Trust Formation: The Three Certainties

Chapter 5

Trust Formation: The Three Certainties

Chapter Contents

Chapter 4 considered the first two main requirements to form an express trust: that the settlor must have mental and legal capacity and that, for certain types of property, formalities must be fulfilled. This chapter moves on to consider the next requirement: that the trust must be certain.The requirement of certainty can itself be split into three parts: intention, subject matter and object.

As You Read

In this chapter, the focus is on the three certainties, all of which are required in order for the trust to be properly declared. When reading this chapter, pay particular attention to:

certainty of intention — it must be clear that the settlor truly wanted to establish a trust. The case law on this point focuses on settlors using vague words and, through their use, not evidencing a true intention to set up a trust;

certainty of intention — it must be clear that the settlor truly wanted to establish a trust. The case law on this point focuses on settlors using vague words and, through their use, not evidencing a true intention to set up a trust;

certainty of subject matter — this focuses on the actual property that the settlor wishes to leave on trust. Obviously, in order for the trustee to administer the trust properly, it must be clear both what property is being left on trust and also, if there is more than one beneficiary, the shares in which those beneficiaries are to enjoy the trust property; and

certainty of subject matter — this focuses on the actual property that the settlor wishes to leave on trust. Obviously, in order for the trustee to administer the trust properly, it must be clear both what property is being left on trust and also, if there is more than one beneficiary, the shares in which those beneficiaries are to enjoy the trust property; and

certainty of object — arguably, this is the most difficult certainty for students to grasp. Read this section of the chapter particularly carefully, focusing on the difficulties settlors have met when trying to be clear over who is to benefit in a discretionary trust.

certainty of object — arguably, this is the most difficult certainty for students to grasp. Read this section of the chapter particularly carefully, focusing on the difficulties settlors have met when trying to be clear over who is to benefit in a discretionary trust.

Formation of an Express Trust

Central to how any type of trust is formed is an understanding of how an express private (as opposed to charitable) trust is created. Implied trusts, as has been seen,1 exist to fill in gaps and, on a number of occasions, have been recognised because settlors have failed to create an express trust properly.2

By way of a brief reminder, to be created properly, an express private trust must be both correctly declared and constituted by the settlor. For the settlor to declare a trust correctly, he must ensure that the following issues have been dealt with properly:

[a] the trust is certain, or clear, in terms of:

[i]the settlor evidencing a clear intention to set up the trust;

[ii] the subject matter (or property) which is to be placed on trust can be said to be clear and the proportions in which the beneficiaries are to enjoy the property are equally clear; and

[iii] who is to enjoy the property;

[b] the settlor must adhere to any formality requirements in establishing the trust. These have been considered in detail in Chapter 4 . As you have seen, whether there are any formal requirements to set up a trust depends on what the property being left on trust is. For instance, if the trust property is shares, they must be transferred to the trustee using a stock transfer form.3 If the property being left on trust is land, then the effect of s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 means that the settlor must evidence his declaration of trust by using a written document, which he signs;

[c] the settlor must adhere to the beneficiary principle. Again, this is a topic which should be considered in its own right,4 but the basic concept is that a trust must have someone who can enjoy the benefit of it. As will be seen,5 English law generally dislikes trusts which benefit no clearly defined beneficiary; and

[d] the settlor must ensure that the trust he creates does not last forever. This is usually expressed by saying that the settlor must comply with the rules against perpetuity.6 The fundamental principle behind the rules is to ensure that trusts do not last forever, thus tying up property in trusts instead of it being able to be used freely in the economy.

Together with ensuring that the trust is properly declared, the settlor must also ensure that the trust is constituted. This entails the settlor properly transferring the property he intends to settle on trust to the trustee, so that the trustee can then hold it on trust for the beneficiary. Constitution of a trust is considered in detail in Chapter 7.

The Three Certainties

The basics…

The three certainties comprise:

certainty of object;

certainty of object;

certainty of subject matter; and

certainty of subject matter; and

certainty of intention.

certainty of intention.

Key Learning Point

All three certainties are as vital as each other in creating an express trust. It is not possible to choose a supermarket ‘any 3 for 2’ style offer: all three certainties are needed for the trust to be validly formed.

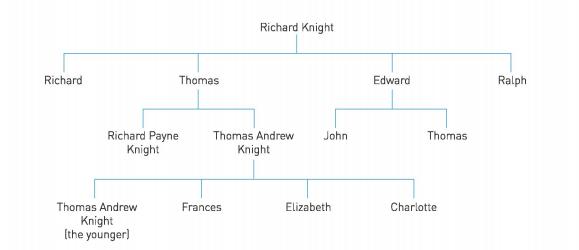

The three certainties were explained by Lord Langdale MR in Knight v Knight.7 A family tree setting out the relationships in this family is shown below at Figure 5.1.

The case concerned the will of Richard Payne Knight. He had inherited land from his grandfather and his grandfather’s wish in his will was that the land should pass down to his male heirs. Richard left the land in his will to his brother, Thomas Andrew Knight. At the end of his will, however, Richard stated the following words, in which he asked for the lands to continue to be left to the male descendants of his grandfather, Richard Knight:

I trust to the liberality of my successors … to their justice in continuing the estates in the male succession, according to the will of the founder of the family, my above-named grandfather, Richard Knight.

Thomas Andrew duly inherited the land from Richard upon Richard’s death. Thomas Andrew himself had a son, but his son predeceased him. In his will, Thomas explained that he wanted to give effect to his own son’s wishes by leaving the lands to his son’s three sisters, Frances, Elizabeth and Charlotte. Such a direction brought Thomas Andrew into conflict with other male members of the family, who were descendants of Richard’s grandfather. The claimant in the case was John, one of those other male members of the family. John’s case was that the lands could not be left by Thomas Andrew to his daughters. Instead, John argued that Richard Payne Knight had created a trust of the lands in his will through the use of the words quoted above and consequently, he should enjoy the lands as a beneficiary under the trust. The argu-ment to the contrary was that no trust was created by Richard Payne Knight by those words. A trust could only be created by a settlor imposing a clear obligation on the trustee to hold property for a beneficiary’s benefit and the words Richard used fell far short of imposing an obligation on any trustee.

In giving the judgment of the Court of Chancery, Lord Langdale MR stated that where property was given to another person and the recipient had been ‘recommended, entreated or wished’ by the giver to hold the property for a third party, then a trust would be created. Crucially, however, he said that this was subject to three requirements:

if the words are so used, that upon the whole, they ought to be construed as imperative;8

if the subject of the recommendation or wish be certain; and

if the objects or persons intended to have the benefit of the recommendation or wish be also certain.9

The point was that not all instructions by one person to another to hold land for the benefit of a third party would create a trust. The instructions had to fulfil the requirements of certainty. Certainty could be broken down into the three parts that the Master of the Rolls set out: certainty of the words that the settlor used, certainty of the subject matter of the trust and lastly, certainty of the person who it was intended should benefit from the trust. All three key areas of a trust had to be certain before the trust would be recognised.

On the facts of the case, it was held that Richard Payne Knight had not created a trust:

[a]he had not used words which showed a clear intention to create a trust. Instead, he had left it to the successors in his family to do ‘justice’ in continuing to leave the property to the male descendants of his grandfather. Such wording suggested that the recipients had a discretion over whether or not to continue the succession to future male heirs;

[b]by describing the property left in his will as ‘the estates’, Richard Payne Knight had not clearly shown which property that description related to. It was impossible on the facts to determine precisely which property Richard meant and consequently, the subject matter of the alleged trust was not certain; and

[c]whilst Richard Payne Knight had described whom he wished to benefit, this was not enough since he had not set out their beneficial entitlements in terms of precisely what equitable interest he wanted them to have. He had not, for example, clearly set out that each beneficiary should have a life interest in property left to them.

Why does English law insist on the need for the three certainties?

The court must be able to recognise a trust as intended by a settlor and cannot write a trust for him. The court uses the three certainties as a means of ascertaining the terms of the trust: whether, crucially, the settlor actually intended to set up a trust, what the subject matter (or property) of the trust is and who the settlor intended should benefit from the trust. The function of the court is simply to recognise the trust that the settlor created, not to invent a trust for the settlor’s benefit.

Additionally, the three certainties help to ensure that a trustee can properly manage a trust. The trustee must be sure that a trust has been created, be clear what property is expected to be held on trust and must be confident that he is managing the trust on behalf of beneficiaries that are the people whom the settlor intended.

It is this requirement of certainty, or clarity, that ensures that not only the court but also all of those involved in the trust — the settlor, the trustee and the beneficiary — can be sure of the fundamental terms of a trust.

Certainty of Intention

This certainty considers whether the settlor showed sufficient intention to set up a trust. As such, it focuses on the words used by the settlor. Indeed, as we have seen in Knight v Knight,10 Lord Langdale MR specifically mentioned that the settlor’s words had to be ‘construed as imperative’.

The key to understanding this certainty is that the settlor must express an intention, when viewed in the context of the words he uses, to subject another person to a binding obligation to hold property for the benefit of a third party.

No special words have to be used to display intention

Ultimately, it is not necessary for every settlor to use a particular set of ‘special’ words to satisfy this certainty. Remember the equitable maxim that equity looks to the substance and not the form of actions or words used. This has the consequence here that equity will look to see if the words used contain an intention by the settlor to make sure that the recipient of the property has no option but to hold the property on trust for the benefit of a third party. It is only if the recipient is under an obligation to hold the property for someone else’s benefit that this certainty will be met. Equity looks to find the settlor’s intention by considering the words the settlor used in establishing the alleged trust. Due to equity focusing on the words used, this certainty is sometimes referred to as the ‘certainty of words’.

If the settlor uses the word ‘trust’ then that may be a good indication that he intended to create a trust, but it all depends on the context in which that particular word is used. As we have seen, in Knight v Knight itself, the settlor used the word ‘trust’ but, in fact, no trust was deemed by the court to have been intended to have been created. The case is a good illustration of the maxim11 of equity looking to the substance and not the form of the precise word(s) used. Even though the settlor had used the word ‘trust’, when viewed in the context of the other words used — that the recipients of the property could leave it to their own ‘justice’ to decide who would take the lands after themselves — it was not clear that the settlor had intended to impose a binding obligation on the recipient of the property.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Many legal precedents (templates) used by lawyers for creating express trusts do, of course, contain the word ‘trust’ in them. It is, therefore, considered to be good practice to mention the word ‘trust’ when a settlor sets up an express trust because that very word gives a good indication of the settlor’s intentions at the time the arrangement is set up.

Settlors have not always used words which show a clear intention to subject the recipient of the property to a binding obligation to hold that property on trust for a beneficiary. Where the courts have not been able to deduce a clear and certain intention by a settlor to impose such a binding obligation on another, then no trust has been held to have been created.

The leading case in this area remains Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry.12

The facts of the case concerned a conveyancing dispute over a piece of land in Notting Hill, London. A lease had been granted in 1819 giving the tenant the right to purchase the freehold interest in the land. The tenant — Charles Adams — duly bought the freehold in July 1877. In the meantime, the original freehold owner (George Smith) had made a will, in which he left everything to the ‘absolute use of my dear wife’:

in full confidence that she will do what is right as to the disposal thereof between my children, either in her lifetime or by will after her decease.

Charles Adams tried to sell the land to the Vestry of the parish of St Mary Abbotts, Kensington. The Vestry was concerned that he had no legal right to sell the land, as the Vestry feared that it had been subjected to a trust by George Smith in his will, in the terms of the words set out above.

The Court of Appeal focused on the need to ascertain the intentions of George Smith. A trust would only be found if it could clearly be shown that he had intended to create a trust by considering the words used.

The court held that no trust had been intended by the words used, when looked at in their entirety. Instead, George Smith had intended to give the property to his wife entirely. By being confident that she would use the property for the benefit of their children, he may have placed her under a moral obligation to make such use of the property, but he had never intended to put her under a binding legal obligation to do so. As she had not been placed under a legal obligation, there could be no trust of the land in favour of her children. As the absolute owner, she was free to sell the land to whomever she chose. She had chosen to sell it to Charles Adams and, in turn, he was entirely free to sell it to the Vestry.

‘Precatory’ (or ‘begging’) words do not create a trust

In terms of the historical development of the law of trusts, Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry continued the turning point when construing a settlor’s intention. The case confirmed the move away from earlier cases in which the court placed emphasis on the precise word(s) used by the settlor.

Previously, the Court of Chancery had recognised a trust, even though a certain type of ‘precatory’ word had been used. These gave rise to so-called ‘precatory trusts’. 13 Precatory words were merely words which begged, asked, or requested recipients to look after property on behalf of a third party. The Court of Chancery had wanted to recognise such trusts as, if no trust was found, the executors of the deceased’s will would have been personally entitled to the deceased’s property!

The change in judicial thought as to the types of trust that ought to be recognised occurred in Lambe v Eames.14

John Lambe left his property in his will to his widow ‘to be at her disposal in any way she may think best for the benefit of herself and family’. One of John’s sons had an illegitimate son, Henry Lambe. The widow left the property on trust for her daughter, Elizabeth Eames, but with an annual sum for Henry’s benefit. Elizabeth failed to pay Henry his allowance, so Henry brought an action. Elizabeth’s defence was that there was no trust at all because all the widow could ever do was leave the property to her family, according to the terms of John’s will. Her argument was that the widow had acted outside of her power by leaving an allowance to Henry as, being illegitimate, he was not a family member.

The case shows the court construing the testator’s intention from his will. John had not imposed an obligation on his widow to deal with his property in a particular manner and consequently, no trust could be found.

The Court of Appeal in Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry continued this development and preferred not to look at individual words used on their own but to place them in the context in which they appeared in the document. Only then could the settlor’s true intention be ascertained. As Cotton LJ said:

[W]e must not … rely upon the mere use of any particular words, but, considering all the words which are used, we have to see what is their true effect, and what was the intention of the testator as expressed in his will.15

Looking at the words in the context of their use enabled the court to obtain a more rounded picture of what the settlor really intended. Such a rounded picture was likely to be far more reflective of the settlor’s true intentions as opposed to taking a word out of its context and deciding its meaning in the abstract.

This development against the use of precatory words was reaffirmed in another decision of the Court of Appeal just four years later — Re Diggles.16 In this case, Mary Ann Diggles made a will in which she left all of her property to her daughter but said that she had a ‘desire’ that an annual sum of £25 should be paid by her executors to her companion, Anne Gregory, for the rest of Anne’s life. Ms Diggles died and, for eleven years after her death, £25 was paid each year to Anne. The payments then stopped. Anne brought an action against the executors. The basis of her action was that the executors were under a binding obligation to pay her the annual sum. Anne argued that she was the beneficiary of a life interest under a trust which Ms Diggles had established and the executors were the trustees.

Cotton LJ reminded the court that the task was to construe the trust as a whole to ascertain Ms Diggles’ true intention. The task was not just to focus on particular words. Ms Diggles’ true intention was to give all of her property to her daughter. She had merely added a wish that her daughter should provide for Anne. As Bowen LJ explained,17 imposing a mere ‘desire’ gave the daughter a choice over whether Anne should receive the annual sum or not. Such a desire was entirely different from imposing a binding obligation on her daughter. And, of course, a trust could only have been said to have been created if a binding obligation was imposed.

Fry LJ pointed out the inconvenient consequences if the court had held that there was a trust. Ms Diggles had not provided a separate sum of money for the annual payment to Anne. Consequently, the daughter would have had to fund the payment from the property left to her, all of which would have been held under a trust in favour of Anne for life, remainder to the daughter. The daughter would have had to sell some of the trust property to fund the annual payment. This made no sense in terms of Ms Diggles merely expressing a desire, or wish, for Anne to receive the money. Such precatory words would have to be construed in the context of the document as a whole as to whether a trust would be created. On the facts here, there was no intention by Ms Diggles to subject her daughter to an obligation.

The court is always trying to ascertain if the settlor expressed clear enough wishes to amount to an obligation to place the recipient of the legal estate in the property under an obligation to hold the property on trust for a beneficiary. There are situations where what initially appear to be precatory words can amount to a trust because, construed in the context of the document as a whole, it can be said that the settlor intended to subject a recipient to binding trustee obligations. Such a situation arose in Comiskey v Bowring-Hanbury.18

The case concerned the will of a Member of Parliament, Mr Hanbury, in which he left all of his property (which consisted of a number of valuable collieries) to his wife, Ellen, ‘in full confidence that she will make such use of it as I should have made myself’ and that, when Ellen died, she was to leave the property to whichever of Mr Hanbury’s nieces she chose. Crucially, the will provided that if Ellen made no choice, the property was to be split equally between the nieces when Ellen died. Following Mr Hanbury’s death, Ellen brought an action before the court, in which she wanted to know whether her husband had created a trust in his will, or whether the words used showed insufficient certainty of intention to bind her to an obligation to give the property to his nieces when she died. If the latter was the case, then there would be no trust and Ellen would have taken the property for herself absolutely.

Both the trial judge and the Court of Appeal held that Mr Hanbury’s words did not subject his widow to an obligation to hold the property on trust for the nieces. As such, she took the property absolutely. The nieces appealed to the House of Lords.

The House of Lords, by a majority, reversed the Court of Appeal’s decision and held that the words were sufficient to subject Ellen to a binding obligation.

Lord James reminded the House19 that its ‘only duty’ was to ascertain the testator’s intention and that could only be ascertained from the words of the will. The House had to give the ‘natural and ordinary meaning’ to the words used by the testator.20 The words had to be considered overall, without special focus on any particular words on their own. As Lord Davey explained:

The words which have been so much commented upon, ‘in full confidence’, are, in my opinion, neutral… . They are words which may or may not create a trust, and whether they do so or not must be determined by the context of the particular will in which you find them.21

In this context, the words ‘in full confidence’ did merely express a hope, or desire, by Mr Hanbury that Ellen would use it as he would have done and leave it to his nieces when she died. If she did not dispose of the property by choosing which of his nieces were to receive it, then the final words of this part of the will would be crucial:

I hereby direct that all my … property … shall at her death be equally divided among the surviving said nieces.

It was not possible to separate ‘in full confidence’ from those final words of that part of the will. They had to be read together. When read together, they meant that Ellen could use the property for her lifetime only and that, on her death, the property had to go to Mr Hanbury’s nieces. She could choose which niece(s) was to receive it, but if she made no choice, Mr Hanbury’s instructions were clear: the property had to be split equally between those nieces still living. Ellen’s only real choice in this arrangement was which niece might get the property on her death. The words therefore imposed an obligation on Ellen to look after the property during her lifetime and, on her death, to pass it on to the nieces. Due to an obligation being imposed, a trust had been created of the property. Ellen was to have a life interest and the nieces, either chosen by Ellen or all of them equally if she made no choice, were to have the remainder interest.

If a settlor chooses to use exactly the same words which have been given meaning in a decided case already, however, the court will assume that the settlor wanted those words to be given the same meaning in his particular case. The settlor must have had a reason for using precise words which had previously been adjudicated upon. Whilst the court is trying to ascertain the settlor’s intention, it will hold that, by using particular words that had already been held to have a precise meaning, the settlor intended to have that meaning applied to his settlement. This principle can be shown in Re Steele’s Will Trusts.22

The case involved a diamond necklace belonging to Mrs Adelaide Steele. She wrote her will, in which she left the necklace to her son and then to his eldest son and, in turn, to his eldest son and so on as far as she was legally permitted to do. The relevant provision of the will ended with the words, ‘and I request my said son to do all in his power by his will or otherwise to give effect to this my wish’.

The trustees of Mrs Steele’s will brought an action to the High Court to determine if Mrs Steele had created a trust by imposing an obligation on her son to pass the necklace down the family line. Their query was whether those final words used by Mrs Steele were precatory in nature since she merely requested her son to do everything he could to give effect to her ‘wish’. If no obligation had been imposed upon him by those words, there could be no intention by Mrs Steele to subject her son to a trust, so he would take the necklace as an absolute gift.

Wynn-Parry J noted that the words used by Mrs Steele in her will were the same as had been used by a previous testatrix in Shelley v Shelley23 and the court had held in that case that a valid trust had been created. The difficulty was that Shelley v Shelley was a case which pre-dated Re Adams and the KensingtonVestry and was decided at a time when courts of equity were, of course, more inclined to declare trusts, even though they involved precatory words in their creation.

Yet Wynn-Parry J was able to reconcile the decision in Shelley v Shelley with the ‘new’ direction the courts had taken since Re Adams and the KensingtonVestry. He said that he followed the decision in Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry as he recognised that his task was to discover Mrs Steele’s true intentions by looking at all of the words she used in her will in their context. Her will had been professionally prepared and no doubt the lawyer who drew up the will was familiar with the decision in Shelley v Shelley. By adopting the same words, Wynn-Parry J held that Mrs Steele’s true intention was for her property to be subjected to the same result as the property left by will in Shelley v Shelley. In this manner, Wynn-Parry J was still giving pre-eminence to finding Mrs Steele’s intention.

It is submitted that this decision is not without its difficulties. Shelley v Shelley was a decision in which certainty of intention was not given as much prominence as it was later to receive after the decision in Re Adams and the KensingtonVestry. The judge in Shelley v Shelley, Sir W Page Wood V-C, gave prominence not so much on ascertaining the testatrix’s intentions as instead focusing on the fact that the objects of the trust were certain. Whilst the judge considered the testatrix’s intention ‘clear and precise’,24 he seems to have done so on the basis that the court should recognise that a trust exists as the beneficiaries could be easily ascertained. Much weight was placed on the beneficiaries of the trust being certain. As the beneficiaries were certain, that had to mean that there was a trust. The decision in Re Adams and the Kensington Vestry later placed more weight on ascertaining the settlor’s true intentions independently of whether the beneficiaries of the trust were certain. It gave ascertaining the settlor’s intentions more prominence and brought the task of ascertaining those intentions up to the same level of importance as finding out if the beneficiaries were certain.

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

How close do you think the words used in a present will have to be to those used in a will in a previously reported decision? They were exactly the same in Re Steele’s Will Trusts but do you think that they have to be? Would it be sufficient to use similar words? Would similar words clearly show an intention to have the same consequence as the words used in the earLier decision?

By relying heavily on Shelley v Shelley, arguably the decision in Re Steele’s Will Trusts does not take into account the spirit of the decision in Re Adams and the KensingtonVestry in trying to ascertain this particular testatrix’s intentions. Instead, it relies on this testatrix having the same intention as the testatrix in Shelley v Shelley, but the intention of the testatrix in that case was barely mentioned and her intention to create a trust was simply assumed to exist. Notwithstanding this, the principle in Re Steele’s Will Trusts remains good law.

Actions can speak as loud as words

If the facts of the individual case support it, it will not just be the settlor’s words, but also their actions in support of their words, that the court will keep in mind in ascertaining whether the settlor expressed sufficient certainty of intention to create a trust.

This has been shown in Chapter 2 25 in the discussion of Paul v Constance26 and Jones v Loci.27

In Paul v Constance, a settlor paid several sums of money into a joint bank account. The question for the Court of Appeal was whether the settlor had declared a trust of those sums. It was held that he had created a trust through a combination of his words and his actions. He often told the claimant that ‘[t]his money is as much yours as mine’. His actions involved opening a bank account which was only in his sole name because of the embarrassment he and the claimant would have felt in asking the bank to open an account in their joint names when they were living together whilst not being married. The actions of opening the bank account and paying in joint sums of money could be seen as bolstering an intention to create a trust, albeit that Scarman LJ could not be sure when that intention to create a trust came into existence.

The case can be contrasted with Jones v Lock. There the settlor handed over a cheque to his baby son with the words ‘I give this to baby … .’ After rescuing the cheque from the child when it was about to be torn up, the settlor placed the cheque in his safe. The court held that the settlor had not declared a trust of the money. His words and actions did not indicate he had ever intended to do so. The court found that the settlor had no intention to burden himself with the responsibilities of trusteeship. The settlor’s action of placing the cheque in the safe was neutral. It did not bolster an oral intention to declare a trust.

The settlor’s actions can be as relevant as their words in determining whether a trust has been created. The court will look at all the circumstances surrounding the creation of the trust to determine whether the settlor has expressed sufficient intention to declare it.

Certainty of intention in trusts involving businesses

What has been discussed so far with certainty of intention has involved considering the matter in relation to traditional, family trust cases. The requirement that the settlor must clearly intend to create a trust applies to all types of trust, however, not just those involving families. In cases involving businesses, it can be more difficult to pinpoint that a settlor intended to establish a trust since the trust is not typically created by the settlor at such a momentous time as when an individual testator writes his will.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Think about why it is important to establish if a trust is created in a business setting. This issue can be vital if a business has monetary difficulties.

When a company becomes insolvent, the property that the business owns passes to the liquidator. The liquidator’s task is to settle the business’s debts and to pay the creditors (the people to whom the creditor owes money) the amounts that they are owed from the remaining money. Usually there is insufficient money remaining to pay each creditor in full. The reason the company has become insolvent is because it does not have sufficient money to pay its debts.

A trust is an attractive proposition from a creditor’s point of view because, if successful, it ring-fences property in favour of the creditor. If the successful creditor can establish a trust in their favour, he will own the equitable interest in the property and will be entitled to have it returned to him. That means that the liquidator cannot use that property to pay creditors in general.

The difficulty of pinpointing certainty of intention in a business context was highlighted by Megarry J in Re Kayford Ltd (In Liquidation).28

The case concerned a mail-order company that specialised in soft furnishings. It received orders from members of the public, who would either pay in full, or provide a deposit for the goods when they placed their orders. Kayford Ltd depended on another company to supply it with the soft furnishings. That supplier became insolvent. Fearing that Kayford Ltd would also get into financial difficulties, the managing director of the company sought advice from its accountants over how to keep its customers’ prepayments safe and secure in the event that it too became insolvent.

Kayford Ltd then went into liquidation. The company’s liquidator argued that the money in the separate account — which totalled nearly £38,000 — belonged to the company and so, on liquidation, to the company’s creditors. Against that stood the customers, who argued that a trust had been created by the company of the money in the account in their favour.

Megarry J held that a trust had been created. As far as certainty of intention was concerned, he acknowledged the issue was whether ‘in substance a sufficient intention to create a trust has been manifested’.29 But unlike the cases involving individuals, Megarry J did not have the advantage of being able to construe the precise words that the company had used in the context of a larger document. Instead, he had to construe the company’s actions as well as the few words it had used in its intended description of the account.

He found that the entire purpose of the company putting the customers’ prepayments into a separate bank account was to ensure that the equitable interest in those prepayments remained with the customers and did not transfer to the company. As he put it, ‘a trust is the obvious means of achieving this’.30 The company had successfully showed an intention to create a trust by its words and actions. It had:

[a]considered very carefully how to protect its customers’ prepayments in the event of its insolvency;

[a] instructed its bank to use a separate account (which Megarry J described as ‘useful (though by no means conclusive))’;31 and

[a] asked that the name of that account reflect that the company was a trustee of the money for the customers.

In the context of a business relationship, therefore, not only the words but also the actions of the settlor (business) may be used to ascertain whether there is an intention manifested to create a trust.

The decision of Megarry J appears to have been influenced by reasons of policy. He made it clear at the end of his judgment that he supported the actions of a company, such as Kayford Ltd, which tried to act in its customers’ best interests by endeavouring to keep their money safe in a separate bank account. He seems to have had sympathy with the individual customers who had made the prepayments to Kayford Ltd and wished to assist those customers. He made it clear that his decision only applied where the court was dealing with individuals who had made such prepayments saying that ‘different considerations’ may apply in relation to businesses who had made such prepayments to companies who later became insolvent. He hinted that the court may not so readily hold that a trust had been established in such a case.

Such a case arose, however, in Re Lewis’s of Leicester Ltd.32