Undue Influence

11

Undue Influence

Contents

11.4 Presumed influence: recognised relationships

11.5 Presumed influence: other relationships

11.6 Relevance of the disadvantageous nature of the transaction

11.7 Summary of current position on presumed undue influence

11.8 Undue influence and third parties

11.9 Remedies for undue influence

11.10 Unconscionability and inequality of bargaining power

Undue influence is the equitable concept which supplements the common law vitiating factor of duress. It operates largely through the application of presumptions. The following aspects are discussed in this chapter:

The underlying principles. When does influence become ‘undue’? Imbalance of power between the parties is an important element in identifying undue influence.

The underlying principles. When does influence become ‘undue’? Imbalance of power between the parties is an important element in identifying undue influence.

Actual undue influence. If there is direct evidence that a party agreed to a contract under the influence of improper pressure at that time, this will constitute actual undue influence. Such evidence is, however, rare.

Actual undue influence. If there is direct evidence that a party agreed to a contract under the influence of improper pressure at that time, this will constitute actual undue influence. Such evidence is, however, rare.

Presumptions. A relationship of influence will be presumed where:

Presumptions. A relationship of influence will be presumed where:

the parties are in one of a number of recognised relationships (for example, solicitor–client); the presumption is in these circumstances irrebuttable;

the parties are in one of a number of recognised relationships (for example, solicitor–client); the presumption is in these circumstances irrebuttable;

the relationship between the parties has developed in a way that leads to one party dominating the other; this type of presumption may be rebutted by evidence to the contrary.

the relationship between the parties has developed in a way that leads to one party dominating the other; this type of presumption may be rebutted by evidence to the contrary.

Disadvantageous transactions. Where a contract between parties in a relationship of presumed influence clearly operates to the disadvantage of the weaker party, then undue influence will be presumed. It will be up to the alleged influencer to demonstrate that the other party entered into the contract with a full appreciation of what was involved (for example, after receiving independent legal advice).

Disadvantageous transactions. Where a contract between parties in a relationship of presumed influence clearly operates to the disadvantage of the weaker party, then undue influence will be presumed. It will be up to the alleged influencer to demonstrate that the other party entered into the contract with a full appreciation of what was involved (for example, after receiving independent legal advice).

Effects. A contract entered into on the basis of actual or presumed influence is voidable. The usual bars to rescission apply (for example, lapse of time, third party rights). No damages are available.

Effects. A contract entered into on the basis of actual or presumed influence is voidable. The usual bars to rescission apply (for example, lapse of time, third party rights). No damages are available.

Third parties. Where a debtor has persuaded a person to act as surety or guarantor, the creditor will be put on notice whenever the relationship between debtor and surety is non-commercial (for example, husband persuading wife to use the family home as security for business debts). In that situation:

Third parties. Where a debtor has persuaded a person to act as surety or guarantor, the creditor will be put on notice whenever the relationship between debtor and surety is non-commercial (for example, husband persuading wife to use the family home as security for business debts). In that situation:

the creditor will be affected by any undue influence used by the debtor; the transaction may be voidable on that basis;

the creditor will be affected by any undue influence used by the debtor; the transaction may be voidable on that basis;

the creditor can protect itself by insisting that the surety receives legal advice before entering into the transaction.

the creditor can protect itself by insisting that the surety receives legal advice before entering into the transaction.

Unconscionability. English law recognises no general concept of unconscionability.

Unconscionability. English law recognises no general concept of unconscionability.

Duress, as discussed in the previous chapter, is essentially a common law concept. Alongside it must be placed the equitable doctrine of ‘undue influence’. This operates to release parties from contracts that they have entered into,1 not as a result of improper threats, but as a result of being ‘influenced’ by the other party, whether intentionally or not.2

One of the main difficulties with undue influence, as with duress, is to find the limits of legitimate persuasion. If it were impermissible to seek to persuade, cajole or otherwise encourage people to enter into agreements, then sales representatives would all be out of a job. ‘Influence’ in itself is perfectly acceptable: it is only when it becomes ‘undue’ that the law will intervene. Clarity in deciding when that has occurred is not assisted by the fact that the word ‘undue’ has two potential meanings. It can be used to indicate some impropriety on the part of the influencer. The influence is ‘undue’ because an imbalance of power between the parties has been used illegitimately by the influencer. Alternatively, the word can be used simply to indicate that the level of influence is at such a level that the influenced party has lost autonomy in deciding whether to enter into a contract. This does not imply any necessary impropriety on the part of the influencer. The point has been recognised in the High Court of Australia, where ‘undue’ has been given the second meaning, and undue influence distinguished from unconscionable conduct. As Deane J put it:3

Undue influence, like common law duress, looks to the quality of the consent or assent of the weaker party … Unconscionable dealing looks to the conduct of the stronger party in attempting to enforce, or retain the benefit of a dealing with a person under a special disability in circumstances where it is not consistent with equity or good conscience that he should do so.

English courts, however, have tended to emphasise the wrongdoing of the stronger party in undue influence cases, though it cannot be said that their approach is consistent, and there are undue influence cases which indicate that such wrongdoing is not an essential element.4 The issue is whether the concept is ‘claimant-focused’ or ‘defendant-focused’.5 If it is claimant-focused, then what matters is whether the claimant acted autonomously in entering into the contract; if it is defendant-focused, then what matters is whether the defendant has deliberately taken advantage of the claimant’s weaker position. As suggested above, the English courts have not consistently applied one approach or the other, and this adds to the uncertainty about the precise scope of the concept. The most recent House of Lords decision, Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2),6 adopts what is primarily a defendant-focused analysis, based on whether there has been ‘abuse’ of a position of influence, and this seems to be the dominant approach.7

How, then, do the courts decide when influence has overstepped the limits of acceptability and become ‘undue’? The basic test in English law is that it is only where there is some relationship between the parties (either continuing, or in relation to a particular transaction) which leads to an inequality between them that the law will intervene. The starting point for the law’s analysis is therefore not the substance of the transaction, but the process by which it came about. Was this the result of a person who was in a position to influence the other party by abusing that relationship in some way? An initial task is therefore to identify which relationships will give rise to this inequality. Once they have been identified, then further questions will arise as to how the doctrine applies to them.

11.2.1 IN FOCUS SCOPE OF UNDUE INFLUENCE

The precise scope of the concept of undue influence may be due for reconsideration. At present, there are authorities which are treated as being concerned with undue influence, largely because of the limited scope given to duress at the time they were decided. In Williams v Bayley,8 for example, the plaintiff had agreed to give a mortgage over his colliery as security for debts incurred by his son, who had forged his father’s signature on promissory notes. The creditors had threatened that the son would be prosecuted if the mortgage was not given.9 The agreement was set aside as being obtained by undue influence. Similarly, in Mutual Finance Ltd v John Wetton & Sons Ltd,10 implied, though not explicit, threats to prosecute a member of a family company in relation to a forged guarantee led to the company giving a new guarantee.11 This was again set aside on the basis of undue influence. Both these cases involve ‘pressure’ being placed on a party in much the same way as occurs with duress. It is possible that the expansion in the type of threats which are now treated as potentially giving rise to duress12 would mean that they would be put in that category. There is still the difficulty, however, that the courts seem reluctant to extend duress to implied rather than explicit threats. There is a strong argument that all these situations, involving pressure resulting from express or implied threats, might be usefully recategorised as ‘duress’, leaving ‘undue influence’ to deal with relationships where one party has lost autonomy because of his or her relationship with the ‘influencer’.13 At the moment, the courts have not been prepared to take such a step.

11.2.2 THE MODERN LAW OF UNDUE INFLUENCE

The whole area of undue influence has twice in the last 20 years been given a thorough examination by the House of Lords – in 1993, in Barclays Bank plc v O’Brien,14 and in 2001, in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2).15 Between these two decisions there were many Court of Appeal decisions, mainly concerned with the situation where a bank is infected by the undue influence of a husband who has persuaded his wife to use the matrimonial home as security for a business loan. Most of this case law is, following Etridge, of historical interest only, but one or two of the decisions are worthy of note. The main focus in the rest of this chapter will, however, be on the views of the House of Lords as expressed in O’Brien and Etridge.

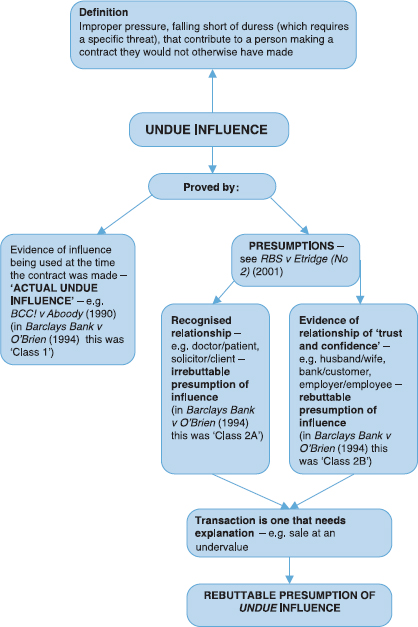

In the leading speech in O’Brien, Lord Browne-Wilkinson adopted the analysis of the Court of Appeal in Bank of Credit and Commerce International SA v Aboody16 to the effect that there are two main categories of undue influence, the second of which must be divided into two further separate subcategories. The categories were actual undue influence (described as ‘Class 1’) and presumed undue influence (described as ‘Class 2’). Presumed undue influence was then subdivided into influence arising from relationships (such as solicitor–client, doctor–patient) which will always give rise to a presumption of undue influence (‘Class 2A’) and influence arising from relationships which have developed in such a way that undue influence should be presumed (‘Class 2B’). These divisions have subsequently been used in many cases. The House of Lords took the view, however, in Royal Bank of Scotland v Etridge (No 2)17 that, while there is a distinction between ‘actual’ and ‘presumed’ influence, it should not operate quite as suggested by the categorisation adopted in O’Brien and that, in particular, the concept of Class 2B influence is open to misinterpretation.18

The concept of ‘actual undue influence’ will be considered first, followed by ‘presumed undue influence’, and the review of this area by the House of Lords in Etridge.

In relation to actual undue influence, the claimant must prove, on the balance of probabilities, that in relation to a particular transaction, the defendant used undue influence. There is no need here for there to be a previous history of such influence. It can operate for the first time in connection with the transaction which is disputed. An example of this type of influence is to be found in BCCI v Aboody.19 Mrs Aboody was 20 years younger than her husband. She had married him when she was 17. For many years, she signed documents relating to her husband’s business, of which she was nominally a director, without reading them or questioning her husband about them. On the occasion which gave rise to the litigation, she had signed a number of guarantees and charges relating to the matrimonial home, in order to support loans by the bank to the business. She had taken no independent advice, though the bank’s solicitor had at one meeting attempted to encourage her to take legal advice. During that meeting, Mr Aboody, in a state of some agitation, came into the room and, through arguing with the solicitor, managed to reduce his wife to tears. It was held that although Mr Aboody had not acted with any improper motive, he had unduly influenced his wife. He had concealed relevant matters from her, and his bullying manner had led her to sign without giving proper detached consideration to her own interests, simply because she wanted peace.

The Court of Appeal in this case, following dicta of Lord Scarman in National Westminster Bank plc v Morgan,20 held that Mrs Aboody’s claim to set aside the transaction nevertheless failed, because it was not to her ‘manifest disadvantage’. The loans which she was guaranteeing had, in fact, given the company a reasonably good chance of surviving, in which case the potential benefits to Mrs Aboody would have been substantial. The risks involved did not, therefore, clearly outweigh the benefits. The House of Lords, in CIBC Mortgages plc v Pitt,21 subsequently indicated, however, that it is not a requirement in cases of actual undue influence that the transaction is disadvantageous to the victim. If similar facts were to recur, therefore, a person in the position of Mrs Aboody would be likely to succeed in having the transactions set aside. A person is entitled to have a contract set aside if they have been bullied into making it, notwithstanding they may receive some benefit from it.

Where actual undue influence is proved it is not necessary for the claimant to prove that the transaction would not have been entered into but for the improper influence. This was the view of the Court of Appeal in UCB Corporate Services Ltd v Williams.22 The position is analogous to that applying to misrepresentation or duress: as long as the influence was one factor in making the decision to enter into the transaction, that is sufficient.23

Under the O’Brien analysis there were certain relationships which were presumed to give rise to undue influence. The current position as set out by the House of Lords in Etridge is that such relationships give rise to a presumption of influence but not necessarily undue influence. They are relationships ‘where one party is legally presumed to repose trust and confidence in the other’.24 As Lord Nicholls put it:25

The relationships which fall into this category include parent/minor child,26 guardian/ward,27 trustee/beneficiary,28 doctor/patient,29 solicitor/client30 and religious adviser/disciple.31 It does not include husband/wife.32 The relationships are those where it is assumed that one person has placed trust and confidence in another, and so is liable to act on that other’s suggestions without seeking independent advice. Other relationships (other than husband/wife) which have these characteristics could be added to the list in the future.

Key Case Allcard v Skinner (1887)33

Facts: The plaintiff had entered a religious order of St Mary at the Cross, and had taken vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. The defendant was the lady superior of the order. Over a period of eight years during which she was a member of the order, the plaintiff gave property to the value of £7,000 to the defendant, most of which was spent on the purposes of the order. The plaintiff left the order, and some six years later sought to recover her property, on the basis that it was given to the order under undue influence.

Held: The property was prima facie recoverable as having been given under the undue influence of membership of the order, which required obedience to the defendant. This was so even though no direct pressure had been placed on the plaintiff. The influence was presumed from the relationship itself. The plaintiff’s action to recover her property did not succeed, however, because of the delay between leaving the order and bringing the action (six years). This lapse of time operated as a bar to recovery.

For Thought

Assuming the time lapse had not occurred in this case, was there anything that the religious order could have done to prevent any gift being recoverable on the basis of undue influence? Doesn’t this make the situation very difficult for religious groups which expect members to undertake obedience to the leaders of the group, if any property received is liable to be returned?

Once there is a relationship from which influence is presumed, in what circumstances can the court conclude that the influence was ‘undue’, under the approach in Etridge?34 This is where the concept which was previously referred to as ‘manifest disadvantage’ becomes relevant. Lord Nicholls referred back to the statement by Lindley LJ in Allcard v Skinner, which was cited by Lord Scarman in developing the concept of ‘manifest disadvantage’ in National Westminster Bank plc v Morgan. Lindley LJ pointed out that a small gift made to a person falling within one of the presumed categories of influence would not be enough in itself to put the transaction aside:35

But if the gift is so large as not to be reasonably accounted for on the ground of friendship, relationship, charity, or other ordinary motives on which ordinary men act, the burden is upon the donee to support the gift.

Following this principle, Lord Nicholls pointed out that it would be absurd if every minor transaction between those in a relationship of presumed influence was also presumed to have been brought about by the exercise of undue influence:36

The law would be out of touch with everyday life if the presumption were to apply to every Christmas or birthday gift by a child to a parent, or to an agreement whereby a client or patient agrees to be responsible for the reasonable fees of his legal or medical advisor … So something more is needed before the law reverses the burden of proof, something which calls for an explanation. When that something more is present, the greater the disadvantage to the vulnerable person, the more cogent must be the explanation before the presumption will be regarded as rebutted.

What is being looked for is a transaction which ‘failing proof to the contrary, is explicable only on the basis that it has been procured by undue influence’.37 In other words, it is not the sort of transaction which the vulnerable person would have entered into in the normal course of events. Lord Hobhouse gives the example of a solicitor buying a client’s property at a significant undervalue.38 The fact that a transaction provides no benefit to the vulnerable person will be evidence supporting the suggestion of undue influence. Thus, once there is a relationship falling within one of the categories of automatically presumed influence, and a transaction which is not of a kind forming one of the normal incidents of such a relationship, there will be an inference of undue influence. It will then be up to the alleged influencer to show that the other party acted without being affected by such influence. The easiest way to do this is likely to be to show that the claimant received independent legal advice before entering into the transaction, though the Privy Council in Attorney General v R did not think that this was necessarily conclusive.39 The adequacy of the advice to protect the influenced party may need to be considered.40 It is certainly not sufficient for the alleged influencer simply to show that there had been no ‘wrongdoing’ on his or her part.41

Even where a relationship does not fall into one of the categories listed in the previous section, it may in fact have developed in a way which indicates that one person is in a ‘dominant’ position over the other. The dominated person will be likely in such a situation to act on the advice, recommendation or orders of the other, without seeking any independent advice, and without properly considering the consequences of his or her actions. The fact that the claimant placed trust and confidence in the defendant in relation to the management of the claimant’s financial affairs will have to be proved by evidence.42 If that is done, then any disadvantageous transaction entered into at the instigation of the dominant party will constitute prima facie evidence that the trust and confidence of the claimant has been abused. The burden of proof will shift to the defendant to produce evidence to counter this inference. If no such evidence is produced, the court will be entitled to conclude that the transaction was in fact brought about by the exercise of undue influence.43 In other words, the issue is the inferences which the court is entitled to draw from the evidence before it, and where the burden of proof lies in relation to that evidence.

Probably the majority of the reported cases that have been regarded as falling under this category of undue influence based on an established relationship of trust and confidence concern a dominant husband and a subservient wife. Similarly, it was held by the Court of Appeal in Leeder v Stevens44 that a relevant relationship had arisen between a married man and a woman with whom he had had what the court called ‘a loving relationship’ over a period of 10 years. A transaction in which she had transferred to him a half share in her house, valued at £70,000, in return for a payment of £5,000 was set aside. This case emphasised the strength of the presumptions. The trial judge had found no evidence of actual coercion at the time of the transaction. The Court of Appeal held that this was irrelevant. Once the relationship was established, and there was a transaction that called for explanation, then it was up to the man to prove that the woman had entered into the transaction with full appreciation of its consequences, and having been properly advised.

Situations of trust do not only arise in the context of sexual or other intimate relationships, as is shown by Attorney General v R,45 where the Privy Council recognised that a relationship between a soldier and his regiment could be such as to give rise to a presumption of influence. Another example is Lloyds Bank Ltd v Bundy.46

Key Case Lloyds Bank Ltd v Bundy (1975)

Facts: Mr Bundy was an elderly farmer. He had provided a guarantee and a charge over his house to support the debts of his son’s business. He was visited by his son and the assistant manager of the bank. The assistant manager told Mr Bundy that the bank could not continue to support the son’s business without further security. Mr Bundy then, without seeking any other advice, increased the guarantee and charge to £11,000. When the bank, in enforcing the charge, subsequently sought possession of the house, Mr Bundy pleaded undue influence.

Held: The court took the view that the existence of long-standing relations between the Bundy family and the bank was important. Although the visit when the charge was increased was the first occasion on which this particular assistant manager had met Mr Bundy, he was, as Sir Eric Sachs put it ‘the last of a relevant chain of those who over the years had earned or inherited’ Mr Bundy’s trust and confidence.47 The charge over the house was obviously risky given the precarious state of the son’s business. There was no evidence that the risks had been properly explained to Mr Bundy by the assistant manager, and therefore Mr Bundy could not have come to an informed judgment on his actions. The charge was set aside on the basis of undue influence.48

Although the period of time over which a relationship has developed is clearly relevant to deciding whether trust and confidence has arisen, it need not be all that long. In Goldsworth v Brickell,49 for example, where the relationship existed between an elderly farmer and his neighbour, it had only been for a few months that the plaintiff had been relying on the defendant. Nevertheless, it was held that the relationship involved sufficient trust and confidence for a disadvantageous transaction to require explanation. In the absence of evidence that the elderly farmer had exercised an independent and informed judgment, the relevant transaction was set aside.

In Credit Lyonnais Bank Nederland NV v Burch,50 it was held that a relationship of trust and confidence could arise between an employer and a junior employee. The employee had acted as babysitter for the employer, and had visited his family at weekends and on holidays abroad. She had agreed to her house being used as collateral for the employer’s business overdraft. The transaction was set aside on the basis of undue influence.

11.5.1 IN FOCUS: CAN THE NATURE OF TRANSACTION ESTABLISH ‘INFLUENCE’?

It was held by Millett LJ in the Court of Appeal in Credit Lyonnais Bank Nederland NV v Burch that a presumption of influence between two people in a relationship which was ‘easily capable of developing into a relationship of trust and confidence’ could be established by the ‘nature of the transaction’ which had been entered into.51 If ‘the transaction is so extravagantly improvident that it is virtually inexplicable on any other basis’, then ‘the inference will be readily drawn’.52 This use of the substance of the transaction as an element in establishing a presumption of influence was unusual. The other pre-Etridge cases in this area operated on the basis of establishing the presumption from the way in which the relationship has developed, before looking at the position in relation to the transaction under consideration. As will be seen below, the disadvantageous nature of the transaction has generally been used as a basis for deciding whether or not relief should be granted once a presumption of influence has been made. Millett LJ’s approach was not specifically followed by the other members of the Court of Appeal, though Swinton Thomas LJ stated in general terms that he agreed with Millett LJ’s reasons for his decision.53 This aspect of Burch was not considered by the House of Lords in Etridge, though the outcome of the case was clearly approved by Lord Nicholls.54 Millett LJ’s analysis, however, would not seem to fit with the Etridge approach. This would look at the relationship between the employer and employee to see if trust and confidence had developed. If it had, then the disadvantageous and risky nature of the transaction which the employee had entered into would raise an inference that it was not undertaken on the basis of informed consent, and that the trust and confidence had been abused. The employer would then need to produce evidence to contradict that inference. If, on the other hand, there was no evidence of a relationship of trust and confidence, no inferences would be drawn from the disadvantageous nature of the transaction, and the employee would need to produce specific evidence of undue influence in order to have it set aside. There is no suggestion in the House of Lords’ speeches in Etridge that the nature of the transaction can be used to establish a relationship of trust and confidence. Thus, if the employee had entered into a disadvantageous transaction simply because she thought it was a good way of currying favour with the boss, perhaps enhancing her prospects of promotion, there would be no scope for a finding of undue influence.

The concept that a transaction must be to the ‘manifest disadvantage’ of the claimant in order for it to be set aside for some types of undue influence derives from the speech of Lord Scarman in National Westminster Bank plc v Morgan.55 Here, Mrs Morgan had agreed to a legal charge over the matrimonial home as part of an attempt to refinance debts which had arisen from her husband’s business. She had been visited at home by the bank manager and had thereupon signed the charge. Lord Scarman, with whom the rest of the House agreed, held that her attempt to have the charge set aside for undue influence failed for two reasons. First, the bank manager’s visit was very short (only about 15 minutes in total), and there was no history of reliance as in Lloyds Bank v Bundy. Second, for the presumption to arise, the transaction had to be to the ‘manifest disadvantage’ of Mrs Morgan. This was not the case here. The charge ‘meant for her the rescue of her home on the terms sought by her: a short term loan at a commercial rate of interest’.56 Thus, although any transaction which puts a person’s home at risk must in one sense be regarded as ‘disadvantageous’, this could not be sufficient on its own to render a contract voidable. If it were, every mortgage agreement would have to be so regarded. In looking for disadvantage, it was necessary to consider the context in which the transaction took place. If it was clear, as it seemed to be in Morgan, that the risks involved were, as far as the claimant was concerned, worth running in order to obtain the potential benefits of the transaction, and there was no other indication of unfairness, then the courts should be quite prepared to enforce it. As has been noted above, some of Lord Scarman’s comments in Morgan were interpreted by the Court of Appeal in BCCI v Aboody57 as applying the requirement of manifest disadvantage to situations of actual, rather than presumed, influence. This interpretation was firmly rejected by the House of Lords in CIBC Mortgages plc v Pitt.58 At the same time, Lord Browne-Wilkinson expressed some concern over the need for the requirement even in cases of presumed undue influence.59 The Court of Appeal in Etridge reaffirmed that it was necessary,60 but in Barclays Bank v Coleman61 suggested that the disadvantage which needed to be shown did not have to be ‘large or even medium-sized’, provided that it was ‘clear and obvious and more than de minimis’.62

Prior to the House of Lords’ decision in Etridge, therefore, the position was that in cases of presumed undue influence, there was a requirement that the transaction should be to the manifest disadvantage of the claimant before it would be set aside. No such requirement existed in relation to actual undue influence. What exactly was meant by ‘manifest disadvantage’ was, however, becoming increasingly obscure, with obiter statements in the House of Lords and in the Court of Appeal suggesting that it might not be necessary at all. The decision of the House of Lords in Etridge has not changed the position in relation to actual undue influence. If such influence is established, then the court should set the agreement aside irrespective of whether it was to the actual or potential benefit of the claimant. This must be based on the policy view that it is unacceptable for the courts to enforce any transaction where it has been demonstrated that the actions of one party have led to it being entered into without the free, informed consent of the other. The approach is similar to that taken in relation to a totally innocent misrepresentation, where a party is allowed to rescind without showing that the misrepresentation has caused any loss.63

In relation to situations where there is presumed influence, either from a recognised ‘special relationship’, or because a particular relationship of trust and confidence has been established, then, as indicated above,64 the nature of the transaction becomes relevant in considering whether the court may draw any inferences of undue influence from that relationship. The phrase ‘manifest disadvantage’ should not be used,65 and it is certainly not the case that the claimant has to prove such disadvantage to establish that there was undue influence in such a case. The relevance of the nature of the transaction is evidential.66 If it is shown to be of a kind which calls for explanation (for example, because it benefits the defendant without providing any comparable benefit for the claimant), then this will impose a burden on the defendant to show that it was not in fact obtained by undue influence, that is, an abuse of the relationship of trust and confidence.

Lord Nicholls and Lord Scott both indicated that they did not regard the fact that a wife acts as surety for her husband’s business debts as in itself being sufficient to give rise to an inference that influence has been abused. As Lord Nicholls put it:67

I do not think that, in the ordinary course, a guarantee of the character I have mentioned [that is, the guarantee by a wife of her husband’s business debts] is to be regarded as a transaction which, failing proof to the contrary, is explicable only on the basis that it has been procured by the exercise of undue influence by the husband. Wives frequently enter into such transactions. There are good and sufficient reasons why they are willing to do so,68 despite the risks involved for them and their families … They may be anxious, perhaps exceedingly so. But this is a far cry from saying that such transactions as a class are to be regarded as prima facie evidence of the exercise of undue influence by husbands.

I have emphasised the phrase ‘in the ordinary course’. There will be cases where a wife’s signature of a guarantee or a charge of her share in the matrimonial home does call for explanation.69 Nothing I have said is directed at such a case.

Lord Hobhouse seems prepared to regard the fact that a wife acts as surety for her husband’s business debts as more readily raising an inference calling for an explanation by the husband – for example, that he has taken account of her interests, dealt fairly with her, and made sure that she entered into the obligation freely and with knowledge of the true facts.70 It is likely, however, that the approach taken by Lord Nicholls and Lord Scott, with whom Lord Bingham concurred, will be the one that is followed.

The conclusion of all this is that ‘manifest disadvantage’ is no longer a part of the law relating to undue influence; the nature of the transaction may, however, in cases where influence is presumed, provide evidence which will put the burden on the defendant to show that the influence was not abused.

The current law is based on the House of Lords’ decision in Royal Bank of Scotland plc v Etridge (No 2), and all earlier case law must be considered in the light of this.