THE RULE OF LAW AND A SEPARATION OF POWERS

2

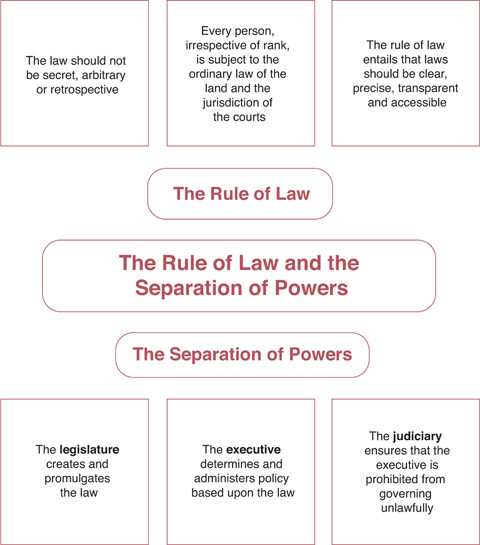

The rule of law and a separation of powers

2.1 A description of the rule of law

2.1.1 The rule of law is capable of many definitions, based on both philosophical and political theories, and hence it is a difficult doctrine to explain definitively.

2.1.3 Carroll defines the rule of law as ‘neither a rule nor a law’. It is now generally understood as a doctrine of political morality which concentrates on the role of law in securing the correct balance of rights and powers between individuals and the State in free and civilised societies.

2.1.4 The rule of law can be interpreted as:

- • an overarching, universal law that applies to everyone, including the executive and legislature; and

- • that man-made laws should conform to a ‘higher’ law, the rule of law.

2.1.5 The rule of law is consequently often recognised as a means of ensuring the protection of individual rights against governmental power.

2.2 Dicey’s formulation of the rule of law

2.2.1 In the United Kingdom, the general concept of the rule of law has become identified with Dicey’s explanation of the doctrine in his 1885 text, An Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution. According to Dicey, the rule of law was a distinct feature of the UK constitution, with three main concepts.

2.2.2 Firstly: No person is punishable in body or goods except for a distinct breach of the law (Entick v Carrington (1765)). This concept attempts to ensure that law is not secret, arbitrary or retrospective, thereby limiting the discretionary power of Government. To comply with the rule of law, laws should be clear, precise, transparent and accessible.

2.2.3 Secondly: Every person, irrespective of rank, is subject to the ordinary law of the land and the jurisdiction of the courts. Dicey based this principle on the UK system as compared with those of the time in, for example, France, where disputes with Government officials were heard in administrative courts separate from the ordinary civil courts and where different rules applied.

2.2.4 Thirdly: The common law creates a system of rights and liberties superior to that offered by any declaration or Bill of Rights. This is because the common law system emphasises remedies for infringement of rights rather than merely declaring the content of those rights.

2.3 Bingham’s view of the rule of law

2.3.1 Much more recently than Dicey’s ideas, there has been a highly regarded dissection of the concept of the rule of law, as proffered by Sir Tom Bingham, a much-loved former Law Lord, in his text The Rule of Law (2010).

2.3.2 In this book, Bingham offered up his own useful, working definition of the rule of law:

‘All persons and authorities within the state, whether public or private, should be bound by and entitled to the benefit of laws publicly made, taking effect (generally) in the future and publicly administered by the courts.’

2.3.3 Bingham also condensed his view of the scholarship on the rule of law into eight vital principles. These serve as a sound checklist to consider before we move on to consider the extent of the operation of the rule of law in the United Kingdom today:

- (1) The law must be accessible and so far as possible intelligent, clear and predictable.

- (2) Questions of legal right and liability should ordinarily be resolved by the application of the law and not the exercise of discretion.

- (3) The laws of the land should apply equally to all, save to the extent that objective differences justify differentiation.

- (4) Ministers and public officials at all levels must exercise the powers conferred on them in good faith, fairly, for the purpose for which the powers were conferred, without exceeding the limits of such powers and not unreasonably.

- (5) The law must afford adequate protection of fundamental human rights.

- (6) Means must be provided for resolving, without prohibitive cost or inadequate delay, bona fide civil disputes which the parties themselves are unable to resolve.

- (7) Adjudicative procedures provided by the State should be fair.

- (8) The rule of law requires compliance by the State with its obligations in international war as in national law.

2.4 Examples of the rule of law as a functional element of the UK constitution

2.4.1 The existence of administrative law, particularly the process of judicial review, enables the courts to ensure power is controlled and the executive is accountable for its actions and is based on the need to ensure the rule of law.

2.4.2 Some examples of cases where the courts have referred to the significance of the doctrine in the constitution include:

- • Francome and Another v Mirror Group Newspapers Ltd and Others (1984) – where Lord Donaldson referred to the doctrine as one underpinning parliamentary democracy and extending to all citizens;

- • Merkur Island Shipping Corporation v Laughton and Others (1983) – where Lord Diplock commented on the need for the law to have clarity;

- • R v Home Secretary, ex parte Venables (1997) – the Home Secretary had considered a campaign conducted in a national newspaper when determining the sentencing of convicted children, rather than basing the decision on their progress/rehabilitation in detention. The action was considered ‘an abdication of the rule of law’;

- • R v Horseferry Road Magistrates’ Court, ex parte Bennett (1994) – where Lord Griffiths noted that it is the responsibility of the courts to maintain the rule of law, to oversee executive action and to not permit action that threatens basic human rights or breaches the rule of law;

- • M v Home Office (1994) – where, applying Dicey’s second proposition that every person is subject to the law, the House of Lords held that the Home Secretary could be found in contempt of court by disobeying an injunction; and

- • A v Secretary of State for the Home Department (2004) – where the House of Lords held that power to detain only foreign nationals indefinitely as suspected terrorists, without charge, under the Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 was a breach of both the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the rule of law.

2.5 Reconciling a strict view of the rule of law with some legal rules in the United Kingdom today

2.5.1 If we apply Dicey’s concept of the rule of law to the modern UK constitution, we can make a number of observations.

2.5.2 The first concept, that no person may have their body or goods interfered with except for a distinct breach of the law, is in direct contrast to the provisions of some present-day statutes. For example:

- • the police have powers of arrest, stop and search when they have only ‘reasonable grounds’ for suspecting certain facts in relation to a criminal offence, under the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984;

- • the Government also has power to interfere with a person’s goods/property without any breach of the law, for example, the exercise of compulsory purchase orders when buying land for development and building infrastructure like roads and railways.

2.5.3 The second concept formulated by Dicey was that no person is above the law. However, there are a number of contraventions of this principle in the modern constitution. For example:

- • the Monarch in her personal capacity is not subject to the jurisdiction of the ordinary courts;

- • the Crown is also in a privileged position in litigation (Crown Proceedings Act 1947) and cannot be sued in tort for the actions of its servants;

- • no civil action may be brought in respect of the comments or actions of a judge exercising his or her judicial role (Anderson v Gorrie (1895)) or in relation to a jury’s verdict (Bushell’s Case (1670));

- • Members of Parliament have rights and immunities beyond those granted to the ordinary citizen, such as freedom of expression and freedom from arrest in certain circumstances. Conversely, there are individuals who are subject to additional legal restraints. For example, under the Armed Forces Act 2006, members of the armed forces are subject to additional legal codes of conduct and offences, such as desertion, and a different judicial system.

2.5.4 The third concept, that common law provides protection of individual rights in the UK constitution, remains the case today, although added protection has been provided by virtue of the Human Rights Act 1998, for example.

2.5.5 The faith Dicey had in the ability of the common law to protect rights and liberties, though, has been criticised.

- • Dicey failed to appreciate that the effectiveness of the common law in offering such protection can be greatly reduced by the pre-eminence given to statute, a consequence of the supremacy of Parliament.

- • Hence, while the common law may offer protection in the form of remedies for those whose rights are infringed, statute may remove that protection, as was the case in Burmah Oil v Lord Advocate (1965).

2.5.6 Here are some examples of specific criticisms of Dicey’s view of the rule of law:

- • Sir Ivor Jennings claimed that Dicey’s standard of the rule of law was influenced by his political views and that the phrase could be used to describe any society where a state of law and order exists.

- • Consequently, the rule of law is seen to operate ‘best’ in societies that meet Dicey’s standards. Jennings instead claimed that the rule of law may exist in societies that do not meet Dicey’s standards – in other words, that the rule of law can exist in political systems other than those based on traditional Western democratic models.

2.6 Some broader interpretations of what the ‘rule of law’ might entail

The rule of law as a political concept

2.6.1 Laws should exhibit particular characteristics and meet minimum standards in terms of the way they are expressed and administered. For example, Raz argues that the making of laws should be guided by the following principles:

However, Raz’s approach has been criticised as placing too much emphasis on procedure as a means of protecting rights, whilst failing actually to identify the nature and extent of the rights themselves.