THEFT

AIMS AND OBIECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the basic origins and character of theft

Understand the basic origins and character of theft

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of theft

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of theft

Be able to analyse critically the concept of appropriation in the definition of theft

Be able to analyse critically the concept of appropriation in the definition of theft

Understand the meaning of ‘property’ in the definition of theft and when that property is regarded as belonging to another

Understand the meaning of ‘property’ in the definition of theft and when that property is regarded as belonging to another

Understand the concept of dishonesty in the law of theft

Understand the concept of dishonesty in the law of theft

Understand the importance of an intention to permanently deprive in the offence of theft

Understand the importance of an intention to permanently deprive in the offence of theft

Be able to analyse critically all the elements of the theft

Be able to analyse critically all the elements of the theft

Be able to apply the law to factual situations to determine whether an offence of theft has been committed

Be able to apply the law to factual situations to determine whether an offence of theft has been committed

13.1 Background

The law relating to theft, robbery, burglary and other connected offences against property (see Chapters 14 and 15) is contained in three Acts:

Theft Act 1968

Theft Act 1968

Theft Act 1978 (s 3 only)

Theft Act 1978 (s 3 only)

Fraud Act 2006

Fraud Act 2006

The Theft Act 1968 was an attempt to write a new and simple code for the law of theft and related offences. It made sweeping and fundamental changes to the law that had developed prior to 1968. The Act was based on the Eighth Report of the Criminal Law Revision Committee, Theft and Related Offences, Cmnd 2977 (1966). Previous Acts were repealed and the 1968 Act was meant to provide a complete code of the law in this area.

The Act is intended to be

JUDGMENT

‘expressed in simple language, as used and understood by ordinary literate men and women. It avoids as far as possible those terms of art which have acquired a special meaning understood only by lawyers in which many of the penal enactments were couched.’

Lord Diplock in Treacy v DPP (1971) 1 All ER 110

Despite this, the wording of the Theft Act 1968 has led to a number of cases going to the appeal courts. The decisions in some of these cases are not always easy to understand. In particular there have been complex decisions on the meaning of the word ‘appropriates’. Another problem is that, as the wording uses ordinary English, the precise meaning is often left to the jury to decide. This can lead to inconsistency in decisions. As Professor Sir John Smith pointed out:

QUOTATION

‘Even such ordinary words in the Theft Act as “dishonesty”, “force”, “building” etc. may involve definitional problems on which a jury require guidance if like is to be treated as like.’

D Ormerod, Smith and Hogan Criminal Law (13th edn, Butterworths, 2011), p 779

Amendments to the Theft Act 1968

It soon became apparent that the law was defective in the area of obtaining by deception and, following the Thirteenth Report by the Criminal Law Revision Committee, Cmnd 6733 (1977), the Theft Act 1978 was passed. This repealed part of s 16 of the 1968 Act and instead created four new offences. The 1978 Act also added another offence, of making off without payment, to fill a gap in the law.

Despite this amendment, it was held in the case of Freddy (1996) 3 All ER 481 that the law still did not cover certain deception frauds in obtaining mortgages and money transfers. The Law Commission was asked to research this area of law, and following their report Offences of Dishonesty: Money Transfers, Law Com No 243, the Theft (Amendment) Act 1996 was passed to fill these gaps. This Act made amend-ments to both the Theft Act 1968 and the Theft Act 1978. However, the offences of deception were still not satisfactory and all deception offences were repealed and replaced by offences under the Fraud Act 2006.

13.1.1 Theft

Theft is defined in s 1 of the Theft Act 1968 which states that:

SECTION

‘1 A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it.’

The Act then goes on in the next five sections to give some help with the meaning of the words or phrases in the definition. This is done in the order that the words or phrases appear in the definition, making it easy to remember the section numbers. They are:

s 2 — ‘dishonestly’

s 2 — ‘dishonestly’

s 3 — ‘appropriates’

s 3 — ‘appropriates’

s 4 — ‘property’

s 4 — ‘property’

s 5 — ‘belonging to another’

s 5 — ‘belonging to another’

s 6 — ‘with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it’

s 6 — ‘with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it’

tutor tip

Remember that the offence is in s 1. A person charged with theft is always charged with stealing ‘contrary to section 1 of the Theft Act 1968’. Sections 2 to 6 are definition sections explaining s 1. They do not themselves create any offence.

13.1.2 The elements of theft

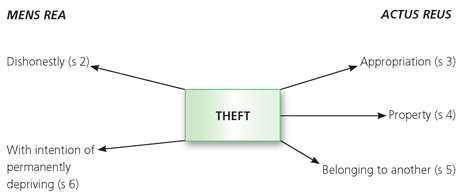

The actus reus of theft is made up of the three elements in the phrase ‘appropriates property belonging to another’. So to prove the actus reus it has to be shown that there was appropriation by the defendant of something which is property within the definition of the Act and which, at the time of the appropriation, belonged to another. All these seem straightforward words, but the effect of the definitions in the Act together with case decisions means that there can be some surprises. For example, although the wording ‘belonging to another’ seems very clear, it is possible for a defendant to be found guilty of stealing his own property. (See section 13.4.1.)

There are two elements which must be proved for the mens rea of theft. These are that the appropriation of the property must be done ‘dishonestly’, and there must be the intention of permanently depriving the other person of it.

We will now go on to consider each of the elements of theft in depth.

Figure 13.1 The elements of theft

13.2 Appropriation

The more obvious situations of theft involve a physical taking, for example a pickpocket taking a wallet from someone’s pocket. But appropriation is much wider than this.

Section 3(1) states that:

SECTION

‘3(1) Any assumption by a person of the rights of an owner amounts to an appropriation, and this includes, where he has come by the property (innocently or not) without stealing it, any later assumption of a right to it by keeping or dealing with it as owner.’

13.2.1 Assumption of the rights of an owner

The first part to be considered is the statement that ‘any assumption by a person of the rights of an owner amounts to appropriation’. The rights of the owner include selling the property or destroying it as well such things as possessing it, consuming it, using it, lending it or hiring it out.

In Pitham v Hehl (1977) Crim LR 285, CA, D had sold furniture belonging to another person. This was held to be an appropriation. The offer to sell was an assumption of the rights of an owner and the appropriation took place at that point. It did not matter whether the furniture was removed from the house or not. Even if the owner was never deprived of the property, the defendant had still appropriated it by assuming the rights of the owner to offer the furniture for sale.

In Corcoran v Anderton (1980) Cr App Rep 104, two youths tried to pull a woman’s handbag from her grasp, causing it to fall to the floor. The seizing of the handbag was enough for an appropriation (the youths were found guilty of robbery which has to have a theft as one of its elements), even though they did not take the bag away.

The wording in s 3(1) is ‘any assumption by a person of the rights of an owner’. One question which the courts have had to deal with is whether the assumption has to be of all of the rights or whether it can just be of any of the rights. This was consid-ered in Morris (1983) 3 All ER 288.

CASE EXAMPLE

Morris (1983) 3 All ER 288

D had switched the price labels of two items on the shelf in a supermarket. He had then put one of the items, which now had a lower price on it, into a basket provided by the store for shoppers and taken the item to the check-out, but had not gone through the check-out when he was arrested. He was convicted of theft. The House of Lords upheld his conviction on the basis that D had appropriated the items when he switched the labels.

Lord Roskill in the House of Lords stated that:

JUDGMENT

‘It is enough for the prosecution if they have proved … the assumption of any of the rights of the owner of the goods in question.’

So there does not have to be an assumption of all the rights. This is a sensible decision since in many cases the defendant will not have assumed all of the rights. Quite often only one right will have been assumed, usually the right of possession.

Later assumption of a right

Section 3(1) also includes within the meaning of appropriation situations where a defendant has come by the property without stealing it, but has later assumed a right to it by keeping it or dealing with it as owner. This covers situations where the defendant has picked up someone else’s property, eg a coat or a briefcase, thinking that it was his own. On getting home the defendant then realises that it is not his. If he then decides to keep the property, this is a later assumption of a right and is an appropriation for the purposes of the Theft Act 1968.

However, under s 3(1) if the person has stolen the item originally, then any later keeping or dealing is not an appropriation. This was important in Atakpu and Abrahams (1994) Crim LR 693. The defendants had hired cars in Germany and Belgium using false driving licences and passports. They were arrested at Dover and charged with theft. The Court of Appeal quashed their convictions because the moment of appropriation under the law in Gomez (1993) (see section 13.2.3) was when they obtained the cars. So the theft had occurred outside the jurisdiction of the English courts. As they had already stolen the cars, keeping and driving them could not be an appropriation. This meant that the theft was completed in the country where they hired the cars, and there was no theft in this country.

13.2.2 Consent to the appropriation

Can a defendant appropriate an item when it has been given to them by the owner? This is an area which has caused major problems. Nowhere in the Theft Act does it say that the appropriation has to be without the consent of the owner. So, what is the position where the owner has allowed the defendant to take something because the owner thought that the defendant was paying for it with a genuine cheque? Or where the item was hired (as in Atakpu and Abrahams), but unknown to the owner the defendant intended to take it permanently? This point was addressed in Lawrence (1972) AC 626; (1971) Cr App R 64.

CASE EXAMPLE

Lawrence (1972) AC 626; (1971) Cr App Rep 64

An Italian student, who spoke very little English, arrived at Victoria Station and showed an address to Lawrence who was a taxi driver. The journey should have cost 50p, but Lawrence told him it was expensive. The student got out a £1 note and offered it to the driver. Lawrence said it was not enough and so the student opened his wallet and allowed Lawrence to help himself to another £6. Lawrence put forward the argument that he had not appropriated the money, as the student had consented to him taking it. Both the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords rejected this argument and held that there was appropriation in this situation.

Viscount Dilhorne said:

JUDGMENT

‘I see no ground for concluding that the omission of the words “without the consent of the owner” was inadvertent and not deliberate, and to read the subsection as if they were included is, in my opinion, wholly unwarranted. Parliament by the omission of these words has relieved the prosecution of the burden of establishing that the taking was without the owner’s consent. That is no longer an ingredient of the offence.’

This view of Viscount Dilhorne is supported by the fact that under the old law in the Larceny Act 1916, the prosecution had to prove that the property had been taken without the consent of the owner.

However, in Morris (1983) the House of Lords did not take the same view. This was the case where the defendant had switched labels on goods in a supermarket. Lord Roskill said ‘the concept of appropriation involves not an act expressly or impliedly authorised by the owner but an act by way of adverse interference with or usurpation of [the rights of an owner]’.

In fact this part of the judgment in Morris (1983) was obiter, since the switching of the labels was clearly an unauthorised act. But the judgment in Morris (1983) caused confusion since it contradicted Lawrence without the Law Lords saying whether Lawrence (1972) was overruled or merely distinguished.

Parker LJ pointed out that in Lawrence (1972) the student had merely allowed or permitted the taxi driver to take the extra money. This was consistent with the concept of consent but differed from situations where the owner had authorised the taking as in Skipp (1975) Crim LR 114 and Fritschy (1985) Crim LR 745. In Skipp (1975), a lorry driver posing as a haulage contractor was given three loads of oranges and onions to take from London to Leicester. Before reaching the place for delivery he drove off with the loads. The Court of Appeal held that the collecting of the loads was done with the consent of the owner and that the appropriation had only happened at the moment he diverted from his authorised route.

Parker LJ considered this case in his judgment in Dobson (1990) and pointed out that at the time of loading the goods on to the lorry there was more than consent: there was express authority. The same had happened in Fritschy (1985) where D, the agent of a Dutch company dealing in coins was asked by the company to collect some krugerrands (foreign coins) from England and take them to Switzerland. He collected them and went to Switzerland but then went off with them. The Court of Appeal quashed his conviction for theft because all that he did in England was consistent with the authority given to him. There was no act of appropriation within the jurisdiction: this only occurred after Fritschy had got to Switzerland.

13.2.3 The decision in Gomez

The point as to whether the appropriation had to be without the consent of the owner was considered again by the House of Lords in Gomez (1993) 1 All ER 1.

CASE EXAMPLE

Gomez (1993) 1 All ER 1

Gomez was the assistant manager of a shop. He persuaded the manager to sell electrical goods worth over £17, 000 to an accomplice and to accept payment by two cheques, telling the manager they were as good as cash. The cheques were stolen and had no value. Gomez was charged and convicted of theft of the goods.

The Court of Appeal quashed the conviction, relying on the judgment in Morris (1983) that there had to be ‘adverse interference’ for there to be appropriation. They decided that the manager’s consent to and authorisation of the transaction meant there was no appropriation at the moment of taking the goods. The case was appealed to the House of Lords with the Court of Appeal certifying, as a point of law of general public importance, the following question:

‘When theft is alleged and that which is alleged to be stolen passes to the defendant with the consent of the owner, but that has been obtained by a false representation, has (a) an appropriation within the meaning of section 1(1) of the Theft Act 1968 taken place, or (b) must such a passing of property necessarily involve an element of adverse interference with or usurpation of some right of the owner?’

JUDGMENT

‘While it is correct to say that appropriation for purposes of section 3(1) includes the latter sort of act [adverse interference or usurpation], it does not necessarily follow that no other act can amount to an appropriation and, in particular, that no act expressly or impliedly authorised by the owner can in any circumstances do so. Indeed Lawrence v Commissioner of Metropolitan Police is a clear decision to the contrary since it laid down unequivocally that an act may be an appropriation notwithstanding that it is done with the consent of the owner.’

Lord Keith also stated that no sensible distinction could be made between consent and authorisation. Lord Browne-Wilkinson who agreed with Lord Keith put the point on consent even more clearly when he said:

JUDGMENT

‘I regard the word “appropriate” in isolation as being an objective description of the act done irrespective of the mental state of the owner or the accused. It is impossible to reconcile the decision in Lawrence (that the question of consent is irrelevant in considering whether this has been an appropriation) with the views expressed in Morris which latter views, in my judgment, were incorrect.’

This judgment in Gomez (1993) resolved the conflicts of the earlier cases as the judgment in Lawrence was approved while the dictum of Lord Roskill in Morris (1983) was disapproved. The cases of Skipp (1975) and Fritschy (1985) were overruled.

The decision widened the scope of theft but it can be argued that it is now too wide. It made s 15 of the Theft Act 1968 (obtaining property by deception — now repealed and replaced by offences under the Fraud Act 2006) virtually unnecessary as situations of obtaining by deception could be charged as theft. The facts in Gomez (1993) were clearly obtained by deception as he persuaded the manager to hand over the goods by telling him the cheques were as good as cash when he knew they were worthless.

This factor was one of the reasons for Lord Lowry dissenting from the decision of the majority in Gomez (1993). He also thought that extending the meaning of appropriation in this way was contrary to the intentions of the Criminal Law Revision Committee in their Eighth Report. Lord Lowry thought that the Law Lords should have looked at that report in deciding the meaning of appropriation. However, the majority accepted Lord Keith’s view that it served no useful purpose to do so.

It can be argued that the effect of the decision in Gomez (1993) has been to redefine theft. This point of view was put by a leading academic, Professor Sir John Smith, who wrote:

QUOTATION

‘Anyone doing anything whatever to property belonging to another, with or without his i consent, appropriates it; and, if he does so dishonestly and with intent by that, or any: subsequent act, to permanently deprive, he commits theft.’

D Ormerod, Smith and Hogan Criminal Law (13th edn, OUP, 2011), p 787

ACTIVITY

Looking at judgments

The following are two extracts from the decision in the House of Lords in the case of Gomez(1993) 1 All ER 1. The first is from the judgment of Lord Keith of Kinkel. The second is from the dissenting judgment by Lord Lowry.

Read the extracts and answer the questions on the next page.

Lord Keith of Kinkle

‘ … The actual decision in Morris was correct, but it was erroneous, in addition to being unnecessary for the decision, to indicate that an act expressly or impliedly authorised by the owner could never amount to an appropriation. There is no material distinction between the facts in Dobson and those in the present case. In each case the owner of the goods was induced by fraud to part with them to the rogue. Lawrence makes it clear that consent to or authorisation by the owner of the taking by the rogue is irrelevant. The taking amounted to an appropriation within the meaning of section 1(1) of the Theft Act …

… The decision in Lawrence was a clear decision of this House upon the construction of the word “appropriate” in section 1(1) of the Act, which had stood for twelve years when doubt was thrown upon it by obiter dicta in Morris. Lawrence must be regarded as authoritative and correct, and there is no question of it now being right to depart from it’

Lord Lowry

‘… To be guilty of theft the offender, as I shall call him, must act dishonestly and must have the intention of permanently depriving the owner of property. Section 1(3) shows that in order to interpret the word “appropriates” (and thereby to define theft), sections 1 to 6 must be read together. The ordinary and natural meaning of “appropriate” is to take for oneself, or to treat as one’s own, property which belongs to someone else. The primary dictionary meaning is “take possession of, take to oneself, especially without authority”, and that is in my opinion the meaning which the word bears in section 1(1). The act of appropriating property is a one-sided act, done without the consent or authority of the owner. And, if the owner consents to transfer property to the offender or to a third party, the offender does not appropriate the property, even if the owner’s consent has been obtained by fraud. This statement represents the old doctrine in regard to obtaining property by false pretences, to which I shall advert presently.

Coming now to section 3, the primary meaning of “assumption” is “taking on oneself”, again a unilateral act, and this meaning is consistent with subsections (1) and (2). To use the word in its secondary, neutral sense would neutralise the word “appropriation”, to which assumption is here equated, and would lead to a number of strange results. Incidentally, I can see no magic in the words “an owner” in subsection (1). Every case in real life must involve the owner or the person described in section 5(1); “the rights” may mean “all the rights”, which would be the normal grammatical meaning, or (less probably, in my opinion) “any rights”: see R. v. Morris (1984) A.C. at p. 332H. For present purposes it does not appear to matter; the word “appropriate” does not on either interpretation acquire the meaning contended for by the Crown.’

1.This decision was by the House of Lords. (Remember this was the final court of appeal at the time — the Supreme Court has since replaced the House of Lords.) What effect do judgments of the House of Lords have on courts below them in the court hierarchy?

2.In his judgment Lord Keith refers to the cases of Morris (1983) 3 All ER 288, Dobson (Dobson v General Accident and Fire Insurance Corp (1990) 1 QB 354) and Lawrence (1972) AC 626. Explain briefly the facts and decisions in these three cases.

3.According to Lord Keith, what did the case of Lawrence make clear?

4.In the penultimate sentence of the extract from Lord Keith’s judgment, he refers to obiter dicta. Explain what is meant by obiter dicta.

5.Lord Lowry gave a dissenting judgment. What is meant by a ‘dissenting judgment’?

6.What meaning did Lord Lowry state that ‘appropriates’ has?

7.Why did Lord Lowry disagree with the other judges in the House of Lords?

KEY FACTS

Key facts on appropriation

| Law on appropriation | Section/case | Comment |

| Definition is ‘any assumption of the rights of an owner’. | s 3(1) Theft Act 1968 | Includes a later assumption where D has come by the property without stealing it. |

| No need to touch property for an appropriation. | Pitham v Hehl (1977) | An offer to sell property was appropriation of the rights of the owner. |

| No need for the assumption of all of the rights of an owner. | Morris (1983) | An assumption of any of the rights is sufficient (label swapping on goods in supermarket). |

| There can be an assumption even though there is apparent consent. | Lawrence (1972) | Irrelevant whether owner consents to appropriation or not. |

| Where consent is obtained by fraud there can still be appropriation. | Gomez (1993) | An assumption of any of the rights is sufficient. No need for adverse interference with or usurpation of some right of the owner. |

| There can still be appropriation even though the owner truly consents to it. | Hinks (2000) | Appropriation is a neutral word. No differentiation between cases of consent induced by fraud and consent given in any other circumstances. All are appropriation, even gifts. |

| Where property is transferred for value to a person acting in good faith, no later assumption of rights can be theft. | s 3(2) Theft Act 1968 Wheeler (1990) | When sale is complete before the seller knows the items are stolen, the later completion of the sale when the facts are known does not make it theft. |

13.2.4 Consent without deception

So does the decision in Gomez (1993) extend to situations where a person has given property to another without any deception being made? This was the problem raised in the case of Hinks (2000) 4 All ER 833.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hinks (2000) 4 All ER 833

Hinks was a 38-year-old woman who had befriended a man who had a low IQ and was very naive. He was, however, mentally capable of understanding the concept of ownership and of making a valid gift. Over a period of about eight months Hinks accompanied the man on numerous occasions to his building society where he withdrew money. The total was about £60, 000 and this money was deposited in Hinks‘ account. The man also gave Hinks a television set. She was convicted of theft of the money and the TV set. The judge directed the jury to consider whether the man was so mentally incapable that the defendant herself realised that ordinary and decent people would regard it as dishonest to accept a gift from him.

On appeal it was argued that, if the gift was valid, the acceptance of it could not be theft. The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal and the following question was certified for the House of Lords to consider:

‘Whether the acquisition of an indefeasible title to property is capable of amounting to an appropriation of property belonging to another for the purposes of section 1(1) of the Theft Act 1968?’

In the House of Lords the appeal was dismissed on a majority of three judges to two with four of them giving the answer ‘yes’ to the question. Lord Hobhouse dissented and answered the question in the negative. Lord Hutton, although agreeing with the majority on the point of law, dissented on whether the conduct showed dishonesty.

Lord Steyn gave the leading judgment. He pointed out that in the case of Gomez (1993), the House of Lords had already made it clear that any act may be an appropriation regardless of whether it was done with or without the consent of the owner. They had also rejected a submission that there could be no appropriation where the entire proprietary interest in property passed. Lord Steyn summarised the law in Gomez (1993) as follows.

JUDGMENT

‘… it is immaterial whether the act was done with the owner’s consent or authority. It is true of course that the certified question in R v Gomez referred to the situation where consent had been obtained by fraud. But the majority judgments do not differentiate between cases of consent induced by fraud and consent given in any other circumstances. The ratio involves a proposition of general application. R v Gomez therefore gives effect to s 3(1) of the 1968 Act by treating “appropriation” as a neutral word comprehending “any assumption by a person of the rights of an owner”.’

A major argument against the ruling in Hinks (2000) is that in civil law the gift was valid and the £60, 000 and the TV set belonged to the defendant. Lord Steyn accepted that this was the situation, but he considered that this was irrelevant to the decision.

JUDGMENT

‘The purposes of the civil law and the criminal law are somewhat different. In theory the two systems should be in perfect harmony. In a practical world there will sometimes be some disharmony between the two systems. In any event it would be wrong to assume on a priori grounds that the criminal law rather than the civil law is defective. Given the jury’s conclusions, one is entitled to observe that the appellant’s conduct should constitute theft, the only charge available. The tension which exists between the civil and the criminal law is therefore not in my view a factor which justifies a departure from the law as stated in Lawrence’s case and R v Gomez.’

Lord Hobhouse dissented for three main reasons:

That the law on gifts involves conduct by the owner in transferring the gift, and once this was done, the gift was the property of the donee. It was not even necessary that the donee should know of the gift, for example, money could be transferred to the donee’s bank account without the donee’s knowledge. In view of this it was impossible to say, as the Court of Appeal had, that a gift may be clear evidence of appropriation.

That the law on gifts involves conduct by the owner in transferring the gift, and once this was done, the gift was the property of the donee. It was not even necessary that the donee should know of the gift, for example, money could be transferred to the donee’s bank account without the donee’s knowledge. In view of this it was impossible to say, as the Court of Appeal had, that a gift may be clear evidence of appropriation.

That, as a gift transfers the ownership in the goods to the donee at the moment the owner completes the transfer, the property ceased to be ‘property belonging to another’ unless it could be brought within the situations identified in s 5 of the Theft Act 1968 (see section 13.4.2).

That, as a gift transfers the ownership in the goods to the donee at the moment the owner completes the transfer, the property ceased to be ‘property belonging to another’ unless it could be brought within the situations identified in s 5 of the Theft Act 1968 (see section 13.4.2).

If the acceptance of a gift is treated as an appropriation, this creates difficulties under s 2(1)(a) of the Act which states that a person is not dishonest if he appropriated property in the belief that he had in law a right to deprive the other person of it. The donee does indeed have a right to deprive the donor of the property.

If the acceptance of a gift is treated as an appropriation, this creates difficulties under s 2(1)(a) of the Act which states that a person is not dishonest if he appropriated property in the belief that he had in law a right to deprive the other person of it. The donee does indeed have a right to deprive the donor of the property.

He also pointed out that there were further difficulties under the Theft Act 1968 as under s 6 (which defines intention to permanently deprive — see section 13.6) the donee would not be acting regardless of the donor’s rights as the donor has already surrendered his rights. Further it was difficult to say that under s 3 the donee was ‘assuming the rights of an owner’ when she already had those rights under the law on gifts.

Despite these arguments put forward by Lord Hobhouse, the majority ruling means that even where there is a valid gift the defendant is considered to have appropriated the property. The critical question is whether what the defendant did was dishonest.

13.2.5 Appropriation of credit balances

Another area which has created difficulty for the courts is deciding when appropriation takes place where the object of the theft is a credit balance in a bank or building society account. In such cases the thief may be in a different place (or even country) to the account. In Tomsett (1985) Crim LR 369, $7m was being transferred by one bank to another in New York in order to earn overnight interest. The defendant, an employee of the first bank in London, sent a telex diverting the $7m plus interest to another bank in New York for the benefit of an account in Geneva. The Court of Appeal accepted, without hearing any argument on the point, that the theft could only occur where the property was. This meant that D was not guilty of theft under English law, as the theft was either in New York or Geneva. The money had never been in an account in England. So even though D’s act occurred in London, the matter was outside the jurisdiction of the English courts.

This does not seem a very satisfactory decision, and in fact it was not followed by the Divisional Court in Governor of Pentonville Prison, ex parte Osman (1989) 3 All ER 701 when deciding whether Osman could be deported to stand trial for theft in Hong Kong. Osman had sent a telex from Hong Kong to a bank in New York instructing payment from one company’s account to another company’s account. If Tomsett (1985) had been followed, then the theft would have been deemed to have occurred in New York. However, the Divisional Court held that the sending of the telex was itself the appropriation, and so the theft took place in Hong Kong.

JUDGMENT

‘In R v Morris … the House of Lords made it clear that it is not necessary for an appropriation that the defendant assume all rights of an owner. It is enough that he should assume any of the owner’s rights … If so, then one of the plainest rights possessed by the owner of the chose in action in the present case must surely have been the right to draw on the account in question … So far as the customer is concerned, he has a right as against the bank to have his cheques met. It is that right which the defendant assumes by presenting a cheque, or by sending a telex instruction without authority. The act of sending the telex instruction is therefore the act of theft itself.’

The most surprising point about this decision is that two of the judges (Lloyd LJ and French J) had also decided the case of Tomsett (1985) but then refused to follow their own decision.

In the judgment in Osman (1989) the court had mentioned presenting a cheque as one of the rights of an owner, and this was the situation which occurred in Ngan (1998) 1 Cr App Rep 331.

CASE EXAMPLE

Ngan (1998) 1 Cr App Rep 331

D had opened a bank account in England and been given an account number which had previously belonged to a debt collection agency. Over £77, 000 intended for the agency was then paid into D’s bank account. Because of s 5(4) of the Theft Act 1968 (see section 13.4.4) this money was regarded as belonging to the agency. D realised there was a mistake but signed and sent blank cheques to her sister (who also knew of the circumstances) in Scotland. Two cheques were presented in Scotland and one in England.

The Court of Appeal applied the principle in Osman (1989) that the presentation of a cheque was the point at which the assumption of a right of the owner took place. They quashed D’s conviction for theft in respect of the two cheques presented in Scotland, as they were outside the jurisdiction of the English courts, but upheld her conviction for theft in respect of the cheque presented in England. They took the view that signing blank cheques and sending them to her sister were preparatory acts to the theft and not the actual theft.

However, it should be noted that in Osman (1989) the court had also stated that appropriation took place when the defendant dishonestly issued a cheque. So, it could be argued that the decision in Ngan was wrong as sending the cheques to her sister was ‘issuing’ them.

The problems of when and where appropriation takes place in banking cases has become even more difficult with the use of computer banking. In Governor of Brixton Prison, ex parte Levin (1997) 3 All ER 289, the Divisional Court distinguished the use of a computer from the sending of a telex or the presentation of a cheque. D had used a computer in St Petersburg, Russia to gain unauthorised access to a bank in Parsipenny, America and divert money into false accounts. The court ruled that appropriation took place where the effect of the keyboard instructions took place.

JUDGMENT

‘We see no reason why the appropriation of the client’s right to give instructions should not be regarded as having taken place in the computer [in America]. Lloyd LJ [in Osman] did not rule out the possibility of the place where the telex was received also being counted as the place where the appropriation occurred if the courts ever adopted the view that a crime could have a dual location … [T]he operation of the keyboard by a computer operator produces a virtually instantaneous result on the magnetic disc of the computer even though it may be 10, 000 miles away. It seems to us artificial to regard the act as having been done in one rather than the other place. But, in the position of having to choose … we would opt for Parsipenny. The fact that the applicant was physically in St Petersburg is of far less significance than the fact that he was looking at and operating on magnetic discs located in Parsipenny. The essence of what he was doing was there. Until the instruction is recorded on the disc there is in fact no appropriation.’

These cases leave the law on where and when appropriation takes places in banking cases a little uncertain, but the principles appear to be:

telex instructions — appropriation at place and point of sending telex

telex instructions — appropriation at place and point of sending telex

presenting a cheque — appropriation at place and point of presentation

presenting a cheque — appropriation at place and point of presentation