s sexual orientation.

Most people meet societal sex and gender stereotypes; their sex markers are all congruent, they self-identify as the gender assigned to them at birth, and they are heterosexual. Millions of people, however, do not fit this stereotype. A person born with all male biological sex features may have a female gender identity and may live as a female. That same person, however, may be sexually attracted to women. In other words, a natal male may choose to live as a female, but may still prefer to have sex with another woman. Biological sex does not control gender identity, and neither biological sex nor gender identity can be used to predict a person’s sexual orientation.

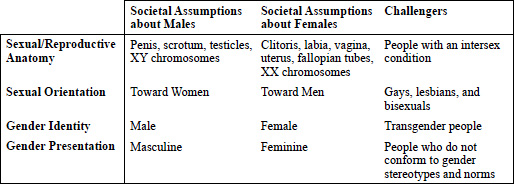

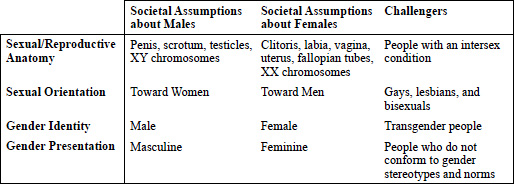

The following chart illustrates prevailing societal presumptions about men and women and the groups that directly challenge those assumptions.

Because lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people (LGBTs), and people with an intersex condition do not fit societal binary sex and gender norms, they suffer from pervasive discriminatory practices.17 The Equal Protection Clause protects people from “invidious discrimination in statutory classifications and other governmental activity.”18 Thus, transgender people and people with an intersex condition may be able to bring equal protection claims based on government-created sex classification systems and other governmental activity that results in discrimination because of sex.

An Introduction to the Equal Protection Clause

The purpose of the Equal Protection Clause is to ensure that the government does not subject its citizens to arbitrary classifications.19 Depending on the classification at issue, the Supreme Court will apply one of three levels of scrutiny to the government action: strict scrutiny, intermediate scrutiny, or rational basis review. Under each level, the court will apply a two-step analysis. First, it will assess the government purpose for the classification. If the government purpose is considered valid, the court will then analyze the relationship between the government purpose and the means used to accomplish the government’s goal.

The Supreme Court applies strict scrutiny when the discrimination involves a suspect classification.20 The Court has applied strict scrutiny to governmental classification systems based upon race, national origin, and sometimes alienage.21 Under strict scrutiny analysis, the court places the burden on the government to prove that: (1) it has a compelling interest for its classification and (2) the means the government has chosen to accomplish the compelling goal are narrowly tailored for that purpose.22 Most state actions cannot survive strict scrutiny because few government justifications qualify as compelling and the means used to accomplish the governmental goal are subject to a searching judicial inquiry.23

Sex classifications are subject to an intermediate level of review.24 Sex-based classifications require that the government prove: (1) an important or exceedingly persuasive justification for its classification and (2) that the means used to accomplish the important justification are substantially related to the government’s goal.25 Although intermediate scrutiny is technically less demanding than strict scrutiny, most government sex-based classifications also fail equal protection requirements.

Courts apply the lowest level of review, rational basis review, to all other legislative classifications.26 Under rational basis analysis, a challenger must prove that either: (1) no legitimate governmental objective for the government classification exists, or (2) rational means are not used to achieve a legitimate governmental objective.27 It is easy to establish that a legitimate purpose exists and rational means were used to accomplish that purpose. Therefore, almost all government classifications are considered constitutional under this low level of review.28

Although the Supreme Court has formally recognized only three levels of scrutiny, in recent cases the Court seems to be applying a form of heightened rational basis review, often referred to as rational basis with bite, when determining whether classifications based on sexual orientation violate the Equal Protection Clause.29 Under a rational basis with bite analysis, the Court has struck down government classifications that are motivated by “a bare desire to harm a politically unpopular group.”30

Transgender people and people with an intersex condition may bring an action for violation of their right to equal protection in two scenarios. First, when the government establishes tests for determining whether a transgender person or a person with an intersex condition is a male or a female and thus qualifies for a sex-based right, the government is creating a sex classification system that may violate the Equal Protection Clause. Second, when a government actor engages in discrimination against people based on their transgender or intersex status, the government may be engaged in impermissible sex discrimination under the Equal Protection Clause.31

Governmental Sex Classification Systems that Rely on Chromosomes, the Ability to Reproduce, Religious References, or Gender Stereotypes to Determine who Qualifies as a Male or Female Violate the Equal Protection Clause

Very few laws in the United States differentiate between men and women. The only major areas where a person’s sex is legally significant is in the context of marriage and the use of gender-segregated facilities such as restrooms, locker rooms, and housing in college dormitories and prisons.32

Some states still define marriage as a union of one man and one woman and refuse to recognize marriages between people of the same sex.33 Until 2013, the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA)34 also limited the definition of marriage for federal purposes to “one man and one woman.” In 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the portion of DOMA that denied validly married same-sex couples the same federal rights as opposite-sex married couples was unconstitutional.35 The Court declined to rule on whether all state laws limiting the right of same sex couples to marry are unconstitutional.36 The Court had an opportunity to review this issue again during its 2014 term, but it refused to grant certiorari in a number of cases involving same-sex marriages.37 In 2015, the Supreme Court granted certiorari in four same-sex marriage cases.38 If the Supreme Court fails to rule in these cases that all states must allow same-sex couples to wed, people who are considered the same sex will continue to be barred from marrying in some states.

Even if the Supreme Court mandates same-sex marriage in all states, sex determination will still be important because public spaces including restrooms, dressing rooms, and locker rooms remain segregated by sex. In addition, state universities and prisons determine housing based on a person’s sex.

As long as state laws continue to differentiate between men and women, legal institutions will be required to determine exactly what makes a man a man and what makes a woman a woman. Thus far, state legislatures have failed to include tests for determining a person’s sex in their marriage statutes. Instead, they have left it to the courts to determine a person’s legal sex when a marriage is challenged based upon a person’s inability to qualify as a husband or wife.39 In other areas, such as restroom use, some states have proposed specific “sex” tests for purposes of determining access to sex-segregated facilities.40 When courts and legislatures create tests for establishing a person’s legal sex, the tests must not violate the right to Equal Protection.

Government Tests that Determine whether Someone Qualifies as a Man or a Woman are Sex Classification Systems that Must Survive Intermediate Level Scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause

When courts or legislatures establish a person’s legal sex, they are creating a sex classification system. To pass constitutional scrutiny, such tests should be subjected to heightened scrutiny because the government is establishing a sex-based classification system.41

Since the 1970s, transgender people have argued that state sex classification systems that ignore a person’s gender self-identity violate the Equal Protection Clause.42 In the early cases, the courts inappropriately analyzed whether individuals who “change their sex” are entitled to a heightened level of scrutiny as a suspect class.43 These courts universally determined that transsexuals were not a suspect class and thus government classifications systems that treated transsexuals as their birth sex, as opposed to the sex that accords with their gender identity, did not violate the Equal Protection Clause under rational basis review.44

The courts in these early cases were not focusing on the appropriate issue. The critical question to ask is not whether the discriminated-against group is suspect; it is whether the state is employing a classification system that is suspect. The appropriate level of scrutiny to apply should not be based on whether people who “change their sex” have been determined to be a “suspect group”; it should be based upon whether the state is creating a suspect classification system.45

For example, if a state determines that a person with female-appearing genitalia and breasts is a male because she has XY (male) chromosomes, the state is establishing a chromosomal test for determining sex. Such a test must survive heightened scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause. An analysis of the scenario presented to the court in Kansas46 illustrates why these determinations should be treated as sex-based classifications subject to intermediate scrutiny. J’Noel Gardiner, a male-to-female transgender person, amended her Wisconsin birth certificate and other official documents to indicate that she is a female. When J’Noel wanted Kansas to recognize her Wisconsin birth certificate and treat her as a female for purposes of determining the validity of her marriage, the Kansas court refused to do so. To reach this conclusion, the court needed to establish a test to determine whether J’Noel qualified as a male or a female.

In reaching its conclusion that J’Noel was legally a man, the court relied on Webster’s dictionary to determine J’Noel’s sex. According to the court:

Webster’s New Twentieth Century Dictionary (2nd ed.1970) states … “[m]ale” is defined as “designating or of the sex that fertilizes the ovum and begets offspring: opposed to female.” “Female” is defined as “designating or of the sex that produces ova and bears offspring: opposed to male.”47

Under this test, the court determined that J’Noel was a male.48 If instead, the Kansas court had been asked to determine the legal sex of Jennifer, a woman born in Wisconsin and identified as a female at birth, Kansas would have recognized Jennifer’s status as a female, even if Jennifer had been unable to bear children. In both scenarios, Kansas would be creating rules to establish who qualifies as a woman to determine who is entitled to become a legal wife. It would thus be creating a sex-based classification system that is valid only if it satisfies intermediate scrutiny.

Under intermediate scrutiny, the state must establish an important or exceedingly persuasive justification for its classification system49 and the chosen definition may not be based on administrative convenience or stereotypes of what it means to be a “real” woman.50

Rules that Bar Transgender People or People with an Intersex Condition from Marrying in the Gender Role that Comports with their Gender Self-Identity Violate the Equal Protection Clause

The state’s interest in creating marriage sex tests is not important or exceedingly persuasive If states are allowed to limit marriage to one man and one woman,51 they will also need to establish a test for determining who qualifies as a man or a woman if one of the spouses is transgender or has an intersex condition.52 A number of courts have established tests for determining a person’s sex for purposes of marriage. These cases all involved marriages in which one of the spouses was transgender.53

A California trial court,54 a New Jersey Appellate Court,55 a federal district court interpreting Minnesota law,56 and an immigration court interpreting North Carolina law57 ruled that the transgender spouses had legally changed their sex and that their unions were valid marriages.58 The Supreme Court of Kansas,59 the Court of Appeal of Florida,60 the Court of Appeals of Texas,61 the Court of Appeals of Ohio,62 the Appellate Court of Illinois,63 and two lower courts in New York64 ruled that the sex assigned at birth had not changed and the marriages involving transgender spouses were invalid. In reaching these decisions, the courts relied on chromosomal makeup,65 reproductive capacity,66 and religious references67 to determine a person’s legal sex.

In the cases that refused to recognize the transgender spouses’ self-identified gender as their legal sex for purposes of marriage, the courts relied on three purported state interests to justify their rulings: (1) the state’s public policy against same-sex marriage,68 (2) the inability of a post-operative transgender person to engage in procreative intercourse,69 and (3) the inability of a state to change the sex fixed by “our Creator.”70

Although few courts have expressly relied on their public policy against same-sex marriages, the courts that have denied the right of transgender people to marry in the role that comports with their gender self-identity have all cited their state’s law prohibiting marriages of two people of the same sex.71 At least one court has expressly used its view on same-sex marriage to justify denying a female-to-male transgender person the right to marry as a man.72 In In re Nash, Jacob Nash’s birth certificate indicated that he was a male, but the Ohio Court of Appeals concluded that the state was not obligated to issue a marriage license to Jacob and his future wife because the state would then be issuing a marriage license to a same-sex couple.73

In other words, the Ohio court decided to ignore the sex designation on Jacob’s amended birth certificate and instead determined that Jacob was female. The Ohio court’s reasoning on this matter was circular. A court cannot use a public policy against same-sex marriage to invalidate a marriage until after it determines the sex of the parties. Jacob’s marriage is a same-sex marriage only if he is legally a woman. Whether Jacob is a man or a woman for purposes of marriage depends upon how the state determines a person’s sex. Thus, Ohio’s public policy against same-sex marriage could not be used to determine Jacob’s sex.

A few courts have focused on the inability of transgender people to engage in procreative sexual intercourse.74 The Kansas Supreme Court focused on the inability of transgender people to reproduce offspring when it invalidated a marriage in which the wife was transgender.75 The court created a sex classification system that relied on dictionary definitions of sex. The dictionary provided that males are the sex that fertilize the ovum and beget offspring and females are the sex that produce ova and bear offspring.76 This justification is unlikely to survive even rational relationship review under the Equal Protection Clause because no state requires proof of fertility as a condition of marriage.77 Furthermore, because transgender people who have undergone surgery and hormonal treatment can neither bear nor beget, reliance upon the ability to reproduce implies that transgender people are neither males nor females and thus would be barred from marrying anyone. Denying transgender people the right to marry because of their infertility violates their fundamental right to marry.78

One state, Texas, refused to treat a male-to-female transgender person as a woman by ruling that medicine and law cannot change the sex that was “immutably fixed by our Creator at birth.”79 State actions based solely on religious justifications are unconstitutional.80 States cannot use religion to justify their actions in the absence of a neutral secular basis for their decisions.81 Vague religious references cannot qualify as an important government interest under the Equal Protection Clause.82

Refusing to recognize people’s self-identified sex as their legal sex for purposes of marriage based on reproductive incapacity or religious references cannot be considered important or exceedingly persuasive justifications that can withstand equal protection intermediate level scrutiny. It is also questionable whether they would even be considered legitimate state interests under the lower level rational basis analysis.83 Until the United States Supreme Court resolves the issue, states could continue to argue that the state’s interest in limiting marriage to one man and one woman qualifies as an important state interest.84 Courts cannot use the state’s interest in limiting marriage to heterosexual unions, however, to determine that transgender people are barred from marrying in the gender role that matches their self-identity. Instead, the court must establish a “sex test” that is substantially related to the state’s interest in limiting marriages to one man and one woman.

Marriage sex tests that rely on chromosomal analysis and reproductive incapacity are not substantially related to an important government interest In the event that a court finds that any of the state interests discussed above qualify as important government interests, the court must still examine the means the state uses to accomplish the government’s goal.85 To pass intermediate scrutiny, the means used must be substantially related to the important government goal and cannot be based on gender stereotypes.86

Courts are divided about the test to use to determine a person’s legal sex. Some jurisdictions focus on gender self-identity while other jurisdictions rule that transgender people forever remain the sex assigned to them at birth.

Jurisdictions that emphasize gender self-identity as the only factor or the critical factor for determining a person’s legal sex for purposes of marriage rely on scientific developments regarding sex and gender formation. These jurisdictions acknowledge that a number of factors could be used to determine a person’s sex, including chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, hormones, phenotype, assigned sex, and gender self-identity.87 In focusing on gender self-identity, these jurisdictions recognize the complex nature of sex and gender formation and their court decisions reflect current scientific knowledge on the subject.

Studies support the finding that transgenderism has a biological basis.88 More important, standard medical protocol recognizes that there is no “cure” for transgenderism; the appropriate treatment for transgender people is to facilitate their wellbeing in their gender self-identity. Experts recommend that transgender individuals live in their self-identified gender role.89

Courts and legislatures in jurisdictions that understand the nature of transgenderism have recognized the right of transgender people to have their gender self-identity legally recognized. For example, in 2002, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that states that deny transgender people the right to be recognized as their self-identified sex violate Article 8 (relating to the right to privacy) and Article 12 (relating to the right to marry and found a family) of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.90 In 2004, the European Court of Justice issued a similar ruling.91 In 2004, Great Britain, which for decades had been one of the countries that provided sparse protection to transgender people, passed sweeping legislation to provide them legal rights that recognize and protect their ability to be legally recognized as their self-identified sex.92 A number of courts in the United States have adopted this approach.93

Other jurisdictions in the United States, however, have rejected gender self-identity as the test to determine a person’s legal sex for purposes of marriage and instead have ruled that transgender people remain the sex assigned to them at birth.94 To reach this conclusion, the courts relied on biological factors,95 including chromosomes,96 the absence of internal reproductive organs,97 and the inability to reproduce.98 To be constitutional under the Equal Protection Clause, the state must prove that its sex text—chromosomes, the absence of internal sex organs, or the inability to reproduce—accomplishes the important interest articulated by the state.

As discussed in the previous section, courts have asserted that three interests justify their refusal to recognize people’s self-identified sex as their legal sex for purposes of marriage: (1) reproductive incapacity, (2) religious references, and (3) maintaining marriage as a heterosexual union of one man and one woman. The first two articulated state interests, reproductive capacity and religious references cannot be considered important or for that matter legitimate state interests.99

If the Supreme Court allows states to continue to bar same-sex couples from marrying, states may continue to argue that the state’s interest in limiting marriage to one man and one woman qualifies as an important state interest.100 But the tests that the courts have used to determine a person’s sex do not pass equal protection scrutiny because they are not substantially related to the articulated state interest in deterring same-sex marriages. Some jurisdictions that have ruled that post-operative male-to-female transgender people are still males for the purposes of marriage are allowing post-operative male-to-female transgender people to marry women. In other words, two individuals who both appear to be women (even when they are undressed) are now legally allowed to marry each other in these jurisdictions that otherwise ban same-sex marriages.101

These tests are also invalid because they rely on false sex stereotypes, which cannot be used to justify a state sex classification system.102 When a state determines that it will classify only those individuals who are able to bear children, who have XX chromosomes, or who have a uterus and ovaries as women, it is engaging in impermissible sex stereotyping about what it means to be a “real” woman. These and other biologic tests effectively ignore scientific literature that clearly establishes that sex features are not binary and many people have incongruent sex attributes.103

Ability to reproduce, internal reproductive organs, and chromosomal structure are not more valid indicators of a person’s sex than any other anatomical or physiological sex factors. For example, if a state adopted a sex determination test that defined men according to the size of their penis and women according to the size of their breasts, it would undoubtedly fail even the rational basis test. Although chromosomal make-up and ability to reproduce may be less variable than penis and breast size, courts relying on these sex indicators are still basing their determination on sex stereotypes. These stereotypes cannot be used to uphold a sex-based classification under the Equal Protection Clause. A sex classification system that rejects scientific developments in favor of stereotypes should be declared unconstitutional because the state can neither articulate an important state interest to support its system nor prove a substantial relationship between the state’s interest and the means it uses to accomplish that interest.104

State sex classification systems that rely on chromosomal structure, the absence of internal sex organs, and reproductive incapacity to determine the validity of a marriage fail even rational basis scrutiny Even if a court were to determine that rational basis review is appropriate, states that have excluded scientific advances about sex and gender identity formation in favor of tests based solely on reproductive capacity, the absence of internal sex organs, or chromosomal structure would not pass rational basis scrutiny under recent U.S. Supreme Court equal protection jurisprudence. The United States Supreme Court’s decisions in Romer v. Evans105 and United States v. Windsor106 suggest that, when examining laws purporting to violate the constitution under rational basis review, the Supreme Court may be moving toward affording greater protection to sexual minorities. Although the Court did not specifically rule that classifications harming sexual minorities should be subjected to heightened scrutiny, the court applied a more searching type of review in these cases. Some federal courts have interpreted the Court’s decision in Windsor to require heightened scrutiny in cases involving classifications based on sexual orientation.107

In Romer, Colorado citizens voted to amend the Colorado Constitution to preclude all legislative, executive, or judicial action designed to protect the status of people based on their homosexual, lesbian or bisexual orientation, conduct, practices, or relationships. The Supreme Court found that this amendment violated the Equal Protection Clause because it imposed a broad and undifferentiated disability on a single group.108 Furthermore, the Court found that the amendment was motivated by animus toward a particular group and it lacked a rational relationship to legitimate state interests. As the court stated: “[I]f the constitutional conception of ‘equal protection of the laws’ means anything, it must at the very least mean that a bare … desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate governmental interest.”109

The Court reinforced these principles in 2013, in United States v. Windsor, when it struck down DOMA, a federal law denying same-sex married couples federal rights granted to opposite-sex married couples. The Court found that in determining whether a law is motivated by an improper animus or purpose, the court must carefully consider “[d]iscriminations of an unusual character.”110

Therefore, even when analyzed under the lowest standard of review, states that refuse to recognize the right of transgender people to marry in the role that matches their self-identified sex may violate equal protection guarantees. When a state defines “male” and “female” in a way that is contrary to current science and visits a broad disability on transgender people, the state’s action appears to evidence a bare “desire to harm a politically unpopular group.”111 Furthermore, the state cannot justify its decision on its public policy disfavoring same-sex marriages because its sex determination ruling in effect sanctions what appears to be a same-sex marriage. For example, if J’Noel Gardiner, a male-to-female transgender person with breasts and female appearing genitalia, is legally allowed to marry another woman, to most of society it would appear to be a same-sex union.112 Thus, no rational relationship exists between a state sex classification system that relies solely on chromosomes or ability to reproduce and its interest in limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples.

Refusing to allow transgender people to marry in the gender role in which they live indicates that the state action is based solely on an irrational animus against a discrete group. When a state denies transgender people the right to marry in their self-identified gender role, the state is inhibiting personal relationships and the denial suggests the intent to deny equal protection to a politically unpopular group. This type of animus has led the Supreme Court to strike down laws even under a rational basis level of review, concluding, for example, that the bare “desire to harm a politically unpopular group” was not a legitimate interest when it involved hippies,113 people with a mental or emotional impairment,114 or gays and lesbians.115 Limiting transgender people’s right to marry in accord with their gender identity appears “not to further a proper legislative end, but to make them unequal to everyone else.”116

The rational basis test the Court applied in Romer and Windsor supports the conclusion that state classification systems that discriminate against individuals who fail to conform to chromosomal or reproductive gender norms are unconstitutional even under rational basis review. If these state classifications fail to survive rational basis review, they would clearly fail under the heightened level of scrutiny traditionally applied to sex and gender classifications.

Rules that Bar Transgender People or People with an Intersex Condition from Accessing the Restrooms, Locker Rooms, and Housing that Comports with Their Gender Self-Identity May Violate the Equal Protection Clause

Restrooms and locker rooms Recently, some states have proposed bills that would bar people from accessing single-sex facilities if the person was not born a “biological member of that sex.”117 According to a Florida bill, the state’s interests in creating such legislation include protecting the public’s expectation of privacy in single-sex facilities, protecting users from exposure to people of the “opposite sex,” and protecting the public in places of increased vulnerability where they could be subjected to assault, battery, molestation, rape, voyeurism, and exhibitionism.118

Assuming these purposes would qualify as “important” state interests,119